Wim Wenders was given a new Polaroid camera yesterday. It was a gift. He doesn’t plan on using it.

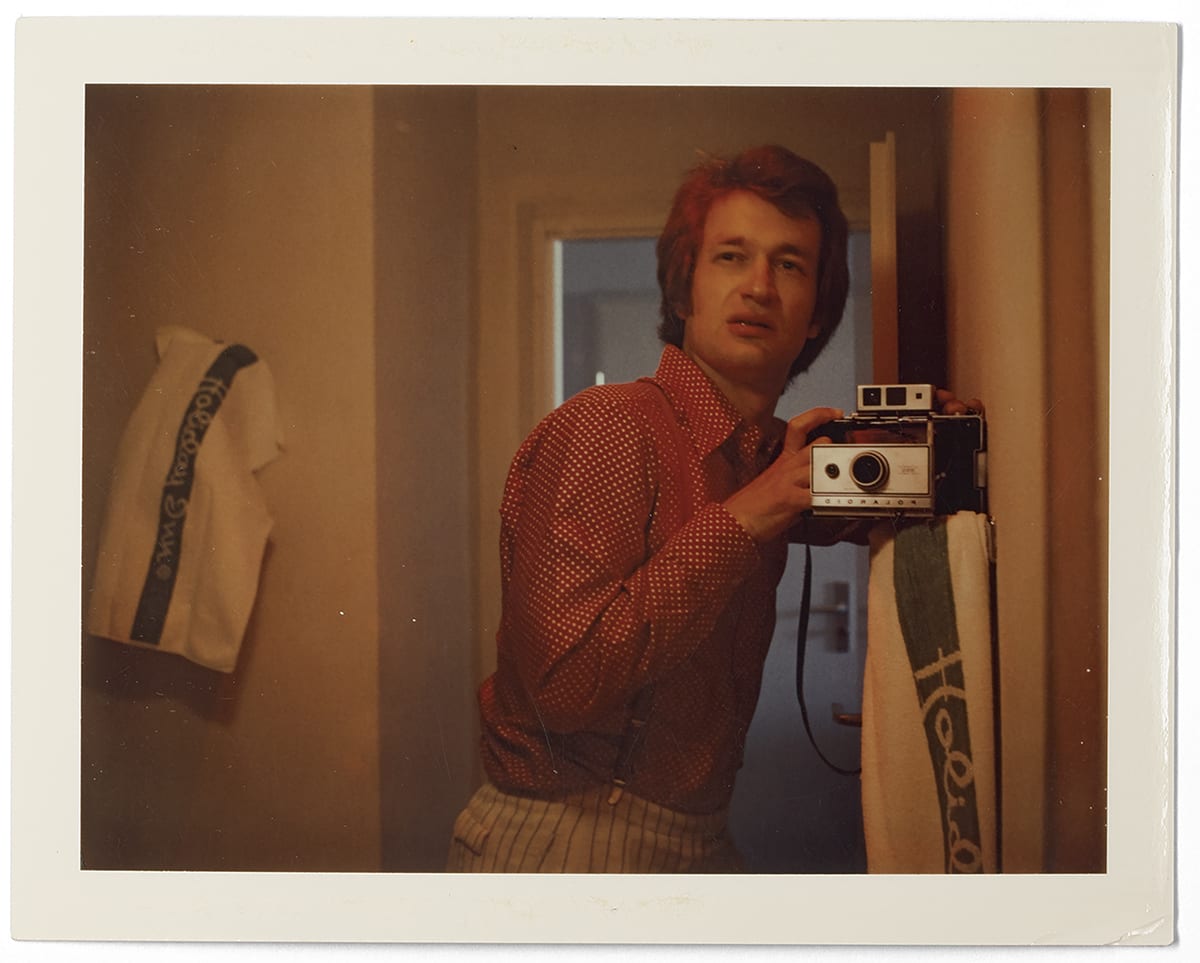

“It’s funny,” he says quietly, before pausing to carefully frame what he wants to say next. “I picked up this new One Step 2 camera and instantly everything came back to me. My hands remembered how to hold it and how to use it. But it was definitely a nostalgic act, and that felt a bit strange. When I took all these thousands of Polaroids between the late 1960s and early 80s it was anything but nostalgic. At the time, that was modernity.”

