©Supratim Bhattacharjee

Discover the winning images, ranging from a vibrant portrait of a Californian salvage punk to a defiant depiction of a Romanian grandmother

Portrait of Humanity has entered its fifth year, and the unity and resilience that it seeks to promote are more vital than ever. Both are abundant in this year’s winning entries, announced today. From Brazil to Berlin, and from West Africa to Winchester, many come from places of hardship or cultural discord. But they are also much needed expressions of hope.

Judged by a jury of ten industry heavyweights, the three winning series and 30 single image winners will be exhibited at Belfast Exposed gallery and the Indian Photo Festival later this year. The single images will also feature in the Hoxton Mini Press Portrait of Humanity book, alongside a wider shortlist of 200 photographs.

Series Winners

Tatenda Chidora

Tatenda Chidora’s series, If Covid Was A Colour, was shot during lockdown. Rather than recalling that faintly muted angst that many felt at the time, the Zimbabwe-born, South Africa-based photographer’s portraits are a splash of colour and energy. Models stand with curtains made of face masks and lie on deep blue beds of surgical gloves, posing heroically and richly lit as if for a fashion shoot.

“Besides the pain and loss that came with the pandemic, I feel that the human race needs to be celebrated for adjusting to the hefty shift that came with it,” he says. “This body of work goes on to outline conversations that I had with myself and my community and I hope it serves as a place of remembrance in the future as a celebration of how humans stood the test of time.”

Fernanda Liberti

Fernanda Liberti’s Dancing With The Tupinambá focuses on the eponymous Brazilian community that was indigenous to the country before colonial settlers arrived. The portraits feature a Tupinambá woman wearing an elaborate and beautiful feathered cape, sacred to the group but nearly wiped out over the centuries. The people as they are today have faced persecution for centuries. As recently as 2007, the federal police went to their community and burned all of their pictures, says Liberti. “This series is a celebration of existence.”

Lucia Jost

Berlin-based photographer Lucia Jost turns the lens on the women of her hometown in a series of tender portraits that questions the nature of femininity in Germany’s capital. It is “difficult to grasp” who the Berlin woman is, she writes. “I have often asked myself how I became the woman I am. Did my mother or my hometown raise me? Maybe you cannot separate the two.”

Single Image Winners

The single image category brings together 30 works spanning five continents. Several feature couples, others whole families. A girl stands before the remains of a tea shop in northeast India, ruined by a cyclone. A Haitian mother and her son sit for their portrait in a chapel in Santiago, Chile, where many of their compatriots emigrated in the wake of the 2010 earthquake. A man peers through the legs of a giant family dog.

Iringó Demeter’s portrait of her Romanian grandmother captures an act of defiance. Ageism prevents us from normalising elderly people’s bodies, but the woman stands in her home posing partially clothed, “confidently showing what a woman her age can look like,” says Demeter. The photo is doubly rebellious because her grandmother is “a very religious woman”, says the artist. “To pose for an image in this way is not common at all.”

At the other end of the age spectrum is Philippa James’ portrait of Lucy, a 14-year-old girl who invited James to photograph her friendship group’s world of rebellion, social awkwardness and self discovery. James says she began the project intending to uncover teens’ relationships with their mobile phones. In the end she saw more similarities with her own adolescence: “The familiar, deeply rooted, yet often hidden, patriarchal ideologies and discourses that occur around teenage girls.”

However, James adds that at the heart of her work there is also a conflict. If portraiture is about the people behind the image, then the camera itself can become both a means of access and a source of unease. “I work hard to collaborate with my subjects, but ultimately, I hold the power and that makes me feel uncomfortable,” she says. “Others keep reminding me that it’s important to not let this feeling get in the way of the work, but it’s hard. I know many others grappling with this issue too.”

Navigating all of this was a judging panel consisting of Richmond Orlando Mensah, Sunil Gupta, Simon Frederick, Mari Katayama, Karen Irvine, Virgilia Facey, Marina Reyes Franco and Hoxton Mini Press’ Martin Usborne. Usbourne says: “Whether it’s young school girls in inner-city London or an elderly woman in Transylvania in her underwear, if the portrait reveals something genuine and persuasive about the subjects then I think they can speak of similar ideas.”

Two entries feature people of colour with vitiligo, a condition caused by a lack of melanin in the skin. Jasroop, shot by Kristina Varaksina, was “miserable” as a child, the photographer says. It wasn’t until she was 18 that she started habitually leaving the house without makeup. Reuben, photographed by Sane Seven, told the artist he used to think he was making people “uncomfortable just by the way [he] looked”. The subject calls for more education about diversity in school. “Everyone is worthy of love and support,” says Seven.

©Rona Bar and Ofek Avshalom

“These experiences tether us all and create a collective hope for the future.”

