This article was published in issue #7889 of British Journal of Photography. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.

Of all the metals present on Earth, gold has a particularly compelling story. It is said to be created, as indeed they all are, in supernova nucleosynthesis, or during the dying of a star, when it is one of the very last elements to form. It is then ricocheted into our universe in the form of asteroids and meteors, which rained down on our planet long ago, planting its reserves deep beneath its surface. Though gold is not scarce in the universe, it is very scarce on Earth; we’ve excavated only three Olympic-sized swimming pools’ worth so far. And it is all the more precious for it.

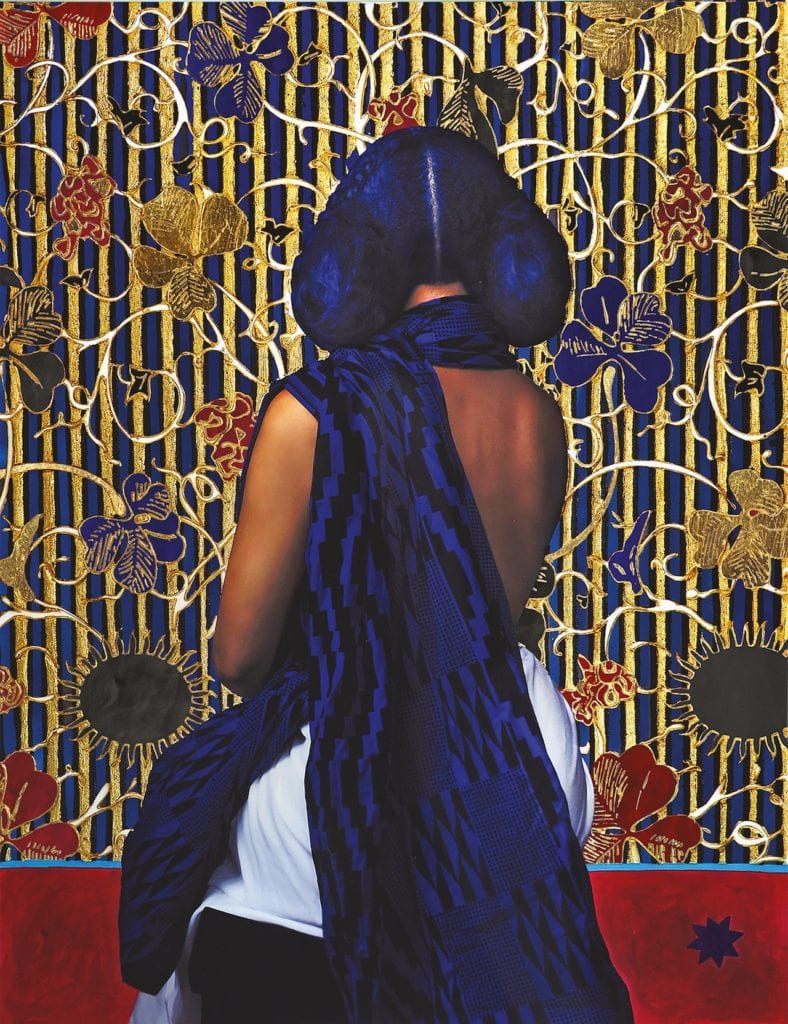

“That, to me, is a glorious story!” exclaims British-Liberian artist Lina Iris Viktor over the phone from her studio in New York, after telling it. Her own practice weaves photography, painting and installation with plenty of gold: since 2014, gleaming 24-carat veins have run across her work, delineating ancient symbols or picking out the profile of her protagonist. As a result, Viktor’s pieces are almost celestial in the way they seem to gather up all the light in a room. “There’s an emotional reaction that happens when people are in the presence of pure gold,” she continues. “Human beings have had this storied history with it ever since we found out it existed. Ancient civilisations had such a reverence for it that they likened it to the sun on Earth. It was godly. It wasn’t a material of this planet. To be in the presence of it wasn’t monetary, but a spiritual wealth, a conduit between worlds. You look at the most religious spaces on the planet – the cathedrals, mosques and temples – and they’re all gilded.”

