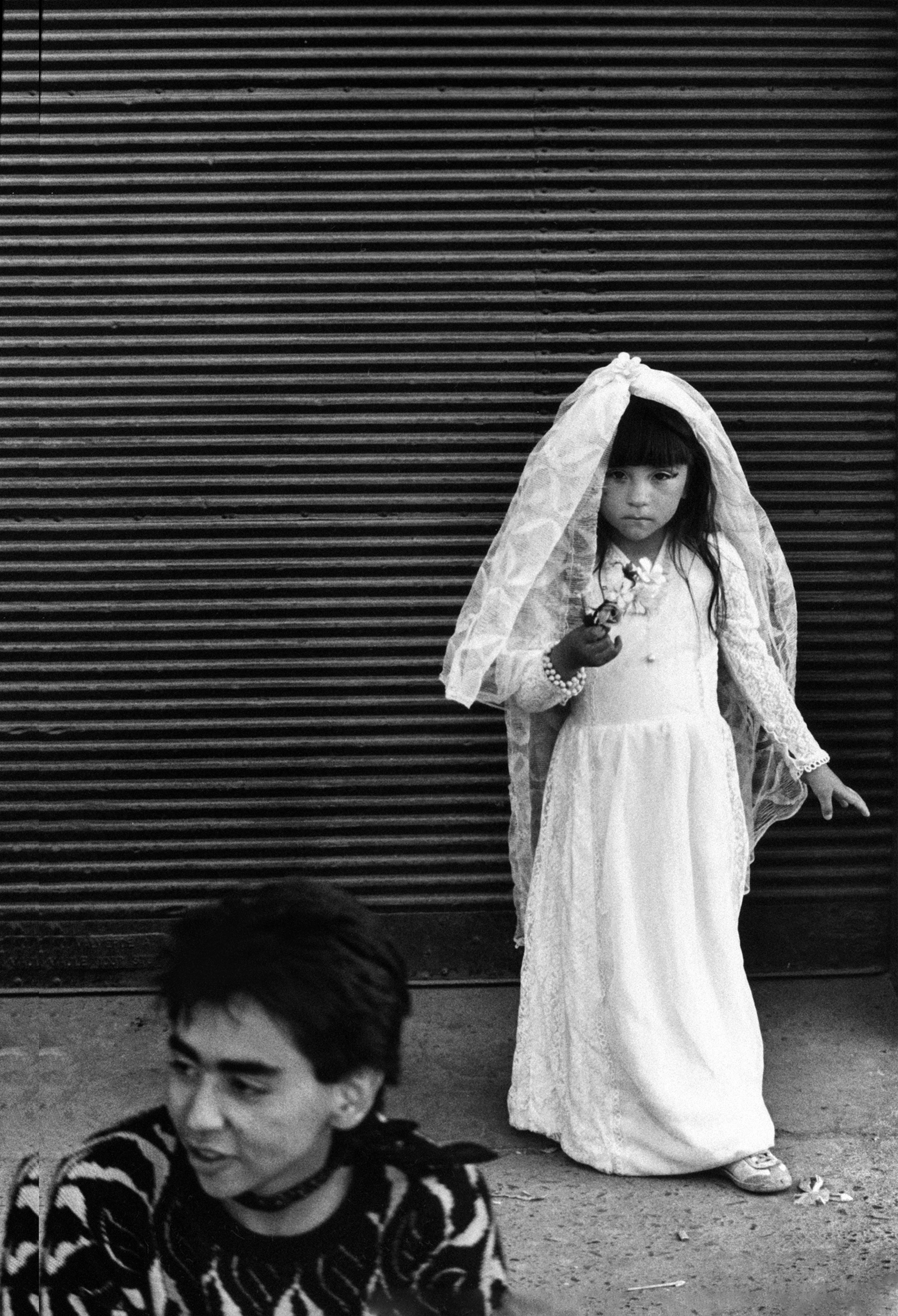

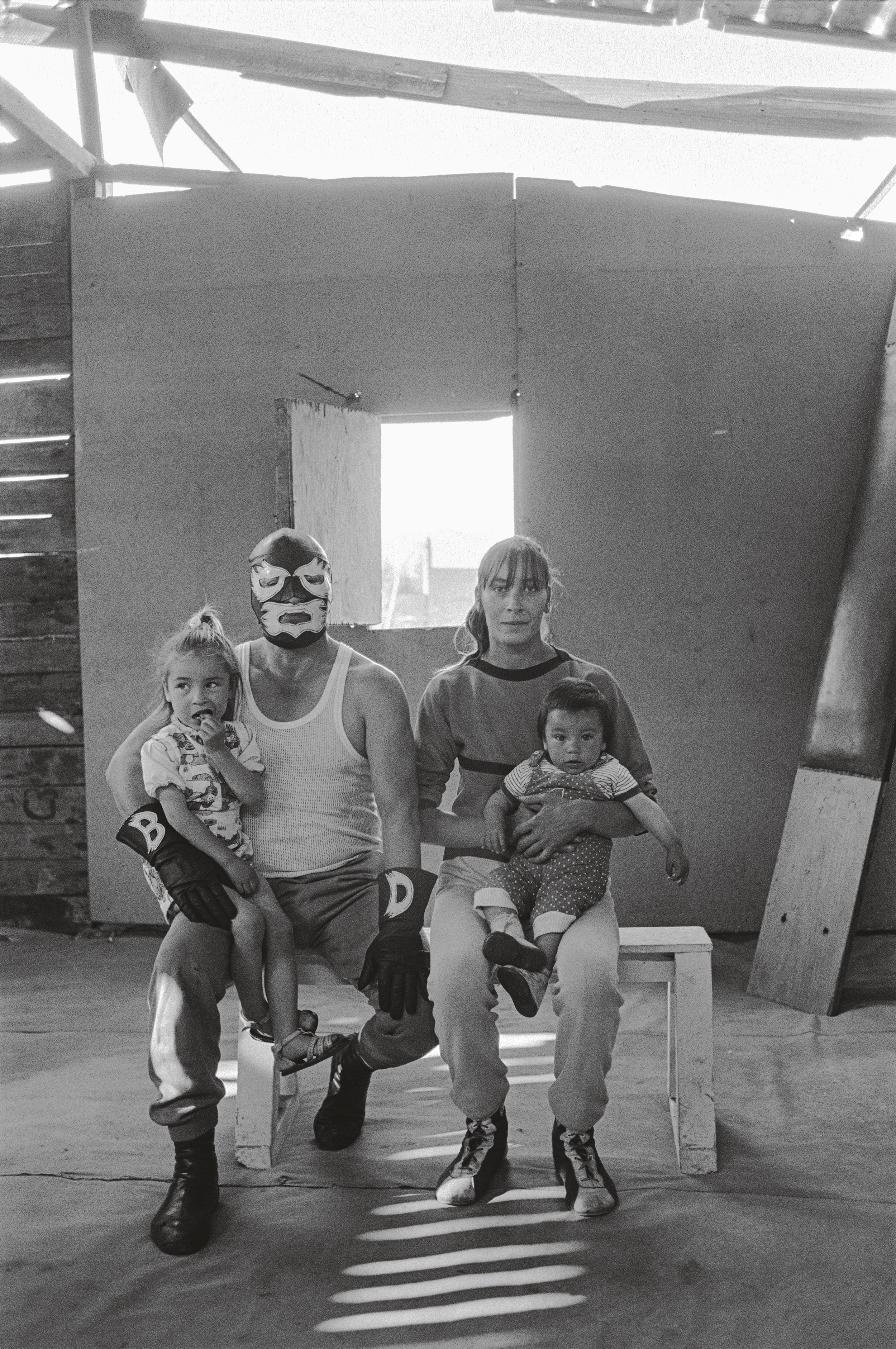

All images © Paz Errázuriz

At MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, Dare to Look brings together over four decades of work by the Chilean artist

In the summer of 1986, Paz Errázuriz began a monthly portrait series, photographing her son Tomás against an exterior wall of their home in Santiago, Chile. The project lasted four years, and in 2004 Errázuriz made it into a video piece titled Un Cierto Tiempo (‘a certain time’), currently on display as part of Paz Errázuriz: Dare to Look, at MK Gallery in Milton Keynes, which opened in July. “It’s a hopeful piece about change,” says the gallery’s Head of Exhibitions, Fay Blanchard, recalling the symbolism between the teenager’s evolving appearance as he nears adulthood, and the country’s own subsequent transformation, from a dictatorship to a democracy, following the 1988 plebiscite. “I think it’s really important [as a mirror of the times].”

