1854 was a big year for photography. Kodak founder George Eastman was born, and the first issue of British Journal of Photography was published in Liverpool. Since then, the magazine has undergone several evolutions, rejigging its format from a weekly trade journal to a monthly glossy, and changing its name several times along the way. The magazine’s content has also continued to shift. With roots in scientific journals, British Journal of Photography has now changed course and grown into an art and documentary photography magazine, focused on the cutting edge of editorial and commercial practices. However, looking to the past, its most instantly noticeable transformation is its change in design.

Staying alive for 164 years is a formidable achievement, but perhaps the key to our long life is our capacity for change. The redesigns of the magazine have always reflected its changing direction and willingness to adapt to the times, and they have carried us through right up to the present day. Here are some of British Journal of Photography’s most drastic changes.

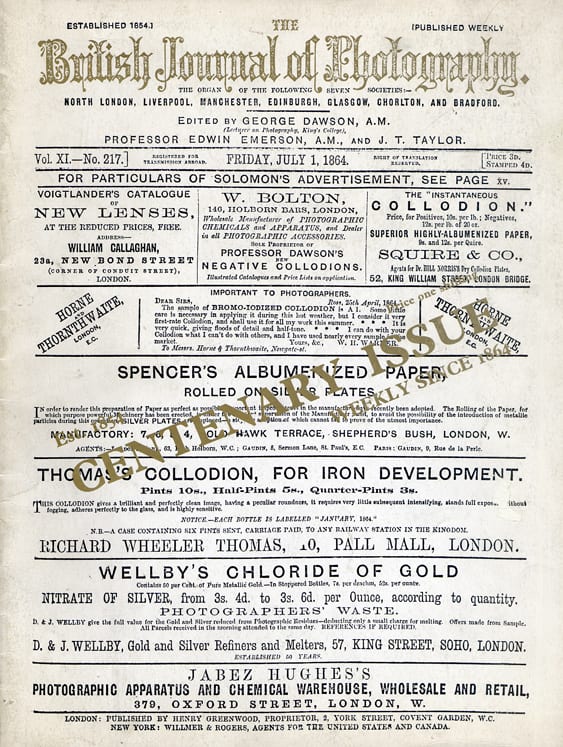

1864

This centenary edition is a replica of one of British Journal of Photography’s earliest formats. As you can see, it looks more like a modern broadsheet than a typical magazine. Primarily due to the lack of technology, images are noticeably absent from the front cover, and many of the bulletins are advertisements for collodion suppliers. Collodion was a substance used on glass photographic plates. It reduced the exposure time necessary for making an image, and was relatively grainless and colourless, allowing for one of the first high-quality duplication processes, or negatives.

The golden age of printing and illustration began in America in 1880, and equalled rapid advances in printing technology. This spread over to the UK soon after, so until then, all front covers would have looked something like the image above.

This is also the year that British Journal of Photography became a weekly publication. Prior to 1864, it was released monthly until 1857, and then fortnightly. Writers during this period included Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

1933

This 1933 cover has less writing on it than its 1864 counterpart, but little else has changed. Described as ‘the recognised organ of professional and amateur photographers’, British Journal of Photography was still positioned as a weekly trade journal, advertising and recommending photographic products, and charting the growth of the medium and its surrounding technology.

This is a perfect example of an early edition of the magazine, detailing experiments and discoveries of photography societies across the country, alongside articles about new equipment and processes. It wasn’t until photography began to become accepted as an art form that the magazine started to feature photographers and their work.

During the interwar period, British Journal of Photography was given special compensation so it could continue during both world wars. Unbelievably, it maintained weekly production throughout the first and second world wars, racking up a huge number of issues. We are currently running issue number 7874.

