Born and raised in Basildon in Essex, CJ Clarke grew up assuming he’d leave. “Just to stand on any street on a warm summer afternoon is to become engulfed by a silence – a silence so vast that time seems to have disappeared,” he explains in the afterword to his book, Magic Party Place. “On such days, it really does appear like nothing has ever happened or will ever happen in the town.”

His escape route was image-making, and he moved to London years ago to study documentary photography at the London College of Communication. Like many, he had been politicised by Britain’s involvement in the Iraq war, and his first thought was to pursue photojournalism in the Middle East, in an attempt to understand Britain’s ignoble part in its history. But after travelling to Lebanon in 2005 to cover the elections, he met Judah Passow, a photojournalist born in Israel, who encouraged him to think again – and in particular to believe “that there was something worth exploring at the heart of my unremarkable hometown”.

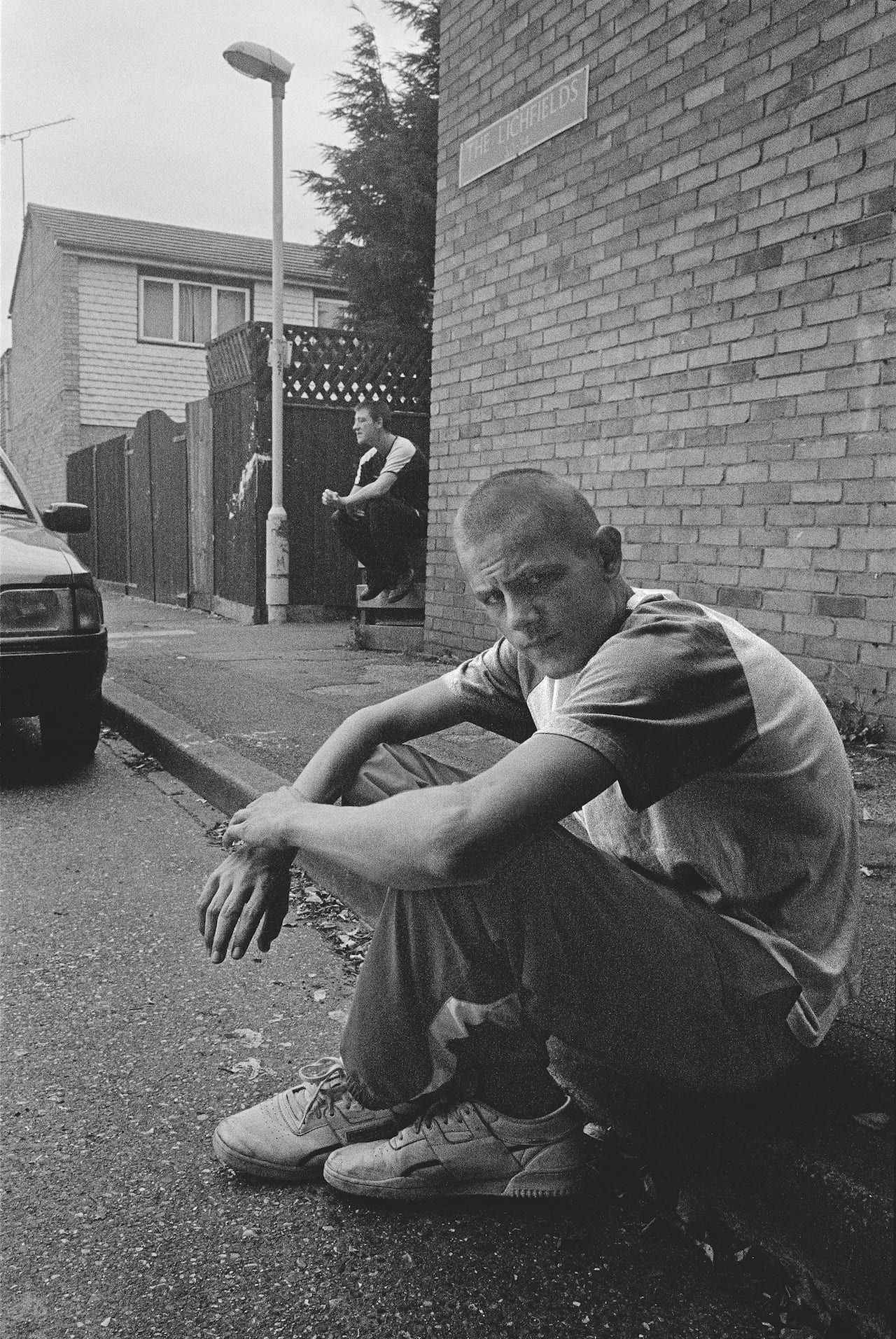

Clarke ended up moving back to Basildon and photographing it for a decade, a lengthy commitment which, combined with his insider knowledge, means his book has a noticeable subtlety and depth. A new town largely built in the 1960s, Basildon was once a symbol of the aspirational white working class who had left London to start anew, the phrase ‘Basildon Man’ shorthand for its ruggedly independent mindset. But more recently, attitudes towards the working class have hardened in the UK, and people from Basildon are now more likely to be snobbishly dismissed as tacky ‘Essex Girls’ or oafish ‘White Van Men’ – or, worse, feral youths alienated from society and intent on destroying it.

