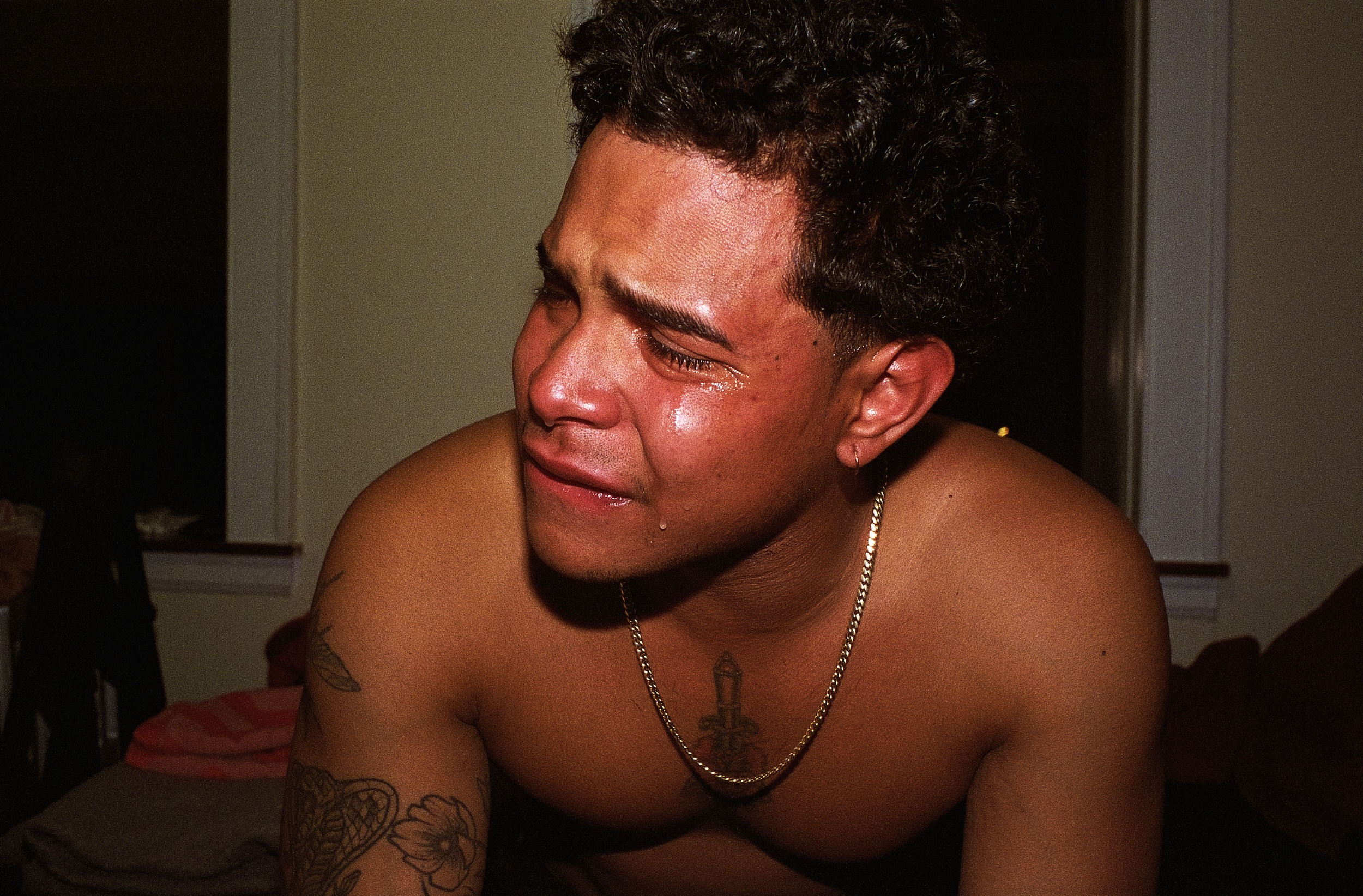

Ivan crying in my bedroom, 2021. All photos © Dean Majd

A decade-long photographic record of grief, masculinity, and community in Queens, Hard Feelings traces how intimacy endures amid loss

