In September 2017, Ivor Prickett met Nadhira Aziz, sat in a plastic chair 15 feet from where an excavator was digging through the ruins of her home in Mosul, Iraq. “At times, she was engulfed in dust as the driver dumped mounds of stone and parts of her house beside her,” Prickett writes in his remarkable new book, End of the Caliphate, published by Steidl. “But she refused to move.” He stayed there with her, until eventually they found the remains of two women – Mrs Aziz’s sister and niece, who had been killed by an airstrike that hit the home in June, three months prior.

As the excavator continued working, Mrs Aziz occasionally shouted at the cluster of Iraqi Civil Defence workers. Her old personal possessions – books, clothes and bags – would reveal themselves from amidst the debris, and she demanded they be salvaged. “By the end of the day, she was surrounded by a pile of tattered belongings,” Prickett writes, recalling Mrs Aziz’s refusal to leave her home until the workers agreed to carry what remained of her belongings back to her makeshift home. “Watching Mrs Aziz sit amidst the dust that day was one of the most heartbreaking and inspiring things I have ever seen.” Mrs Aziz, he adds, tells us so much about the futility of war and the failure of intervention in Iraq. Nevertheless, Prickett considers the images of her, published in End of the Caliphate, as “a testament to the depth of strength” of the people that have survived two decades of continuous and unthinkably violent conflict.

The war against Isis has cost the Western alliance more than a billion dollars. It sparked an international refugee crisis that has wrought huge political change in Europe, destroyed vast tracts of the region’s ancient heritage sites, and resulted in thousands of unknown deaths – as well as inspiring Isis, the terrorist group, to turn its attention to indiscriminate attacks in the cities of Europe and America.

Prickett does not come from a starry journalistic background. Indeed, until he started reporting from Mosul for The New York Times, he had travelled under the radar while other lesser names in his field were garlanded at the assorted photojournalism awards. Prickett grew up in County Cork, and later County Meath, in the Republic of Ireland, before studying in Newport (now the University of South Wales) on the famed documentary photography course.

In 2009, after early projects focusing on stories of displaced people throughout the Balkans and Caucasus, Prickett moved to the Middle East to document the beginnings of the Arab Spring uprisings in Egypt and Libya. Initially based in Beirut, and with new representation from Panos Pictures, he decided to remain in the region, and commission by commission, came under the aegis of The New York Times.

He arrived in Iraq in 2016, just after the Iraqi government forces, backed by the Kurdish Regional Government and international forces led by the US, launched a military operation to regain Mosul from Isis in late October. By the start of 2017, the 36-year-old Irish photographer was reporting exclusively for The New York Times, enabling the famous newspaper to document the humanitarian crisis created by the war. “I found myself probing further into the city on military embeds with Iraqi forces as they battled for control of the eastern side of the city,” Prickett writes.

“It was as if, for a moment, this child made these men forget the lives they had taken and the friends they had lost over the past eight months – or, maybe, he made them remember”

Ivor Prickett

While reporting from war zones, it is the standard operating procedure for Western journalists to stick together – particularly when the enemy does not differentiate between a Western combatant and a reporter. At the time that Prickett was in Mosul, it was only a short while after some of his photojournalistic compatriots, most notably James Foley and Steven Sotloff, had been beheaded by Isis in nearby Syria – the video of their death posted on YouTube. The city was full of Isis militants, and as the fight drew on, the photographer increasingly found himself to be the only Western journalist on the ground in parts of Mosul. Access to the frontline was severely restricted but, with the help of his New York-based editor David Furst, and of TNYT’s local bureau manager in Baghdad, Falih Hassan, Prickett consistently found a way to get in. What’s more, he was able to operate without a lot of oversight, allowing him to gain a foothold on events without his shots being dictated by the officials of one side of the conflict.

The images were published under the title The Battle for Mosul, released in condensed series and accompanied by stories in The New York Times every couple of months in 2017. Prickett was suddenly talked of as one of the leading war photographers in the world, and industry recognition followed. In 2018, he won a World Press Photo Award out of two images of his that were nominated. One of these is an image [left] that may go down in the annals of war photography, and one that lies at the heart of what the work is ultimately about.

In July 2017, a young boy was carried by a man from the last Isis- controlled area in the Old City. The Iraqi Special Forces suspected the man to be an Isis militant attempting to use the boy as a shield for his own survival. After the man was taken off for questioning, the Special Forces carefully took off the boy’s tattered clothes, and began to wash his body. “It was as if, for a moment, this child made these men forget the lives they had taken and the friends they had lost over the past eight months,” says Prickett. “Or, maybe, he made them remember.”

Despite the fact the image was published by media across the world, the boy remains unidentified. And, despite his best efforts, Prickett has not yet been able to track him down, or learn of his whereabouts, so he might be able to continue to tell his story. Upon winning the award, Prickett said: “It’s in the middle of conflict, you can tell it is in a war zone, but the men have put down their weapons to care for this boy – and the frailty of his body are these very innocent indicators or symbols of the toll that war has on civilians.”

For good reason, the fighters of Isis have been depicted as almost wholly evil by the Western media. But somehow, Prickett’s photography succeeds in avoiding judgement. He recalls the final days of the fight in July 2017, in the most ancient quarter of the city, a squad of Special Forces finding an injured and emaciated Isis combatant in the basement of a ruined building. The man was dragged out on the edge of death, his ribs protruding from his body, his bearded face caked with dust. But Prickett was able to glean some details from him: he was 36, the same age as Prickett, and his name was Malik. The Special Forces attempted to stop the photographer from taking pictures, but Prickett succeeded in firing off a few shots.

