“It may seem like a provocation, but I am not particularly interested in architecture – at least not in that of great architects and cult buildings,” says Eric Tabuchi. “I’m interested in what humans build, whether for shelter, work, recreation or worship.

“Basically, what has captivated me for 20 years is the vast domain of anonymous architecture, which is the daily environment of most of the inhabitants of this planet, and which we do not look at it so much. It appears to us without any real quality.”

Born in 1959, Tabuchi “came to photography late”, after a youth that included a spell in the French new wave pop group Luna Parker. Studying sociology he came across August Sander’s work, and “very quickly had the intuition that I could try to transpose his project by photographing not people, but rather what they build”.

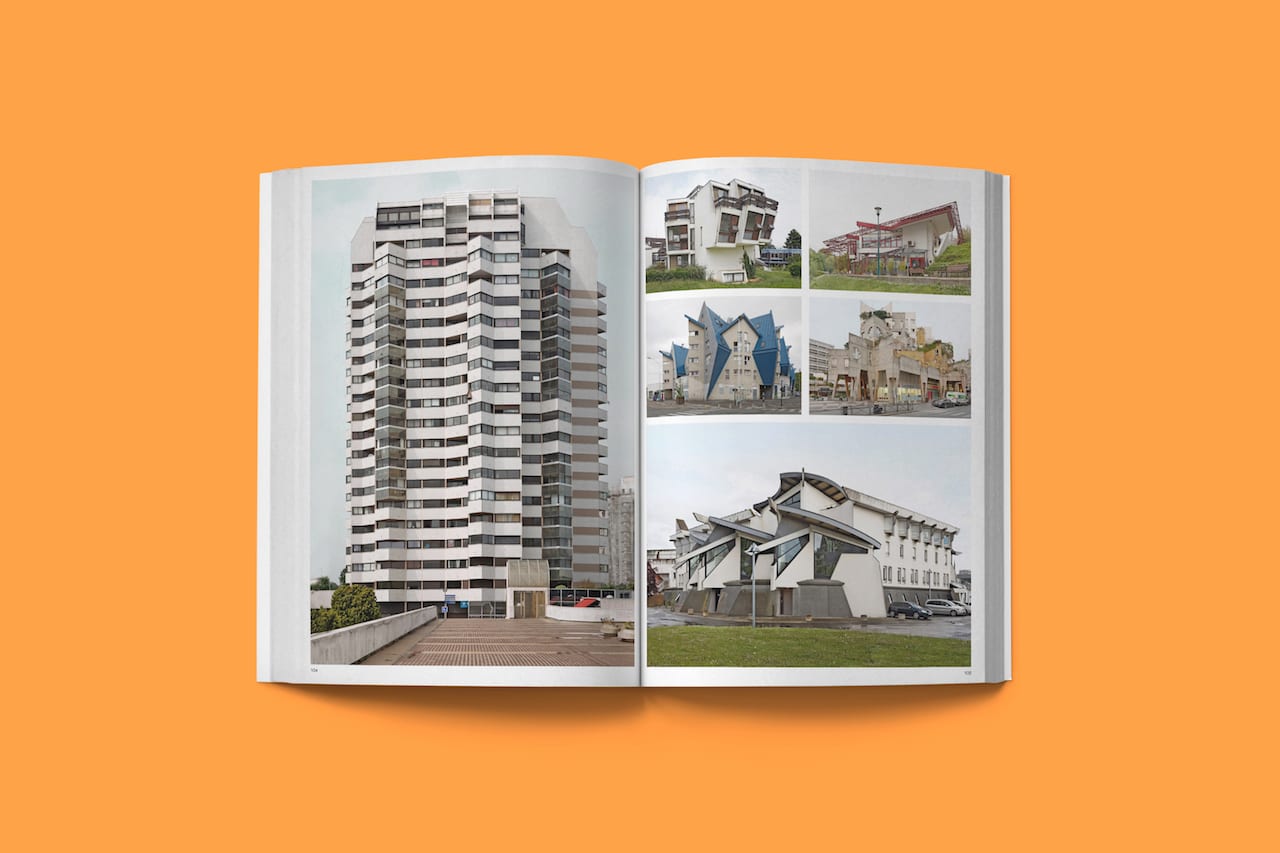

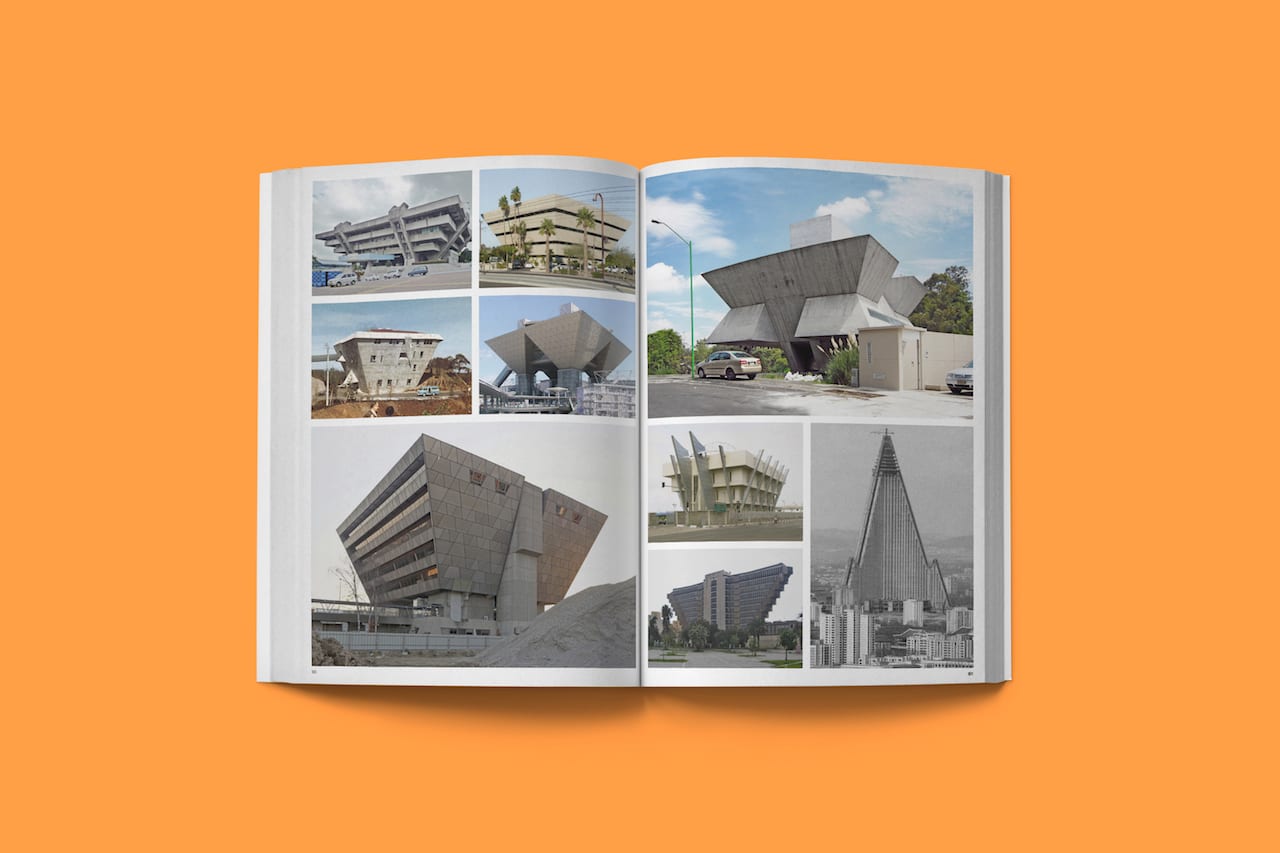

Fast-forward to 2018 and he’s built a whole career on his images of the built environment, taking photographs in which the constructions “are always placed in the centre and relatively isolated, so that they seem magnified”. These images are substitutional portraits, he says, which if seen all together and side by side “would be a portrait of a society, in all its diversity”.

