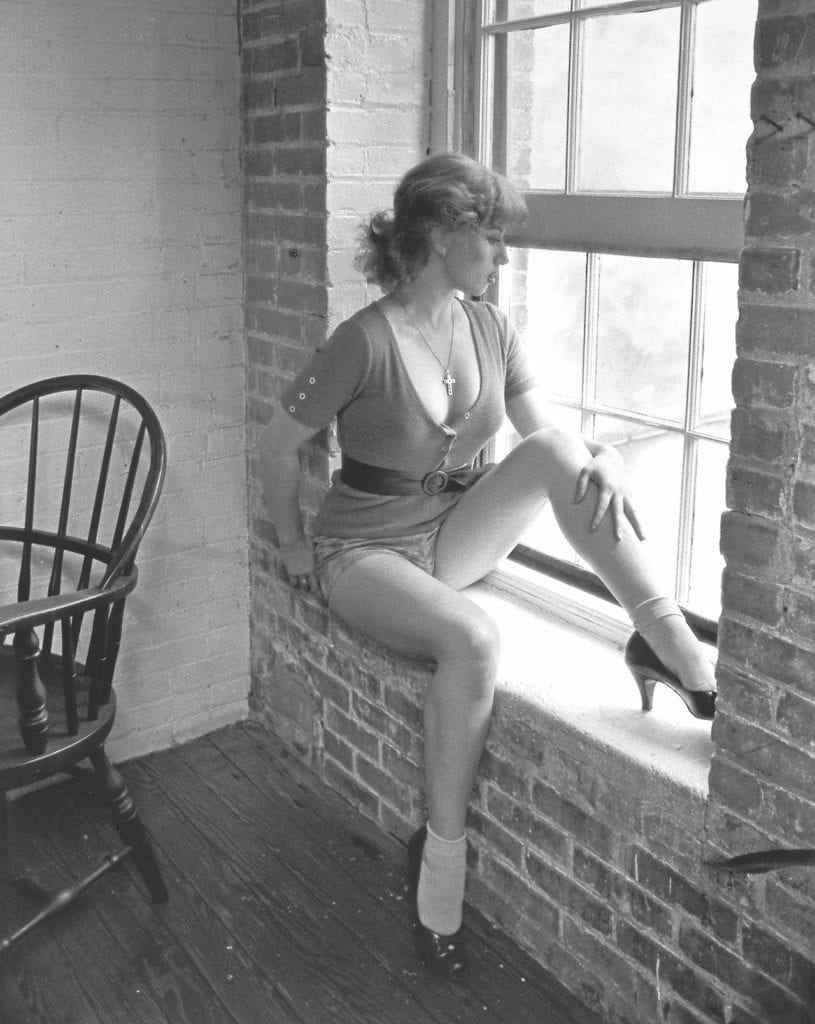

The subject and object of her own artwork, renowned American artist Cindy Sherman first gained recognition on the New York art scene with the series Untitled Film Stills, 1977-80. These small, black-and-white photographs comprise Sherman depicting herself in a variety of guises; a cast of characters who reflexively inhabit the lives of the lonely housewife, tourist, sex kitten, city girl, dancer, actress, vamp or forlorn lover. Presented as if used to promote (non-existent) film-noir movies, Sherman stage-manages and directs her own theatre of images to examine a lexicon of female stereotypes.

As Craig Owens pointed out in his 1980 essay, The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism, published in Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power and Culture (1992), “Sherman’s women are not women but images of women, spectacular models of femininity projected by the media to encourage imitation, identification; they are, in other words, tropes, figures.” Her mini-performances in public and private spaces are such that the settings, body language and facial expressions are indeterminate, and a sense of ambiguity is heightened. They possess a charge and confrontational mood akin to a Vito Acconci performance piece – vertiginous and disorienting.

Now the entire 70 images from the series go on display for the first time in the UK as part of a major retrospective curated by Paul Moorhouse at the National Portrait Gallery in London from 27 June to 15 September. Bringing together 180 works spanning 40 years, from the mid-1970s to the present day, the exhibition marks various shifts and evolution within Sherman’s practice.

Her other early works can also be seen, namely all five pieces from the Cover Girl series, created in 1976 during her student years, offering insight and expansion into Sherman as a precocious talent from the outset of her career. The triptychs repurpose original magazine covers from the likes of Vogue or Mademoiselle, followed by mock- ups of the artist enacting the model’s pose, though routinely off-kilter by way of caricature.

