Today, 28-year-old Addy is one of the most in demand photographers working in the UK. He has shot covers for the likes of Harper’s Bazaar, Time, Dazed and Rolling Stone, and photographed cultural icons such as FKA Twigs, Kendall Jenner, Tyler the Creator, and Naomi Campbell. He is also the founder of Nii Journal and Nii Agency – a biannual culture magazine and a modelling agency respectively.

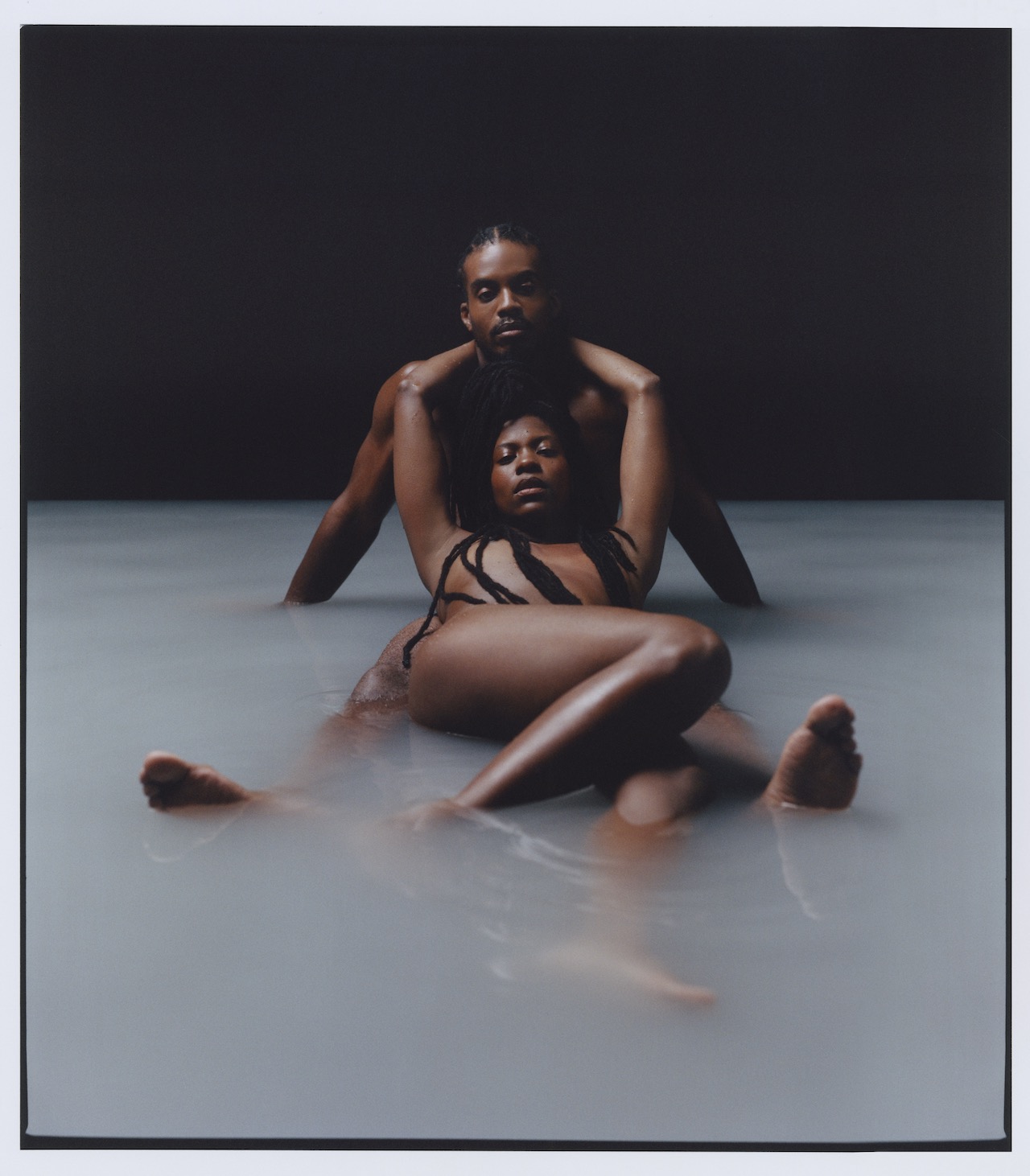

Addy’s debut monograph, Feeling Seen, is a compilation of both commissioned and personal projects. “From age 16 to 28, the common denominator has been the desire to be seen. When I was unknown, I just wanted visibility,” he says.

