All images © Sebastián Bruno

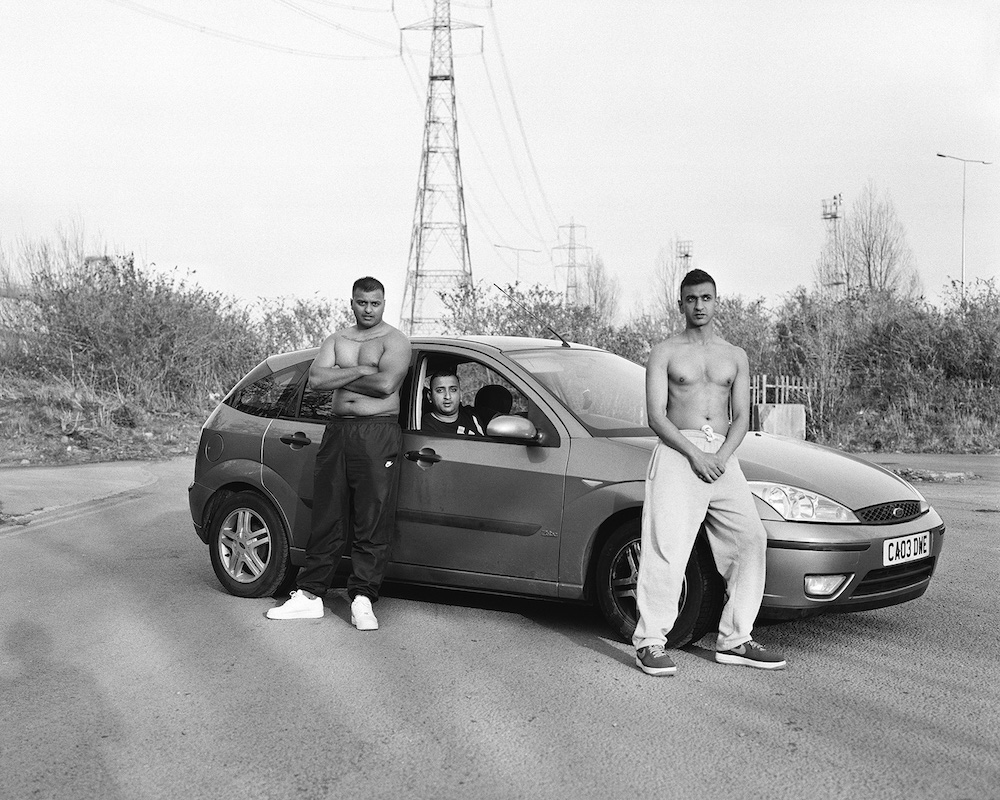

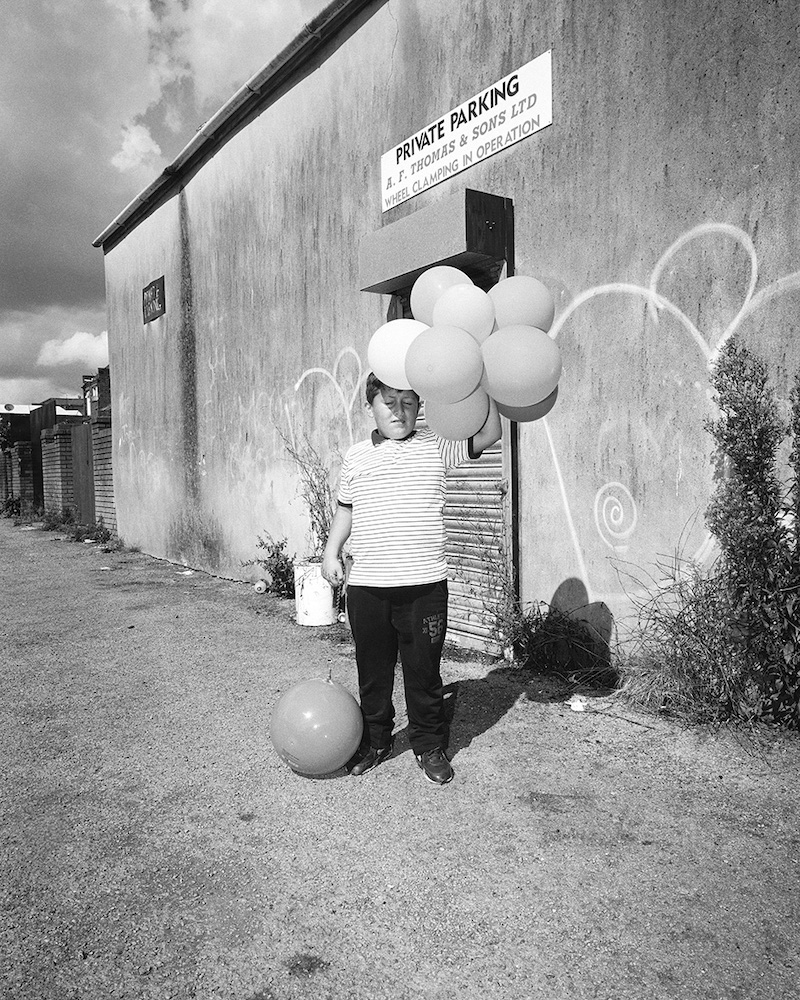

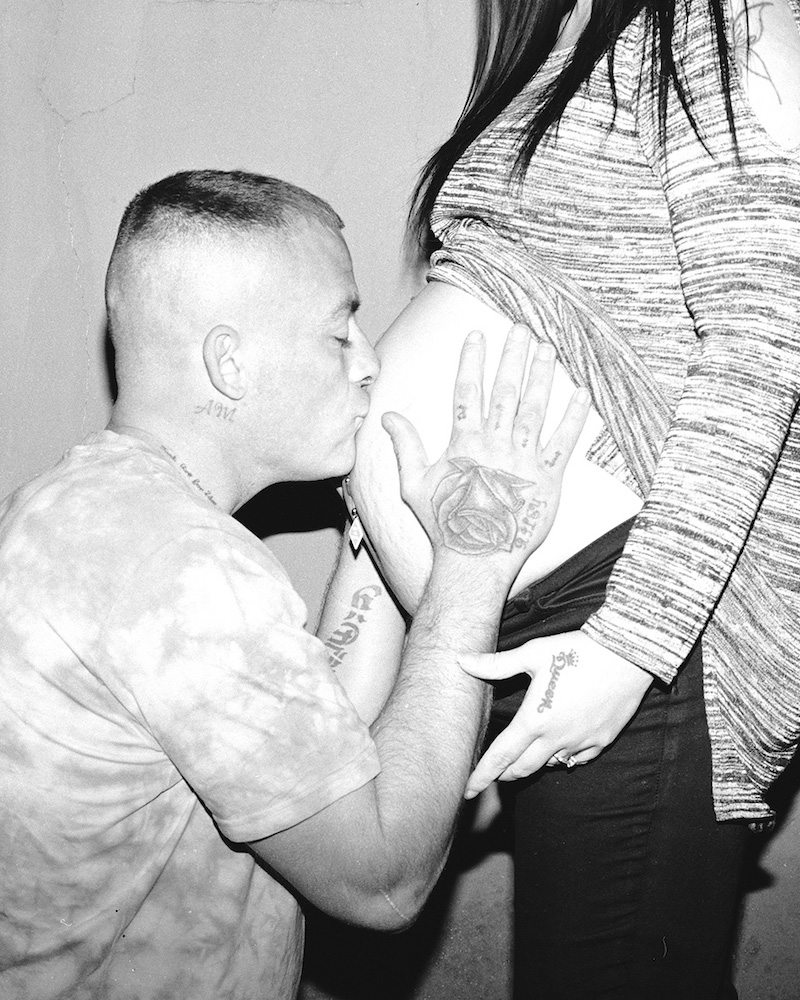

Sebastián Bruno’s series Ta-ra is the result of a decade spent living and working in Wales, a country he initially planned to visit for six months

In 2010, Sebastián Bruno arrived in Cardiff from Argentina, expecting to spend six months living and working there before travelling on elsewhere in Europe. But while in Wales he fell in love with photography, and made the country his home for more than 13 years. His latest body of work, Ta-ra – which was awarded the Mallorca Prize for Contemporary Photography 2022 and published in book form by Ediciones Anómalas in summer 2023 – represents a decade’s worth of Bruno’s photographic experiences in Wales, and provides striking insights into its people, culture, communities and collective psyche.

Aaron Schuman: How did you first get into photography, and how did you first find yourself in Wales?