While in recent years Wenders has become almost equally as recognisable as a photographer as a director, with his large-format landscape photographs being exhibited in galleries around the world, he hasn’t taken a Polaroid in years. It might seem strange then that the German filmmaker behind such works as the Palme d’Or-winning Paris, Texas (1984), Wings of Desire (1987), and the Academy Award-nominated documentary about Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado, The Salt of the Earth (2014), has launched an exhibition featuring over 250 of his old Polaroids, most of which were captured on his beloved SX-70.

“At first I was worried that these old Polaroids might not be interesting for anyone else,” he explains. “That they might only be nice for me to look back to. But the more I looked at them the more I realised that there was something there worth sharing. But I would need to create the context for the viewers, so I wrote these stories [to go alongside them].

“Polaroids remind us of an innocence, of a different attitude toward the world and toward the act of taking pictures. And of course these images show an interesting journey through the first movies I made. There was some sort of testimony in these Polaroids that I thought could be interesting to oppose to our present culture of instant picture-taking.”

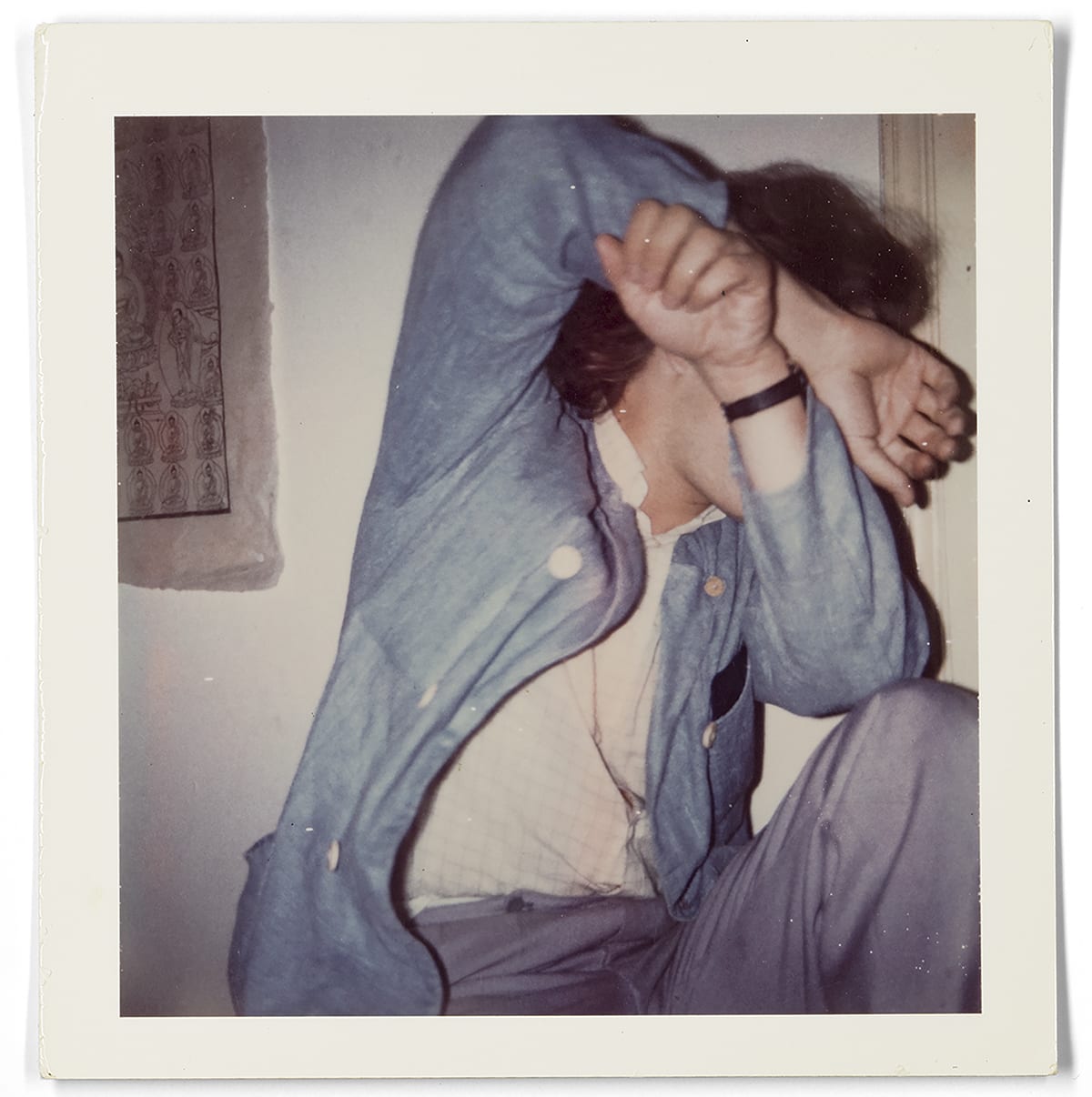

For Wenders, Polaroids were not art. Rather, they were spontaneous, playful and communicative objects that celebrated the uniqueness of the individual moment and the “unmanipulated truth” of time. It’s something that can be seen in the blurry mystery of New York Parade, 1972, the suggestion of chat in Heinz, 1973 and in the intimate portraits of actors such as Dennis Hopper, who starred in Wenders’ 1977 film The American Friend.

“There was always a little bit of awe in connection with taking a Polaroid,” he says. “After all, you held a one-of-a-kind thing in your hand that couldn’t be repeated (I don’t know anyone who ever made other prints from Polaroids). It was a one and only, unique object that was an incomparable proof of whatever just happened before. Even if you took many, each one was like looking at a little marvel, an original! There was always a sort of ‘wow’ to it. That ‘wow’ is largely gone now.”

So how can contemporary photographers strive to reclaim the honesty that he feels was reflected in Polaroids? “It’s amazing how young photographers today try to capture ‘truth’ with their contemporary cameras,” he says. “They try to find a sense of honesty with their digital tools and with that whole process. But it’s a difficult struggle for them, because the Zeitgeist and the entire visual culture are against them. They have to be stubborn and insist that the picture they took is really exactly what they saw. The fundamental ‘belief’ that photography is a truth-based medium is gone.”

