He is stood waiting for me, his front door open, a jungle-like front garden and broken stone pathway separating us. Visible from the street, in this quiet, rundown corner of Leeds, I can see frame upon frame of photographs stacked and piled around him. Peter Mitchell leads me through to his front room, a room evidently used as something of a workshop, piled high with miscellany, across the walls, on shelves, bursting from drawers.

He moves a stack of precious belongings from a chair in the corner, then plonks it in the middle of the room, gesturing me to sit. I carefully manoeuvre myself through the clutter, afraid to disturb anything. To my left lies a beautiful photograph of old, blackened homes in the Don Valley, the industrial centre of my hometown in nearby Sheffield, now the home of Meadowhall, one of the largest shopping malls in Europe. To my right is a group portrait of kids playing in the shadow of Park Hill, Sheffield’s vast council estate.

Mitchell was busy framing both for an exhibition at Impressions Gallery in neighbouring Bradford when I turned up. For more than 40 years, this kindly, funny man, now in his seventies, has been quietly making photographs of his surrounding environment in the north of England. He’s done so with the minimum of fuss, without any fanfare or desire for the public eye. And the residue of that life is all here, surrounding me.

Now he’s finally been awarded his first major survey show, A New Refutation of the Viking 4 Space Mission, opening a week before the closing of his exhibition at Rencontres d’Arles. A recluse he may be, but Mitchell is also extremely influential. “It’s a mystery to me,” he says with a shrug, when I ask him how he’s achieved such a feat. “But there you go.”

Our geographical setting makes such a trove even more unlikely. Mitchell lives on Spencer Place in the north-west of Leeds. A couple of hundred meters away lies Potternewton Park, an undulating, bucolic urban space of grass and trees and play areas, home to the annual Chapeltown Carnival and a 30-minute walk from Leeds city centre. If this were a suburb in London, these large Victorian and Georgian houses would sell for well over a million. But in this neck of the woods, you can own a six-bedroom period terrace house for a little over £150,000.

It’s a sunny day and, but for an occasional teenager sloping around on a bike, the streets are quiet. But in the early noughties this tree-lined, suburban avenue was a notorious red-light district, populated every night by sex workers leading their clients down the dark alleys that pockmark the mile-long street. Drug dealers moved in and crime inevitably followed, with knifings, shootings and gang scraps flaring up on the street corners.

Thirteen years ago a concerted campaign by local residents forced council and police to announce a “clampdown”, and the situation improved, without in any way becoming resolved. In the taxi from the city’s main train station, my driver asks again and again why I would come all the way from London to visit Spencer Place, seemingly unwilling to believe a major artist could live in its midst.