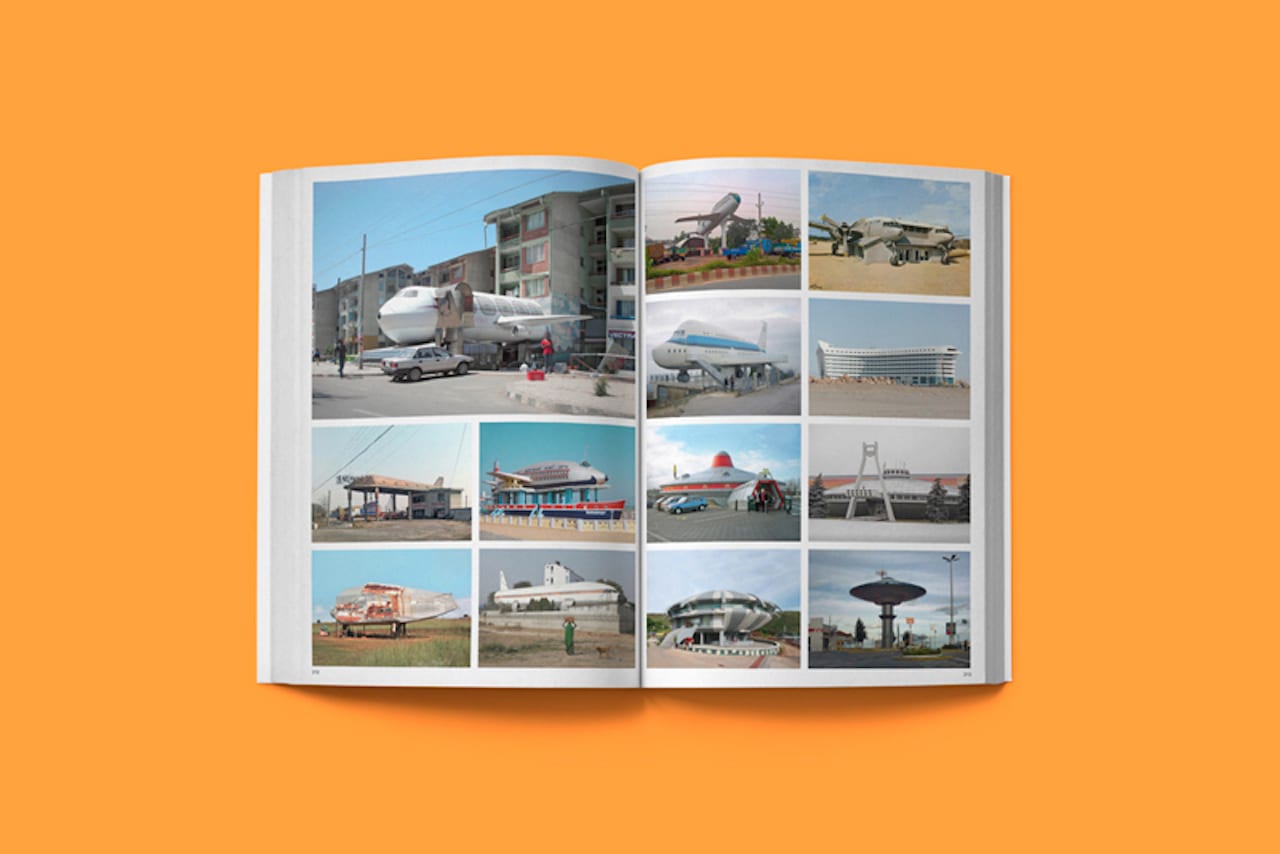

And in fact Tabuchi’s images are designed to be seen side-by-side because, inspired by Ed Ruscha’s Twenty-four Gasoline Stations, he always works in series. In fact he’s even produced a direct homages to Ruscha, Twenty-six Recycled Gasoline Stations and Another 26 Abandoned Gasoline Stations – but whether he’s looking at petrol stations or small-town Chinese restaurants, his projects are always typologies, which take a certain subject and collect numerous examples of it.

