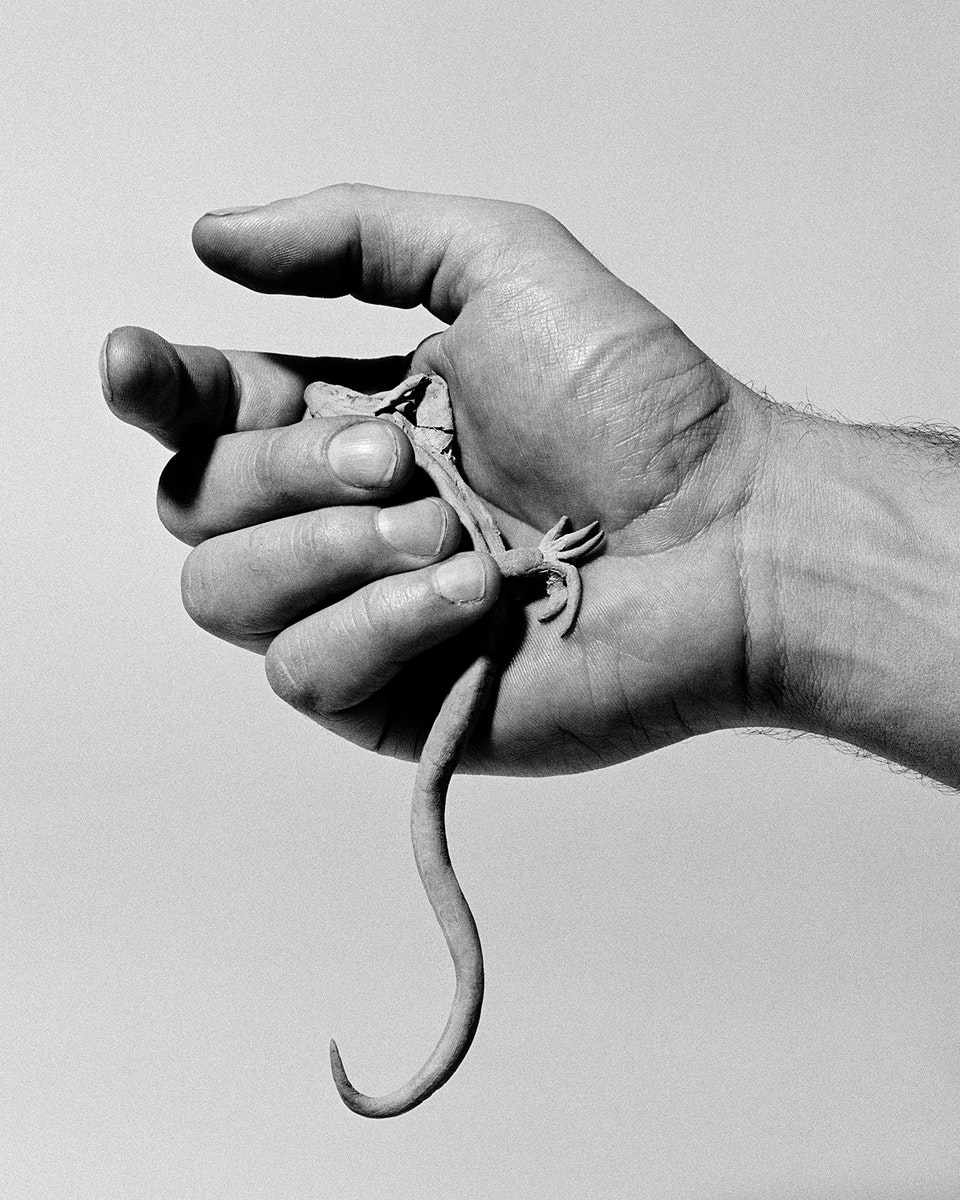

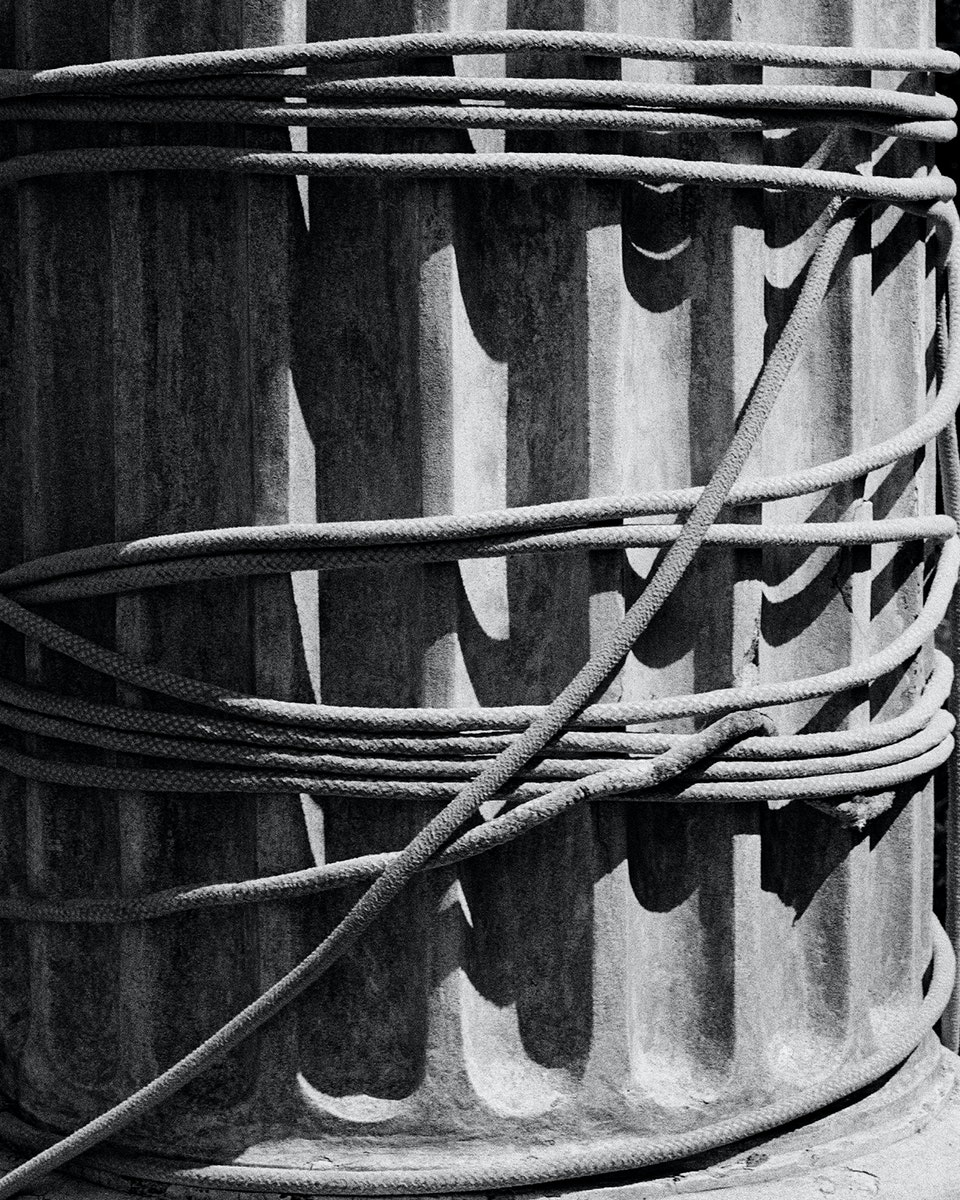

Photo: © Giulia Parlato.

Joint runner-up for the BJP International Photography Award 2020, Giulia Parlato creates a forged archive of historical artefacts to question our understanding of the past

BJP International Photography Award 2021 is now open, recognising contemporary talent of the highest calibre. Enter now.

Can we ever truly know what happened in the past? It’s a question at the heart of Giulia Parlato’s Diachronicles, in which the Italian photographer appropriates the visual language of historiography to highlight its fragility in pertaining to fact. “History was written, for the most part, by people who won wars,” says Parlato. “This means we have a very narrow view on what’s actually taken place.”

Principally, Diachronicles is influenced by modern archeological studies, forensic crime scene photography and the museum space — imagery and practices that attempt to ‘reconstruct’ the past from scattered clues. The work appears to present an archive of historical artefacts, sites and dioramas. In reality, it’s all artificially staged in London-based studios and on location in Sicily, or taken from museum forgery collections. The project is a fiction: “a forgery in itself.”

The idea for Diachronicles was conceived when Parlato visited The Warburg Institute in London. Here, she browsed the photographic archive of counterfeit works that had been sold to cultural institutions around the world: once such instances of fraud had been discovered, and each artefact’s value instantly diminished, the objects were promptly stored away from public view. It begs the question, how can something hold a deep historical significance at one time, and then lose it entirely a moment later? How can ‘truth’ be subject to change?

With this in mind, Diachronicles seeks to expose the limitations inherent to second-hand accounts of history. In the series, gloved hands unearth, containers transport, and utensils measure. Accordingly, viewers are implored to search for meaning: a reflection of the human pursuit of knowledge, and the arbitrary value we assign to inanimate objects; the neat and linear narratives we construct from obscure fragments. Diachronicles’ reality, however, is much more frustrating.

“Ultimately, it’s impossible to tell a finalised account of the past,” says Parlato. “Every image is constructed in a way that makes you look for factual information. In the end, you’re left without any. The facts are missing.”