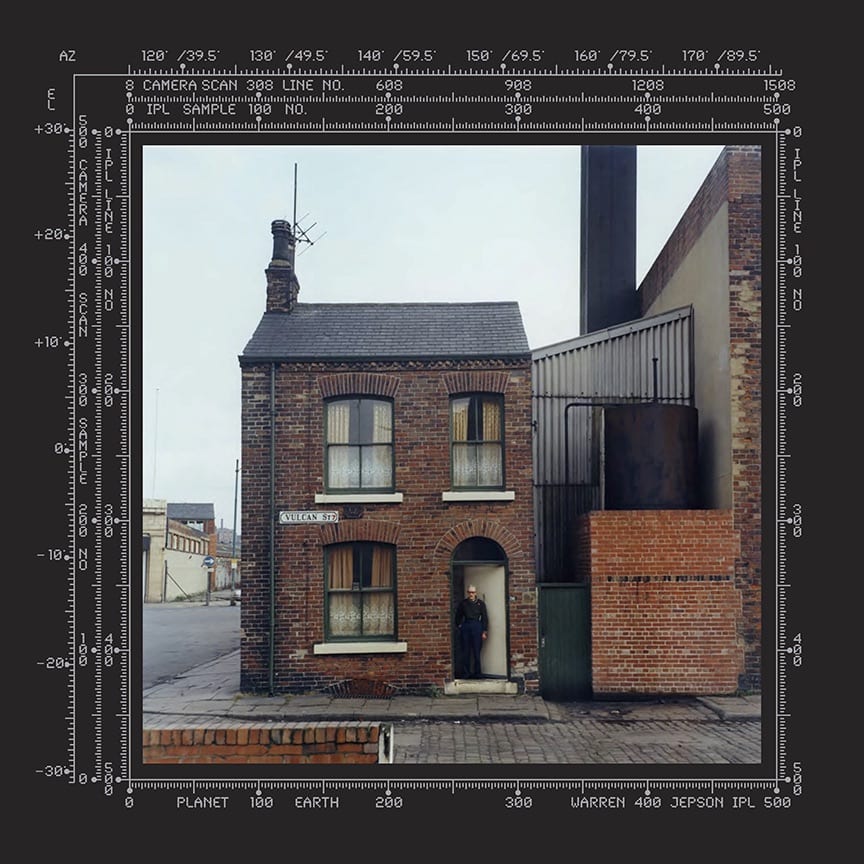

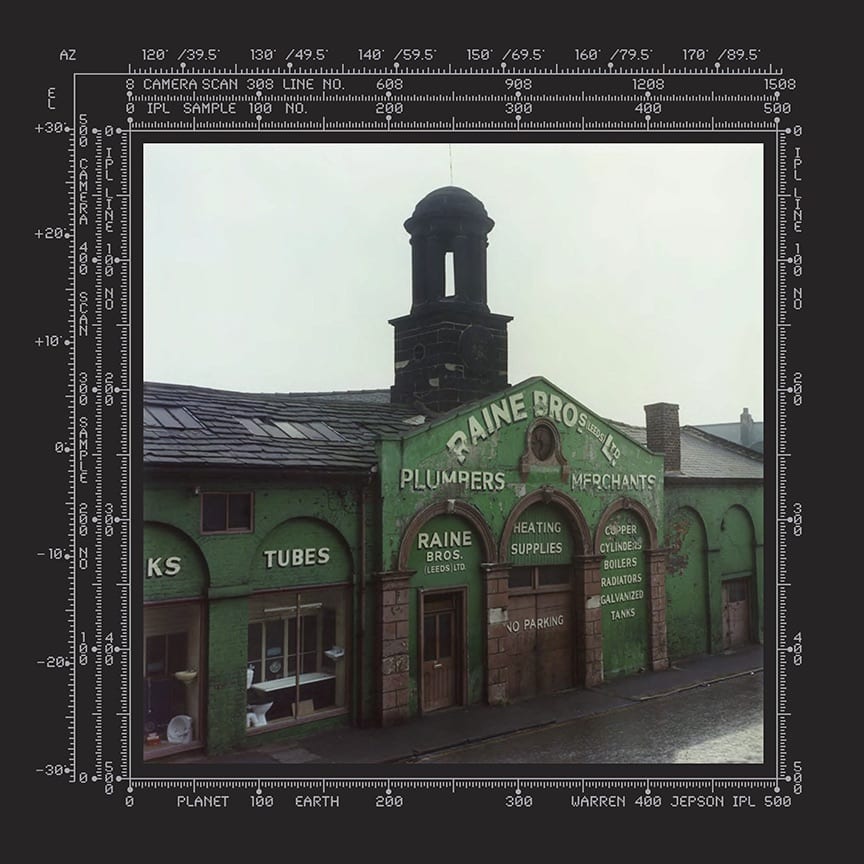

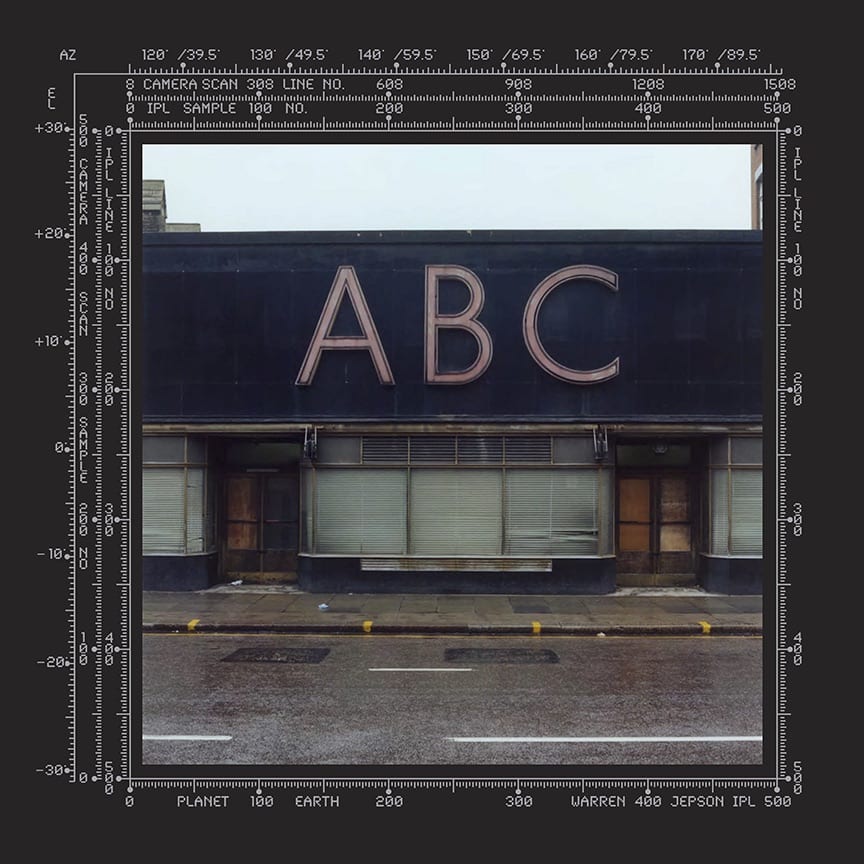

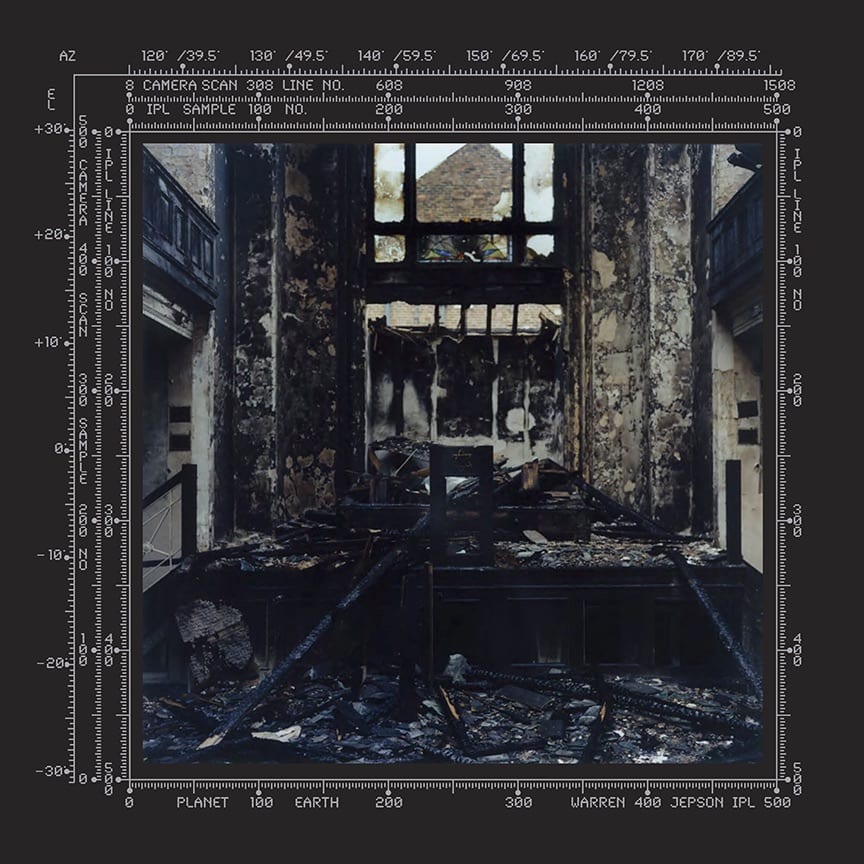

Mitchell has lived and worked here since 1972, having first turned up to visit friends squatting in a large house in Headingley. One rainy day he stopped by an estate agent and ended up renting this rather grand old place for £2.45 a week. He went on to buy it for less than £2000. He’s used Spencer Place as a base to photograph north England ever since, making carefully observed studies of factories and pubs, small brick homes dwarfed by large modernist water cooling towers and single red phone boxes serving great, newly built Brutalist council estates.

Are they expressions of working class life, I ask him, and the answer is yes and no. “My father was very working class. He was a unionist, an outspoken socialist,” he says. “So I’ve always felt working class while not living a very typical working class life. But I don’t see my photographs as expressions of working class life; more impressions of what this city was like when I first moved here.”

