Muay Thai enthusiast Aneesa Dawoojee wanted to challenge stereotypes about fighters. Photographing at her local gym, she discovered a mixed cast with their own stories to tell

Minutes away from the centre of Croydon – a town in the south London borough of the same name – lies the SN Combat Academy, a martial arts school run by coach Sam Nankani. Amateur and professional kickboxers from varying backgrounds gather here to train in Muay Thai. Nicknamed the ‘art of eight limbs’, the full-combat sport focuses on kicking, punching and clinching techniques to strike an opponent for points. The practice requires an unbridled commitment to its intense, discipline-led training. It is here, between the centre’s sweaty walls and boxing rings, that Aneesa Dawoojee began to create her latest series, The Fighting Spirit of South London.

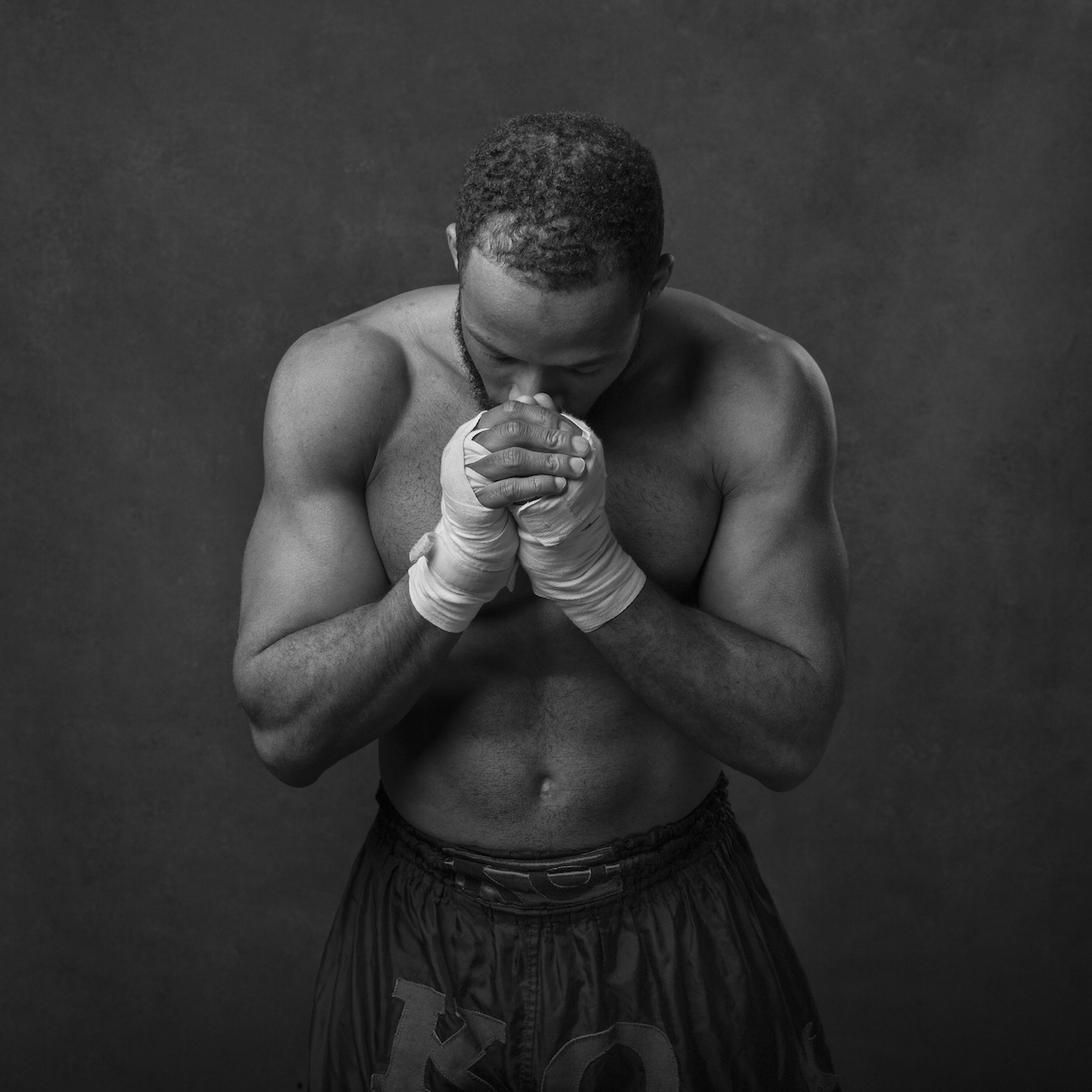

Taken over the past few years, starting in 2019 – during what Dawoojee describes as the period “pre- and post-George Floyd” – and moving on to other locations, the style of the series sits somewhere between portrait and documentary. Each velvety image offers a glimpse into the life of its subject. It mostly frames a Muay Thai fighter from the waist up in a different pose; hands in soft prayer, fingers clasping a necklace or arms loosely crossed. “I have such an interest in documentary work and that’s where the crossover is,” Dawoojee explains. “I feel that there’s a history in all of us.”

