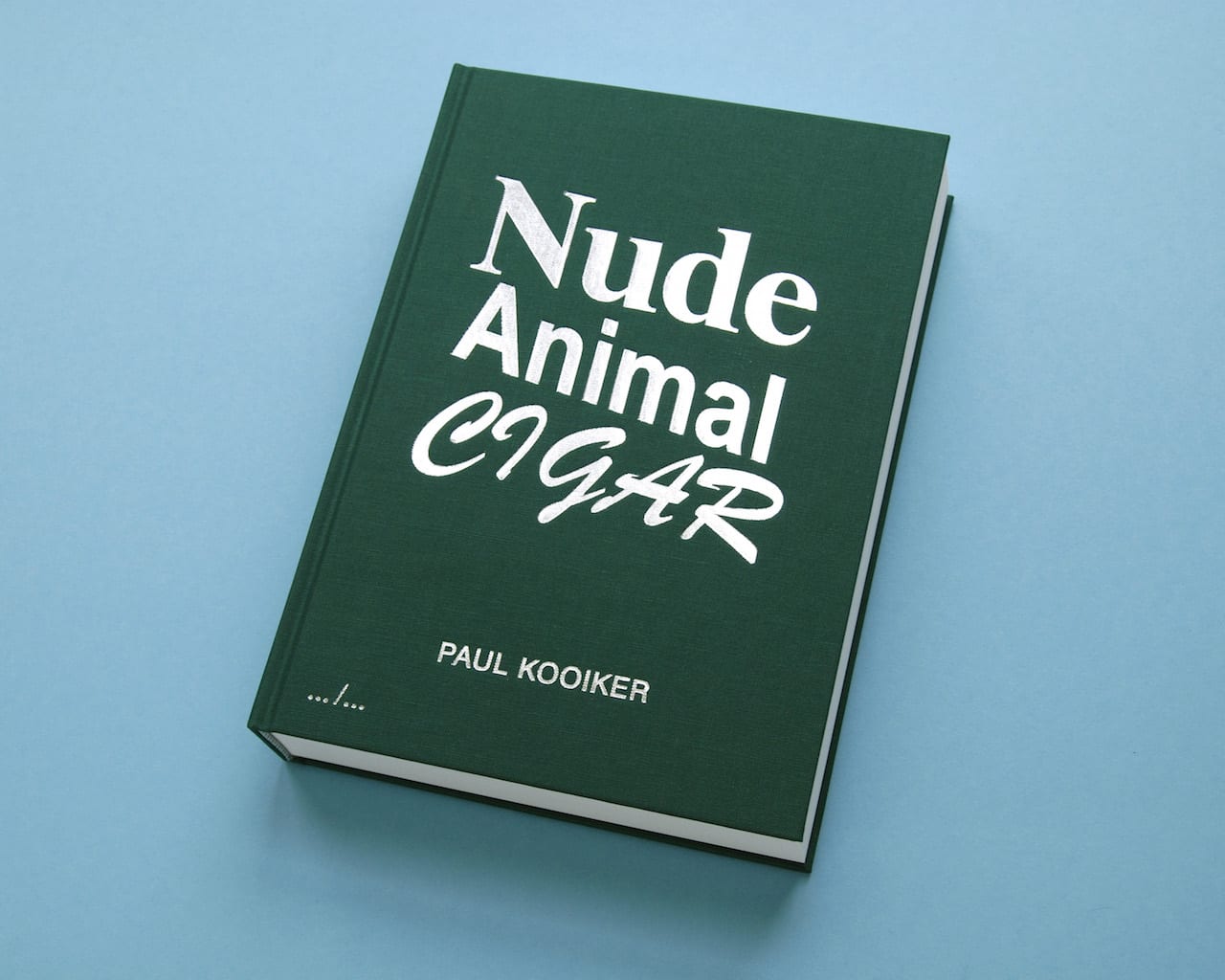

Paul Kooiker’s latest photobook, Nude Animal Cigar, is a peculiar hybrid made up of variations on the three themes revealed in the title. It’s as if the weirdest and most beautiful nudes, mournful animals and mysterious still lifes of cigar butts have been picked out from photography’s 176- year history. But although the images look old- fashioned, they have all been made within the past five years by this contemporary Dutch artist. Applying sepia filters to all the images, he lends the series a vintage and melancholy feel, and by virtue of the treatment knits this motley trio of monochrome motifs together.

“My work is successful if it is about looking, and about photography,” says Kooiker in his studio, located in a quiet street on the southern periphery of downtown Amsterdam. “Ultimately, my work is about looking, and looking is the ultimate act of voyeurism. It makes the work accessible, as everybody is able to recognise himself in this act. It also leaves the viewer confused. What I want to achieve is to make the public feel accessory to the images they witness.”

Born in 1964, Kooiker graduated from the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam in the early 1990s. In 1996 he won the Prix de Rome with a project on women weeing in the forest that set the bar for his future art; a montage of 40 colour photos, with barely discernible female nudes, out-of-focus shots, image repetition, and the implicit hint of voyeurism – a theme mentioned repeatedly by critics writing about his work. For Kooiker, photography and voyeurism are inextricably linked, and the camera is a guilty look through the keyhole, though he thinks “nothing is as terrible as erotic photography”.

Instead, he sees his work as a commentary on it. He isn’t interested in the single photograph, so his projects are always conceived as a series; in the two decades since his audacious debut, he has published book after book, bearing titles such as Hunting and Fishing, Showground, Room Service, Crush, Sunday, and Heaven. Most of them were designed and published by Willem van Zoetendaal, the Dutch gallery owner, publisher and photobook designer who retired from the gallery business last year.