Virgilia Facey – Portrait of Humanity judge

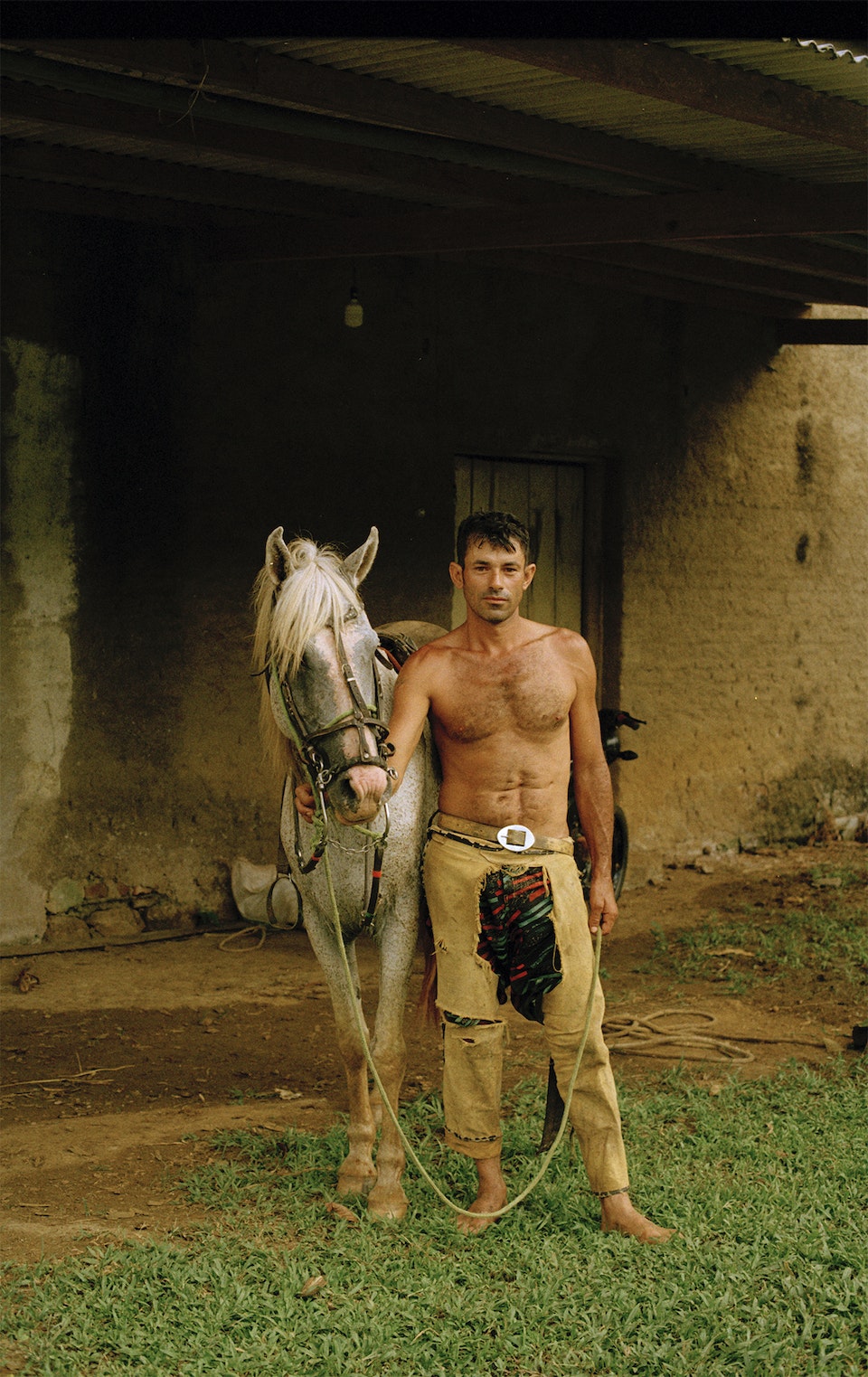

Elsewhere, Marcio Pimenta presents a Brazilian transgender woman partially hidden by a veil. Adam Docker photographs Scotto, a man who has been living in a rural Californian salvage punk community for two decades. Laurent Niles photographs the leader of the Guéré tribe of Ivory Coast, posing with a contortionist girl – both dressed for the community’s traditional dance.

And then there is Andy and Rachel. The middle-aged couple are the subjects of Tamsin Warde’s entry, which explores homelessness in Winchester. Rachel was in a vulnerable housing situation at the time, but her relationship with Andy “felt like home”, according to the photographer. Identity can become blurred by homelessness, she adds. Andy wears a shirt and tie, Rachel a sequin dress. They are both dressed up to show how much they mean to each other. After the photo they jived all afternoon to rock n’ roll. “It was such a joyful experience,” says Warde.

It is this joy, often in difficult circumstances, which perhaps best characterises the Portrait of Humanity winners as a whole. Many of the photos highlight the intractable struggles faced by people across the world, but each one captures the spirited attempts of their subjects to work through them. As judge Virgilia Facey says: “These experiences tether us all and create a collective hope for the future.”