One of the earliest images in Hard Feelings, Dean Majd’s 10-year photo series, is a picture of a friend standing at the mouth of the Hell Gate Bridge. It’s nighttime in Astoria and the sky is a dusky yellow smudge, city lights brooding in the distance. Framed by imposing steel arches, the figure turns towards the camera, his bloodshot-eyes locked on the lens, before – we imagine – disappearing with the railroad tracks into the darkness.

Crossing the Hell Gate Bridge by foot – which carries high-speed Amtrak and freight trains across the strait of the East River that separates Wards Island from Queens – is both highly dangerous and highly illegal. “It’s a rite of passage for young men who grew up in Astoria,” says Majd. “You walk through the gates of hell to prove you’re a man.”

If the bridge is a threshold into manhood, the picture is a portal into Majd’s epic yet intimate debut solo show, which follows his inner circle in Queens in the years before and after the Covid-19 pandemic. Curated by artist Marley Trigg Stewart and on view at Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York, Hard Feelings is a portrait of self and community, and a “New York odyssey” – taking viewers through urban and psychic underworlds, to the peaks of love and the depths of loss, through the twists and turns of healing.

Majd’s diaristic impulse can be traced back to childhood, when, as an introverted seven-year-old, he received his first camera from his mum and discovered a new way to relate to the world and to himself. But Hard Feelings truly began in spring 2016, when Majd, then 25, reconnected with and photographed his childhood friend James at their local skatepark. A week later, James died in a subway accident. In the wake of the tragedy, Majd grew close to James’s best friends – a group of young male artists within Queens’s graffiti and skateboarding scene. They held firm to one another through their grief, and for the first time, Majd felt like he’d found his people.

“After James passed, my camera and my life, my friends’ lives – all those boundaries dissolved,” he explains. “My camera allowed moments of vulnerability between these men, mostly men of colour, who felt they had to be invincible in order to exist in the world.” By the end of the year, he told his friends he wanted to photograph every aspect of their shared lives: “The good, the bad, the anger, the fear, the tears, the happiness – all of it. Up and down, left and right.” Through their trust and encouragement, Hard Feelings was born.

“I wanted to craft a legacy for them, map out a hero’s journey of our own”

Image-making is a near-spiritual act for Majd, who was born and raised in Astoria, a multi-ethnic neighbourhood of Queens – the so-called “world’s borough”. Shaped by a constellation of cultures and communities – “Arab and Muslim, Italian, Brazilian, South Asian, Irish, and many others” – his early visual world was richly layered. It was through Astoria’s large Greek community that he first encountered Greek mythology: heroes and gods and attributes writ large.

