The DJI Drone Photography Award is now open for entries, giving two photographers the chance to realise their dream drone-shot photography project. Submit your proposal now!

Aerial photography boasts a certain honesty. While from the ground, structures can be sheltered from public view, tucked behind pristine hedges or towering fences, when viewed from the sky there are few places to hide. For South Africa-based drone photographer Johnny Miller, this was the very appeal.

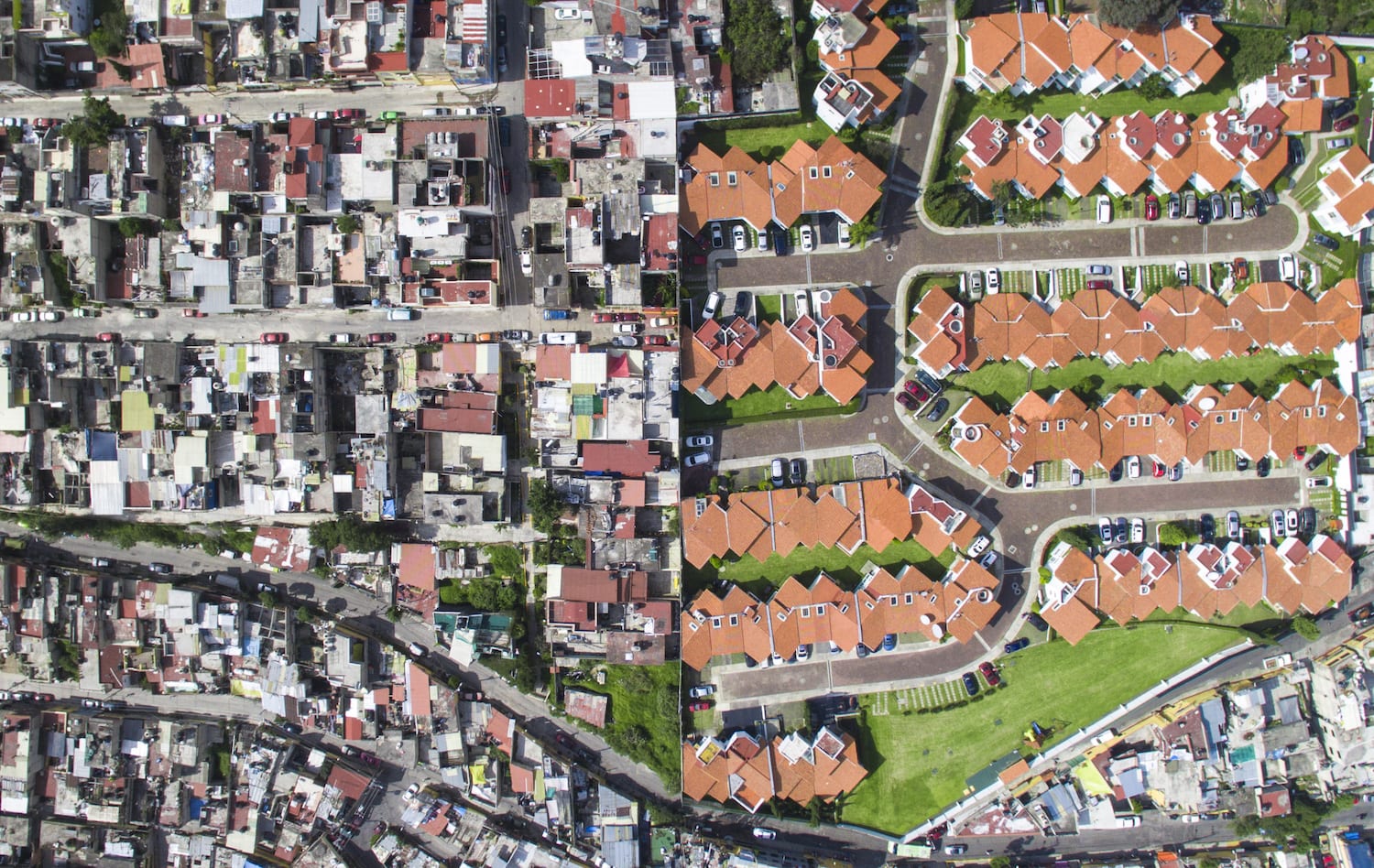

Unequal Scenes is a series of photographs taken first in South Africa, and later across the world, that sheds light on the unequal distribution of wealth and inequality currently present in society. Using a DJI drone, Miller photographs what you cannot see from the ground: extreme poverty living on the doorstep of privilege and wealth. While one photograph shows a luxurious golf course backing onto a densely populated settlement of tin shelters, another juxtaposes the swimming pools and private driveways of an affluent housing complex with a neighbouring township. There are at least four times the amount of dwellings sandwiched into the township than the private complex.

