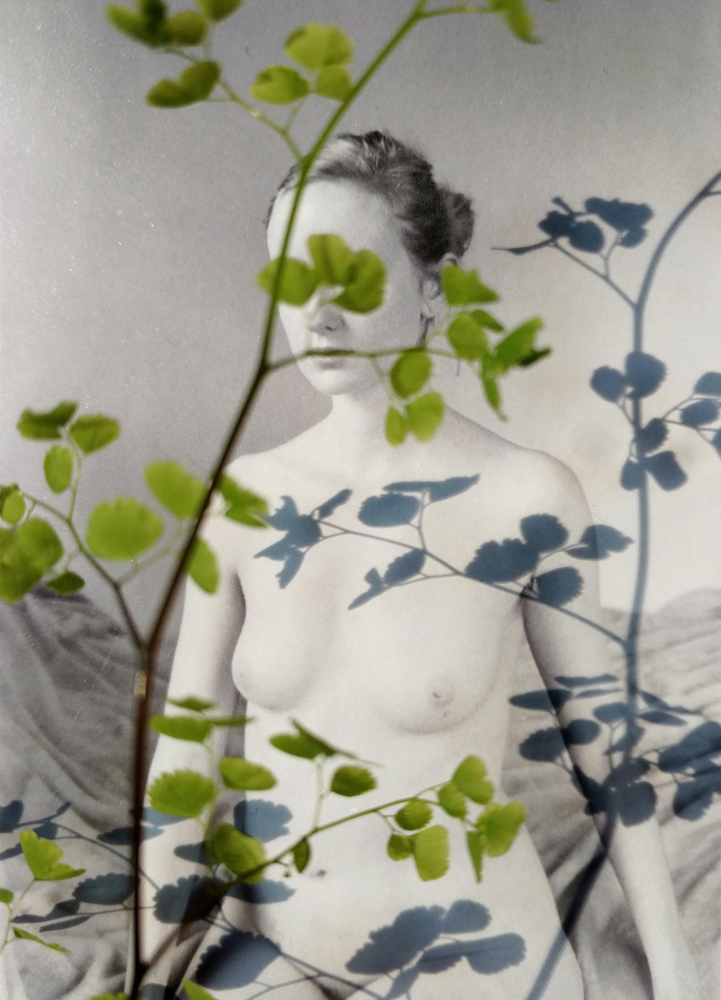

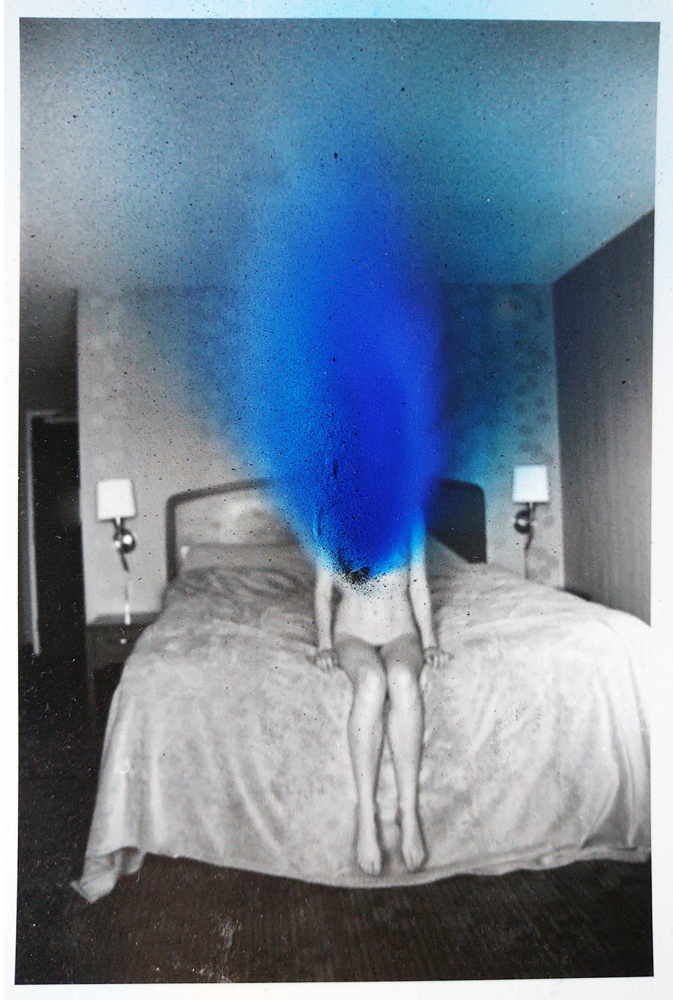

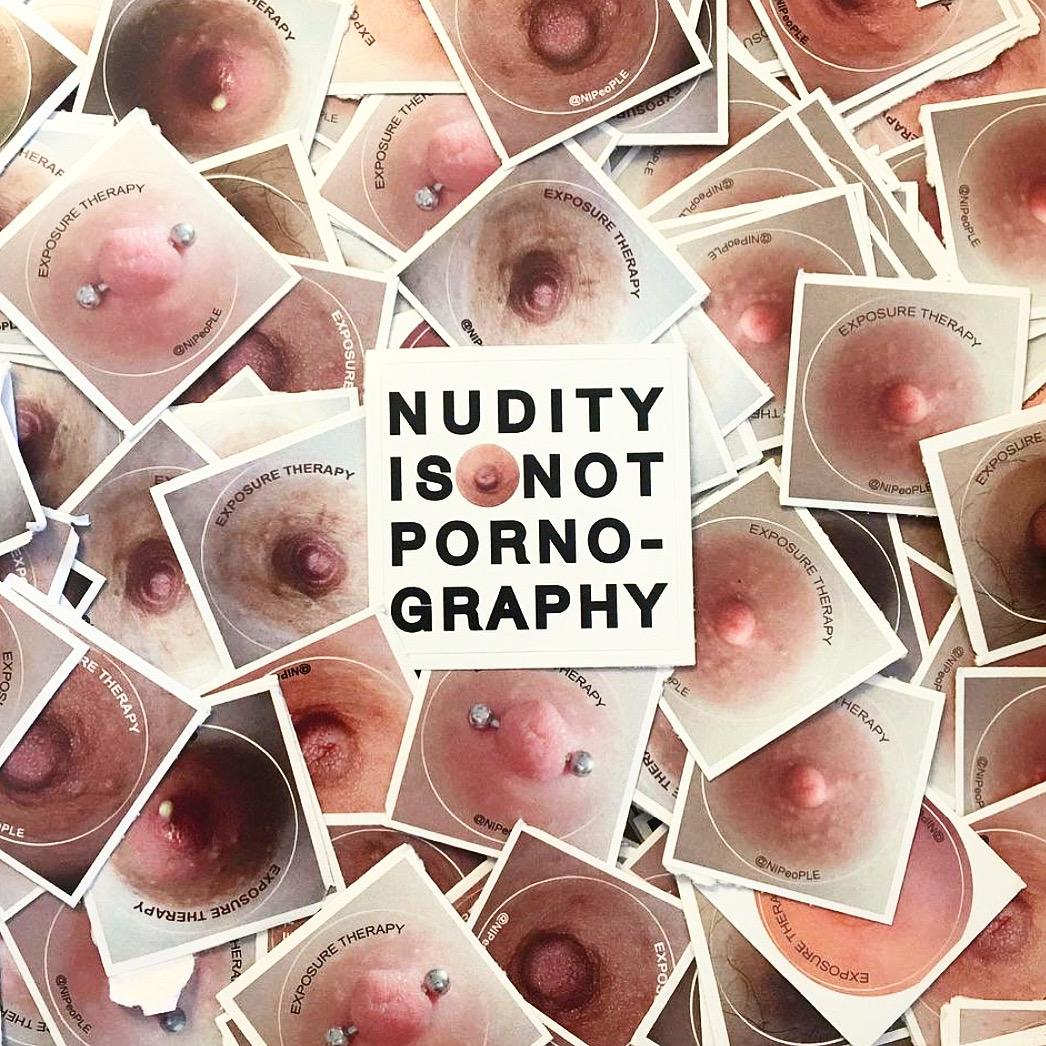

Stickers from the nipple-equality project Exposure Therapy © Emma Shapiro. All images courtesy the artists