Two years ago, curator Wim van Sinderen of the Fotomuseum in The Hague asked Kooiker to work towards a retrospective exhibition. However, rather than collecting a ‘best of ’, Kooiker proposed he develop a new installation, and a book in which he would predominantly show new work, or old work in a new guise. The museum agreed and Kooiker realised the project by focusing on images of nudes, animals and cigars. All three are close to Kooiker’s heart: the nudes and sometimes animal photographs had already made their way into his books, and the cigars he has photographed obsessively in recent years.

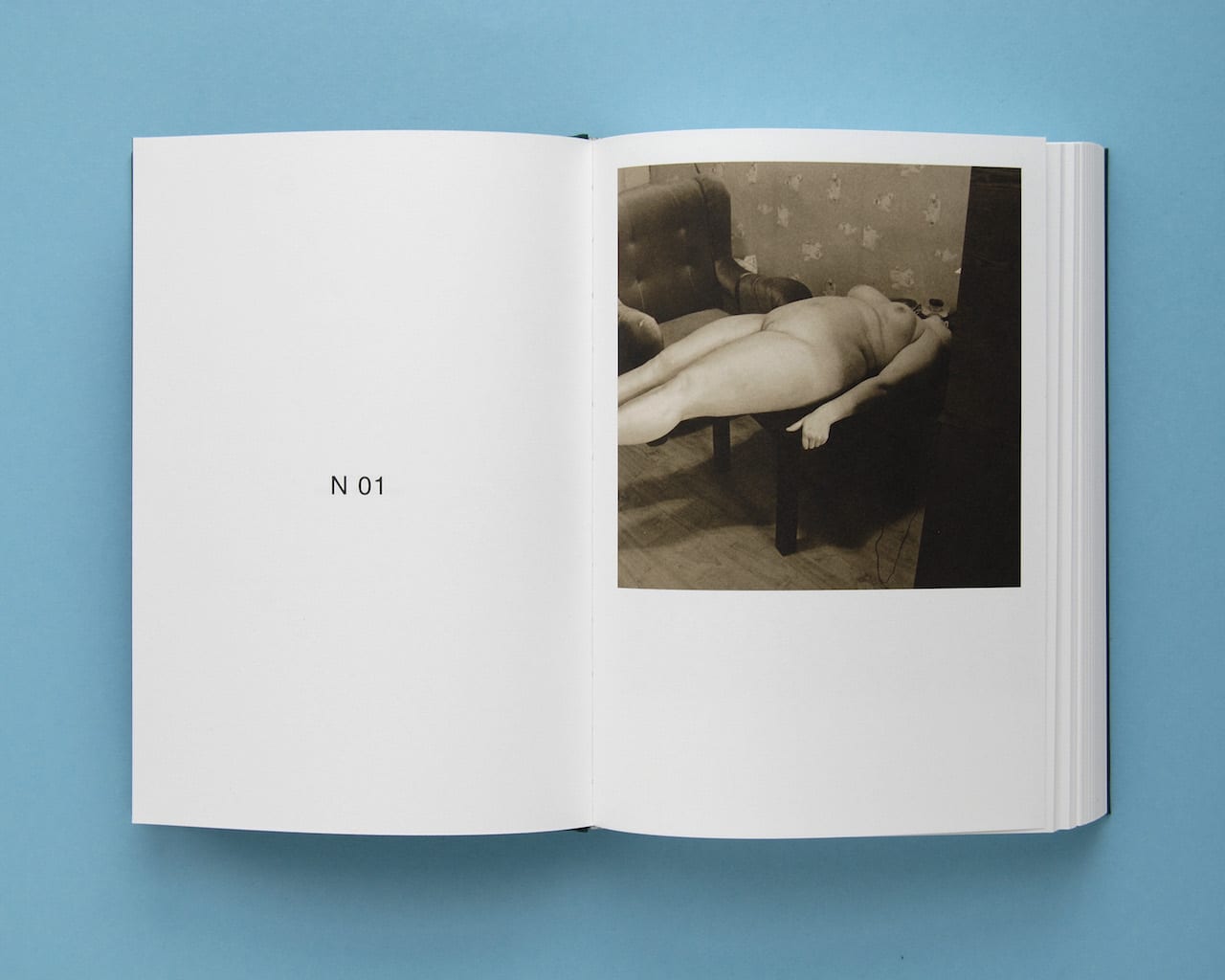

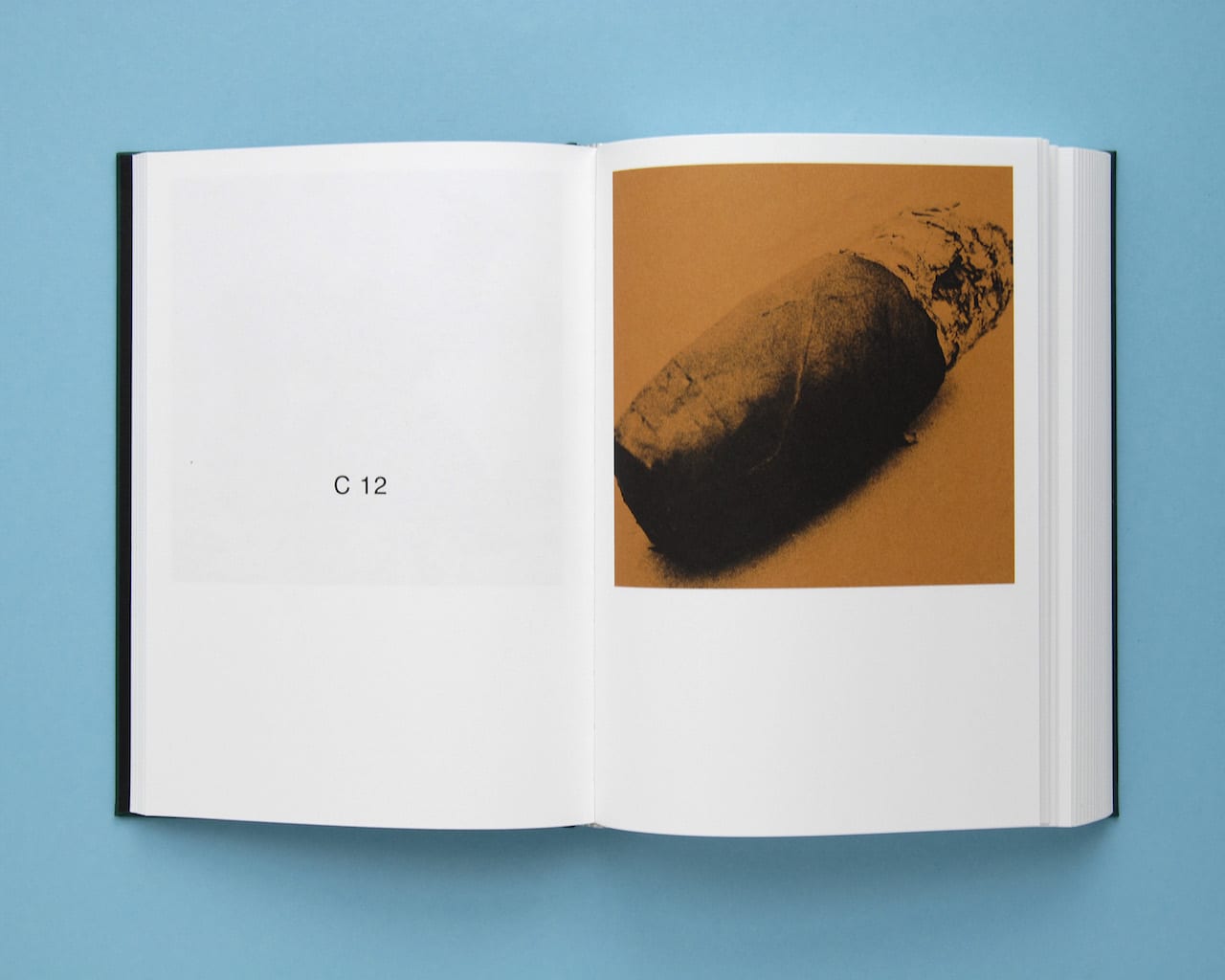

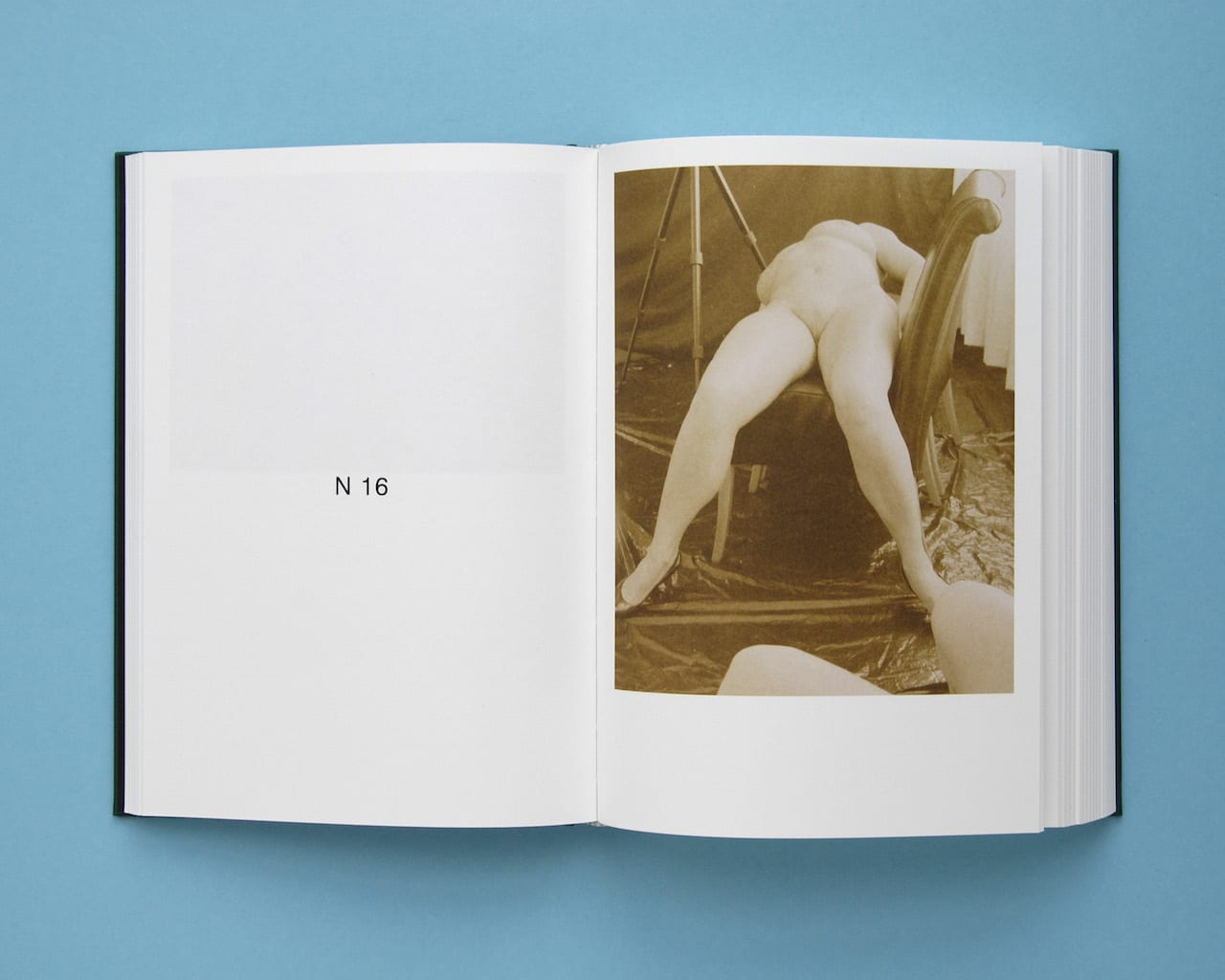

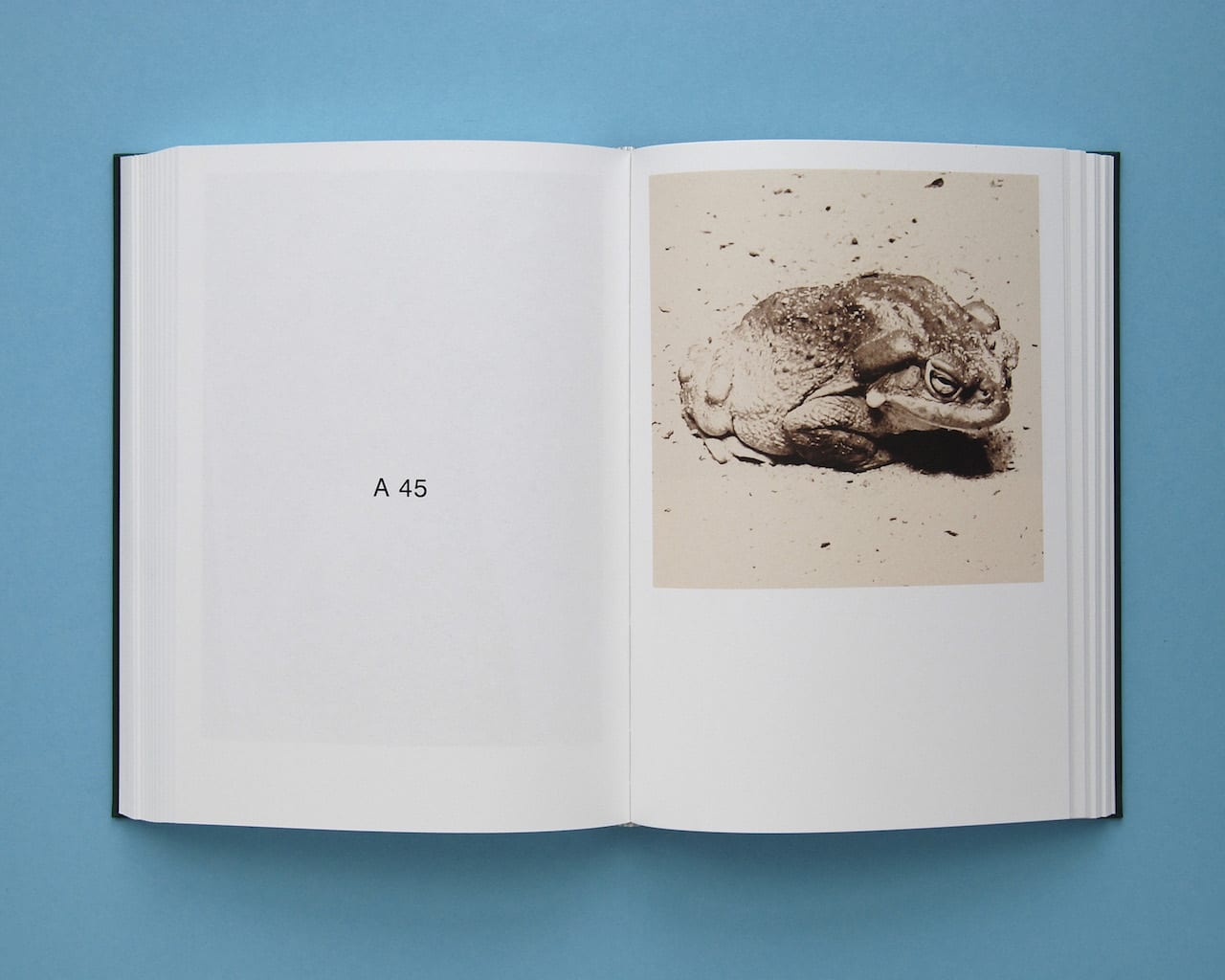

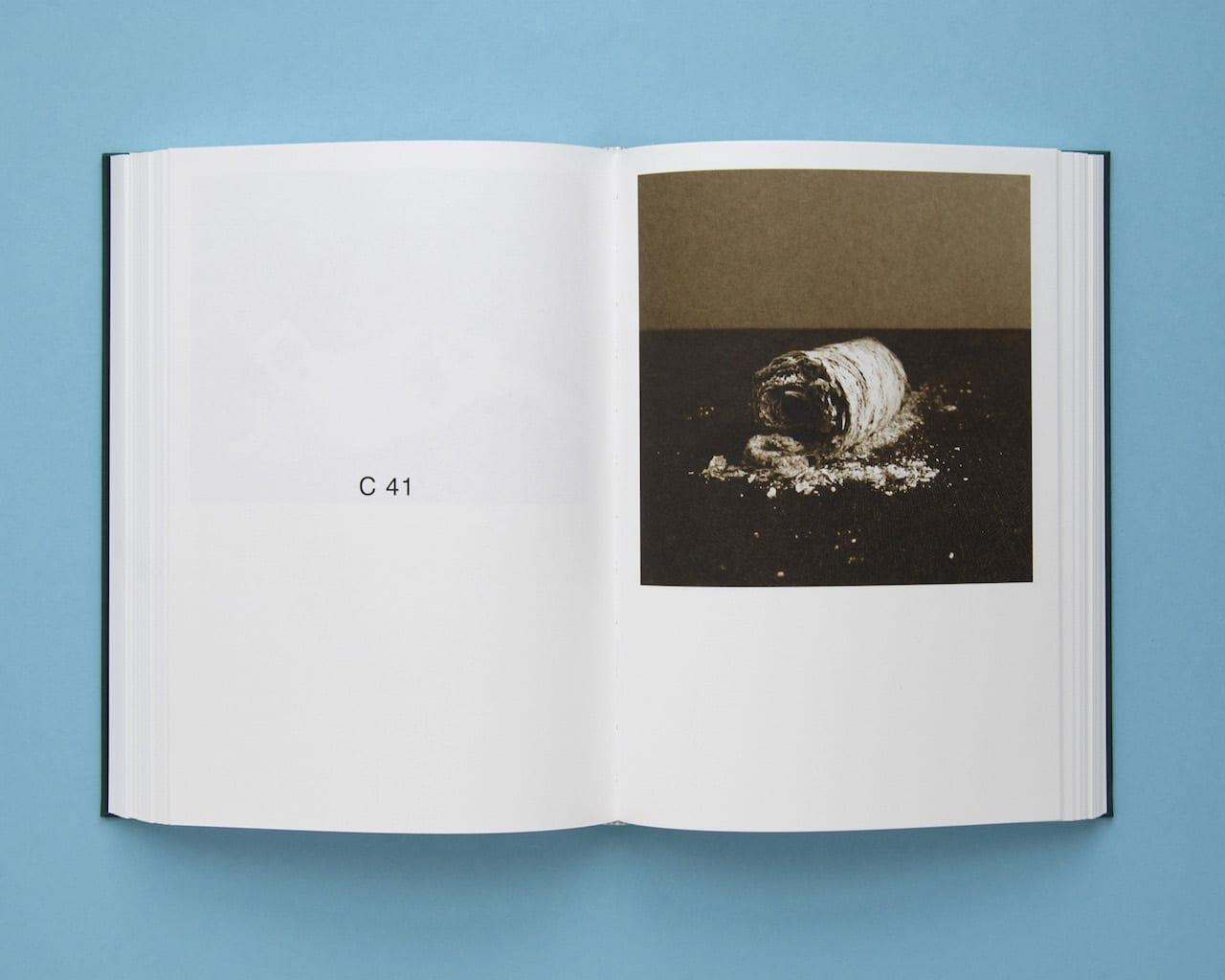

Gathering 63 photographs of each of the subjects, he made a series of large exhibition panels, loosely arranging the images into grids; the sturdy book, by contrast, follows the staccato rhythm of the title, showing 63 sets of nudes, animals and cigars in that repetitive order. The images on the right pages are systematically accompanied on the left pages with the indications N 01, A 01, C 01 and so on.

This time Kooiker decided to publish the book with up-and-coming Ghent-based publisher APE (Art Paper Editions), engaging the services of graphic designer and artist Jurgen Maelfeyt. He proved a worthy successor to Van Zoetendaal, displaying a similar feeling for how to deal with Kooiker’s work and helping create something that is neither a conventional catalogue nor a photobook. It is, says Kooiker, “a catalogue conceived of as an artist’s book”.

