Born in Barcelona in 1971, Txema Salvans is still based in the Catalan capital, and specialises in making documentary work about Spain and the Spanish people. He is best known for his book The Waiting Game [2013], which showed lone women, presumably prostitutes, waiting by the sides of roads along the Mediterranean coast. Salvans spent six years shooting this project, and recently published The Waiting Game II [2018], a series showing fisherman on the Mediterranean coast, waiting for the fish to bite. In 2010 he published Nice to Meet You, also shot along the Mediterranean, a book of ‘family photos’ in which some of those shown weren’t family.

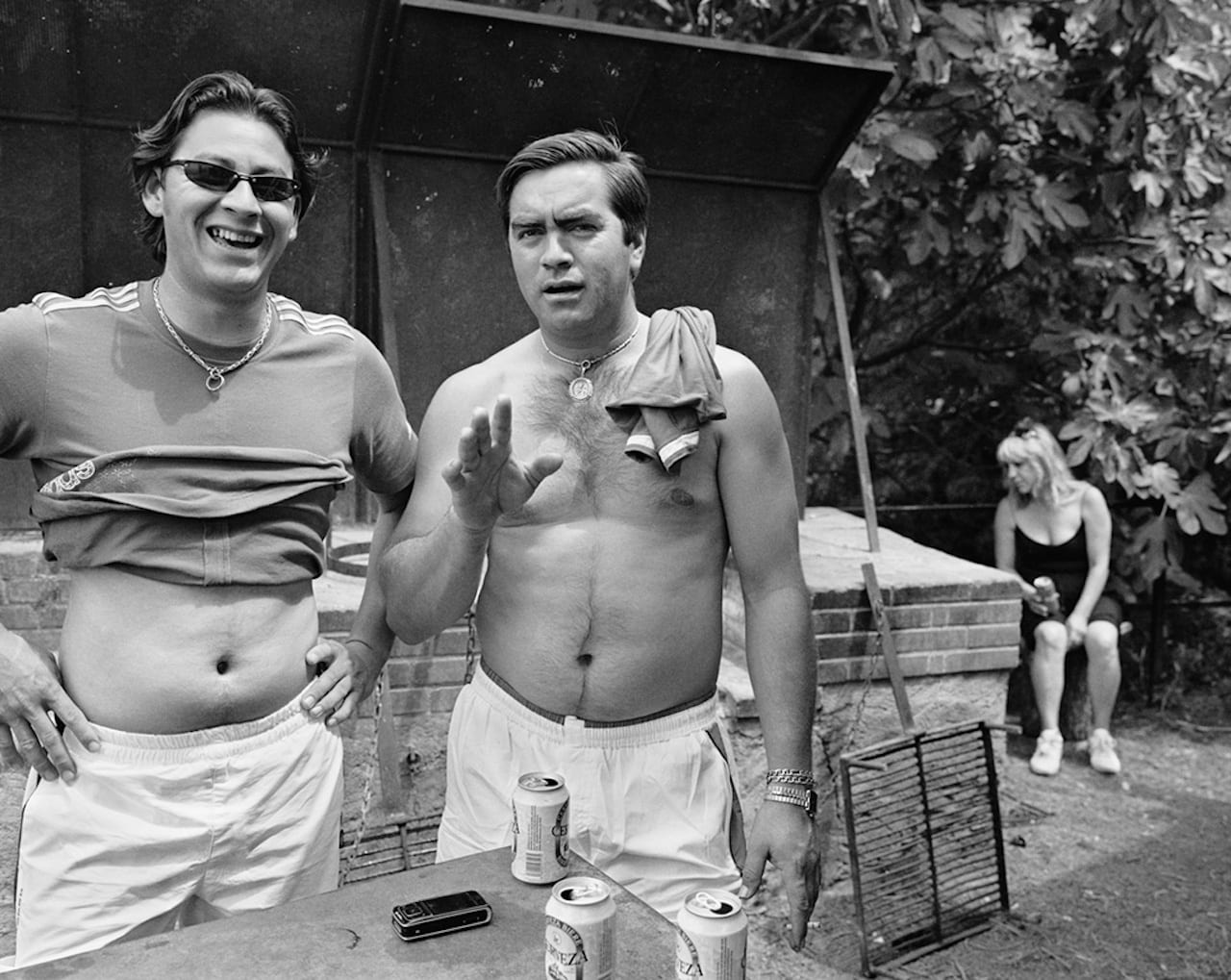

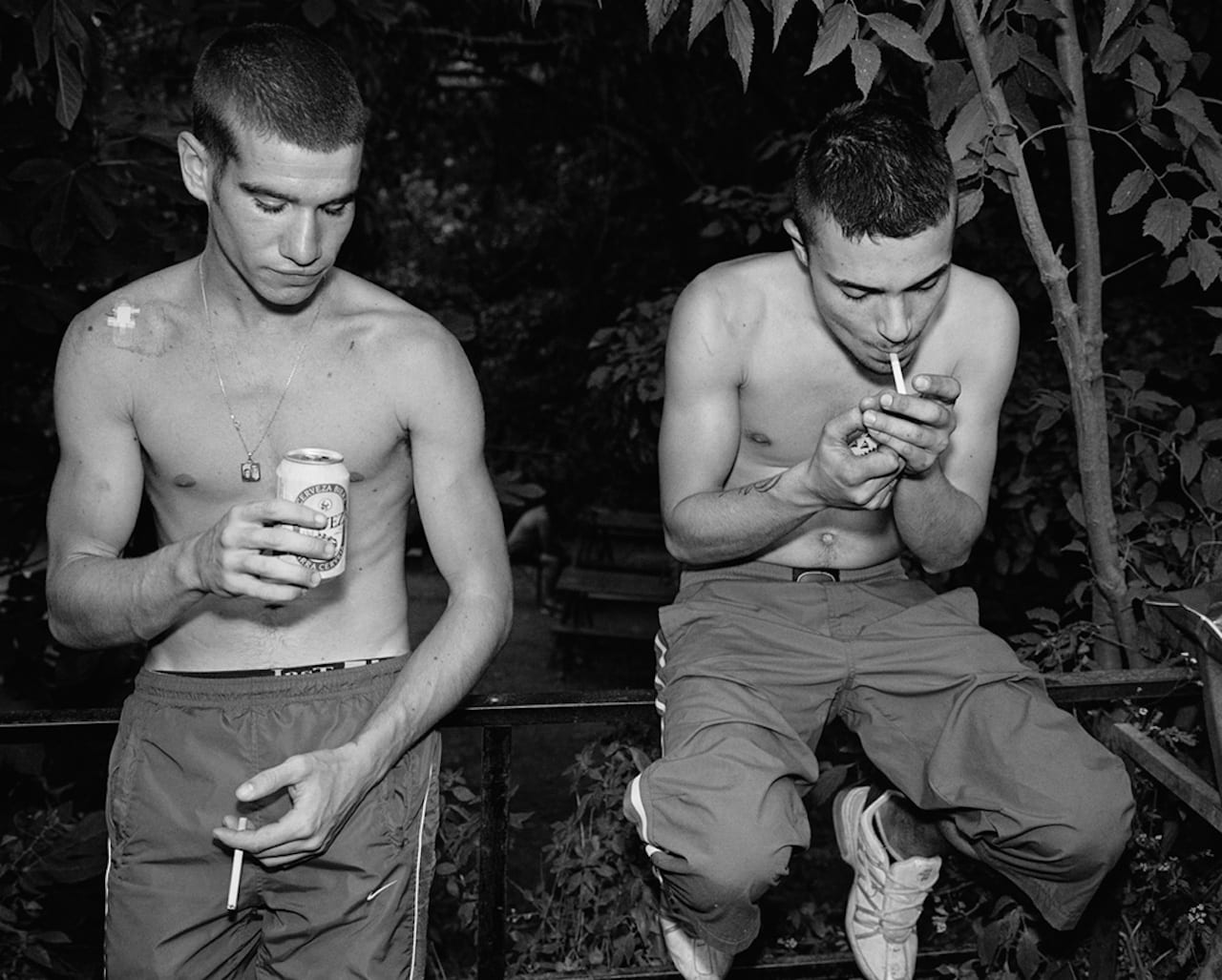

His new book, My Kingdom, recently published by MACK, originally grew out of Nice to Meet You, and shows Spanish people and families relaxing on the Mediterranean coast. Its title is taken from a speech by King Juan Carlos I, however, who ruled Spain from 22 November 1975 – 19 June 2014, and extracts from his speeches run throughout the book. It is, says Salvans, a book about power rather than about Spain, the Spanish, or King Juan Carlos I. BJP caught up with him to find out more.

BJP: My Kingdom is framed by speeches by King Juan Carlos I. Why did you decide to use his words?

Txema Salvans: I am always working on different series, some I have a very clear idea about, others are purely intuitive and only little by little become more defined. This is what happened with My Kingdom – as time passed and the project grew, I realised that these photographs could illustrate more than the simple idea of Spaniards on vacation. I could add complexity to explain more, though always with good photos. Over the last few years, Spain has lead Europe in terms of crises and bad politicians. I decided to politicise the series, to make a work that talks about power.