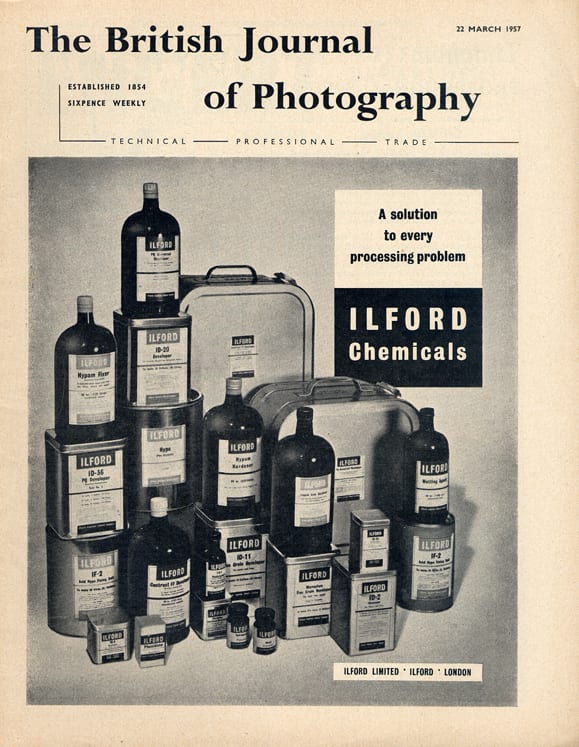

1957

The first clear difference here is that the title is transformed, and has been given a modern update. The cover is also starting to become more familiar to those we see today, although the image is still an advertisement. This advert is for Ilford chemicals, which has continued to sell photographic materials for more than 60 years.

By the 1950s, photography was widely accepted as both a professional and artistic pursuit. In response, British Journal of Photography began to appeal more to the business and commercial side of the industry. Its cover is emblazoned with the words ‘technical’, ‘professional’, and ‘trade’ – the content had not yet shifted so much into the artistic practice.

Notably, 1957 was the year that the first digital photographs were created, by a team led by Russell A. Kirsch at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Kirsch created a wirephoto drum scanner to transfer alphanumeric characters, diagrams, photographs and other graphics, into digital computer memory. One of the first photographs scanned was of Kirsch’s six-month old son Walden.

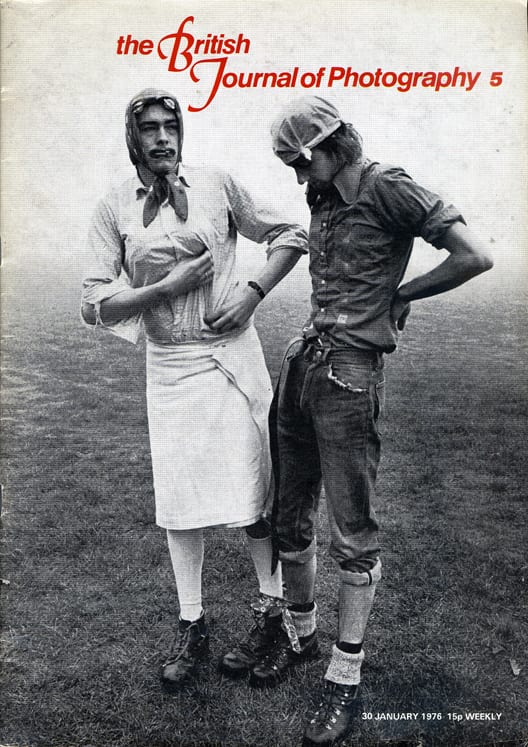

1976

This issue is starting to look more like the current publication. Published in 1976, during the heyday of professional photography that emerged between 1960 and 1980, this January 1976 issue was released as a weekly installment.

The 1970s were the years of gritty social documentary photography. Following the example set by Diane Arbus, Larry Clark and Nan Goldin had begun to document their alternative lifestyles, building a new genre of direct, unflinching photography that continued to establish itself towards the end of the century.

This cover image is by photographer Homer Sykes, whose 1970s archive documents a country seething with class conflict. His work perfectly embodies the social commentary photography trend that gripped the industry at the time.

2000

Since the 1990s, British Journal of Photography has focused more on the creative side of things. There was rapid growth in photographic education, and photography as an art form became mainstream from the 1990s onwards. In reaction, the magazine continued to change its content and design.

Billed as ‘The Professional’s Weekly’, BJP’s focus was broad at the turn of this century, as you can see from the contents of its 2000 edition. Fashion, collecting and erotica all featured as part of this issue, which was released to celebrate 150 years of photography. This ‘special millennium bumper souvenir issue’ also employs all of the common tropes of mainstream nineties and noughties publishing.