Blanchard’s introduction to Errázuriz, like many peoples, was via the more prominent La Manzana de Adán (Adam’s Apple), first at the Venice Biennale in 2015 – where the photographer represented Chile alongside the artist Lotty Rosenfeld – and later at the Barbican’s 2018 exhibition, Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins. Made in collaboration with, and documenting a community of, LGBTQIA+ sex workers at brothels in Santiago and Talca, the series was shot between 1982-87 and focused on Mercedes Paredes Sierra and her children, Evelyn/Leo-Leonardo and Pilar/Keko-Sergio (the names were used interchangeably, while Errázuriz’s photographs capture both their female and male identities).

Living on-site with the family alongside her friend, the journalist Claudia Donoso, Errázuriz’s record of their lives at this time is one of striking tenderness and considered solidarity – largely at odds with the wider sentiment of the country, when violent persecution was a common tool of the regime. “Taking a photo is extremely intrusive and letting oneself be photographed is highly courageous,” explains Errázuriz, now 81, on a nearby wall text, acknowledging the trust of her subjects. “There is a commitment between the two parties, a sort of pact that must not be betrayed.”

“It’s a hopeful piece about change”

Despite being awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship during this period (in 1986, making her the first Latin American woman to receive the accolade), the work wasn’t exhibited publicly until 1989, with a book published Zona Editorial the following year featuring testimonies from the series’ protagonists, collated by Donoso. It attracted little fanfare at its launch – selling just one copy – however in 2013 the work was acquired by Tate, and a revised edition of the book was later released to include more images (at the Barbican, notably, a photograph of Evelyn fronted much of the exhibition’s marketing materials).

Earlier, in 1973, prior to the coup d’état that inserted General Pinochet and the severe 17-year dictatorship that followed, Errázuriz had been working as a primary school teacher. When her home, shared with her two young children, was raided by the military just days after Pinochet had seized power (owing to her being part of a union), she began to focus instead on photography (previously a hobby, picked up while studying in the UK), and the creation of a body of work foregrounding those otherwise at risk, both physically and of being forgotten. Shared by several other photographers, this perspective and desire to distribute an ‘alternative’ image of Chile, additionally saw her co-founding the Chilean Association of Photographers (AFI) in 1981.

“For me, it was a form of activism,” reads a further wall text from Errázuriz, alluding to the harsh political landscape against which much of her work was made, and which all ultimately engages with, albeit with varying distance. “Photography let me participate in my own way in the resistance waged by those who remained in Chile. It was our means of showing that we were there and fighting back.”

![9. Paz Errázuriz, Dormidos V [Sleeping V], 2000, from the series Los dormidos [The sleeping], 1979-1980, Digital ink print on paper, © Paz Errázuriz. Colecciones Fundación MAPFRE](https://www.1854.photography/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/9.-Paz-Errazuriz-Dormidos-V-Sleeping-V-2000-from-the-series-Los-dormidos-The-sleeping-1979-1980-Digital-ink-print-on-paper-©-Paz-Errazuriz.-Colecciones-Fundacion-MAPFRE-.jpg)

With Dare to Look, which marks only her first major solo show in the UK, upward of 170 photographs are presented, made over a 40 year-period (some of her more recent projects include Dolls: Chile-Peru border from 2014, and Blinding light, made between 2008-10). “Protest, women’s rights, ageing bodies, minority ethnic groups, gender, disability, and ideas of resistance and change – they’re themes that are ever present,” notes Blanchard, highlighting the significance and foresight of the photographers’ practice.

“Her work isn’t done in isolation,” Blanchard continues, “she’s usually working with a scientist, a poet, a journalist, a linguist, and we wanted to bring their voices into the exhibition, as well as some of the critical reception, bringing in nuance. There are ethical issues, for example a series in a psychiatric hospital [Antechamber of a nude, 1999] and Errázuriz doesn’t shy away from that; she wants to acknowledge that, and the tension there to do with consent. She’s incredibly trusting, and there’s a confidence – she’s very willing for it to have a life; for people to speak about it and come to their own conclusions.”

Typically working with subjects steeped in politics, the quieter elements of Errázuriz’s photographs can sometimes be overshadowed suggests Blanchard, who spent two years immersed in the work while putting the show together. “There’s so much context, so much subject, when you’re looking in print or digitally, you overlook the formal beauty,” she shares. “You need to really spend time with [the images] to see they’re so beautifully composed. And the work in colour too, is also under recognised – just how extraordinary her work in colour is. Errázuriz says she didn’t know if she was shooting in colour or black and white – film was rare, she had to take what she could get – but I’m not sure I believe her. It is so beautiful in its use of colour, I don’t know if you could do that accidentally.”