Women’s nipples are censored online while men’s are not, a state of control that has worrying repercussions for artists and marginalised groups

Coined in nascent internet days, the phrase ‘pics or it didn’t happen’ has persisted as a prescient motto of the Instagram age. Like its antecedent, ‘if a tree falls in a forest…’, which predicts obscurity for those not witnessed, this saying equates online activity with actual existence. Since the creation of Instagram in 2010, our lives have become intertwined with social media presence; it has become a tool, a community, and a lifeline for creatives, who have good reason to rely on it.

Natural disasters, financial crises, political turmoil and a pandemic have all contributed to our dependence on a virtual place where we can connect with opportunities and share work. Unfortunately, many artists have found themselves unable to establish that presence, as private companies play the role of arbiter of art and success. For these artists, often photographers, who suffer personal and professional hardship from suppression, erasure and censorship on sites like Instagram, ‘pics or it didn’t happen’ rings ominously true.

My first experience with art censorship was not on social media, it was at a Walmart supermarket in rural US. As I waited for a set of self-portraits at the photo desk, the clerk excused himself and a manager replaced him. In a voice loud enough to alert surrounding customers of my indecency, I was told that my prints would be destroyed and that “we usually call the police in this situation”. Genuinely surprised and more than a little confused, I pressed the manager who had threatened me, asking why. Eventually, the answer was, “It shows your nipples”.

After witnessing my artwork reduced to illicit material for the mere fact that I was a woman and my nipples were showing, I was struck by the sheer inequality of the premise. If a man had taken the same self- portraits he would be walking out with them in his hands, whereas I walked out with only anger and shame. Stalking back to my car, I devised my revenge plot: I would put my nipples everywhere.

One nipple sticker at a time, I would prove that a nipple alone is not just harmless, but genderless. The idea was amusing, serious and popular, and soon it would acquaint me with the boundless joys of art censorship on social media. As post after post was removed for that very same ‘it shows your nipples’ rationale, I found that my skirmish with content moderation was just one battle in a long war over nudity and women’s bodies in art online, a war that has destroyed far more art and artists than any prudish Walmart manager could dream.

“If a man had taken the same self-portraits he would be walking out with them in his hands, whereas I walked out with only anger and shame. Stalking back to my car, I devised my revenge plot: I would put my nipples everywhere”

Let the fight begin

The first battle began in 2008, when a Facebook group of new mothers grew sick of their photos being removed for ‘pornography’ and organised a ‘Nurse In’ at the company’s California headquarters. With chants, songs and breastfeeding both in person and online, the ‘Lactivists’ took a powerful first shot at Facebook’s treatment of the female-presenting body.

From the 2008 protest to 2014, Facebook slowly allowed more breastfeeding images, an increase that coincided with rising support for public breastfeeding in the US. Acknowledging visibility to be an influential factor in public acceptance, the US Surgeon General wrote in 2011: “Although focusing on the sexuality of female breasts is common in mass media, visual images of breastfeeding are rare, and a mother may never have seen a woman breastfeeding.” The coincidence of more visibility on social media and a bump in public acceptance is notable, and suggests that ‘real’ lives are not just reflected online, but influenced by online interactions.

The correlation between visibility and social acceptance is well-documented, and particularly significant for underrepresented and marginalised groups as it can mitigate stigma and push society forward. In the case of Instagram vs Lactivists, giving visibility was simply a matter of listening to users and adjusting accordingly. This ‘win’ for breastfeeding sketched out a potentially simple solution for the treatment of marginalised groups on social media – less discriminatory content moderation and an interest in protecting freedom of expression. Despite this, the battle over the female nipple sans baby and the sexualisation of women’s bodies has proven not so simple.

