All images © The Fold, Hoda Afshar

Working with an archive of photographs made over a century ago, the artist folds the gaze back onto the Eurocentric lens that shaped the images in The Fold

In 1918 Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault, a French psychiatrist and photographer, travelled to Morocco for a second time (his first was in 1915, when recovering from a war wound). While there, he took thousands of photographs of veiled Moroccan women. These images attempted to fulfil a certain fantasy, one that can be attributed to a French colonial imagination, and were used by de Clérambault to support psychoanalytic theories around covering and desire. Though de Clérambault was making work over 100 years ago, this French fascination with veiled Muslim women remains. Since 2010, France has banned the niqab and burqa in public places, and in June 2023, the Constitutional Council upheld the right of the French Football Federation and similar bodies to ban hijabs (or any other overt religious symbols) during matches.

Iranian-born, Melbourne-based Hoda Afshar came across de Clérambault’s images during her research at the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, in Paris. He was different to photographers she had previously come across in other archives, she says, in the sense that he was fascinated by the coverings, or ‘hayek’, rather than the naked bodies of North African women. He became seemingly obsessed with the hayek, in fact, making almost 30,000 images over two years in Morocco.

After returning to France, de Clérambault continued to photograph the hayek, using models or mannequins to display the coverings. When he realised he was losing his eyesight in 1934, he took a gun and killed himself in front of a mirror and, Afshar explains, his body was surrounded by mannequins dressed in hayek, piles of fabric, and boxes full of handprinted images of women in the coverings.

“I want you to be confronted with your own desire and the frustration that comes from not finding what you’re looking for”

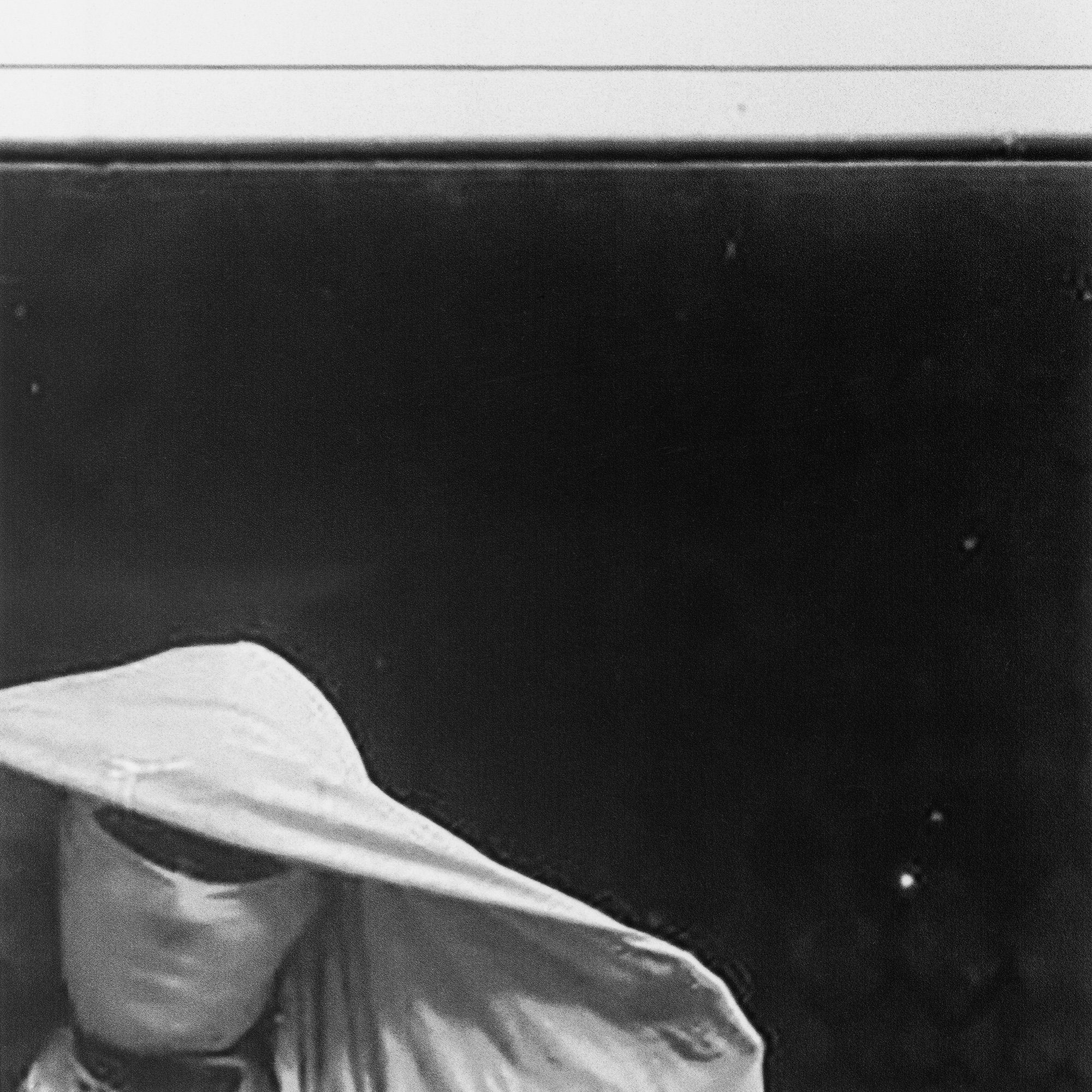

Afshar embarked on a research project on de Clérambault’s archive at Musée du quai Branly, asking to access the works through the digital repository. Saving the images she wished to use, she later returned to them, only to find that the museum software had protected the files, creating crops capturing only a fraction of the image, around the cursor where she had clicked. This created an unexpected effect; a mosaic of hundreds of image fragments.

