In 1919, a year after the end of World War One and the start of the Weimar Republic in Germany, $1 was worth 48 Marks. By early 1922, $1 bought 320 Marks; by late 1922, $1 bought 7,400 Marks. By 1923, $1 bought 4,210,500,000,000 Marks. “Lingering at shop windows was a luxury because shopping had to be done immediately,” said the artist George Grosz at the height of this hyperinflation.

“Even an additional minute could mean an increase in price. One had to buy quickly. A rabbit, for example, might cost two million marks more by the time it took you to walk into the store. The packages of money needed to buy the smallest item had long since become too heavy for trouser pockets. I used a knapsack.”

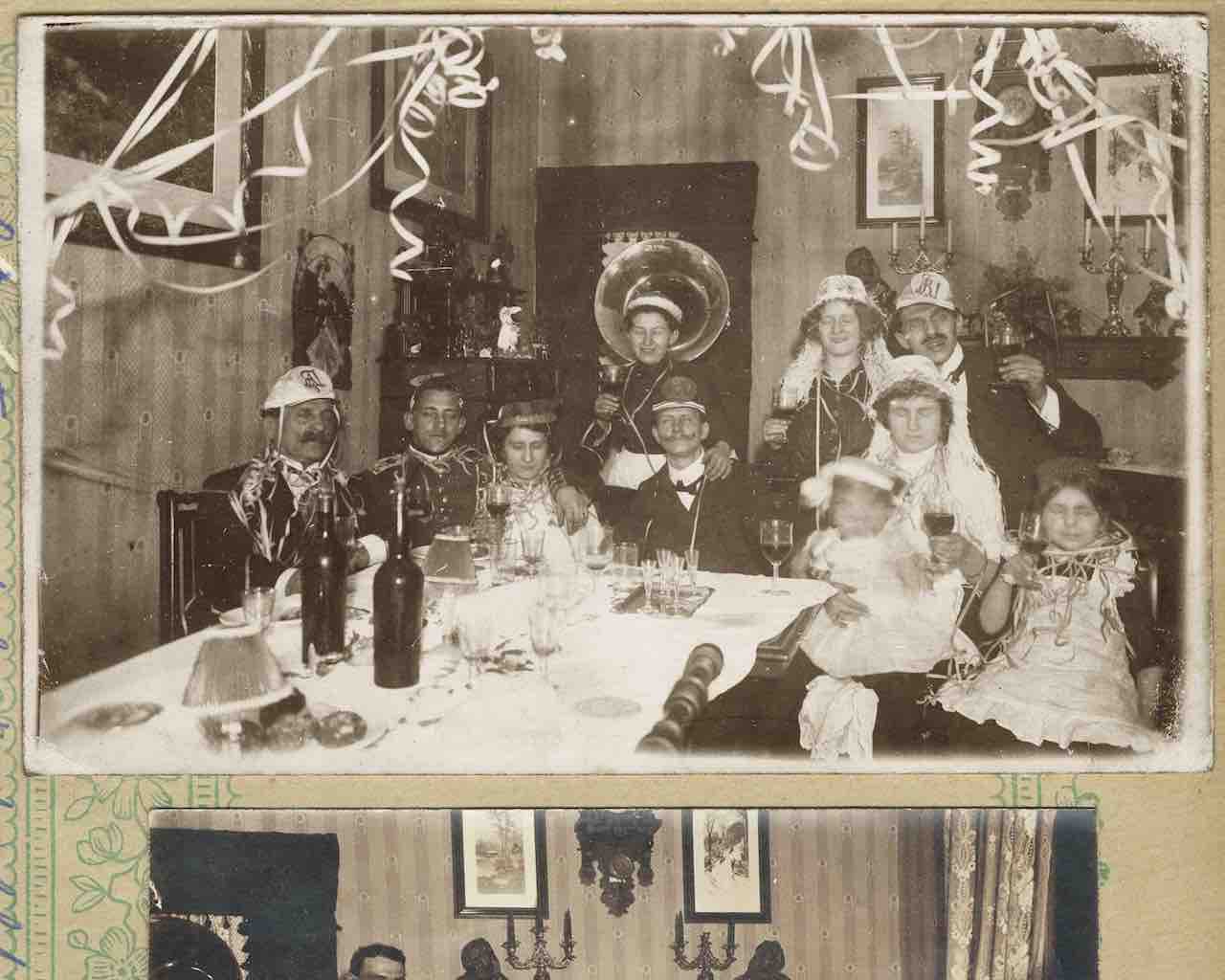

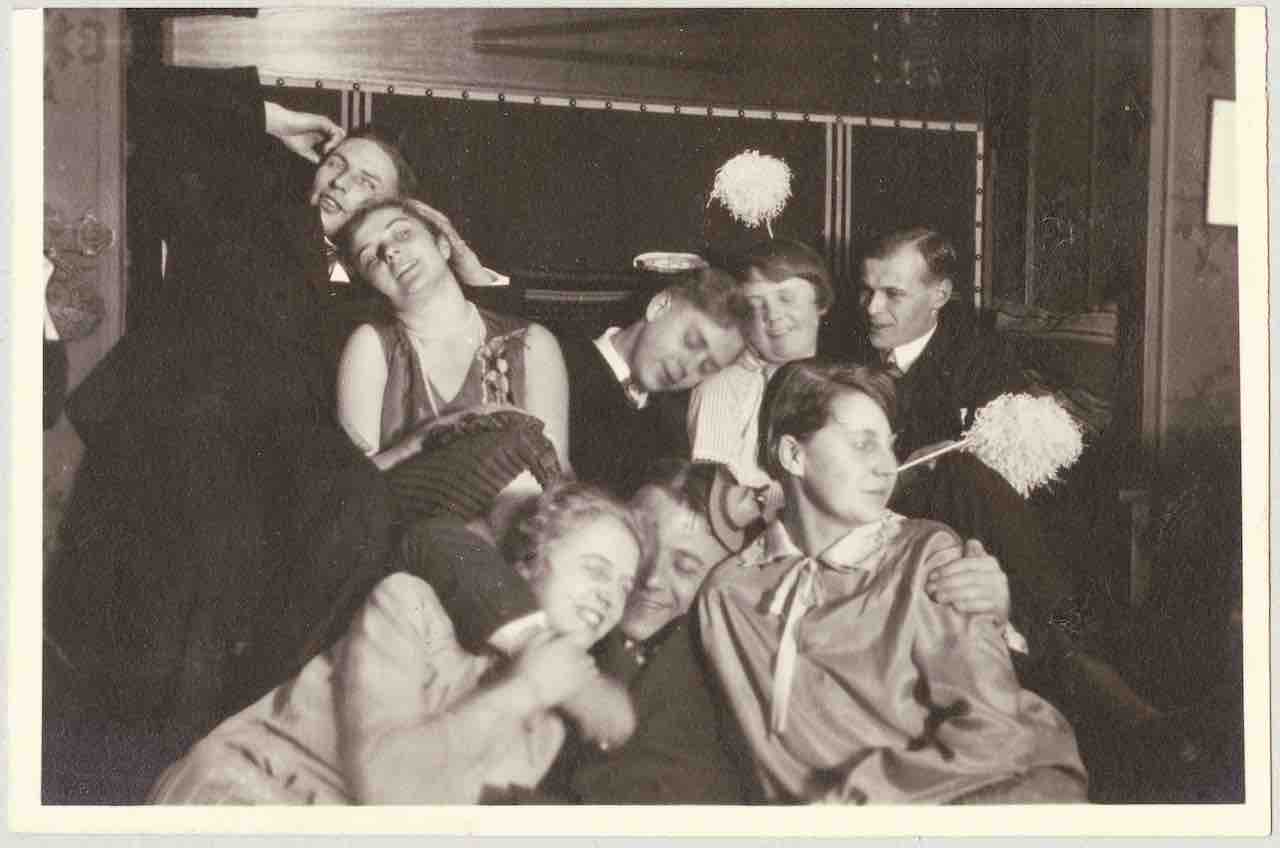

Ravaged by the experience of war, Germans threw themselves into partying in the 1920s. In this they were not alone – the 1920s, after all, were the time of the Jazz Age in America, and the Bright Young Things in Britain. But the experience of defeat, and the parlous state of the German economy, made the partying of the Weimar Republic particularly intense. “In Paris, if you can’t make your living through dancing, there will be some sympathetic Marquis or American, but in Berlin even God ignores you!” said Dey, an American Creole dancer celebrated for combining belly dance with the Charleston.