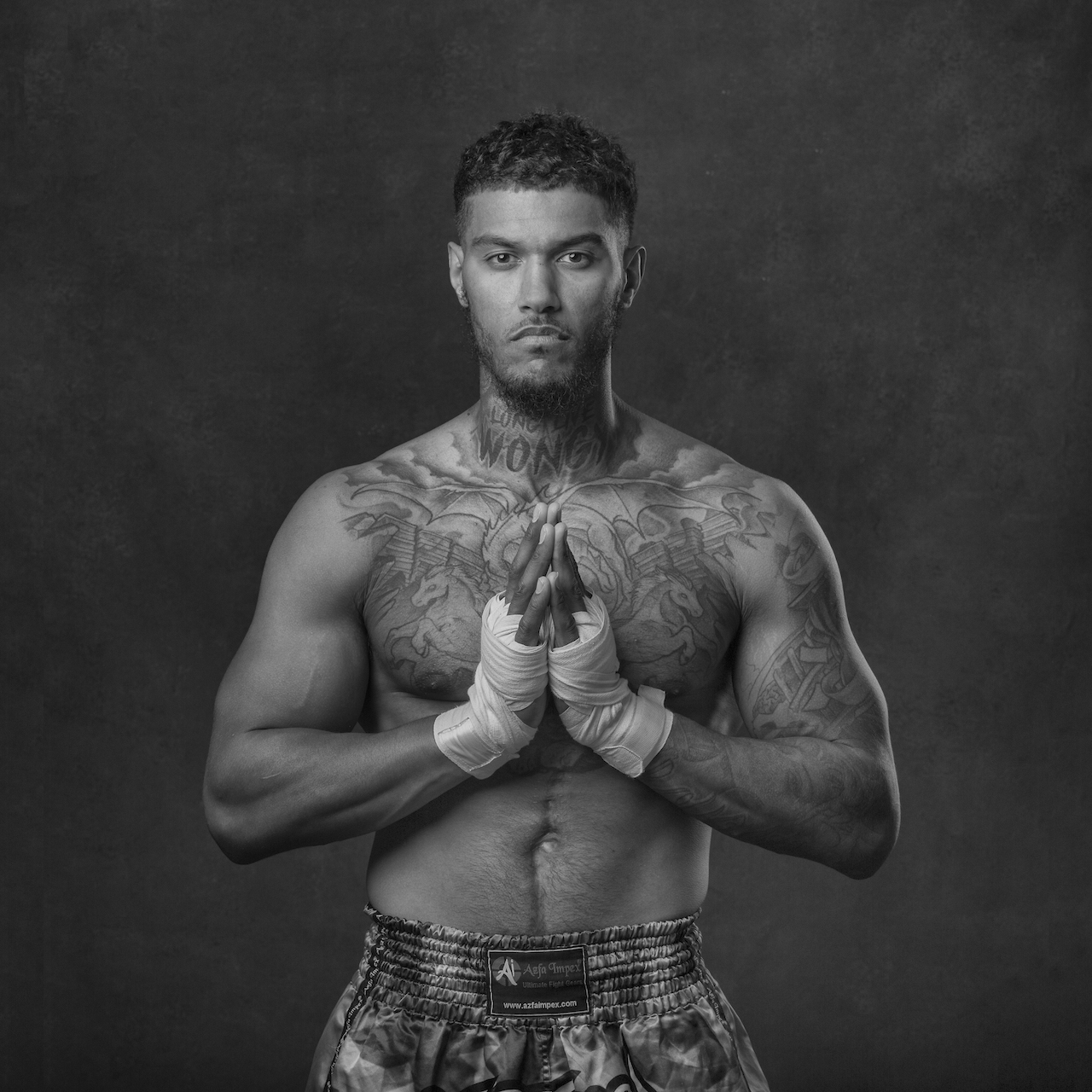

Dawoojee hopes to illustrate the many faces of the martial art, from hijab-wearing women to heavily tattooed, muscular men. The series includes 21-year-old award-winning fighter Shanelle, pictured with an uncompromising look set into her features, cradling a photo of her late best friend. South London-based personal trainer Louis [page 132] gazes into the distance in an image that pays tribute to his mother, who ran professionally for Great Britain. “Each portrait is about an individual. They can be of any race, colour, size, age, but what I’ve tried to do with this series is connect each one in some way,” says the Mauritian-Trinidadian photographer.

Dawoojee has been practising Muay Thai since her teens, and for 13 years worked with children and teenagers with mental health challenges. In the hope of finding diverse subjects for her photographic work, she began to shoot fights at the local gym centre, where her son would train. From the outset, she wanted the work to be used to educate – a social commentary on the unseen lives of Muay Thai fighters in London. Muay Thai not only preaches consistency and commitment, but also empowers and instils confidence, especially in young people. “It teaches discipline and the appropriate way of looking after and defending yourself safely, which a young child is not going to learn in the classroom,” she explains. “Equally, it’s such an empowering thing for young girls to be doing.”

It was important that these qualities were reflected in the series. “I needed to make sure that [the subjects] were the right kind of advocates if I am to use the work as an educational tool to support young people,” she explains. “The stories have to be ones that can resonate with people.” She cites Reon Wong [page 132] as an example of such an advocate. Now a professional fighter, Wong spent his teenage life unable to break a cycle of “darkness and negativity” before being introduced to Muay Thai. In his portrait, Wong stands proudly confronting the camera; a stance that highlights his confidence and commitment to the art form.

“People just assume that because they’re in the ‘fighting’ world, they’re aggressive and that they might not necessarily have much to contribute to the community. But I feel it’s the total opposite”