The book includes a foreword from British Vogue editor-in-chief Edward Enninful, as well as an interview with curator Ekow Eshun that delves into Addy’s philosophy as an artist. Interspersed between Addy’s striking images are quotes from friends in the industry, including fellow photographer Nadine Ijewere, and stylist and editor Gabriella Karefa-Johnson. They too reflect on the first time they “felt seen” in the industry.

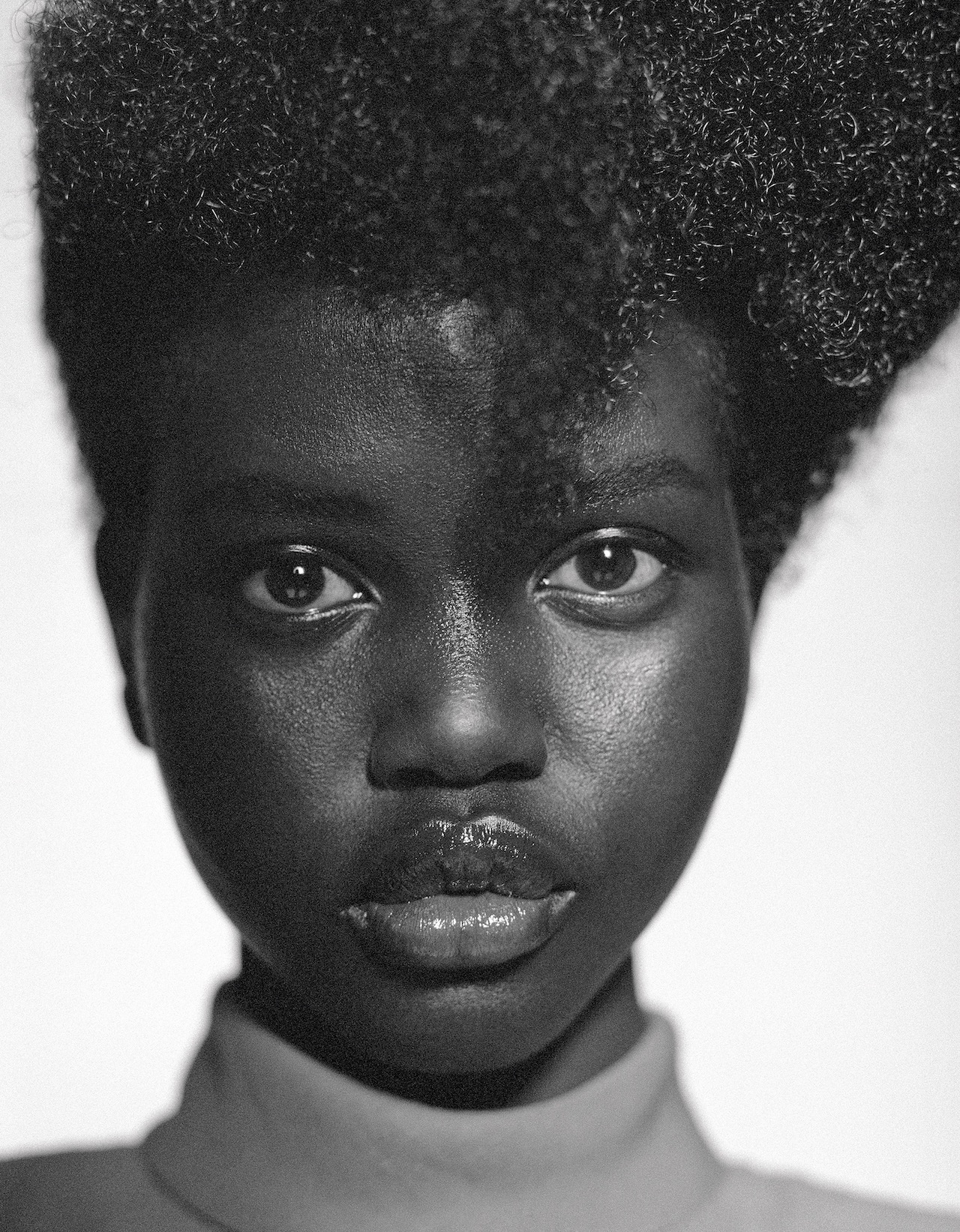

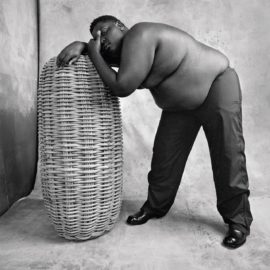

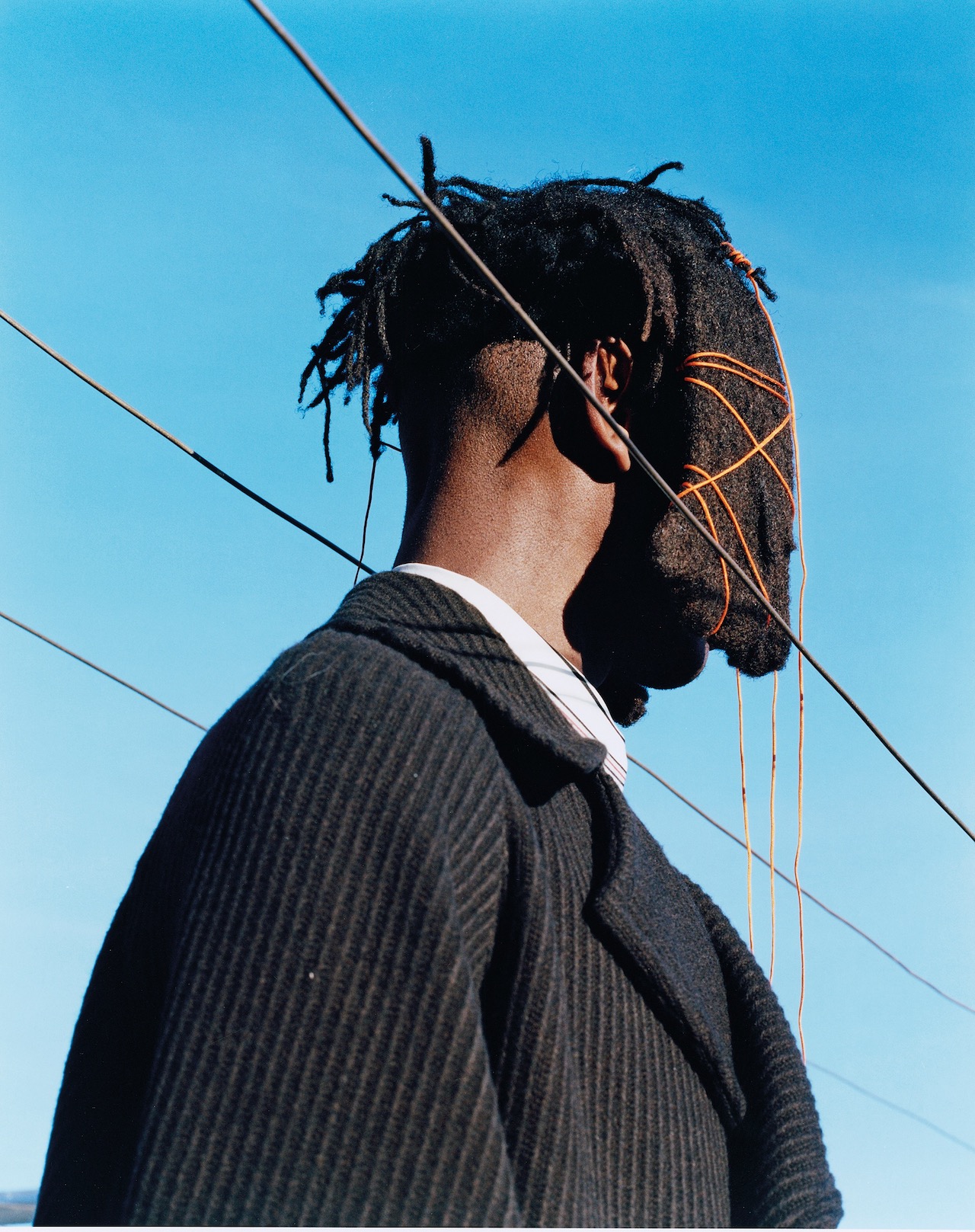

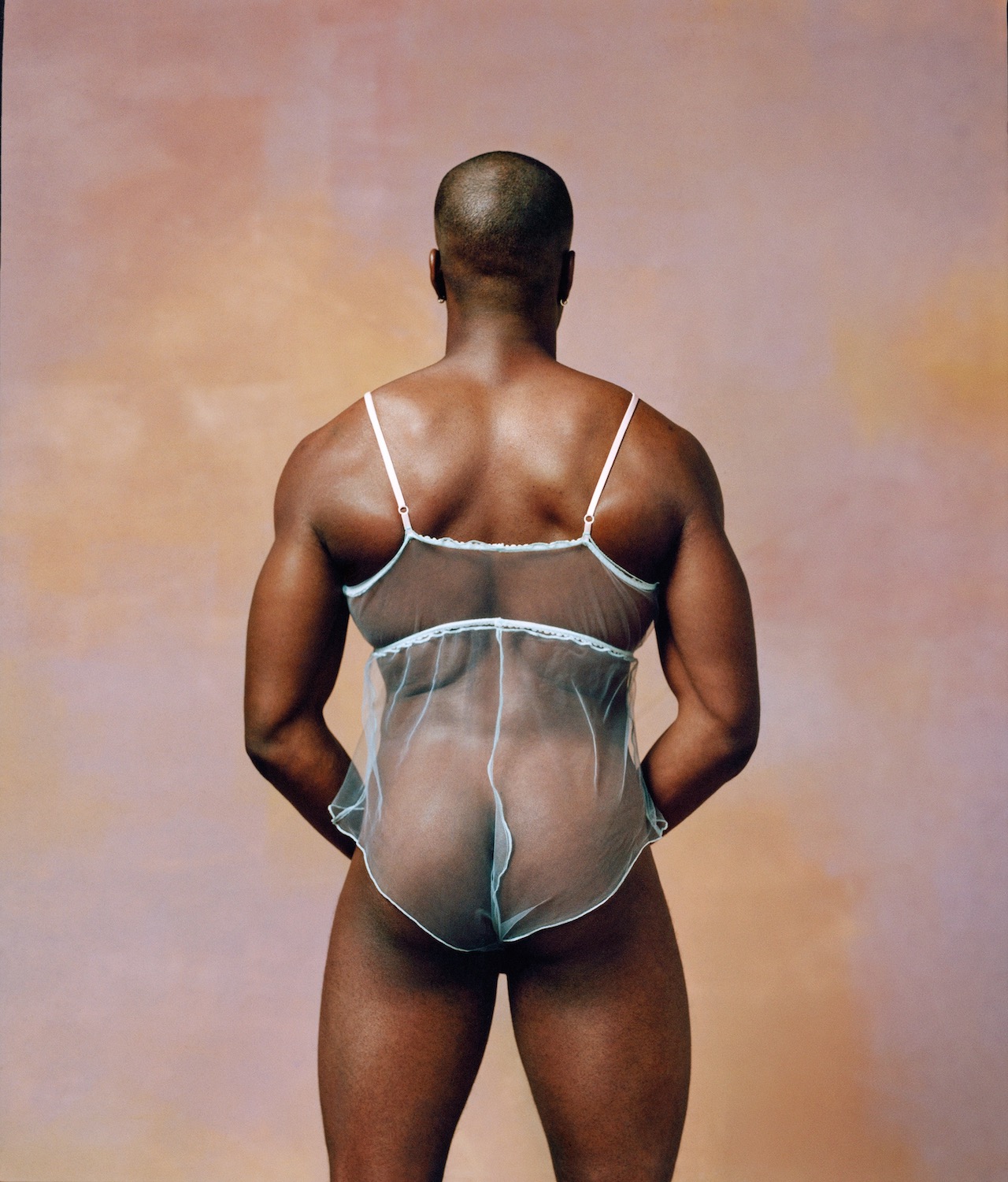

Charting his visual journey so far, Feeling Seen exemplifies a career dedicated to promoting Black visibility, beauty and creativity. Addy works exclusively in analogue. “I love the printed matter… Digital is very important, but for me, I make work to be physically printed,” he says. “In school, I was known among my friends for always reaching past the gallery rope to try and touch the paintings.” This affection for texture translates into images that depict a tangible, real Black existence. Skin, hair and fabric flow, creating an atmosphere that is recognisably Black, safe and warm.

The photographer has also “dabbled” in various studio roles, from makeup to hair, all to further understand the craft of photography. “I need to be able to communicate in their industry’s language so that we can all work on the same page,” he says. Addy is committed to celebrating Black talent wherever he finds it, applying his attention to detail in all elements. “Respecting and understanding the different roles creates trust, and once you have trust, the work just flows,” he adds. “I always try to create a chilled, collaborative environment. A safe space.”