His love of Leeds is evident, even as he, in typical northern style, rebuffs hyperbole. “I could see the 21st century beginning to happen to Leeds, all the way back then,” he says. “Leeds was an eye-opener – thousands of back-to-back houses, factories and factories and factories, with all the smart stuff in a tiny circle in the city centre. It felt like the centre of the world to me.”

Born in Manchester, Mitchell left school at 16 and moved to Hampstead in north London to train as a draughtsman in the Ministry of Housing and Local Government in Whitehall. Quickly tiring of it, he went on to study typography and graphic design at Hornsey College of Art before moving to Leeds in 1972. Settled in Spencer Place, he worked as a truck driver for Sunco and began photographing the city on his rounds for his own enjoyment.

He would stick a stepladder in the back of the truck, using the high vantage point the steps afforded him to capture images of the city – the factories and their workers, the pubs and small shop owners. Each was formally arranged and carefully composed, with a natural eye for shape, colour and composition. In his basement, he set up as a fine art silkscreen printmaker and, with the help of a darkroom in the city centre, hand-processed his own photographs. But it remained an amateur pursuit, in the best sense of the word.

“I’ve had loads of jobs, but I’ve never made any money out of photography,” he says. “This year, it looks like I might make a bit of money,” he continues, adding that Phillips will soon be putting his photography up for auction. “But who knows? I could be getting ahead of myself.”

Why does he think that’s the case, I ask? How has he managed to evade the limelight for so long? “I’ve got no ambition. I never really know what I’m doing, but then I always know where I am, I guess.”

Mitchell had his first solo exhibition, titled An Impression of the Yorkshire City of Leeds, at the Education Gallery in the nearby City Art Gallery in 1975. But it was his first solo exhibition in a photography gallery, the first showing of A New Refutation of the Viking 4 Space Mission at Impressions Gallery (in its original York location) in 1979 that established his name on Britain’s nascent photo scene.

“There was no art photography at all at that time,” Mitchell remembers. “There were only camera clubs, and they were only ever interested in photographing a flower or a landscape, with a lot of detail in the caption of what camera was used, how it was processed. I just didn’t find them interesting.”