For him, this approach lends a certain sense of distance, and the typology “is to photography what the dictionary would be to poetry – an attempt to objectify the look and definition of objects”. [Interestingly Luna Parker’s biggest hit, Tes stats d’ames Eric, also references dictionaries, and visiting moods one by one in alphabetical order]. It is a “refusal of a certain exhibitionism”, he says, but it’s been highly successful nonetheless, and Tabuchi has had solo shows around the world – including in the Palais de Tokyo in Paris and the HKU/Shanghai Study Centre. His last book, Atlas of Forms, was one of Libération’s top ten photobooks of 2017.

Atlas of Forms was a new departure for Tabuchi, though, as it uses images found online rather than ones he’s shot himself. Initially forced on him due to ill-health, he spent many months online, travelling on the internet “a bit like I used to in the real world, that is to say by letting myself be guided by chance, and the intuition of the moment”.

Starting near to home then expanding onto sites in languages he didn’t understand, such as Russian or Chinese, he “explored the virtual territory” and soon he found himself collecting images just as he would have done on real world travels. As in his own work, he focused in on images in which the building was centred and entirely contained in the frame, but in looking for other photographers’ work he focused on vernacular images, taken by tourists or building companies rather than by celebrated names.

“Retouching the parallaxes, the colours and the contrasts”, he built up a collection that “seemed to belong to a common source”, a collection that soon swelled into a “teeming mass” of images. Slightly overwhelmed, and keen to find a way of categorising and classifying the photographs, he hit upon the idea of building a website – on which the images would be tagged with a short list of characteristics, and therefore searchable by them too.