BJP: What does Juan Carlos represent in the book? The first quote you have used by him seems deeply ironic – he references becoming King owing to historical tradition, when in fact he was put in power by Franco. On the other hand, he dismantled Franco’s regime and paved the way for the return of democracy.

TS: King Juan Carlos grew up under the tutelage of Franco, and it was the Franco regime that decided that, on the death of the caudillo [‘leader’, but also ‘military dictator’] the monarchy would be restored. It seemed very revealing to me that in the investiture speech the figure of the King was justified in this way, ‘As King of Spain, title vested in me by historical tradition’, not a democratic act. In the same way, all the coins [pesetas] which featured Franco’s face featured this text – ‘Caudillo de españa por la gracia de dios’ [‘Caudillo de españa by the grace of God’]. It seemed very significant to justify these infinitely subjective decisions by historical tradition or by a divine act.

I was born in 1971; Franco died in 1975, the same year that Juan Carlos became King of Spain. Juan Carlos then accompanied us throughout the transition [from Franco’s regime to democracy] until his abdication in 2014. The texts throughout My Kingdom are taken from the Christmas speeches he made throughout his reign. These speeches always had a large audience, because the king represented modernity and a new era. But they were always paternalistic, seemingly aimed at an audience that took his destiny, his position in the world, as a given.

I have printed these texts using same typography used by teleprompters, that invention that allows you to read a text that you have not written, and which you do not need to believe, looking directly into the viewers’ eyes. All that is needed is a reader who seems honest.

BJP: Who are the people you have photographed?

TS: I wanted to focus on Spanish families on vacation, enjoying the Spanish Mediterranean. The book begins with a picture of my own family, Laura, Jan and Bruna, having a picnic in a service area of the Mediterranean highway. For me it was important to show that this work was done from within, that it is not an aesthetic look in from the outside. The people I photographed are those who listened to the King’s speeches, they are ‘the kingdom’ of the King – people who grew up with him, and who each formulated an idea about him.

Every summer, the King was photographed with the whole Royal Family on his yacht (a gift from Spanish businessmen), or his palace in Mallorca – in contrast to the more modest beaches and apartments that Spanish people typically go to. But here is the strange thing, ‘My Kingdom’ not only refers to the territory over which a King reigns, but also the things we all fight for – our car, our friends, our holiday apartment, our piece of beach, our son, our credit card, our body…This book is not a criticism of a specific character, but an analysis of a system, or even of a human trait.

BJP: The people are photographed sympathetically, and in soft black-and-white (compared to, say, the strong colours of your earlier project Welcome Aboard). Why did you choose to show them like that?

TS: When I finished my first book, Nice to Meet You [published in 2010], I decided to keep working with the same territory and subject – how people manage their free time. But I decided to change my point of view, so I changed my camera from a 35mm to a Hasselblad 6×6 and Mamiya 6×7. Each camera has its own peculiarities, so I had to learn how to dance again. I spent seven years working on the images in My Kingdom.

I think one of my greatest achievements is that I can photograph people without making them look ridiculous, although there is a lot of irony in my work. It’s something I do naturally, I have that intuition, but the most important thing is the edit, in which you can decide to reinforce certain aspects. Never be afraid to edit out a good photo if it doesn’t contribute the overall project.

My photography requires a lot of discipline. Because I shoot at home in Spain, there is nothing new for me – nothing aesthetically unknown, no strange customs, as can happen when you travel to other countries. But this means there is something in my favour, that my voice has value because I know and I am part of what I have photographed. It is never an anecdote.

BJP: On your website biography you refer to photography as an intense way to look at and experience daily life – why are you interested in that? My Kingdom makes me think of Michel de Certeau’s book The Practice of Everyday Life, and the idea that people resist authority through their daily creativity and ingenuity, as opposed to submitting with some kind of mob or sheep mentality.

TS: YES! To resist! That is the word I have discovered lately. Photography came to me by chance – it wasn’t love at first sight, I wasn’t interested in technique or the darkroom. What I liked was that it allowed me to start many small adventures. I discovered something that closely matches my personality, when I started taking pictures I did it in the most beautiful and pure way you can pursue art or life – through personal joy.

BJP: Your biography also references “life-affirming” leisure, as opposed to “wage slave effort and sacrifice”. Do you think this idea also comes across in My Kingdom?

TS: I believe many conclusions can be drawn about a society from the way its population manages its free time. In Spain the leisure industry is an economic model and, like any economic model, it needs a critical mass to work. You have to educate and train the population to occupy that hotel bed, that bar chair, or that section of beach. It always surprises me when people tell me ‘We had a very good holiday, we didn’t do anything” because the goal was to do NOTHING.