The title Instant Stories reflects a narrative identity for Wenders and he suggests that the reckless freedom that came with capturing these Polaroids provided a “direct window” into the person he was back then, when he was getting “sidetracked” by making movies, still longing to be a painter.

“When I look at these Polaroids, I see the whole universe of that young man who tried to convince himself that he could be filmmaker, but in his heart still had a nagging doubt about whether that was the right thing to do. You can follow that search in those Polaroids,” he says.

After making three movies that he now feels were derivative – “One that looked like Cassavetes, one that owed everything to Hitchcock, and one that was like a low-budget David Lean” – it was only on his fourth, Alice In The Cities (1974), that Wenders felt he found his own visual “hand-writing”. This, he says, is partially thanks to the SX-70 that he used to help him capture and understand his surroundings.

“That camera was a great seismograph of that time in my life,” he recalls. “It helped me to find a look that was my own, a way of looking at the world in a way that wasn’t arbitrary or random.”

“Finding the frame, spending time in each place on each image and just taking much fewer pictures. It was no longer a spontaneous carefree act, like in those 15 years of doing Polaroids. In my mind, I didn’t produce ‘photographs’ when I took Polaroids though. I just shot the heck out of everything. It was taking notes; a part of living. It was like thinking, breathing, laughing.”

I point out that this is starting to sound a little bit nostalgic. “The Polaroids in this exhibition are each a unique thing,” he says, “You produced an instant print. You don’t do that with your iPhone now. These little objects were an instant communication between people. You could hand this actual thing over to them. They were proof and memory. It was the last genius outburst of the analogue era.”

He pauses. “Polaroids marked a phase between the first 150 years in photography and the digital age. It was science fiction. It was the past and present all in one and we didn’t even know it or appreciate it, then.”

Nonetheless, as far as he is concerned, the ship has sailed for him to start taking Polaroids again. “Once I started working on my Plaubel and mid-size negative, I got addicted to real photography,” he shrugs. “There was no way back to Polaroids for me…”

But he admits that, just like everyone who will come to see Instant Stories, he takes hundreds of pictures on his smartphone every week. “It’s a bit sad,” he says. “I know I’ll never even look at them. I have to ask, who the hell is going to look at them?”

“For me, that is built into the very word ‘photography’: Taking something from the world, once, and keeping it. In a strange way, that uniqueness was manifested in Polaroid more than in any other photographic act before or afterwards.”

Instant Stories is on show at The Photographers’ Gallery, Soho until 11 February 2018 https://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/wim-wenders-instant-stories