But in Viktor’s work, gold’s contemporary future resonates just as powerfully as its astrophysical origin. Her practice looks often, for example, at the African diaspora, and studies blackness in its many multifaceted forms. That the African continent has been torn apart by people in the pursuit of power and resources – among them, gold – is not lost on the artist. “In Western society in this last couple of hundred years, we’ve lost our reverence for gold,” she says. “There’s something far more to glean from this metal than just bullions in some reserve somewhere that tell a country its wealth.” By placing this treasured material within a limited colour palette – next to cobalt blue, rich red and deep, dark hues – and using it to investigate universal truths, Viktor hopes to return it, if only momentarily, to its elementary state.

This autumn, she will do so before a British audience. A new exhibition of Viktor’s work – existing, and newly commissioned for the show – opens at Autograph ABP, curated by Renée Mussai. Entitled Some Are Born to Endless Night – Dark Matter, it is the artist’s first major solo exhibition in the UK, and, spanning photography, painting and sculptural installation, perhaps her most expansive output yet.

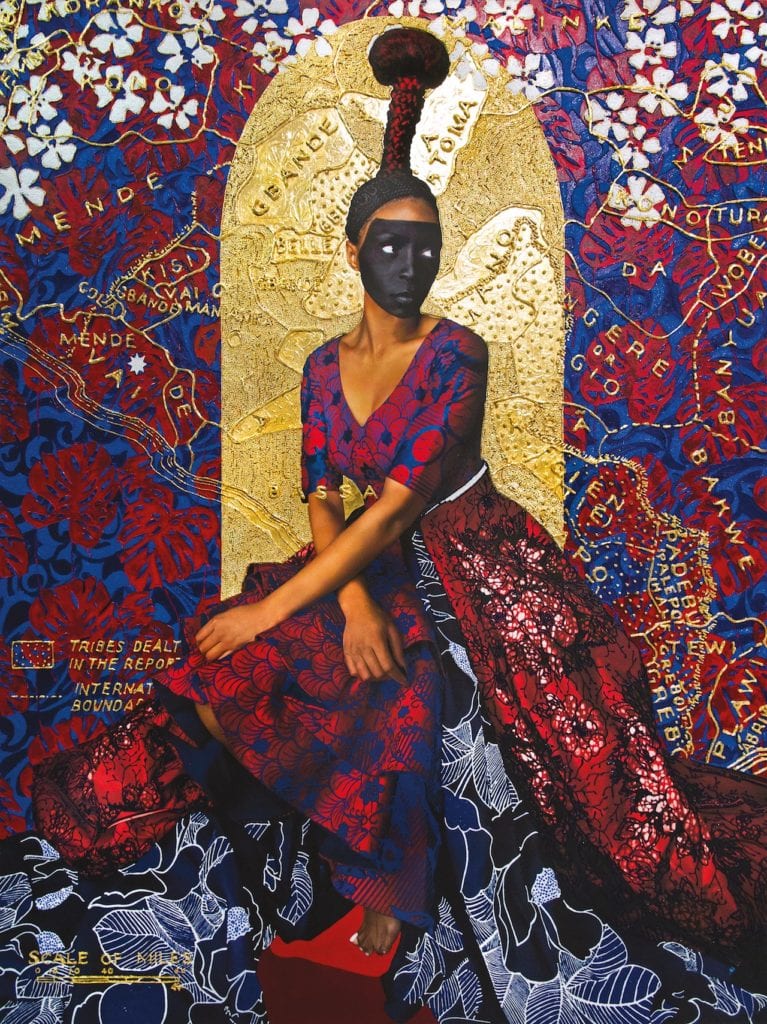

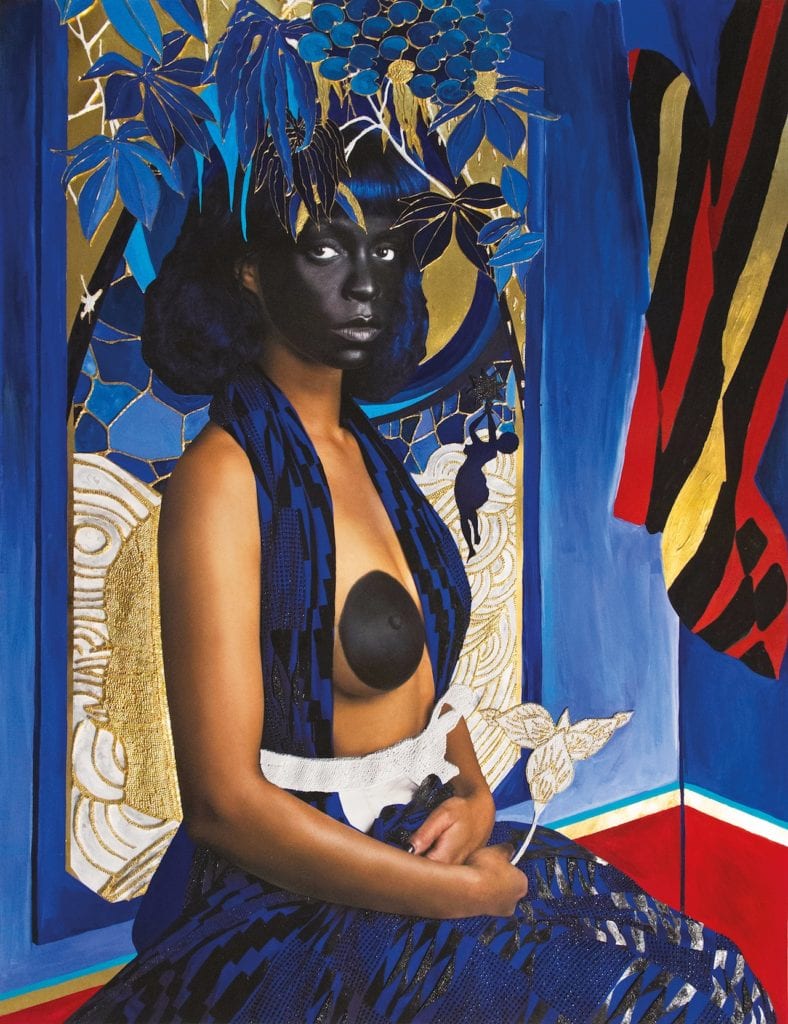

DARK CONTINENT XIII XXIV THE FALL, Courtesy of the artist and Mariane Ibrahim Gallery © Lina Iris Viktor.

Gold, of course, features heavily. But Viktor’s practice is innately multidisciplinary. She was educated at an international school in London, where her primary focus was on the performing arts. As a seven-day boarder, she explains, “you grow up in this whirlpool of multiple cultures and religions, and learning different languages, and living with people from all over the world. It gave me the worldview I have today.” She went on to study theatre at Sarah Lawrence College in the US, but found the experience profoundly reductive. “America was a huge culture shock for me,” she says.