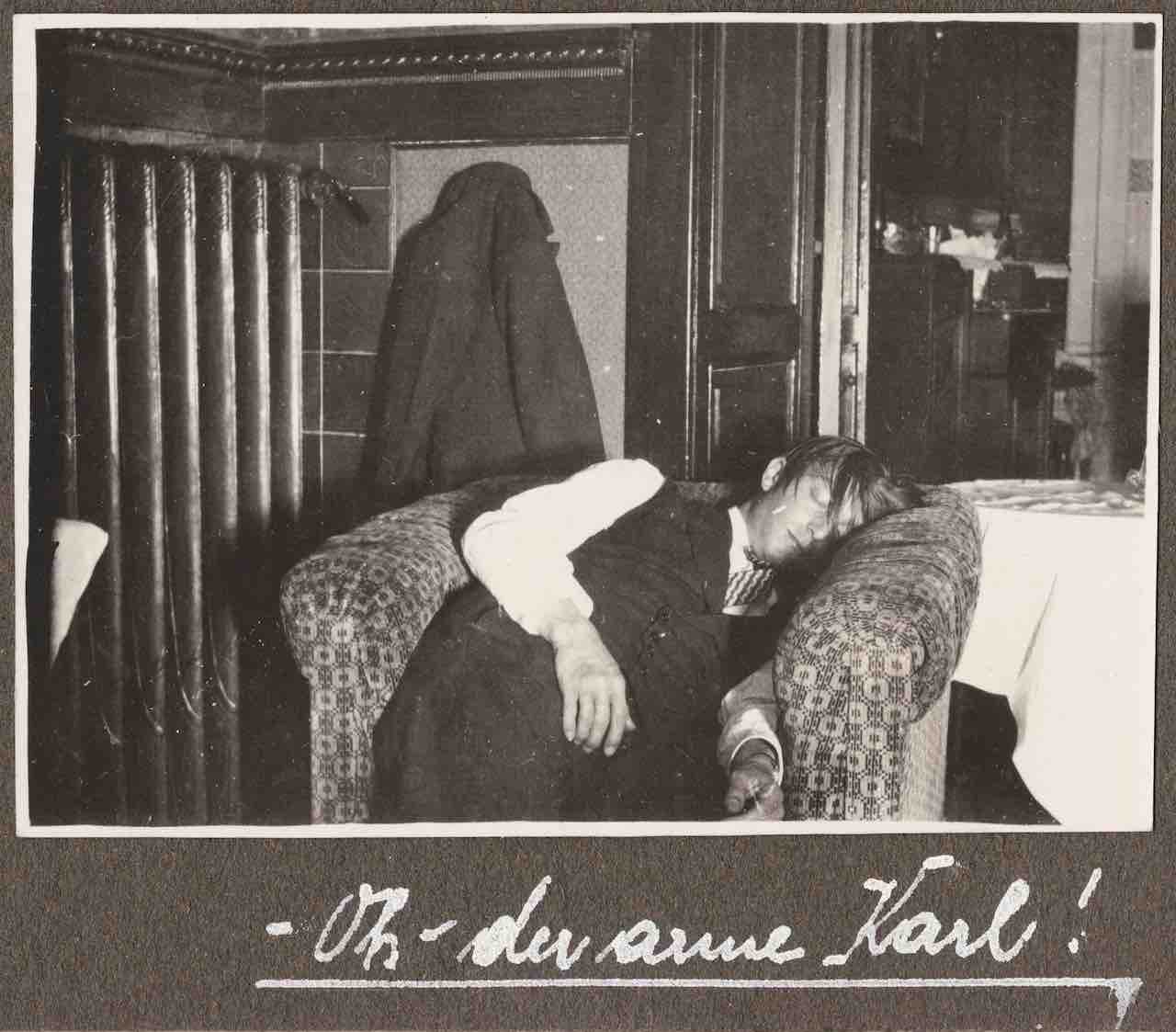

Dey and Grosz are quoted in the Archive of Modern Conflict’s new book, Party! Party!! Party!!! a compilation of previously unpublished images of German parties and clubs from 1919 to 1934. Presented chronologically, with text explaining some of the context of the time, or the origin of the images, or contemporary recipes for Heißer Punsch (includes one bottle of rum and serves two), the images present an image of a fun-loving whirl that we inevitably now read through what followed.

There are hints of darkness to be found. There’s the Kirchner family album, for example, whose images of parties and picnics abruptly end in 1929, the year of the Wall Street Crash. The Nazis had been about since 1920 but it was only in 1930, as the Great Depression spread, that Hitler’s party became a political force. By 1932, Swastikas and portraits of Hitler have started to appear in the photographs. By 1934, the year of The Night of the Long Knives, it’s all over.

Based in London’s Holland Park, the Archive of Modern Conflict is a weird and wonderful cornucopia, which specialises in collecting vernacular photography, objects, artefacts and ephemera. It’s backed many books and projects over the years, from Stephen Gill’s original photobooks to Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin’s Holy Bible, a mashup of the celebrated translation and images of conflict.

In 2007 it published Nein, Onkel, a disturbing vision of Nazis at play that dared to suggest that, far from the pantomime baddies familiar from fiction, the Nazis could look – maybe they could even have been – people, not so dissimilar to you or me. In Party! Party!! Party!!! editors Ed Jones and Christopher Nesbit have recaptured something of that chill factor, with images that suggest how thoughtlessly, even how deliberately, the fun can go on while fascism blossoms. The question, it seems in the end, isn’t what you did in the war, but what you did to prevent it starting.

Party! Party!! Party!!! edited by Ed Jones and Christopher Nesbit is published by the Archive of Modern Conflict https://archiveofmodernconflict.com