Dawoojee’s photographic process was a lengthy one. She spent time getting to know her subjects and each of their stories. “Building a relationship is slow and it takes time,” she says. “I need to trust them too: I’m not taking advantage of anyone’s story so there was a lot of discussion.” This slowness provided Dawoojee with the opportunity to capture the private moments, quiet determination and honest gestures of fighters. Her patient approach also echoes a question that lies at the heart of her work: how can we capture vulnerability without encroaching on a sitter’s personal boundaries?

The series is mainly shot in black-and-white: an attempt to represent the individuals in the simplest way possible. Every sitter was asked whether they would feel comfortable wearing a T-shirt or having their skin exposed. “I believe the human body will tell you so much more than the face; the body tells you a thousand things,” she says. “Going from black to white means the focus is on their humanity.” This is also the reason why the series is photographed in the style of traditional portraiture in the locker room, away from the bustle of the fighting ring to achieve that “quietness”. “The storytelling part is private – you can’t have an audience listening in,” she explains.

“I believe the human body will tell you so much more than the face; the body tells you a thousand things. Going from black to white means the focus is on their humanity”

The Fighting Spirit of South London serves as an antidote to the traditional ‘fighter’ stereotype, which Dawoojee believes is often reduced to caricatures in Western media. Instead, it offers a more accurate portrayal of the “small voices” within the sport. “People just assume that because they’re in the ‘fighting’ world, they’re aggressive and that they might not necessarily have much to contribute to the community,” Dawoojee explains over a video call from her home in south London. “But I feel it’s the total opposite.”

The resulting images are profound in their intimacy and invite intense speculation. Perhaps one of the most arresting is The Humble Warrior [page 136], a fighter ready for combat but happy to remain seated and resolute in his own body. Also featured is Grenfell firefighter Ricky Nuttall [page 135], a defiant portrayal that captures the emotional grey zone between resilience and defeat. Dawoojee’s search for authenticity allows her to showcase the breadth of Muay Thai fighting life. With a chronicler’s eye, she captures the many facets of this little-explored community and sheds light on the complex emotions that come with taking part in the discipline.