All images © Miranda Barnes

In Social Season, Miranda Barnes’ debut photo book published by MACK’s imprint Important Flowers, cotillions are spaces where teens tenderly display pride and aspiration

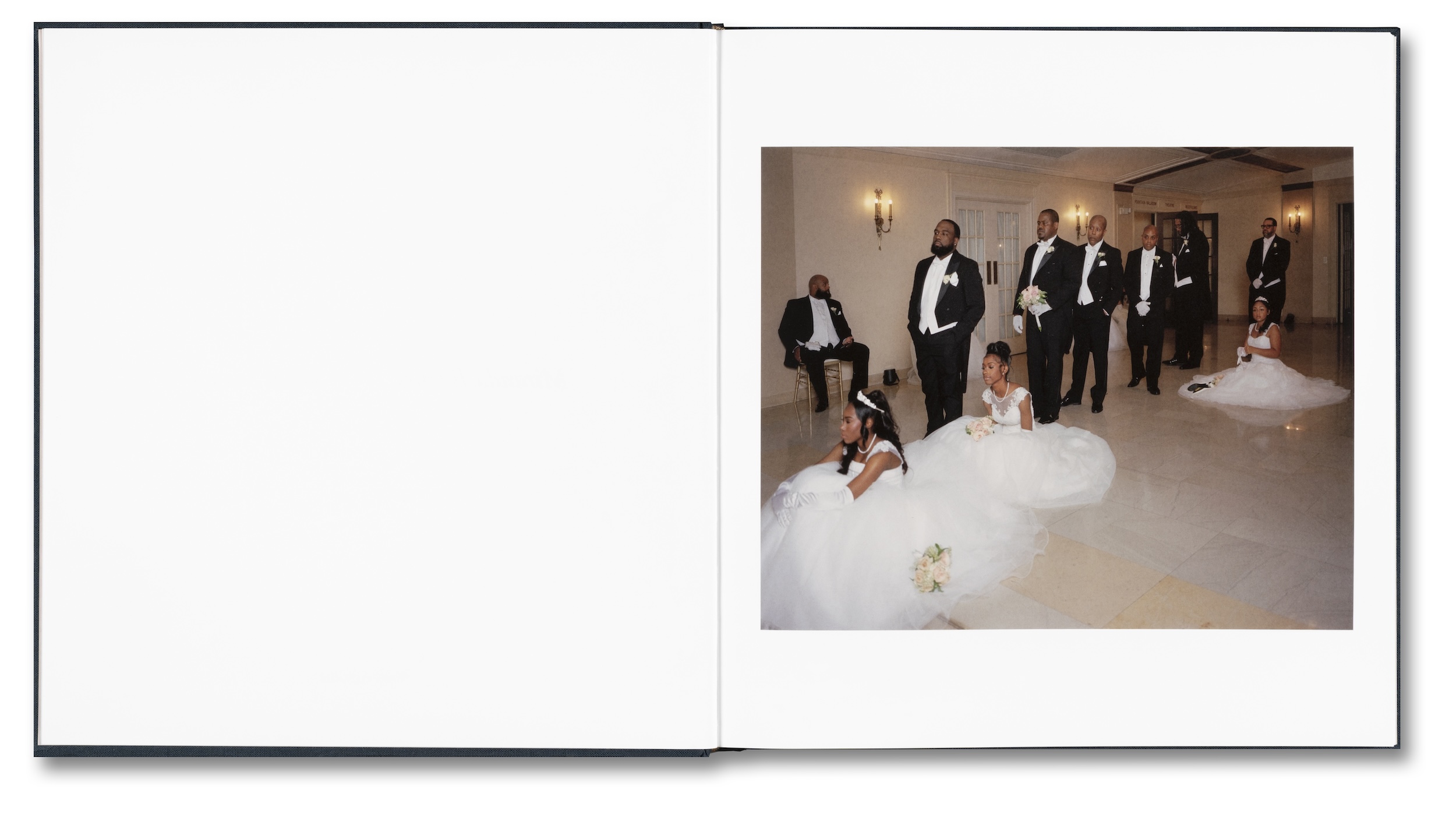

In Miranda Barnes’ debut book, Social Season, Black American boys and girls are adorned in white gowns, pearls, tiaras, and tuxedos. They dance and laugh with quiet anticipation, walking hand in hand with relatives, smoothing tulle, and sneaking snacks as they wait patiently for the evening’s ceremonies to commence.