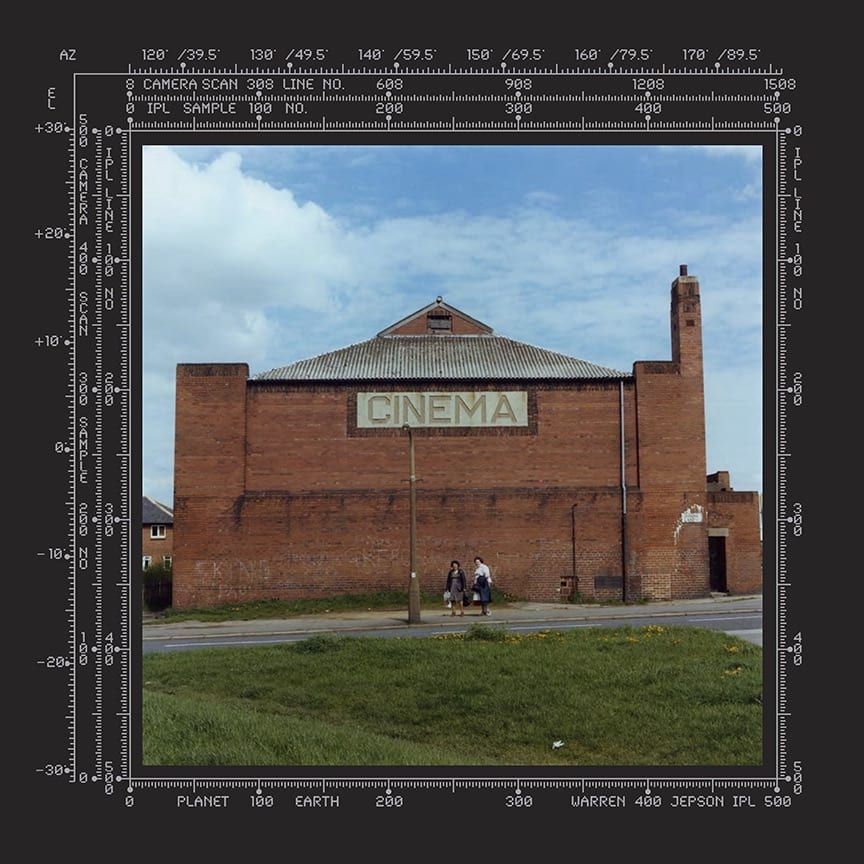

It was the first colour show at a British photography gallery by a British photographer, but Mitchell didn’t know it and played up the humour by giving his images long, literary captions. In the mid-1970s, the stationary Viking Landers were the first man-made crafts to land on Mars, allowing us to see the red planet’s dusty landscapes for the first time. Today, not a single trace remains of either Viking Landers 3 and 4. And so conspiracy theories started to surface, that somehow life on Mars had co-opted the landers and used them to chart their own course back to Earth, and that maybe such aliens were seeing our landscapes for the first time, marvelling at them back home in a mirror image.

Mitchell is still delighted by such an idea. He mounted his images on space charts, as if aliens from Mars had crash-landed in Leeds and were trying to figure the strange place out. The show featured photos and portraits, taken in Leeds, showing traditional shops and factories, printed in colour and hand-processed by Mitchell himself. “This show was so far ahead of its time,” says Martin Parr, who saw the show at the time, “that no one knew exactly what to say or how to react, apart from with total bewilderment.”

In retrospect, it’s clear that Mitchell was a pioneer, perhaps the first photographer to use colour in his documentary photography work in Britain, and to engage in such a high-concept documentary narrative. Parr, along with Paul Graham, urged him to move to London to find an audience for his photographs, and he’s remained a vocal supporter ever since.

“Martin Parr has saved me from total obscurity,” Mitchell says with a laugh. “But then I rather like the business of being a hermit, a recluse in the north. It’s not quite a badge of honour, but it’s getting that way. When I went to photography exhibitions, I’ll admit I would go slightly boastfully, with a bit of an aggressive tone, rather than an open mind. I’ve always been that way.”

I wonder how he’ll tackle his newfound emergence from obscurity: feted in Arles and firmly in the spotlight closer to home, with his retrospective in Bradford, where he will be responsible for everything from hand- processing the original negatives in a dark room to painting the walls. “I don’t like the word retrospective,” he says. “That’s for dead people. I’m a long way from that yet.”

And so I leave him, walking down Spencer Place as he busies himself again with the framing of his pictures, working in solitude, doing it for the hell of it, and loving every minute.

A New Refutation of the Viking 4 Space Mission is on show at Belfast Exposed from 12 January – 24 February www.belfastexposed.org