The racial and sociopolitical frustrations she experienced there precipitated a change of direction. “I was like, this is not going to be my battle for the rest of my life – trying to prove that I’m not just a ‘black woman actor’, and can only play stereotypical ‘black woman roles’.”

After a stint in film – she worked under Spike Lee for “a glorious 10 months” – Viktor opened her own design agency, but the pursuit of pure creation, or the unbridled satisfaction of making work autonomously, drew her to the artist’s studio instead. She studied photography and design, respectively, at the School of Visual Arts in New York, and set about putting her own ideas down on canvas.

“Art just happened,” she says. “The art I do now is an amalgamation of all these different disciplines I’ve learned, plus all my other interests – in astrophysics and the sciences, and math.” In fact, her circuitous route not only informed her visual language, but created space for it. “I came into this not knowing anything about how, for lack of a better term, the ‘art world’ operates. I think that naivety was good, because had I gone through traditional channels, that would stymie what I believed I could do. I didn’t know the rules, so I didn’t know there were any rules to break.”

Viktor’s practice is founded on research. She draws on art, architecture, science, maths, astrophysics, and many other influences – a broad pool, rooted in an expansive library – to deal with both the cultural histories of the global African diaspora, but also ancient civilisations from across time and space. Though symbols and rich material legacies are often interwoven with her own image (photographed, and then printed on the canvas, before being painted and sculpted upon) to create complex and cohesive narratives, she is quick to elucidate that these are not self-portraits. “I think the purpose of a self-portrait is to reveal aspects that are hidden to yourself, or your viewer, to dig into aspects of your own character. But that’s not the purpose of my work at all,” she says. Rather, “it’s almost like the body becomes a universal form”.