Rooted in a nineteenth-century tradition, Black American debutante balls and cotillions have long been overlooked in art and cultural discourse. With Social Season, Barnes begins to address this absence.

The project, which began in 2022, developed after she spontaneously reached out to Dr Renita Barge Clark, co-founder of the Cotillion Society of Detroit Educational Foundation. Each April since, the Caribbean-American photographer has spent a day inside Detroit’s Masonic Temple, documenting the Society’s annual debutante ball for accomplished young members of the Black community.

“I sought to challenge the heavier-handed assumptions people often make about Black youth, so centring joy became essential”

Recently published by Sofia Coppola’s imprint at MACK, Important Flowers, the book follows these balls over four years. Through a series of undated photographs, Barnes depicts a community’s annual celebration of youth on the cusp of adulthood. Admission is highly selective, requiring strong academics, sustained volunteer work, and proven leadership. Yet, as Barnes notes, this rigour has long defined Black cotillions. “They’ve always been about education,” she says, serving not only as a child’s introduction to polite society but also a parent’s enduring hope for their future success.

Despite the ball’s formal atmosphere, Barnes’ photographs convey a pronounced sense of humanity. They foreground youthful innocence and a quiet, self-possessed grace – attributes frequently marginalised or systematically excluded in prevailing visual representations of Black life. Articulating this sensibility with careful attention, she blends formal portraiture with candid observation, creating a balance that, despite her own claims, elevates the work beyond mere documentation into something profoundly more intimate.

In one image, a young debutante waits to be presented, while an older man – likely her father – leans against a handrail, momentarily dozing off. “I remember snapping that photo,” Barnes recalls. “He woke up, and one of the other dads laughed, saying, ‘Be careful, she caught you slacking.’” Long wait times have become an integral part of the ball’s rhythm, especially as the number of debutantes grows. Tired fathers linger behind to escort their daughters, while the girls gather to touch up their make-up. “But those are the moments when the most beautiful expressions emerge,” Barnes says. “You see love and humanity in how people respond when things quiet down.”

This sensitivity reflects Barnes’ increasingly deliberate approach. “Sometimes it’s not even about what I’m photographing…it’s a feat,” she says. “Can I fill the frame or catch an action shot when no one’s looking? Those perfectly timed, candid moments are what I dream about.” Yet in the cotillion setting, precision often collides with unpredictability. “You’re telling twenty kids to pay attention,” she adds, “and they’re all looking at you like you’re crazy.” What unfolds instead is the gentle chaos of youth – silliness, mischief, humour – asserting itself within a formal environment. It is precisely this interplay of care and chaos that she finds most compelling – parents chasing children, children chasing friends, and Barnes moving quietly among them, camera in hand.

Through her photographs, the debutante ball essentially emerges as a ritual of discipline and hope, where the excellence of Black youth is sustained through collective effort and intergenerational devotion. Rejecting reductive political frameworks, the images trace a logic of sacrifice that resonates across diasporic communities, whose futures have been shaped through the love and care of their predecessors. “That’s what is so moving to me,” Barnes says. “Being a parent and wanting everything for your child… no matter the circumstance. That’s not just a Black thing; it’s a human thing,” and it is precisely this ethic of sacrifice that Barnes’ work renders powerfully legible.

“Dr Clark’s essay at the end of the book really brings this together,” she explains. Reflecting on the origins of the Cotillion Society, which she co-founded with her late husband in 2009, Dr Clark writes that it began with a simple desire to create a brighter future for their daughter, Lexi. From that initial gesture of love, she and her husband have helped propel an entire community forward, as hundreds of debutantes have since celebrated their entrance into polite society, even amid a turbulent present.

“If there’s one thing to take away from my images,” Barnes says, “I want it to be this intergenerational celebration. Throughout the project, I sought to challenge the heavier-handed assumptions people often make about Black youth, so centring joy became essential. My photographs matter, of course, but Dr Clark drives home the core point. Sustaining this tradition in Detroit… bringing hope and happiness to young people is a remarkable achievement, and I feel honoured to bear witness to it.”

By rendering this sacrifice visible, Social Season reconceptualises the debutante ball as a living site of resilience and self-determination. Through her intimate imagery, Barnes positions these rituals as spaces where Black and diasporic communities actively reimagine and enact possibilities for joy and fulfilment in contemporary America – not in spite of structural or historical challenges, but as a deliberate form of resistance to them. Her work beautifully demonstrates that where communal bonds are sustained, hope for the future is reinforced, and these debutantes stand as emblematic agents of that intergenerational continuity.