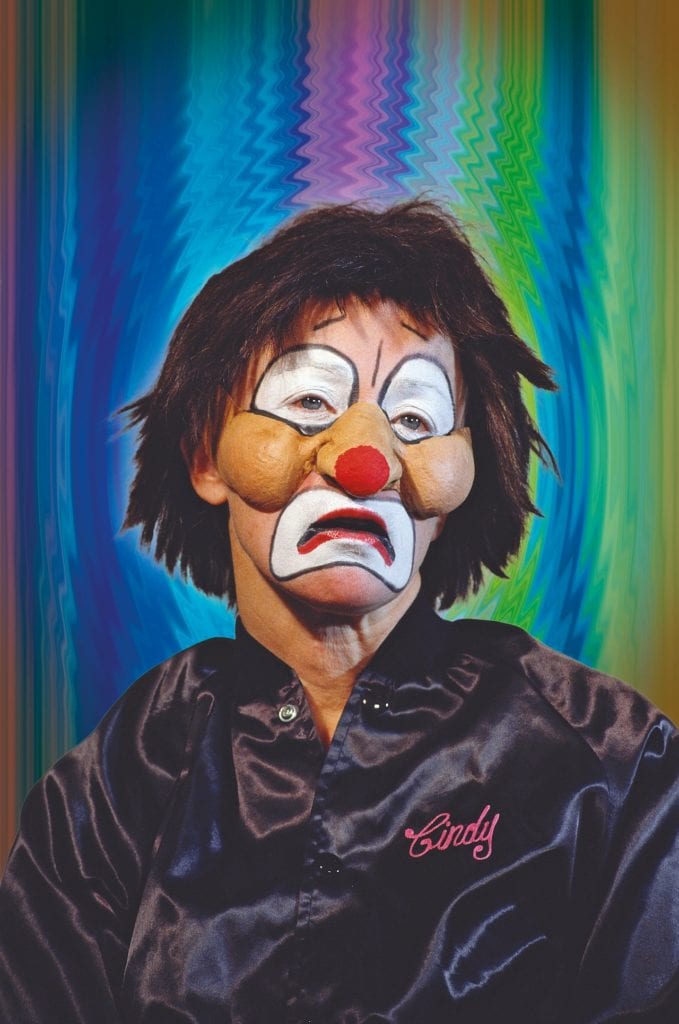

Elsewhere, expect to follow an arc of the artist’s trajectory across her most important but emphatically untitled series, with attention given to most recent bodies of work in colour, informally referred to as rear screen projections, centrefolds, fairy tales, sex pictures, masks, headshots, clowns and society portraits – all linked, fluid and utterly subversive. Sherman famously works alone on the actual shoot but with the impression that somebody is there beyond the frame (or mirror), taking full control of her use of wigs, make-up, costumes, props and even prosthetics.

The moment of its articulation consists in the palimpsest of layers of referentiality and self-conscious interpretations of style, gestures and tropes of womanhood. Sherman’s work plays particularly with imitation, parody and mimicry – but crucially they are still recognisable as ‘fakes’ by virtue of the artificiality of the settings, materials and lighting. Her whole critical, conceptual project is present in every photograph.

After all, Sherman is a consummate postmodernist: notions of pure truth as illusion, revealing a profound and sophisticated questioning of the very fundamentals of social structure and its institutions – as well as the aesthetics and seduction of cinema, television, advertising and fashion – all come to bear in her imaginary portraits. It is as if they spring from the fault-lines between façade and identity, with sharp observation to expose its deceptions, namely the manner in which the latter is manufactured and projected; the way identity speaks and vibrates through it own theatricality.

However, despite a life of manipulating her own appearance for the camera, there is a tacit understanding that Sherman’s photographs are not self-portraits. Curator Eva Respini, who authored an influential essay titled, Will the Real Cindy Sherman Please Stand Up? in the accompanying catalogue to the 2012 MoMA New York exhibition, observes: “The fact that Sherman is in her photographs is immaterial, but the ongoing speculation about her identity gets to the very heart of her work and its resonance. The connotation of actor, artist and subject, and Sherman’s simultaneous presence in and absence from her pictures has driven much of the literature on her, especially in relation to debates about authorship in postmodern art.”

Comprehensive survey exhibitions of Sherman’s work like this inevitably reflect the changes and passing of time of the artist’s own body, transcending initial critiques of stereotypical mass media representation to considering the body and sense of self as a relational construct. Sherman also questions the veracity of the photographic image and the nature of reality in itself; imitations of both life, art, and, by natural extension, art history. That Sherman can also present herself at the level of the Instagram selfie (her account has 251k followers) is an intriguing development, and points to an artist never resting on her laurels, continually taking risks. Nicholas Cullinan, director at the National Portrait Gallery, has commented that Sherman’s works now “appear more relevant and prescient than ever in an era of social media and selfies”.

Hopefully the museum will resist any temptations to pair Sherman’s photographs against paintings and limit this to the stated juxtaposition of Ingres’ 1856 portrait of Madame Moitessier with Sherman’s version of the famous history painting. Despite attempts to locate the work in the context and history of portraiture, this strategy often only reduces complexities and merely works to seek out visual echoes and compositional kinship between works across genres, geographies and time. It usually results in nothing more than studies in how much a work closely resembles its source, and largely serves to reinforce photography’s own long-standing status anxiety.

For all her critical acclaim, Sherman has been highly collected and thus enjoyed tremendous market success, with her work among the top five photographic artists by sales value in 2018, according to ArtTactic, sitting alongside Richard Prince, Wolfgang Tillmans, Andreas Gursky and Irving Penn.

Sherman is clearly one of the most important artists of the 20th and 21st centuries and this historic exhibition charting her career to date should be a must-see. Whether it can truly do justice to the sheer range, innovation and influence of her prolific output, while imparting new scholarship on her working processes, will be the making of the exhibition.

This article was originally published in the issue #7885 of British Journal of Photography magazine. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.