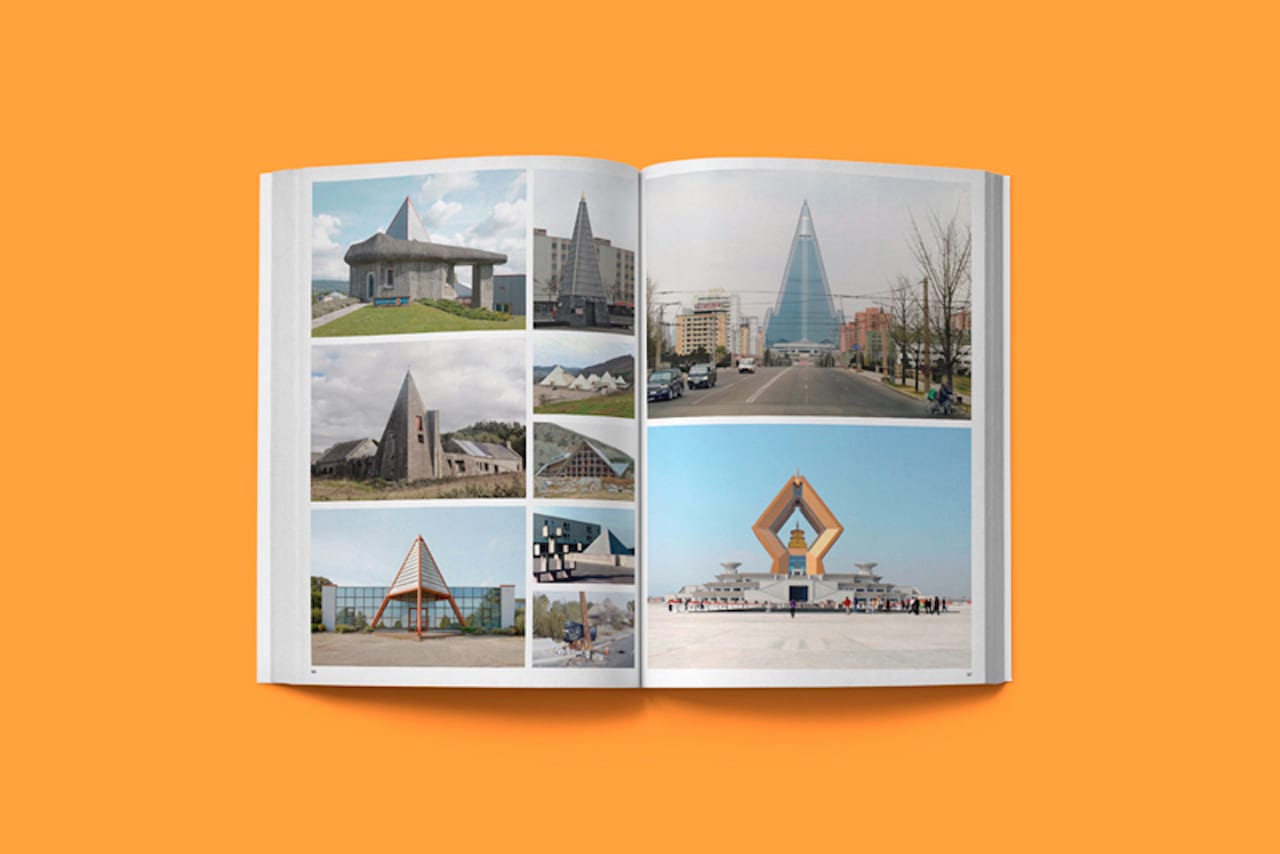

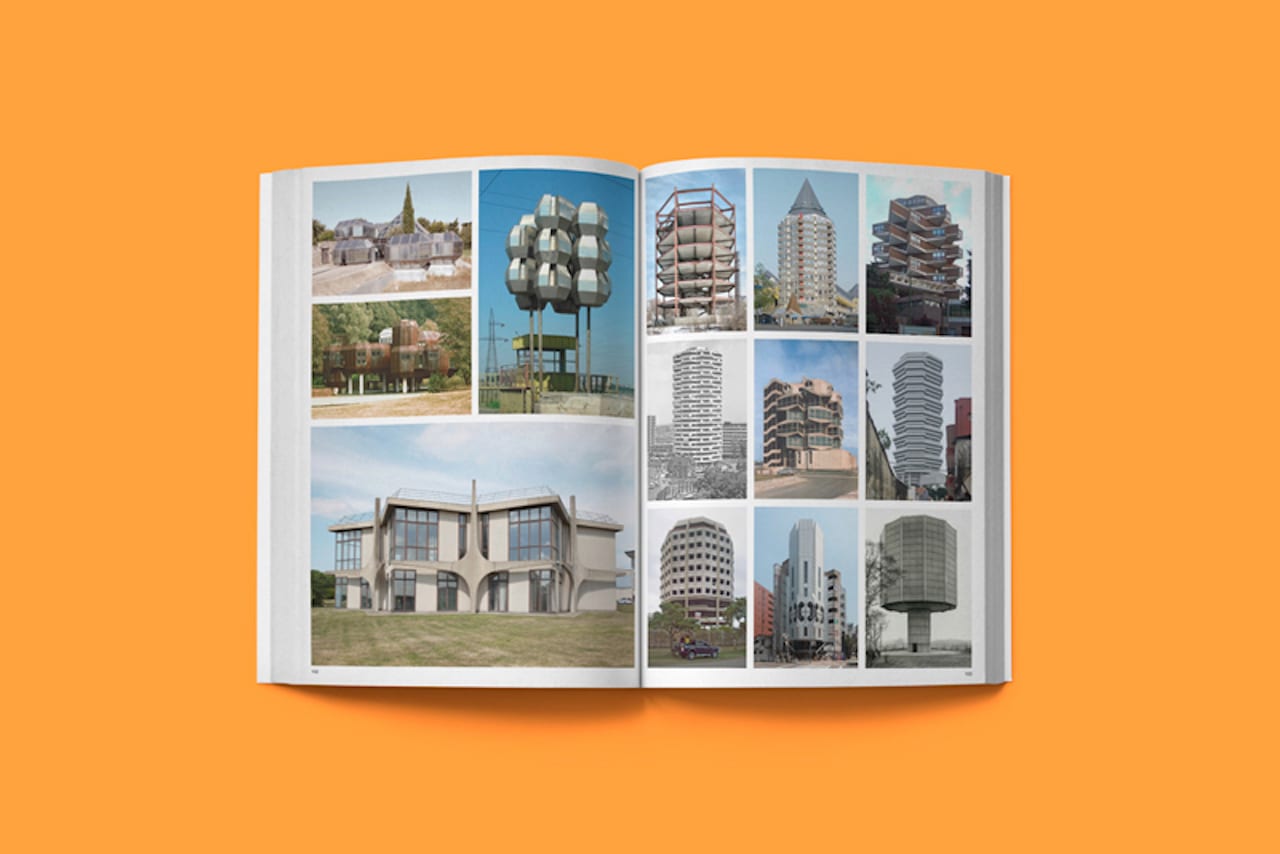

“Very quickly the principle of a reduced number of geometric criteria appeared to me,” he tells BJP, and the finished result has an ingenious four-category format – users can search by shape (‘circle’, ‘square’, ‘triangle’ or ‘polygon’), but then add further criteria, such as ‘small’ or ‘massive’, or ‘construction’, ‘completed’, or ‘decay’, to further slim down the results.

Tabuchi kept “feeding it new images” but considered the project finished when the website was done, satisfied he had found a useful tool “for archiving and sharing the thousands of images I had gleaned during this period”. Then he met Benjamin Diguerher, the director of Poursuite, and decided to make a book – a publication that would represent “the materialisation of the internet version”.

The resulting photobook includes nearly 1500 images, classified according to shape or to current state [construction site, completed, abandoned or in ruins] but, unusually, containing absolutely no text other than the front cover title. “It seemed to me that the interest of these images did not reside so much in the answer to the obvious questions – ‘where, when, what, how’ – but, more simply, in the fascinating diversity of shapes they showed,” he explains.

“From that moment, I chose to make a totally silent book in terms of conventional information. A book in which all forms, whether trivial or sacred, humble or noble, majestic or dilapidated, coexist on equal terms.”

For Tabuchi this choice, “radical in a way”, offers another way to understand the world to the many scholarly works on architecture. “Thus in a childlike way, a police station in Peru, a residential tower in Ukraine, a blockhouse in Normandy or a shacks in Thailand, all these constructions are rid of the prejudices that make us very easily located,” he says.