Clarke’s book engages with the propaganda but also attempts to complicate it; he shows a group of lads on a fading 1970s housing estate, for example, but his image has a sense of dignity and warmth. “The young guys on the estate understood the problems of representation and what I was trying to do more than anyone else,” he says. “The people getting a rough ride for antisocial behaviour and dropping out of school were some of the sharpest I’d met.”

Clarke photographed friends, family, and people he got to know along the way. There are portraits of individuals, taken as they light up a cigarette or hang out at home, and there are shots of raucous nights out, taken on a disposable camera to help him blend in. There’s a beautiful picture of four elderly women in a restaurant, looking rapt at a podgy young toddler; there are aerial images showing the rigid structure underpinning a town raised from next to nothing. Another image shows three neon words shining out of the black of night, ‘Magic Party Place’, providing Clarke with the title of his work.

As a result, the book shows much more than the media stereotypes, and Clarke sometimes makes this point quite literally by including newspaper headlines (all but one from The Daily Mail) alongside his more nuanced shots. “Road rage driver jailed for 25 years after spraying acid in the face of an innocent motorist” reads one, opposite a photograph of an older man taking a proffered ice-cream. “Police officer injured after sofa thrown from van which then crashes: two arrested on suspicion of attempted murder” reads another, opposite a shot of a handmade poster about a missing dog.

Clarke finds the headlines “bizarre”, and points out that Basildon is actually statistically completely average, “a kind of ‘everyplace’ that says something about contemporary England”. The stats listed in the book back him up: Basildon may be slightly whiter and less diverse than the average, but it is otherwise in line with contemporary English norms of education, employment, housing, crime, health, and relationship status. The mismatch between the reality and the perception makes him question “our conception of what is normal or average”, he says, and many readers will feel the same.

“These places are normal and average because most people live in communities that are similar to this,” he says. “They’re not unusual in that sense. The majority of people who would describe themselves as working class, or live in such places, live in average England, but when I started it I felt the working class was only interesting [to the media] if they were doing something extreme – if they were criminals or drug addicts or, I don’t know, beating grannies up on the street. That’s the only time The Daily Mail was interested. Within photojournalism there seemed to be this interest in the extreme, but the extreme doesn’t represent the majority.”

He believes the people of Basildon and Essex are misrepresented by these depictions and, more than that, actively disempowered by them. “Essex Girl or Basildon Man, or whatever – they pigeonhole and denigrate the working class, just stereotyping them and either not listening to their voice or shutting down their aspirations,” he says. “Because, what’s frightening for the political class or the media class or whatever is that this whole bunch of people are saying, ‘We don’t need you, you don’t represent us’. So instead of dealing with that, they squash them down.”

It’s appropriate, then, that Clarke didn’t publish images from the project before turning it into a book – knowing it wouldn’t edit well into a 12-picture story and wouldn’t fit into any competition framework. He had always conceived of it as a book and, attending the Chobi Mela festival in Dhaka, he met the renowned Dutch designer Teun van der Heijden, who said he’d like to take on the design, suggesting different papers to break up the narrative. “I was quite happy to hand the picture edit over to him; you need that when you’ve been working on something for 10 years,” says Clarke. “You can easily get stuck into your ways of seeing and your ways of sequencing.”

The book also includes quotes from people who live in Basildon, many of them from the older generation that first moved there and helped create the community. At the back of the book is a hefty 20-page section including seven pages of statistics on the town, texts by academics on its history, and a personal insight into the project from Clarke. Including this section was crucial to him, he says – his day job is as a video director and producer, where he’s used to “looking for good stories and representing people with dignity” but also “producing work that’s underpinned by statistics”.

“One of the reasons I continued so long is that I always had a clear conception of what I was trying to do and say, and it was always underpinned by facts, giving the work journalistic integrity,” he explains. “It’s underpinned by research, so it’s not just an opinion, it’s an informed opinion.”

cjclarke.com Magic Party Place is published by Kehrer Verlag, priced €45, available at artbooksheidelberg.de Magic Party Place = New Town Utopia, an installation featuring work by CJ Clarke and Christopher Ian Smith, is on show until 27 April at Rich Mix, 35-47 Bethnal Green Road, London E1 6LA. Entry is free https://richmix.org.uk/events/magic-party-place-new-town-utopia/