That form might be a specific character – Yaa Asantewaa, an Ashanti warrior queen, for example, or the Libyan Sibyl, a prophetess in Greek mythology who was recast, during the abolition of slavery, as a potent symbol of emancipation. In Viktor’s 2018 exhibition, A Haven. A Hell. A Dream Deferred, she interrogated the cultural heritage of this latter figure in a broader exploration of the connection between Liberia, her parents’ native country, and New Orleans, where the exhibition took place. Working with characters in this way lends these pieces a performative element, she says. She allows her viewer to step into a universe she has created. “That’s why the works are performative to me,” she says, “because I’ll take on different characters.”

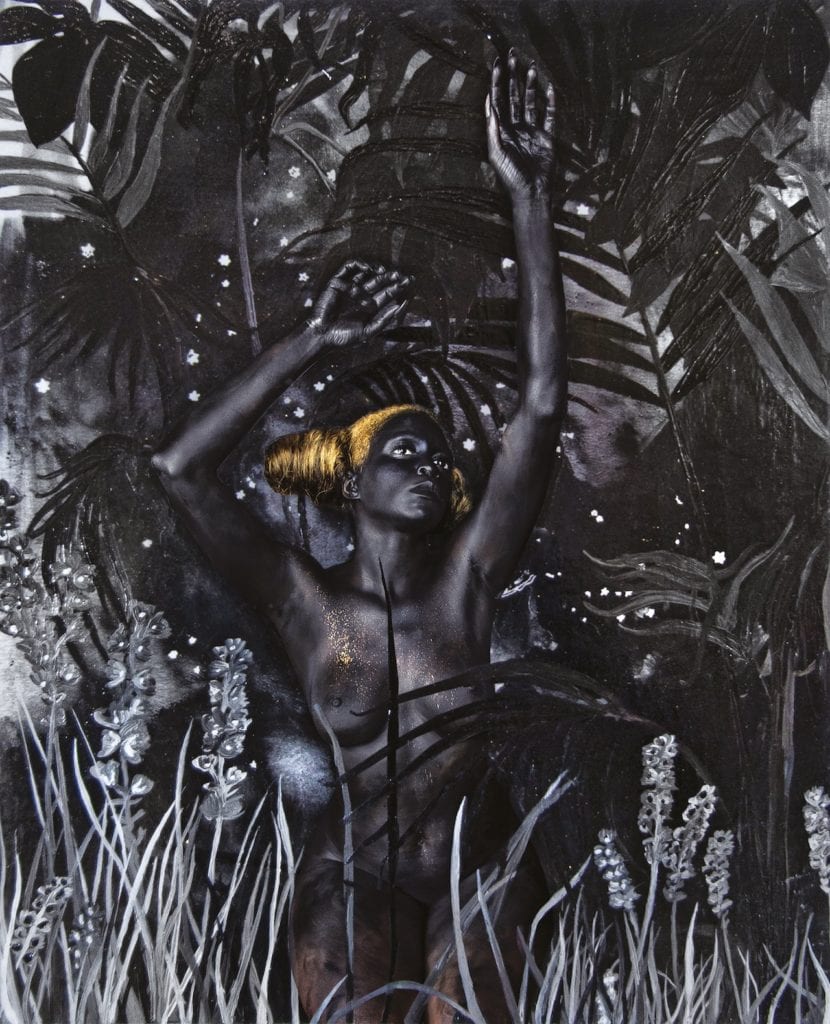

Other concepts are more organic and intuitive, however, and see her assume the form of a universal body which is, crucially, neither male nor female. “I think we each have the masculine and the feminine gender principle,” she explains. “Although in many ways the work is supremely feminine, I feel there is something very masculine in its ownership, or in its taking-up of space. It’s more aggressive.”

