Algerian Man from the Ellis Island Portraits Series, 1910 © Augustus F. Sherman (1865-1925)

Curator Hiba Abid stresses the importance of rectifying inaccurately archived photographic materials about MENA communities to resist erasure or over simplification

In 1910, a young man left his family somewhere in the Algerian Sahara, boarded a boat from North Africa’s coast, and headed for the glimmering city of New York that he’d only heard rumours and fantasies about – the American Dream, they called it. Arriving at Ellis Island, he felt as all immigrants have felt throughout time; a little frightened, quite alone, and full of wonder and excitement at the potential of a life that lay ahead of him. He has his portrait taken hurriedly in a makeshift studio, hundreds of new arrivals standing in line behind him, he has his papers stamped, and he is waved through, passing the threshold of a ‘New Yorker’.

This is what I imagine happened, at least, as I stare back at the sepia-toned photograph – labelled only ‘Algerian Man’ – of this young man in his Sahrawi robes and headcloth on the walls of the New York Public Library. Today, his image is part of the exhibition Niyū Yūrk: Middle Eastern and North African Lives in the City in the library curated by Hiba Abid, curator for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies. She is the first and only curator of her kind at the iconic institution.

“I keep on looking at [the Algerian man] and he really feels present,” Abid tells me. “I keep on thinking about his way back to French Algeria, what happened to him after that? What was his life like? This exhibition makes people look at these portraits and humanise [these immigrants]”.

The show has opened at a charged moment in time – with the ongoing Israeli assault on Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank, President Trump’s order of ICE raids across the country, and the New York Mayoral elections around the corner (Zohran Mamdani would go on to become the city’s first Muslim mayor, and Abid now sits on the Mamdani’s cultural advisory board), the show perhaps couldn’t have been more pertinent than it is now.