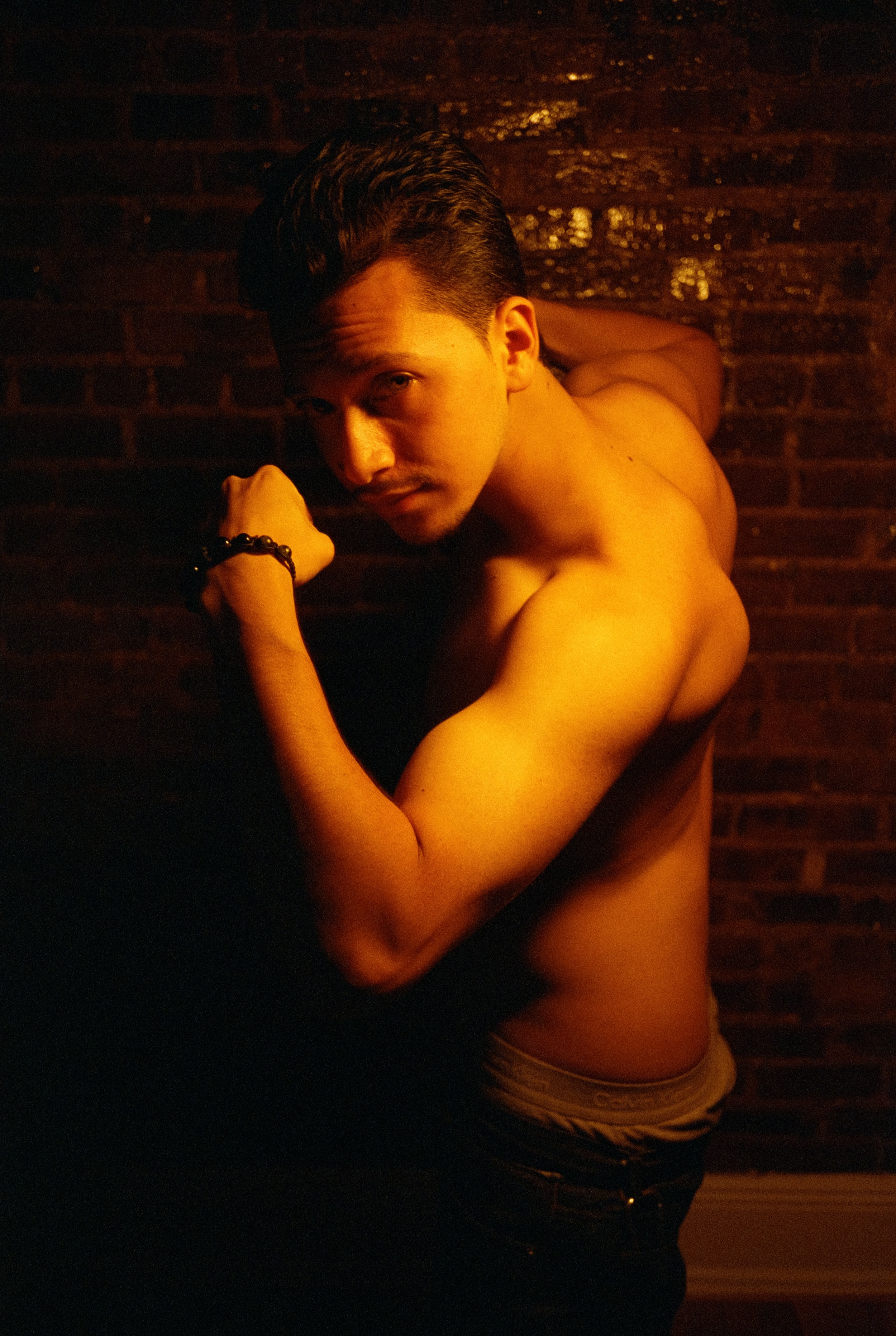

Those classical narratives became even more vivid for Majd during an acid trip early on in the series. “I remember looking around at my friends and visualising them as these mythological beings, and really realising this human need to mythologise our own stories,” he explains. “I came to understand that I’d become a record keeper of our truths. It’s not just that these young men were told to be invulnerable – it’s that they were told, visually or directly, through politics or socio-economic reasons, that their lives simply didn’t matter. I wanted to craft a legacy for them, map out a hero’s journey of our own.”

There’s a Promethean charge to Hard Feelings. Whether through spirituality, substances, or graffiti culture, it becomes a dance with death: an act of “chasing the ghost”, as Majd puts it. He recounts “nocturnal quests” through Queens: “the addictive thrill” of intoxication, of staying out all night scaling buildings and writing your name on walls, in the knowledge it might be erased the next day. “The closer we were to death, the more alive we felt, the more we played with fire,” he says. “It was in these nighttime spaces that we could be our most open.”