BJP: Your biography also references “positive interaction” with the people you photograph, and a move away from surprise and irony in your work, towards acceptance of others. Your book Waiting Game I [which was published in 2013, and which shows women, presumably prostitutes, waiting by the side of the road] was shot without the subjects’ knowledge, something which some BJP readers criticised at the time. Do you now prefer to photograph people with their knowledge?

TS: I never ask for permission. Re The Waiting Game, when I decided to do the project on prostitution, my main objective was to put the accent on the context, because the context was the real problem. I wanted to turn a portrait project into a landscape project, showing that context, and do it in such a way that the women were not recognisable. I worked with three fundamental premises for six years.

First, the distance. I took the photograph far away from the subject, to protect the identity of the woman, and change my project from a portrait story to a landscape story.

Second, the light. Most of the images were made with the worst light you can use for a landscape image, and the combination of the distance and this light made the images mundane and desolate, removing the sexual elements from the image. Also the light meant that this activity was happening in broad daylight, in full view, with nothing hidden in the dark.

The third principle was choosing what was going to be ‘the decisive moment’. I was committed to photographing the woman and not the prostitute, so I chose the ‘waiting moment’ and eliminated the body language of the prostitute, what in biology they call ‘the display’. I eliminated all the visual elements that reinforced the sexual character of the woman.

In this project I had to reconcile two photographic concepts that I have always been uncomfortable with – first the idea that the more beautiful the image is, the more successful it becomes, even though for me, sometimes the more beautiful the image is, the more difficult it is for people to empathise with the subject of the photo. Secondly, the dominant character of the photographer, who often imposes his will over the subject being photographed. I dare to say that these two issues arise in everything from the most innocent street photography to the most exciting war photography.

The Waiting Game now has a second part or book that I have recently published, which reinforces an important concept for me – the idea that everything that can happen to a human being is happening somewhere right now, or someone is ‘waiting’ for it to happen. In this precise moment, someone is waiting to be tortured and someone is waiting for the right moment to give a first kiss. Someone is waiting to see the birth of their child, and someone is waiting to bury their child.

This ‘Waiting Game’ is universal. People, all over the world, spend their lives waiting. This is what I hope to emphasise by adding The Waiting Game II [published earlier this year], which is a series of photographs of people fishing. I’m now working on The Waiting Game III.

BJP: My Kingdom is accompanied by a booklet with extracts from speeches by figures such as Thatcher, Hitler, Mussolini, and Charlie Chaplin’s Great Dictator, declaring the power of the state over the people. Why did you include these texts?

TS: Because this book is not about Spaniards on vacation, and it’s not a book about the King, it is a book about power. I chose a selection of great speeches from history, speeches in which a speaker built the intersubjective idea of nation, and got listeners into the position where they would give their lives, and those of their children, to that idea. Closing with Chaplin’s speech is meant to be ironic.

I’m not going to take pictures from other countries, but I’m never been worried about limiting my work by doing so. I think that in talking about Spain, I can talk about global ideas – there is a universe within a drop of water as interesting as the universe itself. As a photographer I try to take good photos, whatever that means, but as an author I try to find universal concepts. I think this way of approaching projects is more interesting for my readers, and I know it is definitely more interesting for me. Finding this complexity is a challenge, and makes me grow intellectually.

BJP: Is there a political dimension to My Kingdom? It seems to have a people-first approach, do you see this as fitting in with contemporary Spanish politics?

TS: Naturally, but I have tried to be very prudent, to present documents that can work together to generate ideas. As Marx said, the accumulated knowledge of each of reader can give a different meaning to the book. This is the only way to make a book open to interpretation. The only place where I clearly position myself is in the dedication of the book [which reads, in Spanish and English: ‘Dedicated to all who live with simplicity and honesty beyond the empty words of speeches intended to imprison us; and to those who know that life is not lived behind a flag but in the fraternity of ordinary people enjoying the sunshine together on a warm day.’]

The text on the back cover is, I think, absolutely objective. I think the idea of the nation as an intersubjective idea is irrefutable, in the same way that religions or money are other intersubjective ideas.

BJP: Contemporary Spanish photography seems to be booming, how do you fit in with this scene?

TS: Fitting in with it or not doesn’t depend on me, I just keep working.

BJP: How did the book project with MACK come about? What’s it been like to work with them?

TS: I have a professional relationship with Michael [Michael Mack, founder of MACK], but when you talk with him and try to explain your ideas he is totally attentive, and immediately empathises with you. He is interested in what I do and is interested in publishing the projects that I am working on, and I am interested in working with a publisher that gives me an international platform, and that works to such an excellent standard. I hope to build a solid and lasting relationship with MACK

https://txemasalvans.com/wp2017 My Kingdom by Txema Salvans is published by MACK, priced £30 www.mackbooks.co.uk