In the years following, Facebook (now Meta) cracked down hard on all sorts of female-body related content. The inflexibility of Meta’s stance, particularly its anti-female nipple policy, has for years kept artists from changing the narrative around the female body. This has had particularly frustrating outcomes for the photography community, who, despite a heritage of over 200 years, still struggles to be explicitly represented by guidelines that currently state they “allow photographs of paintings, sculptures, and other art that depicts nude figures”, without defining what “other art” means.

With Instagram’s continual rise as a professional tool, the repeated erasure and censorship of these artists has left them with just a few, unsatisfying options: mar their artwork with self-censorship, keep projects off social media, or change their practice to adapt to restrictive guidelines. The end result is a stagnant representation of the art world, limited opportunities for at-risk artists, and entire bodies of work created specifically with gender-based censorship in mind.

Rise of legal issues

Those who complain about discrimination online are often reminded that private companies make their own rules, and until recently that was pretty much true. Over the last few years, however, a worrisome shift is threatening freedom of expression across the internet, and is particularly concerning for artists who have yet to be welcomed on platforms such as Instagram.

Efforts to regulate the internet and control platforms are being legislated around the world. In most circumstances, particularly in the UK and US, these efforts purport to protect children and vulnerable groups by going after CSAM (Child Sexual Abuse Material) and sex trafficking. Noble concerns, but ones that have fed into surveillance and partisan ideology online. Instagram artists first experienced these effects when, around the start of 2021, they began to receive a violation notification of “sexual solicitation”. This new accusation levelled at artwork was more than offensive, it was a signal of something more sinister.

Instagram was responding to pressure from a new US law, SESTA-FOSTA, championed by the powerful conservative organisation NCOSE (previously Morality In Media), which has campaigned against pornography, sex work and same-sex marriage, has supported art censorship and targets women’s bodily autonomy. Now Instagram and other platforms became legally liable for anything users posted, spooking them into purging content deemed even potentially illicit, rather than face penalties. This result, when free expression is hindered in an indirect way, is known as the ‘chilling effect’. Beyond social media, this chilling effect has also resulted in the termination of artists’ websites, online shops, newsletters and payment processors.

Digital-rights groups are sounding the alarm on numerous other impending legal changes, and pointing to the fallout from SESTA-FOSTA as proof of the damage that badly designed and partisan legislation can wreak. Laws that are meant to punish websites for illicit material and surveil users will only push actual bad actors deeper underground and target already marginalised communities, meaning that artists are among the first to be impacted. As digital-rights groups warn of a chilled free expression online, human rights groups are reporting the rapidly increasing rate of art censorship around the world. It is apparent we are seeing a global conservative backlash of anti- sex, anti-LGBTQIA+ and anti-feminist values, and that the online culture we have all grown to depend on is a target.