These ‘screengrabs’ make up The Fold, now on show at the Musée du quai Branly as part of Afshar’s first monographic exhibition in France. Performing the Invisible comprises two bodies of work – Speak the Wind, which was published as a book by Mack in 2021, and The Fold, published by Loose Joints in September 2025.

Afshar’s project potently reveals that the archive is never a neutral collection of documents, but rather a constructed apparatus shaped by power, desire and the political conditions in which it was made. De Clérambault’s Morocco photographs may at first appear to be anthropological or ethnographic studies. Yet Afshar shows that what they really expose is the photographer himself – his compulsions, his gaze, his inability to see the women as anything more than surfaces for projection. The Fold, says Afshar, is not about the nature or environment of Islamic women, but rather the one who sees and tries to represent them.

“I found it fascinating to look at the archive because when you look at these images, they show you nothing about the subject,” Afshar explains. “The image-maker is so removed from the context that these bodies are situated in… You don’t get anything from the images but what you get is an idea of the image-maker.”

At first, the cropped details of fabric folds and shreds of gesture that Afshar accidentally obtained were frustrating. But eventually she came to see the accident as a gift. “It’s like zooming into de Clérambault’s obsession with the fold of the fabric, but also the inaccessibility of the archive,” she says. By enlarging these fragments in the darkroom, she was able to return the material to the analogue processes de Clérambault once used. The result is both tactile and forensic, a deliberate dissection of his gaze.

Afshar stresses that the work is not about reproducing the French photographs, but about dismantling them. “This is a project that works against the images that it’s referencing,” she says. “You would see the cover [of the book] and assume this is what you’re going to get – veiled women. But after flipping through, you soon realise that what you’re looking for is not there. I want you to be confronted with your own desire and the frustration that comes from not finding what you’re looking for.”

This strategy positions The Fold in dialogue with Afshar’s broader practice. Speak the Wind deals with ritual, possession and the unseen – winds believed to inhabit bodies in the Strait of Hormuz, between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. Both projects circle around invisibility and absence, and question how photography can render what is normally unseen. In one case, it is the invisible force of the winds; in the other, the invisible but ever-present colonial gaze. Afshar also draws attention to how such images still shape political life. “The obsession towards the bodies of women, in particular Islamic women, is often used as a symbol,” she explains. “To show the oppression of certain places, or the barbarity of certain places, to justify the bombing or occupation of certain countries.” The female body – veiled, unveiled, disciplined – becomes a site on which power is asserted. Patriarchal forces inside colonised nations use women’s bodies to resist, while colonial powers use them to legitimise conquest.

This double-bind is particularly acute in France, where the veil remains a flashpoint of debate. Afshar links this fixation to a deeper historical wound. During the Algerian War of Independence, Frantz Fanon noted that women’s veils could conceal weapons; bombs were transported into French venues by women, little suspected by the authorities. For Afshar, contemporary bans on veils in France may not simply be about secularism or feminism, but about a lingering trauma rooted in that revolutionary history.

Afshar describes her project as “a forensic investigation of the psyche of de Clérambault”, but adds that he is more than an individual; he embodies the colonial gaze. To step into her installation is, she suggests, like stepping into his mind. “In Being John Malkovich there’s a door that lets you see the world through his gaze,” she says. “When I started making the work I was thinking about that film a lot.”

The installation opens with a short animation of de Clérambault’s death, his body slumped in his fabric-filled room, gun by his side, mannequins draped in hayek around him. From there, viewers enter a mirrored corridor in which archival images are printed on panels. As you look, you also see yourself reflected into their surfaces, implicating your own gaze in the act of looking. A sound installation deepens the immersion, while video works present interviews with five scholars dissecting de Clérambault’s persona from different perspectives.

“Such archives are never about the subject. They’re about the purpose the colonial photography was serving – to classify, to justify colonisation.” This is why theorists such as Ariella Aïsha Azoulay have described the camera’s shutter as an “imperial shutter”, summing up how, from the beginning, photography served empire.

Afshar does not let the archive rest silently in its drawers. By fracturing it further, reprinting it, and forcing audiences to confront their own expectations, she turns the colonial gaze back on itself. The Fold is not simply about de Clérambault or a past gaze, it is about the structures of seeing that persist today in politics, the media and our own imaginations.

When Performing the Invisible closes, The Fold will enter the collection of the Musée du quai Branly, where future researchers may return to it as part of the long conversation around archives, images and power. “It makes me very happy to know that it will be part of that history,” Afshar says. “Someone else could come and have a dialogue maybe 100 years later.”

Her work raises a final, unsettling question: what do we really see when we look at images of veiled women? Do we see the subjects themselves, or only our own projections staring back? Afshar’s answer is to hand the question to the viewer, mirrored in the folds of fabric, fractured across thousands of tiny fragments.

Performing the Invisible is on show at Musée du quai Branly, Paris, until 25 January 2026. The Fold is published by Loose Joints