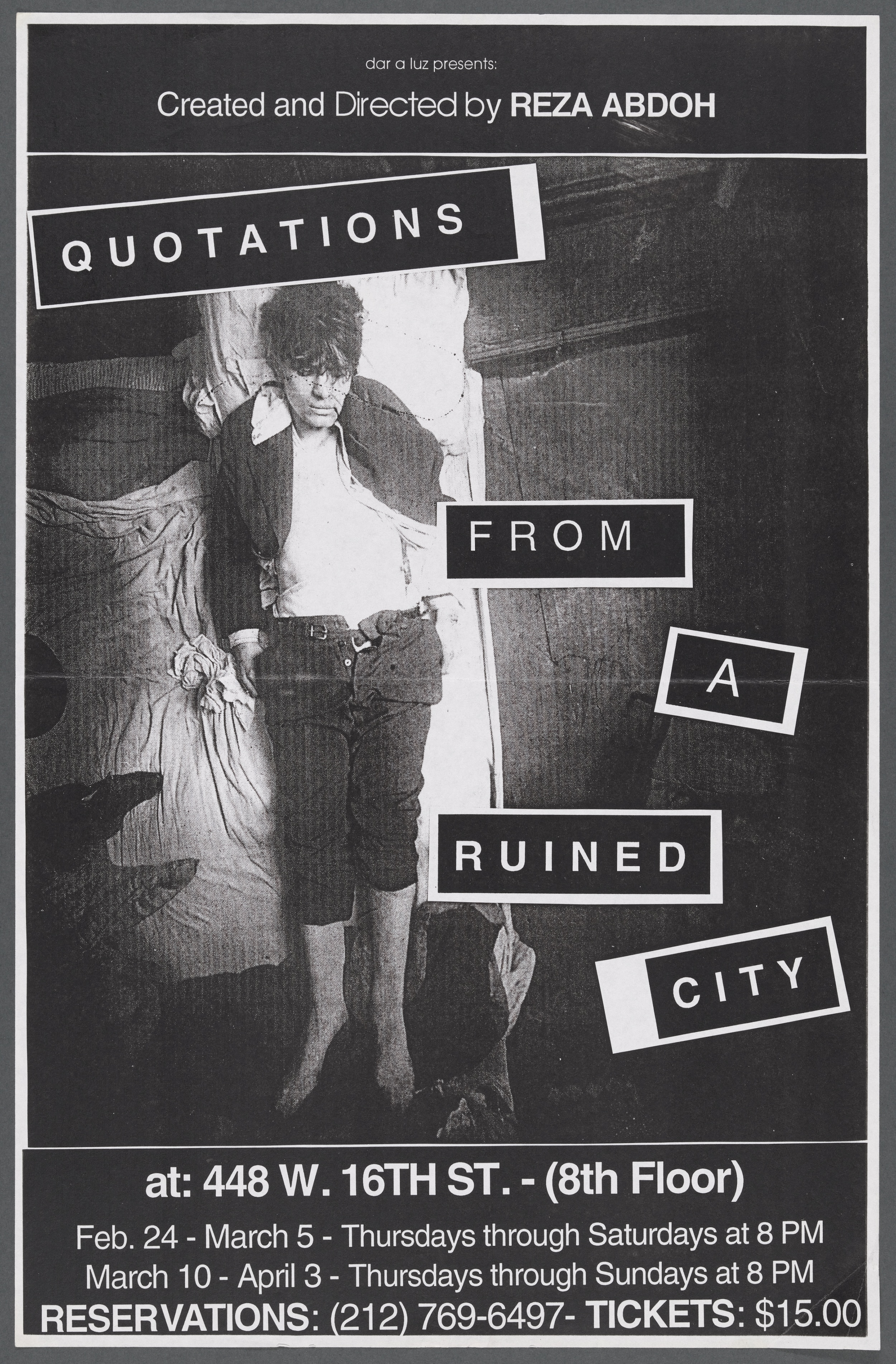

Niyū Yūrk is structured somewhat chronologically but also tries to group work into loose themes, using only material from the library’s Middle Eastern collections. Using photography as well as film, sound and print media, Abid says she “wanted it to be a proud celebration of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) cultures, of their contributions in different fields, from businesses that serve daily lives of New Yorkers, to the earliest music recordings in New York City.” She references artists such as Iranian-American theatre director Reza Abdoh, “and these are things that you probably don’t expect when you go see an exhibition like this. You probably expect it to be these timelines of immigration to New York. But I wanted to show the breadth of all these contributions and in areas where you probably didn’t expect MENA people to be at the forefront of theatre or electro-acoustic music.”

This celebratory tone is carried throughout the show to the photographic series by Mahka Eslami, Bodega Boys, highlighting moments of daily life and joy in Yemeni corner stores around New York City. Elsewhere in the exhibition, there are clips from In My Own Skin, which documents the aftermath of 9/11 as experienced by five young Arab women living in New York.

When Abid began her role in 2022, she was asked to identify the library’s earliest Arabic diasporic materials from New York City, items that have been collected since the founding of the Oriental Division in 1897. The institution’s initial request for the exhibition – to focus on early 20th-century immigration – felt too narrow for Abid. “I considered that wouldn’t be inclusive of the more diverse waves that came later after Christian Syrian immigration,” she explains. “I really wanted to tell that story, especially at this moment now when there is a need to be seen, to be represented in these institutions.” Her insistence expanded the exhibition all the way to the present day.

The process also raised questions about institutional responsibility. The library, Abid says, has taken seriously the matter of who shapes these histories. “We’re a public library and the library had to fight and advocate to have a Middle Eastern curator,” she says. “It was a priority… to have someone from a Middle Eastern background to tell these stories.” That work includes addressing inaccuracies inherited from earlier cataloguing. Images by immigrant-era photographers like Lewis Hine and Augustus Sherman often arrived with limited information. “These photographs… were collected as they were described by these photographers,” Abid explains. “But today we’re in 2025. We have curators with subject expertise. We also hear from the public.”

One example is a portrait long labelled “Armenian Jew,” corrected only after the man’s descendants contacted a museum exhibiting the photograph. “They said this is our great-grandfather and he’s a Yemeni Jewish rabbi from Jerusalem,” Abid says, and the record was later updated. “That’s very important,” she adds, “because all these identities are conflated under one label. It’s our responsibility to complicate these histories… and that’s also what the exhibition is about.”

Some histories required different approaches altogether. Abid searched for materials documenting the Muslim experience in New York after 9/11, a defining period for many MENA communities, and found few. “Our collections had gaps in that regard,” she says. But she discovered In My Own Skin. “It allowed me to tell that story,” she says. “The experience of those who were identified as Muslims in that moment of New York history that extends to the present day.”

Working with early ethnographic portraits also brings mixed feelings for her. “Yes, they are very ethnographic and they sometimes bother me,” she admits. But she finds value in using them to address cataloguing practices and inherited narratives. “What do we do with these materials? I love the challenge to almost subvert them and use them in a different way… than the stories we’ve heard already.”

Visitors have been responding strongly. “I was surprised to see friends or visitors getting very emotional,” Abid says. “They said we never felt seen or represented and here we’re on the walls of a New York institution.” For many, the library’s grand architecture can feel imposing; the exhibition seems to loosen that. “I’ve never seen this much diversity in the building,” Abid notes. “People who might feel intimidated by that majestic building… now see themselves here.”

And in that shift, the exhibition speaks not only to MENA communities but to many others whose histories in the city have been under-recognised. These are stories of contribution, erasure, cultural work carried out quietly, brilliance that has gone uncredited. “Absolutely,” Abid says when I suggest the show connects to a broader immigrant experience – the hidden labour, the silenced identities, the people whose influence shapes New York while their stories remain unnamed. Here, those stories are given space. The Algerian man on the wall is no longer a footnote.

Niyū Yūrk: Middle Eastern and North African Lives in the City is on until 08 March, 2026 in the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building at the New York Public Library