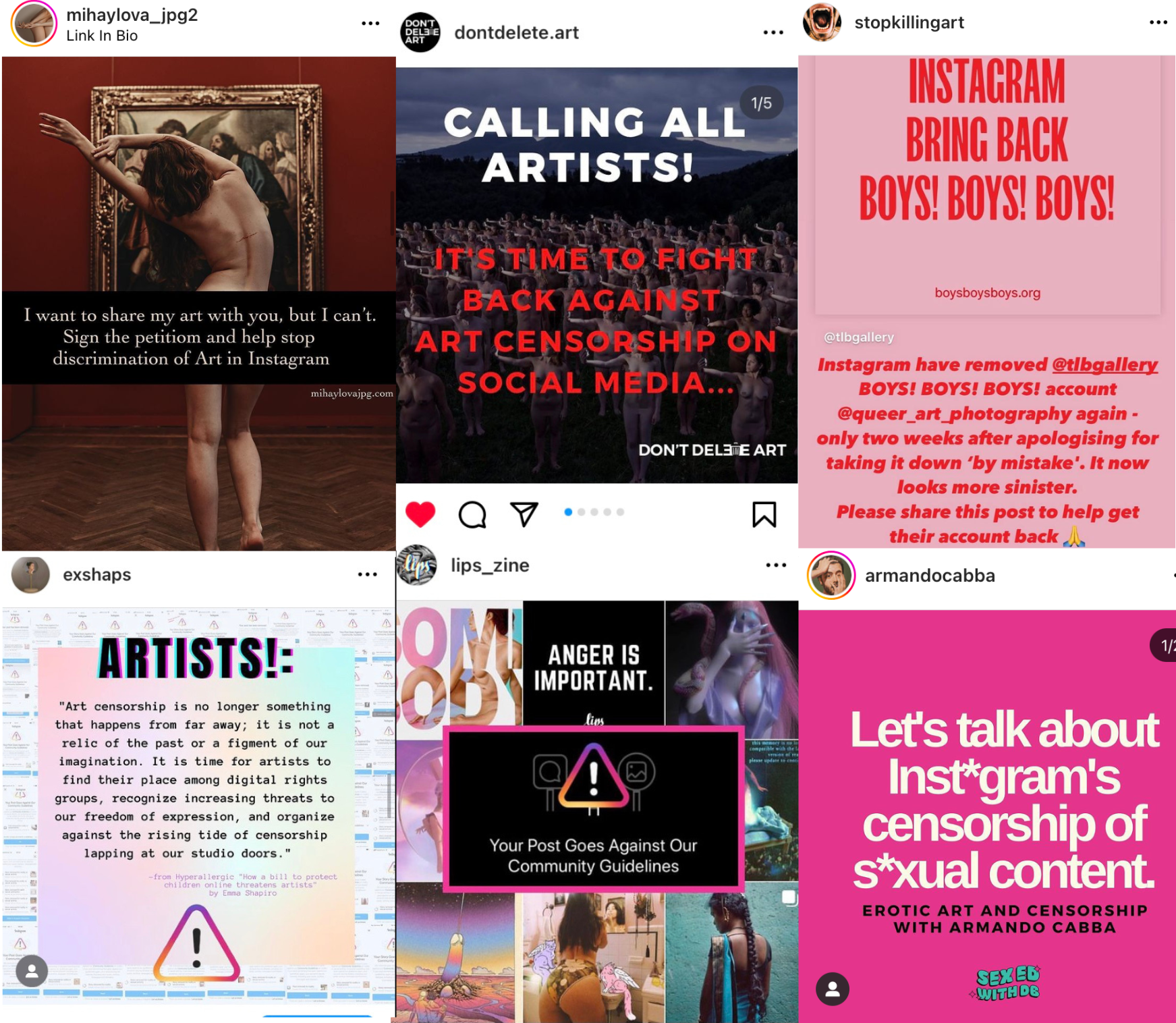

Many of us fight Instagram because we love Instagram – the connection it provides us to opportunities and each other is unparalleled and we want it equally for all. But Meta has only sat down with artists once and any acknowledgment of its mistreatment of artists has been due to public missteps or embarrassment at the hands of the rich and famous. While Instagram’s guidelines correctly note that its policies “have become more nuanced over time”, this progress has been too slow.

Real change in the face of rising art censorship will take the combined efforts of a united art world demanding protection for artists and an end to the “needlessly aggressive gatekeeping” online, as described by anti-art-censorship group Don’t Delete Art (DDA). The DDA manifesto, which aims to bring these voices together, puts it this way: “As social media companies are held to different and changing regulatory standards in the US, Europe and the UK, it will be critical for at-risk artists to be considered and valued as companies adapt.”

With the advent of Instagram and online tools, artists had access to the kind of means and reach they had only dreamed of, an art world finally open to all. In reality though, this access was always obstructed by ingrained sexism and ignorance. Whether torn up in a rural shopping mall or accused of sexual solicitation, art that is restricted by bias will go unseen and artists will suffer obscurity. Through visibility, we can conquer stigma and push our visual narrative beyond the stagnancy we currently risk effecting. Otherwise, if art is not seen, did it ever exist at all? Pics or it didn’t happen.

Emma Shapiro is editor-at-large at Don’t Delete Art, a campaign and resource centre protecting artistic expression across social media platforms