Without a drone, Miller’s project would fail to exist. By providing a new perspective on a pre-existing situation, Unequal Scenes has an undoubtable impact. The DJI Drone Photography Award, in a similar vein, is seeking project ideas that explore narratives and subject matters that would be impossible to capture without the use of a drone. The competition is free to enter and two winners will receive an assortment of prizes including £1,500 project financing, a DJI Phantom 4 Pro drone and an exhibition at a major London gallery.

To provide readers with inspiration for the competition, the British Journal of Photography spoke to a number of photographers each approaching drone photography a little differently. In the interview that follows, Miller discusses his first interaction with drone photography, the process of creating Unequal Scenes, and the importance of drones in opening our eyes to the social issues facing the world.

How did Unequal Scenes come about?

I came to Cape Town from the US in 2012. I was a photographer and interested in getting my masters degree in Africa, so I studied Anthropology at the University of Cape Town. During my course we covered a lot of topics. Some of the most interesting concerned the spatial planning and architecture of the city, specifically the particular way that it was approached under apartheid. For example, there are huge buffer zones that were created to keep different racial groups separate. I thought that was fascinating. When I bought a drone in February 2016, I had a spark of inspiration that perhaps I could capture those separations from a new perspective.

Why were you interested in documenting inequality in South Africa and further afar?

When I moved to South Africa, the inequality was impossible to ignore. From the minute you land in Cape Town, you are surrounded by shacks. Tin shacks surround the airport, which you have to drive past for about 10 minutes until you reach the more affluent suburbs where privileged people, myself included, live. Most people intentionally never to return to these areas. That’s a status quo that I’m not okay with. To paraphrase Barack Obama, inequality is the defining challenge of this generation. It is not confined to one region of the world. It is not confined to one group of people, or one nation – it is intersectional and it is international. What I’m trying to do with Unequal Scenes is provide a visual language to discuss inequality. To help bring the topic into the public consciousness.

Why is drone photography a powerful tool in articulating the severity of inequality present in the world?

Drone photography is interesting because it upends people’s previous perceptions of the world. I clearly remember the moment when I got the idea for Unequal Scenes – I had shot a video of Table Mountain and showed it to my friend. He said: “Wow! I’ve never seen Table Mountain look like that!” I thought about it for a moment and then realised that he had experienced a total perspective shift from what he thought he knew, and what he had seen his whole life in one particular way, to something different. I realised that this power to change perspective was inherent in drone imagery, and moreover, it was now affordable for people like me to experiment with.

For what reason did you start working with a drone?

I started working with my first drone, a DJI Inspire, in February 2016. I bought it to add value to my photography business. At the time, drones were brand new in South Africa and I wanted to capitalise on that appeal.

Drone photography has the stereotype of being purely pretty landscapes. What does it offer photojournalism and social-facing photography?

The power to shift someone’s perspective allows you to do two critical things. Firstly it displays a social justice issue in a new way so that people may also get talking, or thinking, about that issue in a new way. Secondly, drones are sexy and in today’s media-heavy environment, you need to have something that stands out from the crowd. You need “wow” images that stand out on someone’s newsfeed. The aerial perspective, although more and more people are doing it, certainly does that.

How did you identify where to take the photographs?

I use a variety of research tools. This is a combination of census data, maps, news reports, as well as talking to people. In South Africa and the US, for example, I used mapping tools created with census data. In Mexico City I relied on prior inequality photography by the helicopter pilot Carlos Ruiz. So there are a variety of ways I do my research.

Once I identify the areas I want to photograph, I visualise them on Google Earth, and try to map out a flight plan. This includes taking into account air law, air safety, personal safety, battery life, range, weather, angle, time of day, and many more factors. This is not to mention all the logistics that go into taking aerial photographs around the world: hotels, rental cars, grasping different languages. It’s sometimes hard to juggle all these factors by myself, although I have had some amazing friends in various cities who have come with me to some locations for support, which I’m forever grateful for.

You aim to portray scenes of inequality “as objectively as possible.” How does a drone facilitate this objectivity?

The drone provides a separation from the subject that can be powerful, especially when dealing with an emotionally charged issue such as inequality. The height and distance provided by a drone allows the viewer to see inequality almost as if it were a structural problem: the drone photos become patterns, colours, and shapes, rather than individual people. This, I think, allows the viewer to engage a different part of their brain – perhaps a less judgmental part of their brain. It’s almost as if you are looking at a map, or an atlas. That is what I call objectivity. Of course, that’s false – my photographs are completely subjective as I choose the frame and the location in which I shoot. That said, it may still be more objective than photography on the ground.

Elevate your photography with a new perspective! The DJI Drone Photography Award gives two photographers the opportunity to realise their drone-shot projects. Submit your proposal here!

The DJI Drone Photography Award is a DJI competition supported by British Journal of Photography. DJI is the world’s leading manufacturer in high-end drones. Please click here for more information on sponsored content funding at British Journal of Photography.