Sebastián Bruno: When I was 14, I started carrying around a little camcorder – I was always filming, and wanted to study cinema. I even attempted to go to university for it in Argentina, but my head was somewhere else. Then in 2010, when I was 20, I came to Cardiff because my cousin was living here. My plan was to stay for six months, just doing odd jobs and working in restaurants, and then go somewhere else. But when I got to Wales I felt more focused and centred, and ended up staying longer than expected. After working in the UK for a year, I received a small tax refund, and used it to buy a cheap DSLR and to sign up for some photography courses at Ffotogallery in Cardiff. The person who was running the courses there encouraged me to apply to university, so I did, and in 2012 I started studying on the BA documentary photography course at the University of South Wales, Newport.

AS: That course has a long and influential history – what was your experience like there?

SB: The course, although now in Cardiff, has been renowned for 50 years, and has maintained the same ethos since its founding in 1973. This, together with a responsibility to instil in students the importance of developing work that critically engages with the world, is what keeps it relevant. Since graduating in 2015, I’ve continued my relationship with the course, and contribute by teaching, trying to pass on those same values, and the love for documentary photography that I was infected with while studying there. Everything I am, I owe to that course.

When I arrived, I already had a strong social and political consciousness – I’d always felt that I had something to say, but I didn’t know how to channel that energy and those thoughts. And I didn’t have any knowledge; I didn’t even know what ‘documentary’ was properly, I just assumed it was photojournalism or street photography. So I spent the first year trying to absorb everything. I discovered so many photographers, the projects they’d made, and the different visual languages they used.

Then, during the second year, I came to the conclusion that to be able to make work, I really needed to feel something about a subject, and to respond to place and people. At the time I was working as a waiter in a restaurant in Cardiff Bay, and I was notorious for providing either the best possible experience or the worst, depending on how much I liked the customer. It happened that the majority of the customers that I particularly disliked – and this dislike was always mutual – would frequently go to a bar upstairs, right above the restaurant. When I realised that I wanted to photograph things that made me feel something, I said to myself, “I should go and take pictures in there”. I thought that the best thing I could do would be to spend my evenings in that bar with them.

While I was doing that, I was also consuming a lot of photography made in the UK during the 1980s, which I found ideologically compatible with this project. So I started to work with one camera – a Mamiya 7 with a Vivitar 283 flash – because I wanted to borrow some of those aesthetics and find my own way around it.

“In all the places I’ve lived, I’ve been involved and embedded in the community. But when I speak, I’ve never made an effort to have a softer accent; I’m a foreigner, and that’s what differentiates me”

AS: Which photographers were you specifically drawing inspiration from?

SB: Martin Parr, Paul Reas, Anna Fox, Paul Graham, and so on. I was using the same set-up as them, shooting in colour using a wide-angle lens and flash. It was kind of a visual experiment to understand how I saw things and respond to places, in an attempt to find a way of working that suited me, and how I might own that aesthetic. The flash gives you the opportunity to see the world differently, and to transform the most ordinary things into something exceptional. I was also discovering the work of Weegee and Diane Arbus, and then realised that I wanted to make photographs in black-and-white.

AS: Was your cinematic background also informing your work?

SB: I think that was more in terms of creating a sense of narrative, and learning how to direct the people that I was photographing – asking them to pose in a certain way, or to be as expressionless as possible, which I think I got from the films of Aki Kaurismäki or Robert Bresson. I wanted the kinds of expressions that make everything neutral and ambiguous, from which a certain tension can arise. There’s a lot of humour in that as well, but a humour that’s found in the ordinary. I didn’t want to give the viewer any certainties, but instead to see what the photographs did to them.

AS: Your new book, Ta-ra, draws from a decade’s worth of work made in Wales, from 2013 to 2023, so some of the photographs included were made during this very early period.

SB: Yes, the earliest pictures in Ta-ra are from that time, when I was still at uni trying to discover myself and my approach to photography. There’s a portrait in the book of a man with a dishevelled pompadour – that’s at the Porthcawl Elvis Festival. I took that picture in black-and-white, and was like, “Wow, this is where I want to take my work”.

AS: Earlier you mentioned Weegee and Diane Arbus. Nancy Newhall once referred to Weegee’s photographs as “extraordinary psychological documents”, and John Szarkowski described Arbus’ pictures as being “concerned with private rather than social realities, with psychological rather than visual coherence”. In Ta-ra, were you also more interested in exploring and emphasising the ‘psychological’ possibilities of photography, rather than the ‘social realities’?

