Congenital achromatopsia is a hereditary condition in which the eye cannot detect colour – the cones in the retina do not function, leaving the vision to the rods alone, which only detect shades of grey. In most places the disease is rare, occuring in less than one in 30,000 people. But on the Micronesian island of Pingelap it’s much more common, present in more than 5% of the population.

The islanders have many theories as to why. According to one, the disease came from Dokas wife of the 19th century ruler Nahnmwarki Okonomwaun, who had two achromatopic children said to have been fathered by the god Isoahpahu. Another myth references an angry missionary, who cursed Nahnmwarki Mwahuele; yet another warns pregnant women off walking on the beach at noon, lest the blazing sun partially blind their unborn children.

Whatever the cause it’s an extraordinary phenomenon – and one that immediately gripped Belgian photographer Sanne De Wilde when she heard about it back in 2015. “I was invited onto a radio show to talk about my project Samoa Kekea, about albinism on the Polynesian islands of Upolu and Savai’i,” she says. “Afterwards I was contacted by Roel van Gils, a Belgian man who has achromatopsia, who said ‘I have a story for you’. I met him and was immediately very interested. I felt I had to do it.”

“Sometimes an idea sparks your mind and lingers, glowing in the dark in the back of your head, like a shiny thought-sparkle,” she writes in the afterword of her new book, The Island of the Colorblind. “That is how Pingelap came to me. I was told the island-tale and instantly felt I had to pluck this shooting star out of the sky, hold on to it, care for it and let it guide me.”

“The Dwarf Empire was very much about voyeurism – the person who set up this place turned it into a theme park featuring the little people, but by photographing them I was taking part in that,” she says. “I wanted to turn that around and encourage people to think about it.

“I’m very interested in how our physical identity is created,” she adds, “what it means to be born into a particular body or to transform yourself into something else.”

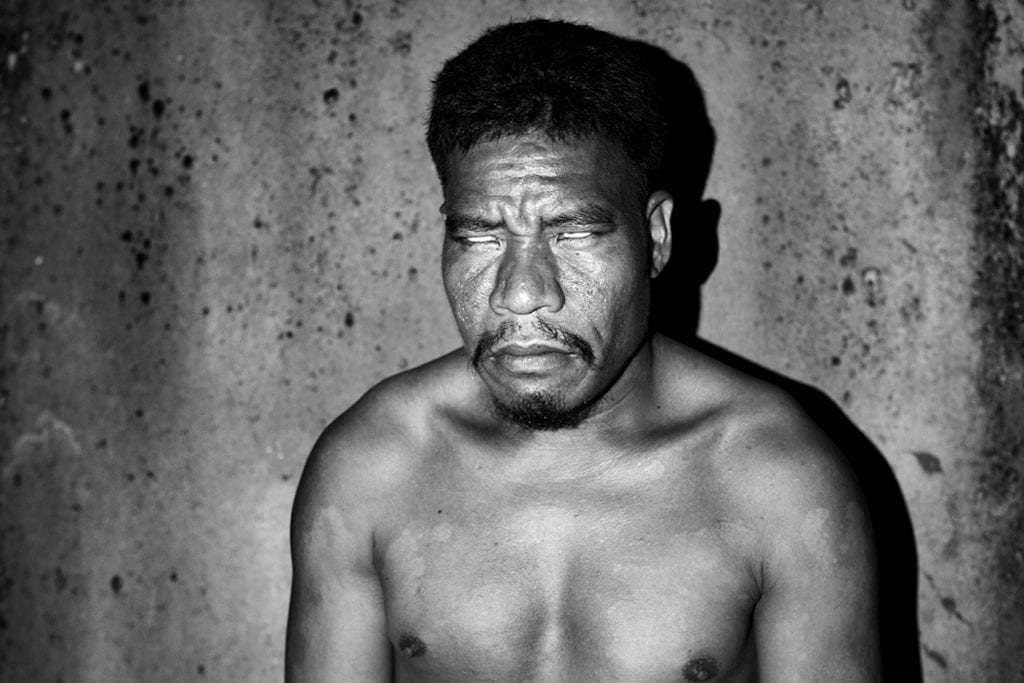

The Island of the Colorblind is different again – yet plays with similar themes. Featuring people with an unusual genetic condition, it uses images shot on infra-red, in black-and-white, printed on coloured paper, and hand-painted by people with achromatopsia, to encourage readers to question their own perception of colour.