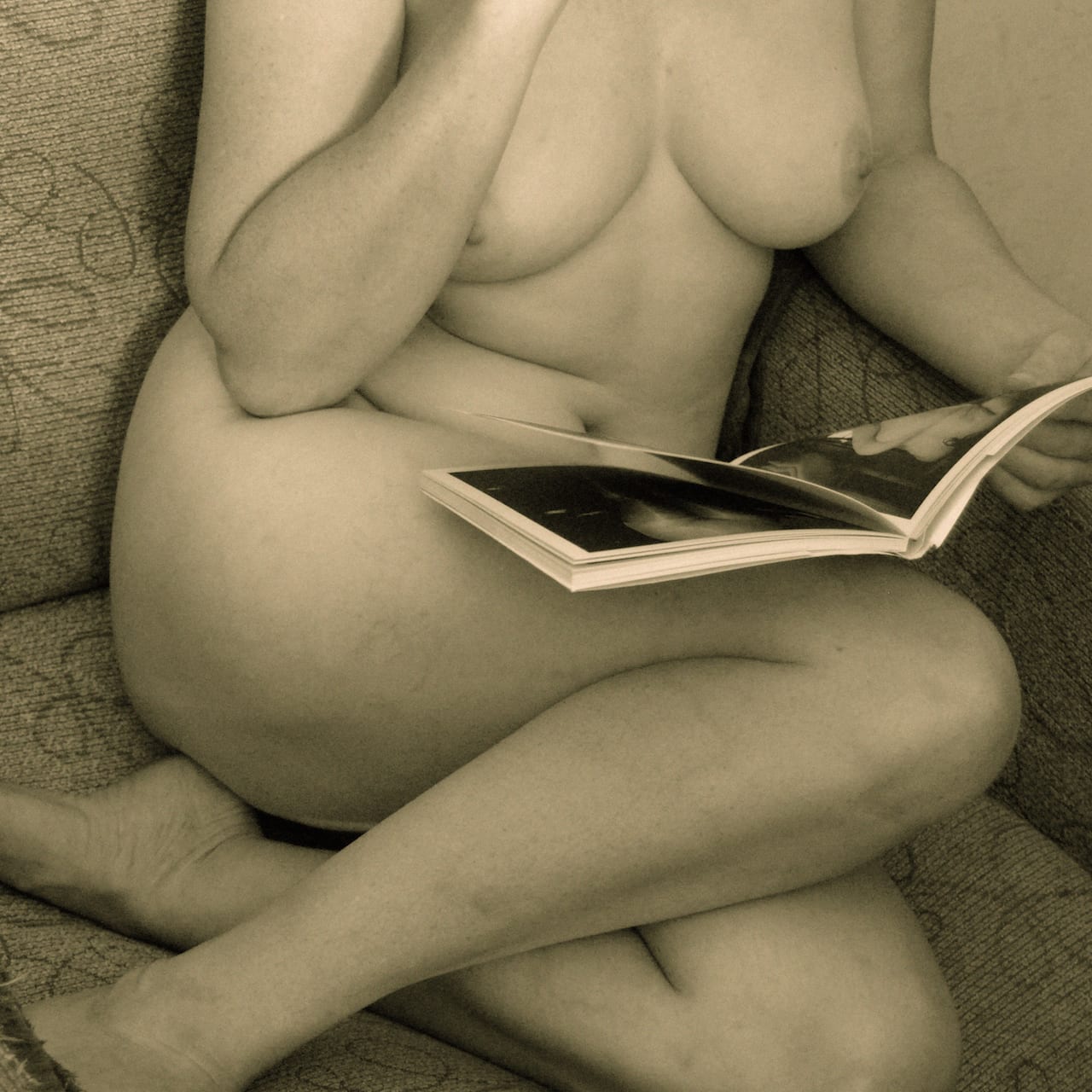

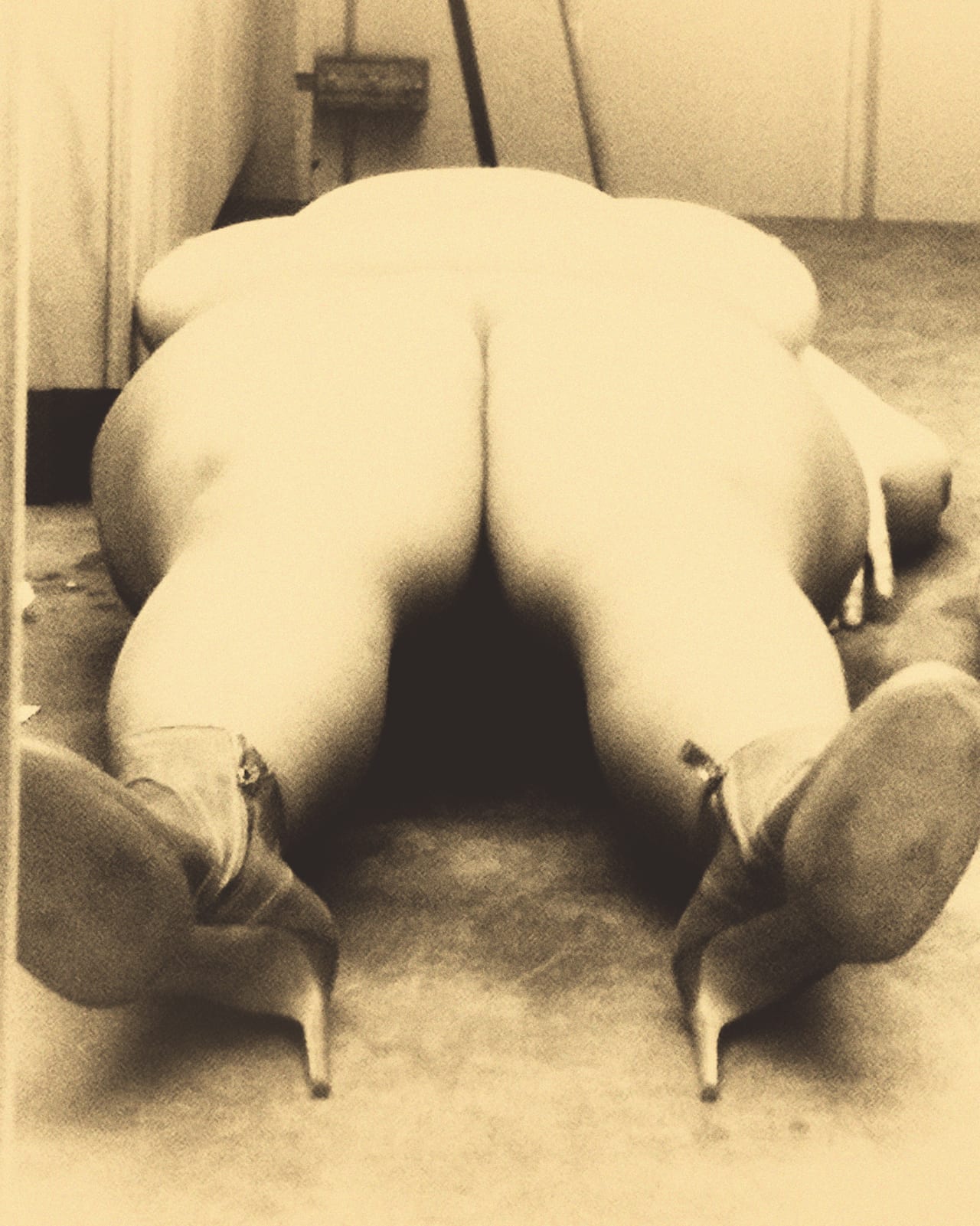

Kooiker sets a different technical challenge for each of his projects, helping unite his images through these practical parameters. In his previous book, Heaven (2012), it was the Polaroid format, which Kooiker had either used as a means of making sketches or as a basis for his processed works, mostly nudes. The series, comprising of 494 Polaroids, begins with self-portraits of Kooiker posing next to his deceased father lying in state and ends with model studies of a plump female nude, one of his recurring subjects. Surprisingly, the latter series is printed on the book’s front cover, thus constituting an alternative beginning.