Over the decade, their Queens community lost seven others, including Majd’s dear friend Suba, who died of an accidental overdose in 2020. Majd’s images contain the crucibles of grief: break downs, broken hearts, skin broken in self-harm. Wounds are everywhere, but so is the intensity of life that the cracks let in. “Grief was all around us during that time,” he says. “I think it pushed us further into our vices but it also pushed us further into each other, like alchemy. Our bonds were formed by pain, but they were bonds of love that felt very infinite.”

That emotional intensity is conveyed through Majd’s lush visual language. Made mostly at night or indoors with point-and-shoot cameras, his film photos speak through deep shadows and bursts of illumination. His compositions are impromptu yet cinematic – the world beyond the frame palpably felt. “What I didn’t realise is that in making images in a very candid, aesthetically direct way, I was creating photographs that felt very surreal. I think it’s in the surrealness of the image that the truth cuts even deeper,” he reflects.

As Trigg Stewart, Majd’s curator and long-time friend, notes: “Hard Feelings brings up this interesting contradiction that’s inherent to photography, when it comes to the treatment of memory. Dean’s aesthetics are very beautiful, but they don’t romanticise the often traumatic experiences that are being depicted. Instead, they validate what those experiences amounted to, and I think that’s really powerful.”

Two of the most aching images in the show are portraits of Suba. ‘sunshower’ (2020), the only image taken in daylight, sees him topless and grinning in a summer storm, electric and alive. (Majd can’t look at the image now without hearing a line from Suba’s favourite Fleetwood Mac song: “When the rain washes you clean, you’ll know.”) The next is an interior shot taken months later: ‘suba’s bedroom after clean-up (the place of his overdose)’ (2021). Between the two lies Majd’s deftness at capturing the extremes of existence: its euphoric heights and unbearable heft.

“The process of record keeping weighed very heavily on me, but it was always a self-imposed burden,” he explains, before taking a beat. “It’s actually healthy for humans to forget – it’s an act of relief. Through photography, I don’t let myself, and that’s the alchemic exchange. Everything beautiful in my life has come with a lot of pain, and everything painful has brought a lot of beauty.”

Palestine does not reveal itself explicitly in Hard Feelings, but the series is indivisible from Majd’s Palestinian-American identity. “Being Palestinian means I understood grief at a very young age – the violence my family and I, and our relatives back home, have been subjected to. I also learned that grief and empathy go hand in hand,” he says.

Masculinity runs alongside violence as a tension in the show. Even in the most confronting of times. ‘self-mutilation (getting high)’ (2018), an image of a scarred arm, and ‘rissa (battered)’ (2018), his tender portrait of a female friend with a black eye, bear witness to the destruction of self and others, and the myriad ways societal violence plays out.

“Hard Feelings is this complicated record of truth that speaks to the complexities of the male experience, in a country that’s dealing with a reckoning with masculinity and patriarchy and how it has caused so many ails in the world – from the extreme violence of ICE, occupation, genocide, and imperialism, to interpersonal family and relationship structures, and how we connect to ourselves and the people around us.”

Trigg Stewart agrees. “We’re only weeks out from the murders of Alex Pretti and Renee Good by federal agents in Minneapolis. It’s an incredibly charged moment to be organising a show celebrating masculine vulnerability, when masculinity (in the service of white supremacy) is being weaponised to terrorise people in real time across the globe,” he says. “This is certainly not new, but it is a good reminder of how art provides respite and catharsis in these fucking agonising times, while reinforcing what community actually means – tangible advocacy and care.”

If viewers enter Hard Feelings via the Hell Gate Bridge, they exist via ‘Heaven’s Gate’ (2019): a photograph taken through a window, in which celestial beams of light seem to stream through an abandoned building. “Towards the end of the show, I wanted to chart a path to hope,” Majd adds. “I hope strangers can see themselves in the work. I hope that it can lead to healing, for those who need it.”

Hard Feelings opens on 04 February at Baxter Street at Camera Club of New York. Hard Feelings will be published as a book by Aperture in 2027

@deanmajd @marleytriggstewart