SB: Well, that partially comes from the use of flash, but it also comes from always seeing a place with a degree of detachment, as a foreigner or otherwise. In all the places I’ve lived, I’ve been involved and embedded in the community. But when I speak, I’ve never made an effort to have a softer accent; I’m a foreigner, and that’s what differentiates me. I can have a familiarity with a place and its people, and at the same time always have a degree of detachment, because I don’t feel the need to hide my cultural background or references. It’s not about adapting to a place, it’s about using my own perspective to incorporate the elements of the place where I’ve chosen to live – what I like and dislike – into my own vision of it, and being able to be both affectionate and critical at the same time. Again, there’s an ambiguity there, in that you have both sides.

AS: What do you find particularly unique about Wales, and what are you specifically trying to express about the people and the place in Ta-ra?

SB: If you look at Chris Killip’s In Flagrante, at the people in those pictures, everything has been taken away from them, in front of their eyes, and you see their sense of desperation. They’re not letting things slip away from them – someone is coming and taking everything away, and they can’t do anything about it. Alternatively, in my images, I think a sense of numbness prevails. It’s like there’s nothing left to be taken away. With everything that’s happened in Wales and the UK – even since 2013, with the implementation of the austerity policies, and then Brexit and its consequences, and then the pandemic, and then the current economic crisis – what remains is this profound sense of numbness.

AS: Do you feel that this ‘numbness’ is a kind of psychological response or emotional defence mechanism, which is particularly prevalent here as the result of these repeated traumas?

SB: Yes. Also, when I was making the work, I myself was also going in and out of that same sensation of numbness. Even though these pictures were made specifically in Wales, I think this is something that is happening throughout the whole country, in working-class communities and elsewhere.

You’ve also moved to the UK from another country, in your case from the United States, so you must also see the social divisions that are here, and recognise how the class structure is always present, and so systematically embedded within this society. To me, this is unbearable; I can’t stand it. I try to treat everyone on the same level and with the same respect. I don’t make any differentiations if I speak with a lord or a person on the street, I treat them the same, and that’s how I expect to be treated. It’s just common sense. So I find the levels of injustice and inequality that exist here unbearable.

Of course, I don’t come from a perfect land. I come from a place where there is extreme polarisation – 40 per cent of the population of Argentina is now living in poverty. But when you think about the UK, and all of the policies that were implemented in the 1980s by Thatcher and the neo-liberal movement, you realise that they may have actually won by successfully destroying the sense of community in a lot of places. And that’s why there’s not just a numbness, but also a sense of profound solitude within this work.

AS: So Ta-ra is definitely more of a ‘psychological’ rather than a ’social’ document?

SB: I’m not trying to redefine the place itself, or impose my ideas onto these people – it is what it is – but these were the things that were driving me when I was making this work. As photographers we have to accept that our medium is subjective, that within our work there’s always the influence of who we are, how we feel, our cultural background, and everything else we bring to a place. I don’t actually know how much of my own psyche or psychological state is in there, but that happens all the time with photography – there’s always a degree to which we impose ourselves onto the people, places and things we photograph. We are working with the real, but in a way we are also borrowing these things for our own agenda. That’s why it took me so long to come to terms with this work, and to realise that the ideas behind it were actually very simple – that it’s about how I was discovering and responding to a place at the same time.

“This project has probably been the most difficult for me to edit – it took me a long time to realise that I was responding to the place emotionally, and that there was no need to over-conceptualise it beyond that”

AS: In ethical terms, how do you deal with this issue? How do you explain to the people you’re photographing that your own perspective or agenda will inevitably play a role in how they will be portrayed?

SB: Of course, it’s very difficult to explain all the intricacies of this to someone in a few minutes – and in this work in particular, many of my interactions with people were ephemeral encounters. I may have met them once and never encountered them again. But I always give people my contact details. For example, there’s one picture that I really love, of two girls – one of them is about 10 years old, and the other maybe 14. It’s one of my favourite pictures, but before doing anything with it, I got the contact details of their father, and I wrote him an email, and then another, and then another. I sent him the picture and said, “This is one the best pictures that I’ve ever made, and it would be great if you could give me a call or send me your number. I would love to talk with you, and give you a print.” And nothing – he never got in touch. If someone does get in touch I get back to them; if they want a print, I give it to them.

