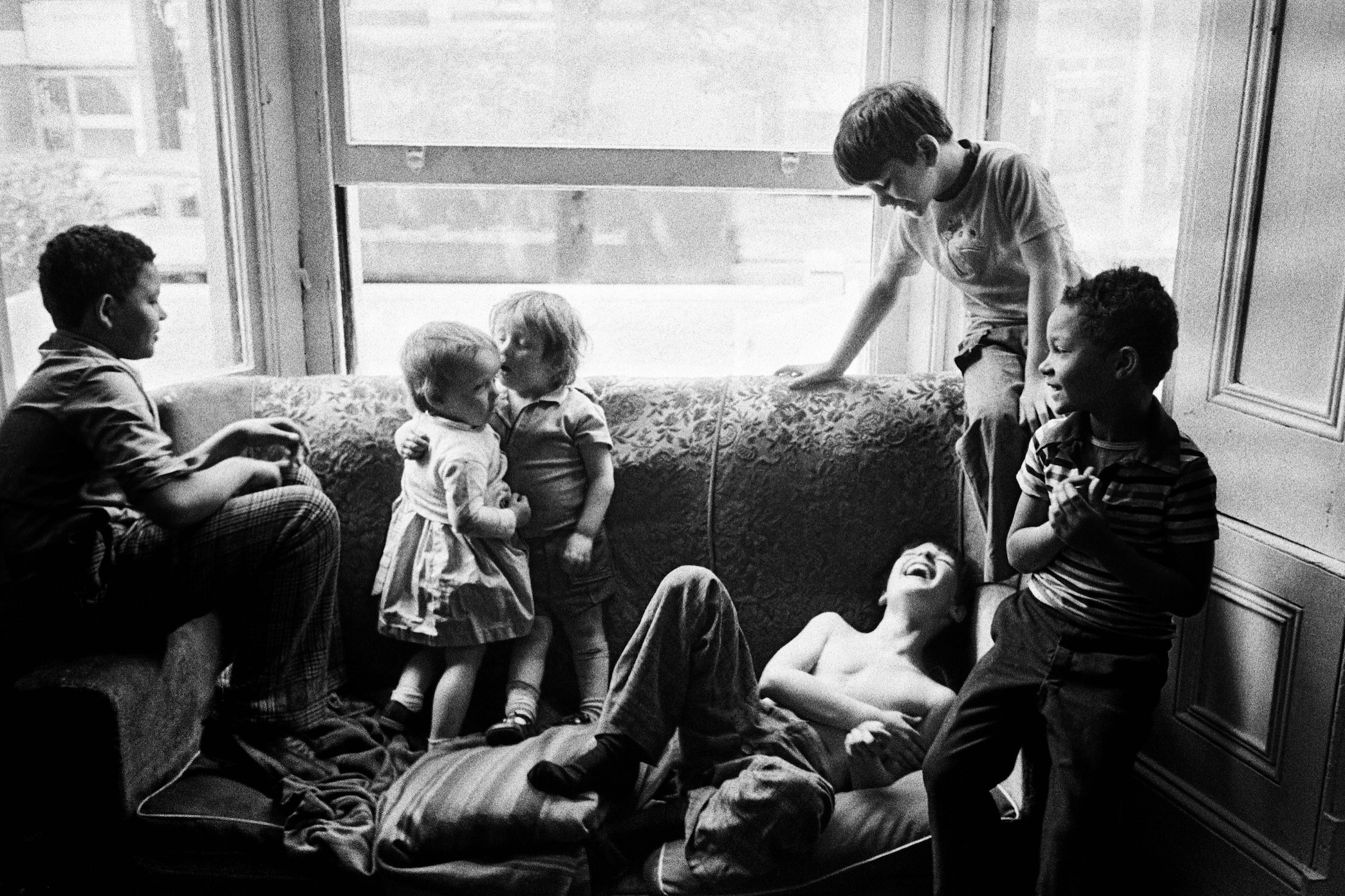

© Markéta Luskačová

Diane Smyth speaks to the Czech photographer about her career between Prague and England and the resistance to being pigeon-holed