“I like to shoot each project differently,” says De Wilde. “I never try to do the same thing – I use different ways to show different things. I show the same image in different colours so you have different perspectives on it.

“I had been looking for a project which would allow me to explore different ways of using the medium, but I didn’t want to just do it for the sake of experiment,” she continues. “In making this project, I could really work with this idea of colour, the loss of colour, and perception. It felt like something I had to do.”

Shooting it wasn’t easy though, with De Wilde funding a trip to Pingelap by herself, and fitting it in around her freelance work for Dutch daily De Volkskrant. She eventually managed to go for a month in November 2015, via a long journey that even the travel agent tried to talk her out of; she tried to prepare as much as possible, but her infrared camera arrived late, and the first time she used it was on the island.

“It was timing, but also a conceptual choice,” she says. “I intended to work this way – to let go of control over the use of colour and allow myself to be surprised; to let the medium take over, not knowing what the result would be.

“It was digital so I could see what I was doing, but I had no time, so I was working all day, from morning to night, to make the most of it,” she adds. “And the last time I shot black-and-white I was 16, and developing my own work in the darkroom.”

“I easily forget this was the toughest trip I ever made,” she writes in her book. “Once on the islands, every step I took felt like fighting gravity. I struggled, battling what felt like a different physical dimension, my body weighed on me, as if something was constantly pushing me down. I had to face corruption, ignorance, and the overwhelming feeling of being utterly useless and unable to achieve or help, in this new reality.

“I gathered my strength, from morning to night, to meet every achromatope on the island.”

De Wilde’s project includes portraits and photographs of the people she met, both those affected by achromatopsia and those not, as well as lush landscapes portrayed in unexpected, though beautiful, colours. “When I was taking the pictures I had a clear idea of what I was aiming for,” she says. “Vision is very important, so when I was shooting I was looking at the visible. I was trying to look at the island through someone else’s eyes.”

Back in Amsterdam, where De Wilde has settled after growing up in Antwerp, she got in touch with an organisation for achromatopic people and organised two workshops, asking them to hand-paint her black-and-white images. Some of those present asked her to label the paint pots so they could choose the ‘right’ colours, but she respectfully resisted their wishes. “For me it wasn’t about good or bad, I was just interested in different ways of seeing,” she says.

“I wanted to find ways to integrate unexpected ways of looking at things. The painting was very important because it is often the point where, as a child, people are told they’re doing something wrong – they’re painting the sun purple not yellow. I wanted to embrace that diversity, and the idea that our reality could be more colourful.”

“When my parents and kindergarten teacher discovered it was impossible to teach me different colors, someone came up with the idea of labelling colored pencils,” writes Roel van Gils in De Wilde’s book. “Once I was old enough to read, I was all of a sudden able to color the sun yellow instead of blue, green or purple. At first, I was very proud. But in retrospect it didn’t really matter. What’s wrong with a purple sun?”

After Arles the exhibition moved to the Phi Center in Montreal, where De Wilde changed the installation again. “I don’t like repetition,” she says. “It’s important for me to show it differently each time, to keep it an ongoing visual experiment.”

Sanne de Wilde’s The Island of the Colorblind is available at the Kehrer stand at Paris Photo. The Island of the Colorblind is co-published by Hannibal and Kehrer Verlag, priced €49.90. www.sannedewilde.com www.uitgeverijkannibaal.be www.kehrerverlag.com