AS: During the making of this work, how did you decide where to photograph? What specifically were you looking for?

SB: This project came about because I was just shooting all the time, for the pleasure and sake of making pictures. I think it’s important to understand the place where you are. Like any photographer, I could be parachuted into a faraway place and find things that interest me, but I’m not driven by exoticism. I much prefer to be in the most ‘boring’ or familiar places, creatively that’s where I find a challenge. Trying to elevate something that is seemingly insignificant, and trying to identify remarkable things within the ordinary is a great challenge.

So really, it just depended on where I was, and what I was doing. Ta-ra is almost entirely made in the south of Wales, predominantly in towns and cities, rather than in rural places or the bucolic countryside. I really wasn’t trying to target a particular demographic, or certain class or anything. I was just looking for people who I was drawn to. But what I was always trying to do was to decontextualise everything, so that the context for each picture would be informed by the other photographs, the edit, and the sequence, in order to create an almost imaginary sort of space. This project has probably been the most difficult for me to edit – it took me a long time to realise that I was responding to the place emotionally, and that there was no need to over-conceptualise it beyond that. I started with 250 prints, and then slowly tried to make sense of it, refine it, and find the common factors that brought everything together. That way, the work itself collectively builds a place of its own.

AS: What do you think your Argentinian perspective brings to this place that might differ from that of British photographers?

SB: I always feel like I’m some kind of hybrid, because the education I received and so much of the information that I consumed came from the UK. But then I have this set of cultural references that comes from Latin America and Europe. So there is something different there, but I don’t know exactly what it is. Sometimes I feel – maybe you notice it too – that in the UK there is a certain lack of spontaneity within life in general. You have to constantly generate new adventures for yourself if you want to be challenged by what’s happening around you. When I was beginning to make this work, I felt this need to ‘feel alive’, so I went to what was supposed to be the most ‘notorious’ neighbourhood in Newport. And indeed there were people on the streets all the time, and things were spontaneously happening everywhere, and it was great – and, as in Argentina, there was a strong sense of community. When I was walking around, some kids came up to me, wanting me to take their picture, so I took it, and then immediately said, “Let’s go talk to your parents now.” So I went to talk to the parents, and they ended up inviting me into their houses. I made lots of pictures with these two families – in fact, that’s where I made the portrait of the baby who’s all wrapped up.

AS: You spent 10 years making this work. How did you know when the project was complete?

SB: Because I didn’t want to make any more pictures. Maybe I didn’t exhaust all the possibilities, but I felt like it was time to move on. As I said before, the reasons I ended up in Wales, and staying for so long, were chance and entirely circumstantial. It wasn’t something I’d planned, it was just the way my life organically happened. And I’ve reached a point now where I don’t want to make any more work here, but in a nice way; maybe that’s why the book is called Ta-ra, which is a local expression that is commonly used to say a friendly goodbye.

When you become part of a place, you learn to both love it and hate it, but over time more and more things have made it harder for me to live in the UK, and I don’t want to become any more cynical and angry – then it’s really not fair on the people I’m photographing. So I guess that I don’t want to make any more work here because I don’t feel the same way that I once did, and the project might become too dark, or turn into something that it wasn’t intended to be.

AS: Despite this, do you still feel an affection for or connection to Wales, having spent so long living and working there?

SB: Of course, all of my adult life happened here. It’s home – it’s so familiar to me now, it’s what I know, and it’s easy for me to make work here. The people have given me so much. To be honest, I’ve always been fighting with myself here, because I never wanted to make work specifically about Wales, and still I ended up doing it – twice in fact, considering that I also just published another book, The Dynamic, which is about a local Welsh newspaper.

I really do love the history here as well, especially considering that many of the biggest achievements of the UK’s working class started in Wales. The National Health Service was modelled on the Tredegar Workmen’s Medical Aid Society, which was set up by Welsh miners in the 19th century. Before that, you had the Chartist movement in the 1830s, and then you also have a lot of people who went to fight against Franco and fascism during the Spanish Civil War, then you have the Miners’ Strike [1984–85]. In certain communities there is still this strong sense of socialism, which people are born with. It’s by no means a socialist utopia, but those kinds of values are embedded within the culture and remain in the people. Even if they may have lost the battle, there is a sense of solidarity, openness and welcoming energy; it’s still here. So I will always love it, but I have to say ta-ra.