In Nude Animal Cigar, the connecting thread is the process of sepia toning. Once applied to analogue prints to enhance their durability, sepia toning is now but one of many tools in Photoshop used for aesthetic and nostalgic effect. “The effect has been successful and absurd,” says Kooiker. “The strange thing is that it has been barely spoken about [in reviews of his project]. I don’t think people note the irony.”

Kooiker likes to play with cliché and stereotypes, right up to the edge of the banal; and now he has taken on sepia, he promises to never use it again. But for him, taking a photograph is just the start, creating the raw material that he will then process and treat on-screen and on the large inkjet printer in his studio. “In the first phase I am a photographer; in the second phase an artist,” he says.

The two sides to his work don’t always come together at the same time – sometimes Kooiker’s photographs quietly disappear into his immense image archive. But this archive is a living repository, which allows him to make exciting rediscoveries sometimes years after the event. Many of the figure studies in Nude Animal Cigar lay dormant in this archive, for example, before finding new life through being ‘sepiafied’ and combined with images of two rather different subjects, whereas the pictures of cigars and animals were all taken and processed specially for the exhibition.

“The nude photos come from my archive, mostly of the past five years,” he says. “Many are more classical nude poses that hadn’t found a place yet in my output.”

Kooiker doesn’t want to photograph ‘perfect nudes’ – the kind of pictures familiar from our mass media – so he contacts plus-size models via amateur modelling sites, then enters into a professional relationship by paying them well. Often photographing them draped across a table or a chair and avoiding showing their heads, Kooiker also shows them wearing classic high heeled shoes to avoid the impression of post-mortem photography.