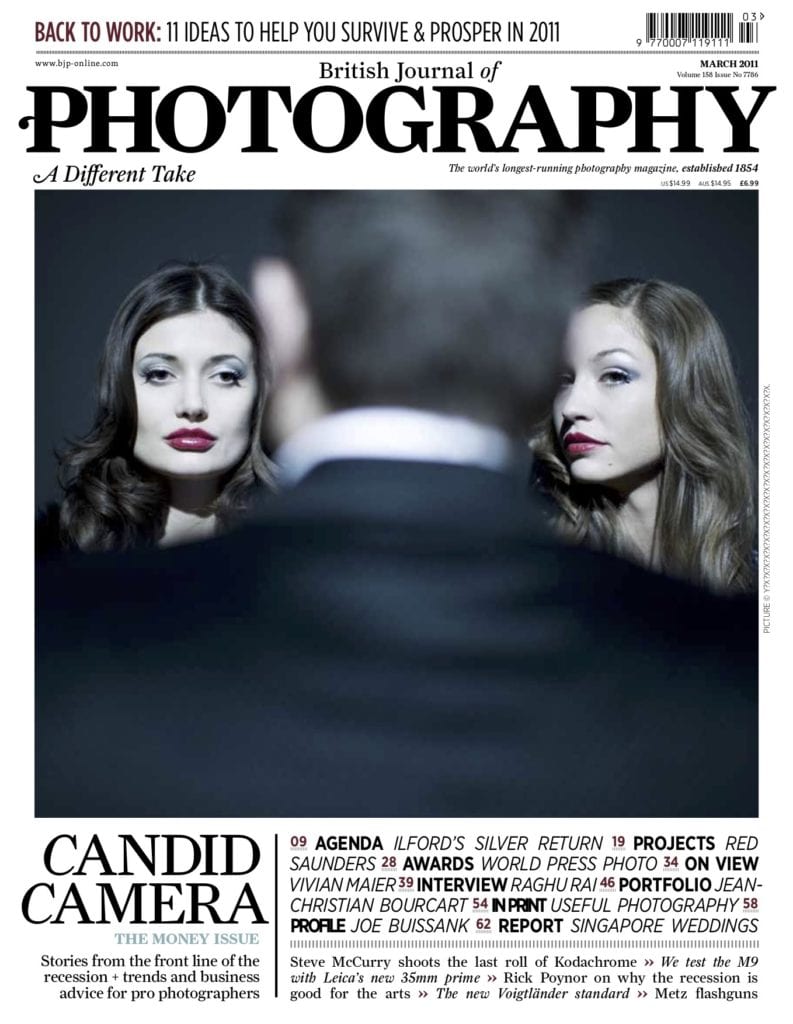

2011

This new format came about in 2010. The brief? Classic with a twist. In 2010, British Journal of Photography was repositioned as a premium monthly, aiming to make more of a bang on newsstands, and drawing inspiration from artsy independent magazines.

The change in design also signalled a change in readership, appealing to a pool of creative professionals, as opposed to just camera buyers. This doesn’t mean the original readership was abandoned – the magazine still published product profiles and in-depth reviews, but the articles began to mirror today’s content, with long-form editorials and interviews taking centre-stage.

Interestingly, one of the cover lines here is ‘Stories from the front line of the recession’. From 2011, the magazine industry rapidly began to fold, as content moved online and away from the printed page. In 2011 alone, 152 magazines ceased publication, continuing in the same way each year. Remarkably, it is the independent magazine sector that has continued to prevail, much more so than commercial, mainstream publications. Moving towards a more arty, independent form at this time was a bold, but retrospectively necessary move, for British Journal of Photography.

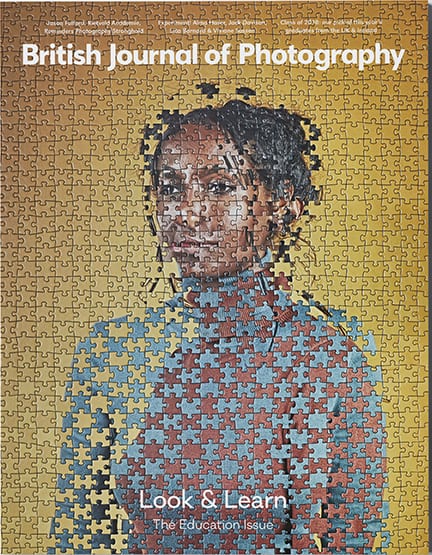

2018

This new design takes on the form of an evolved academic journal, but strips itself back, removing much of the text that was on the cover before. One of the main reasons for this 2015 redesign was to separate the British Journal of Photography from camera magazines, like those it is often positioned next to in magazine shops and stockists. Now confident in its role as an art and documentary photography magazine, BJP wanted to distance itself from product-focused titles. This final redesign brings the magazine forward to the publication we know and love today.

British Journal of Photography remains dedicated to covering the best of photography, spotlighting new talent and established practitioners, along with new equipment and technology. Subscribe to BJP today to find out about the most inspiring and innovative photography before anyone else.