“They were probably the last moments of Malik’s life,” Prickett says. “Most Isis fighters who were captured alive at that stage in the conflict were killed on the spot.” Prickett remembers this as a “surreal moment”, realising he felt empathy for a man who had knowingly contributed to the nationwide destruction, rape, pillage and murder witnessed over the previous eight months. “I couldn’t quite reconcile this,” he says. “I couldn’t understand why I thought it was important for me to take these pictures. In hindsight, I think it is because I knew this wasn’t the answer.” Prickett sees the image, and the photobook as a whole, as an active call for pacifism. “I knew that more killing didn’t bring an end to anything, but rather the wholesale destruction of Mosul’s Old City and the deaths of thousands of people who were cornered there would just seed a new generation of revenge.”

The same year that Prickett won the World Press Photo Award, he was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography. Not long after, he pitched the work to Gerhard Steidl, who packaged it into the photobook we now see. Alongside its release, the work will be exhibited at Visa pour l’image festival in Perpignan, France, later this month, and at Side Gallery in Newcastle, UK, this September.

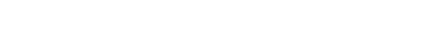

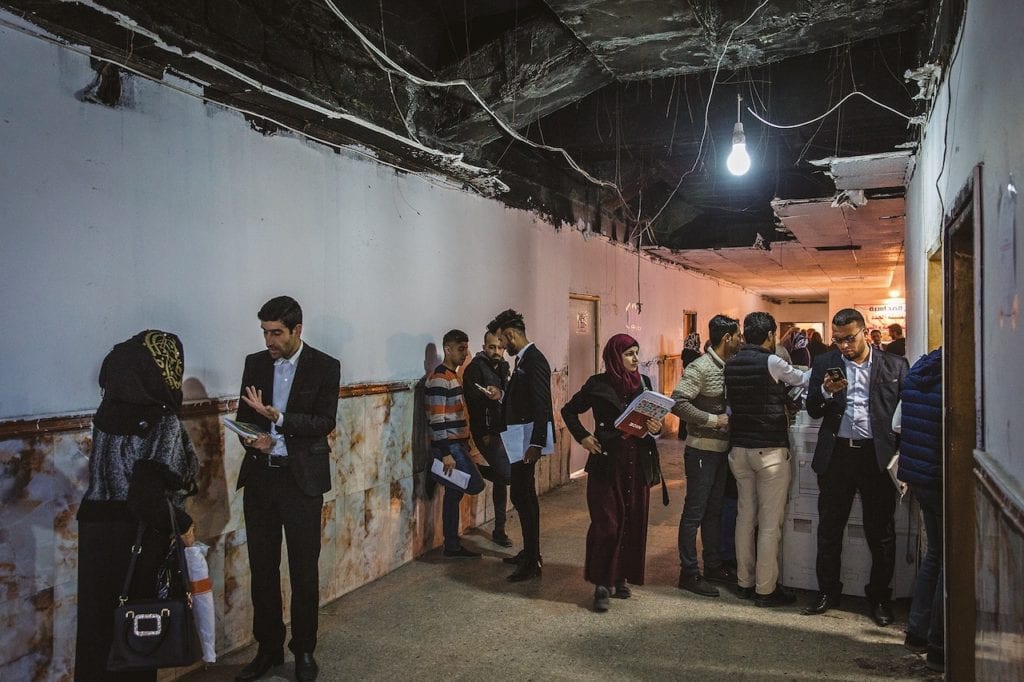

As the last of the Isis loyalists were finally defeated in some of the most intense urban warfare witnessed since the Second World War, Prickett remained to document the slow return of life from the rubble that was once a city. In May 2018, he sat in a bar in Mosul, on the banks of the Tigris, photographing people drinking and laughing. “It was hard to imagine what had happened a year before,” he says. There he was at the University of Mosul, which was heavily damaged during the fight against Isis.

Prickett captured the wild celebrations of the first students to graduate since the war’s end. In that sense, the photobook is split into two chapters – the first detailing the two years he spent on the frontlines of the war against Isis, followed by the images he’s taken in the time since, as the green shoots of recovery began to emerge amongst a civilian population who, like Nadhira Aziz, were returning to their homes and beginning to rebuild their lives from the ground up.

Prickett speaks of “listening to his fear” in a war zone, understanding that feeling afraid is normal. The challenge, he says, is to overcome the fear enough to work clearly – to not be paralysed by it, but not take risks that endanger his life. He is motivated, he says, by the importance of showing the people who have somehow outlived the era of Isis – normal citizens who have, through no fault of their own, been thrust into hell. Whatever internal mechanisms Prickett is able to employ, he has demonstrated, with End of the Caliphate, a once-in-a-generation document of one of the defining chapters of this century.

–

End of the Caliphate is published by Steidl Books. The project goes on show at at Visa pour l’image festival in Perpignan, France, from 31 August to 15 September, and Side Gallery in Newcastle, UK, from 28 September to 15 December.

This article was originally published in issue #7887 of British Journal of Photography magazine. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.