“They are no longer things in a hierarchy of the beautiful and ugly, the respectable and the despicable, they have an equal status, as much as possible. What is manifest here is the multitude, the variety, the diversity and not the position in a scale of taste or consideration.”

In this way, he adds, Atlas of Forms aims “shake a little the certainty we have about the world around us” – and also to resist the internet’s tendency to slim down our search results. He’s always struck by how the billions of images available online end up turning into “the eternal photos of iconic buildings from brutalist blogs” in search results, he says; by contrast, he wanted to show “how much what humans build is as diverse as humans themselves”.

And, he adds, he wanted to show how the life cycle of buildings also echoes the human experience – thus starting his book with spherical buildings under construction “as if it were the creation of the universe”, and ending on a blockhouse of the Atlantic Wall that’s fallen off a cliff, “huge monolith of concrete delivered to tidal erosion”. “Between these two extremes, there are all the stages – from the construction to the demolition or the abandonment, from the appearance to the disappearance, which tell the incredible vitality but also the vanity that there is in the ambition human to leave, by the act of building, a lasting trace,” he explains.

“Definitely, what I want on a very small scale is that the book shakes a little the certainty we have about the world around us. It is like a carnival of forms.”

Atlas of Forms is published by Poursuite, priced €38 www.poursuite-editions.org www.erictabuchi.net