And these works are aggressive – but not in any usual way. They are steeped in cultural history, and complex mathematic and scientific concepts that academics spend their entire careers learning to concisely explain. And yet, they seem to demand a kind of submission from their viewer. If you’ll just allow any pretext to fall to the floor, the artist seems to propose, you’ll feel the message for yourself. “I think that as an artist, my job is not just to digest and then vomit up information, but to synthesise that information,” Viktor says. Take, for example, the use of symbols, shapes and patterns that predate language, she continues – these can be a powerful vocabulary with which to communicate ideas about the sheer vastness of the universe, and our minute part within it.

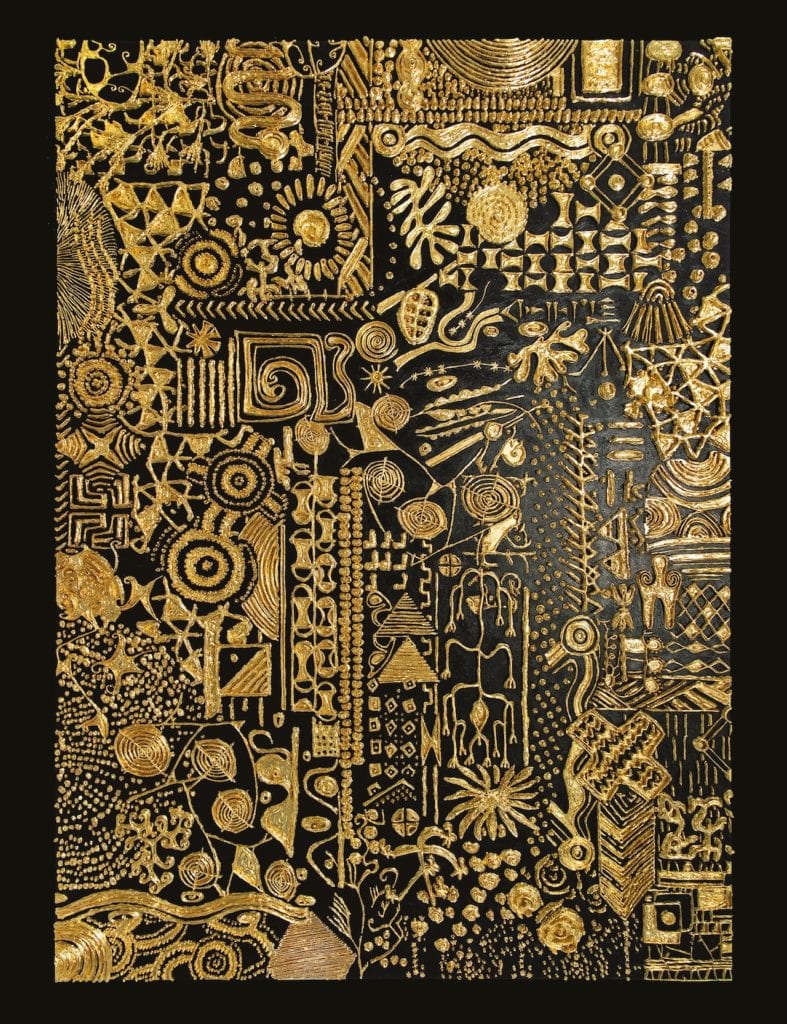

In a series such as Constellations, which takes a rich volume of ancient patterns and transposes them, in 24-carat gold, onto a black canvas, this idea is self-evident. “Patterns govern everything. We all are familiar, even if not consciously so, with patterns, because we are pattern-based – it’s in our DNA,” Viktor says. “Everything in our body is built on cycles. I liken people seeing these works to seeing things that are subliminally in their consciousness, that they don’t even know about. It has a sensation of familiarity.”

It’s true that, looking at these decadent, elementary works – painstakingly created by hand over long periods of time, and using traditional artisanal methods along with modern technology – there’s a sense of recognition. “Even though they’re not linear or literal, and you can’t take something very particular from them, I think the feeling and sensation you get from symbolic languages is far more evocative. They are everything that we are. Patterns are the closest approximation that we have, as human beings, to visually represent our place here.” In a contemporary culture which values evidence, precision and specificity above all else, there’s a profound power in relinquishing that control to a higher plane.

Lina Iris Viktor‘s Some Are Born to Endless Night – Dark Matter is on show at Autographin London until 25 January 2019