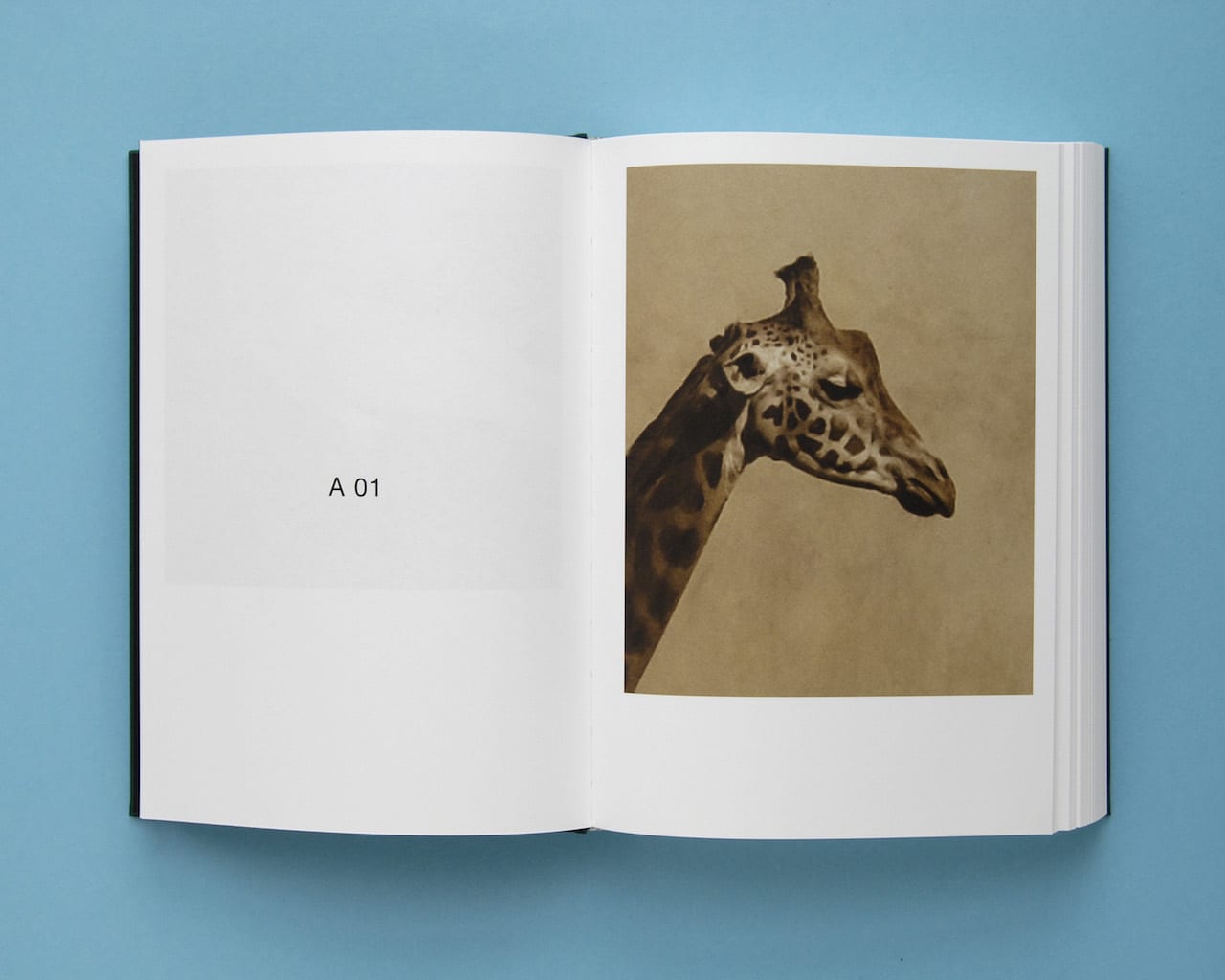

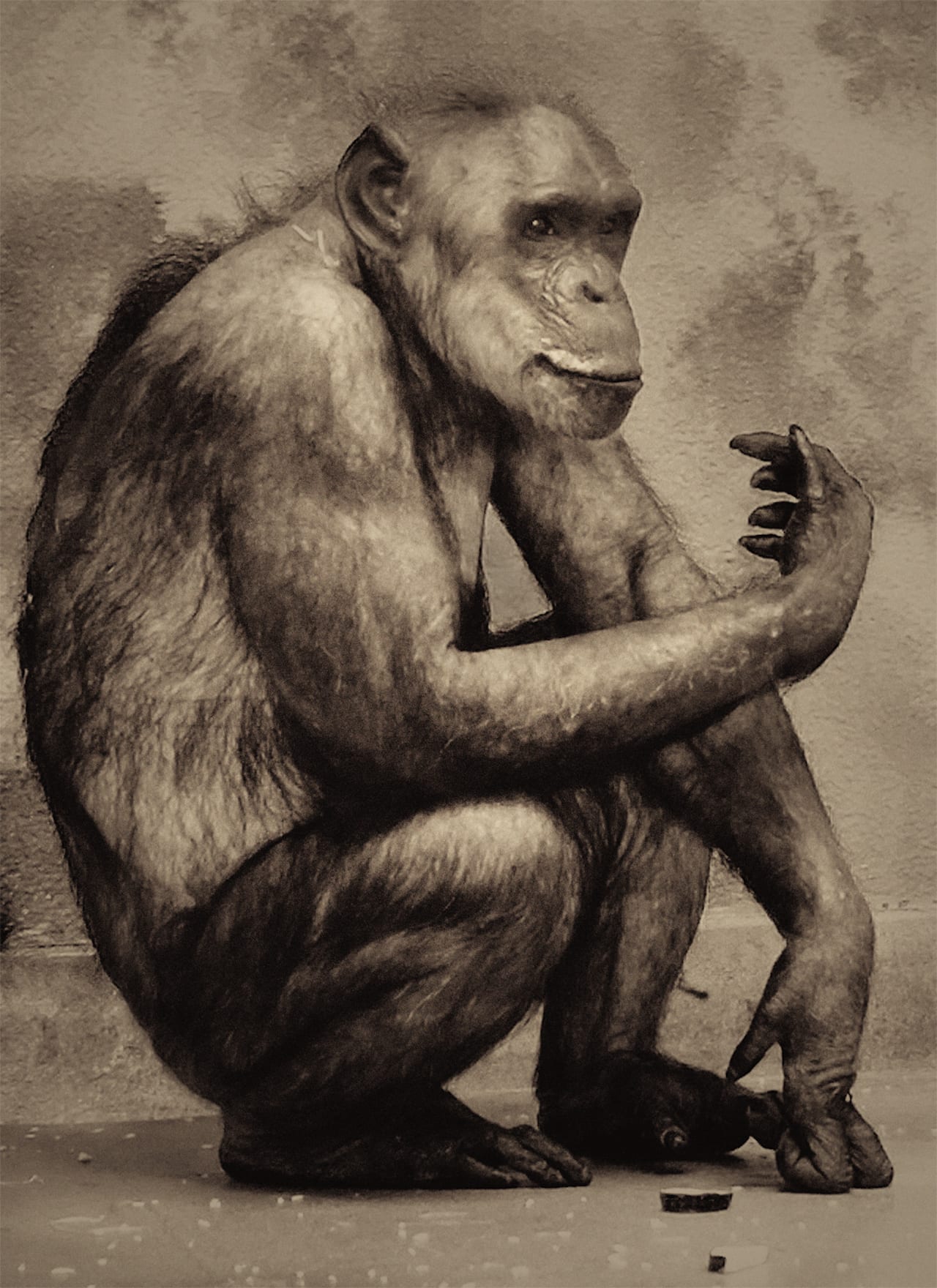

In Nude Animal Cigar, the nudes are shown in a variety of compositions and styles, resembling different photographic traditions, but it is only the animals that ‘look’ at us. They were photographed in captivity, at the various zoos across Europe that Kooiker has visited with his daughter. The cigar photographs have the same kind of jocular compositional inventiveness as the nudes, and display a similarly sculptural texture and quality. In effect, they are a series of studies of form, exhausting the possibilities of how many compositions can be made with cigars, so Kooiker is playing with how to reach maximum effect with minimal input.

In fact, the words ‘play’ and ‘playful’ often come up in our conversation, after which a slightly hesitant Kooiker explains: “What remains important is to stay honest and make work that has credibility. If your work is fake or overblown, you will quickly be unmasked.”

It’s a fine line between the kitsch and the controlled, the playful and the serious, and it’s part of what makes Kooiker’s work so unsettling. Van Zoetendaal hit the nail on the head in his speech at the opening of Nude Animal Cigar in the Fotomuseum Den Haag, stating that he often doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry at Kooiker’s work: “This is exactly the attitude required in approaching Paul’s work.

“One needs to study it. Save yourself from prejudice. Open up and ‘decondition’ your mind. You may think it’s beautiful or ugly, but let me clearly warn you [of ] the chances of misunderstanding.”

In what has become a famous line from the sixth canto of his poetic novel, Les Chants de Maldoror, published in 1869, Comte de Lautréamont describes a young boy “as beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella”. This line was held dear by the Parisian Surrealists in the 1920s, inspired by Lautréamont’s suggested links between seemingly unrelated realities. In Nude Animal Cigar, Kooiker plays just such a game. His photographs reference a variety of styles, from Pictorialism and Surrealism to vintage amateur snaps and the kind of mediocre images of animals you find in commercial illustrated picture books.

And yet they’re more than the sum of their parts, eerily reminiscent of earlier times, but unmistakably contemporary too. The nudes, animals and cigars have as little to do with each other as that beautiful chance meeting on Kooiker’s dissecting table of camera, computer and printer. The book is a vast shaggy dog story, yet it’s deadly serious, asserting his voice and idiosyncratic view of the world.

As he says: “I am the link, because I have been obsessed with these themes for more than 20 years and brought them together for this project.”

www.paulkooiker.com This article was first published in the May 2015 issue of BJP