Born in 1944 in Czechoslovakia, Markéta Luskačová graduated with an MA in sociology then went on to study at Prague’s FAMU (Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts). From 1970 to 1972 she photographed theatre performances at the Divadlo za branou, then in 1975 left Prague for England. Luskačová shot street markets in London, beaches in Tyneside, everyday life in Ireland, and children – a constant theme in her work. In 1977, she had a son, Matthew Killip. Luskačová has exhibited at institutions such as Side Gallery, V&A, Whitechapel Gallery, Tate Britain, MoMA and the Martin Parr Foundation. More recently, her work was on show at Stills in Edinburgh, where it was accompanied by a book, titled Children, published by Bluecoat Press.

) 2-1 (dragged)](https://www.1854.photography/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/ML-28-Citizen-2000-Girls-in-the-playground-IV-Holland-School-1988-11-2-1-dragged.jpeg)

“Rather than photographing the tanks in the streets, I photographed people’s reactions to the invasion”

Diane Smyth: How did you get into photography?

Markéta Luskačová: It was while I was studying sociology at Charles University, Prague. My first photographs were of pilgrims in Slovakia, and my professor thought I could combine photography with sociology, suggesting my images could be part of my thesis on traditional Slovakian religious festivals. It was during the Prague Spring, a good period in my country’s history – I couldn’t have graduated with this theme a year earlier or later. My finished thesis consisted of the photographs and a sociological text. I realised that, for me, photography opened a profound way of understanding people and life.

DS: You started making images around the time of the Soviet invasion of Prague, 1968. What impact did this event have?

ML: Rather than photographing the tanks in the streets, I photographed people’s reactions to the invasion – the sad and bewildered faces of the citizens, women crying and hugging, people praying, the vigils and funeral processions for youngsters killed by Soviet soldiers. The invasion affected everybody. People who protested against it lost their jobs; many left the country, including Josef Koudelka and my sociology professor.

DS: Prague’s theatres were centres of dissidence, particularly Divadlo za branou. How did you work there?

ML: When Koudelka left, I succeeded him as Za branou’s photographer. Otomar Krejča [the founder and director] staged Sophocles’ Oedipus-Antigone, expecting it to be their final production before the communist authorities closed them, in the aftermath of the invasion. He invited me to exhibit Pilgrims in the theatre foyer, explaining he was trying to convey a similar message with the play as I was with my photographs – people acting on their beliefs, regardless of the consequences. It was my first exhibition. Krejča taught me about the responsibility of the photographer, constantly reminding me that, when their performance ended, my photographs would be the only things left.

DS: Why did you photograph street markets and street musicians in the UK?

ML: I was an immigrant, without any of the social connections that are so important in Britain. Outdoor events were more accessible. But I started going to the markets simply because I needed to buy things as cheaply as possible to survive. I took photographs while shopping. I wanted to remember the faces of the traders and their customers, their vivacity and their fortitude. By photographing them, I was also speaking about myself.

ML: Photographs of children permeate my work. At home I have pinned up a quote from Limping Pilgrim, by Czech writer and painter Josef Čapek, who is more eloquent than I could be: “I love children very much and I respect them greatly. I am overwhelmed by their divine urge to scoop up life and to be loved… [their] joyfully wild need to be alive, the power of growth acquiring and conquering life endowed with astoundingly optimistic energy, enabling them to stand to the absolute supremacy of destruction that rules over all things.”

DS: Have you ever felt pigeonholed as a woman photographing children?

ML: No, it was always known I photographed other subjects. But it helped me make

a living. Men, I was told, did not like photographing children, and good picture editors know there is a better chance of good work if photographers like what they photograph. But a few curators were always too busy to come if I invited them to see my photographs of children. I feel lucky that Ben Harman, director of Stills [at the time of Luskačová’s exhibition], did not consider the subject unimportant, and I could exhibit my photographs there.

DS: Was it difficult to keep photographing after becoming a mother?

ML: Yes. Being a single mother, a freelance woman photographer and an immigrant was not easy. [But] I didn’t give up. I kept taking my own pictures that nobody commissioned or paid for, despite life’s difficulties.