This article was published in issue #7892 of British Journal of Photography. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.

What part do museums play in shaping our understanding of history? It’s a question that London-based Italian photographer Giulia Parlato has asked herself often in the past few years. “They’re places to learn about the past, and places where objects end up being elevated to a higher status of interpretation. But what happens to the discarded, unrecognised, or lost material culture that is not displayed?” she says. “A museum is tidy, organised and clear. We like to think about time as a linear, horizontal path, but there isn’t such a thing. It’s much more complicated than that.”

Parlato’s new project, Diachronicles, emerged from this thinking, and she started working on it while researching for another work at The Warburg Institute in London. “While I was there I began browsing through the forgery section, and I started to think about the relationship that history has with fiction. In particular, what happens when you disrupt the historical narrative, which is ultimately really fragile, being a fabricated story in itself,” she says.

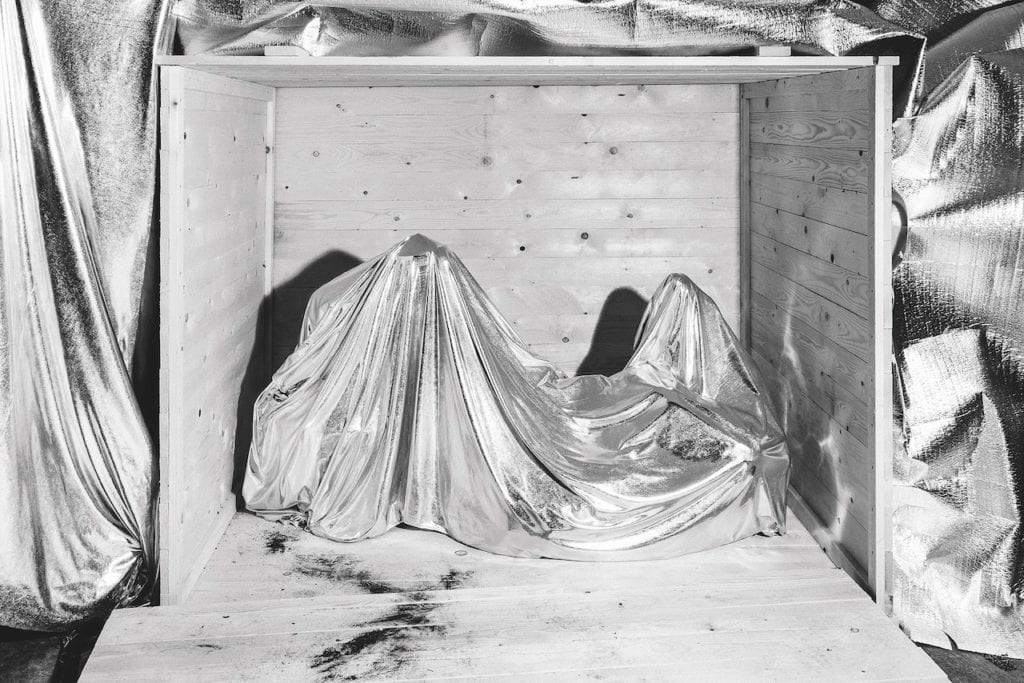

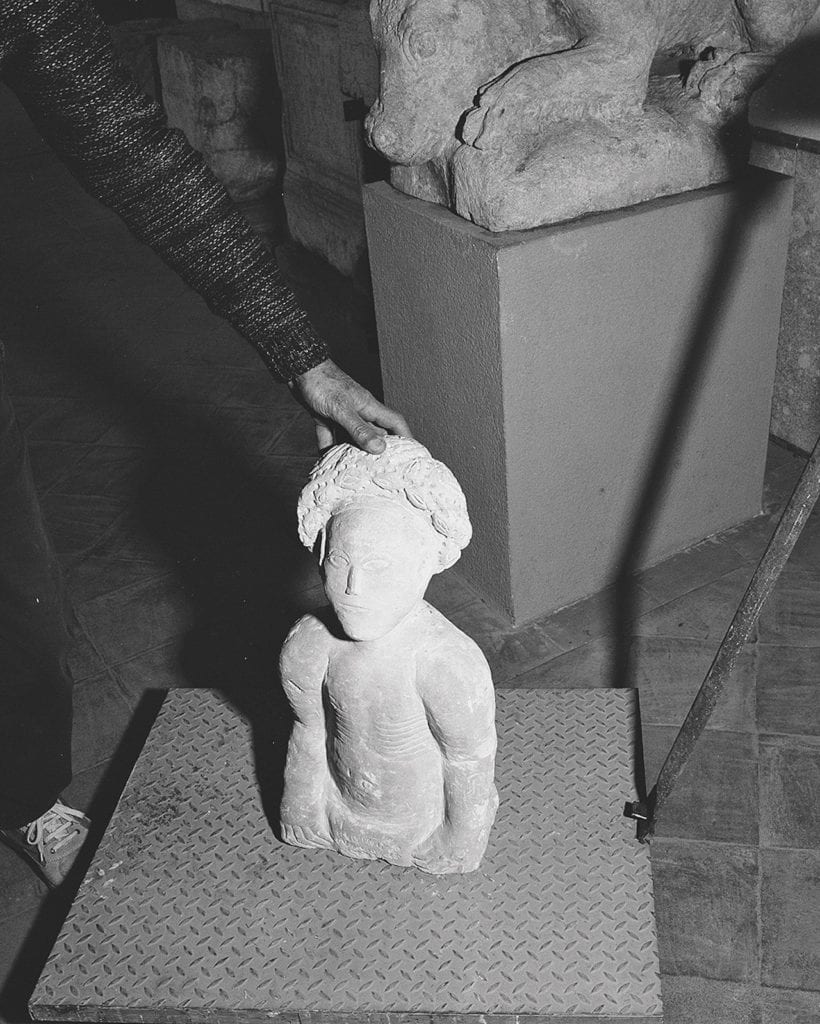

As she began shooting, Parlato got in touch with curators at the Regional Archaeological Museum Salinas in Palermo and learned of the story of Dr Savario Cavallari and Gaetano Moschella, an archaeologist and a farmer respectively, who in the mid 1800s produced and sold a series of limestone figures to museums across Europe as Ancient Greek artefacts. Captivated, she began to think of how she could create her own historical fictions in front of the lens. Diachronicles thus features photographs that appear to be presenting an array of artefacts and dioramas when, in fact, none of what we see is what it seems. “It’s all either created by me or friends, uncategorised material, or a forgery taken out from a museum storage space,” she explains.

The images were staged in studios in London, on location in Sicily, in museums and in the photographer’s garden, knocked together from objects and set-ups that might just pass as ‘authentic’. Shooting in black-and-white, Parlato wanted the images to have the feel of those from a timeless archival collection, hoping it would lead the viewer

to scour them for evidence. Each of the photographs is titled so as to destabilise the authenticity of what we’re seeing – an image of a museum display cabinet, for instance, is called The Storyteller, “because it’s a condensed space where narratives take place, like the pages of a book”.

Parlato has plans to expand the work over time. She will be accompanying an archaeological expedition in Turkey in the summer, and is researching the advanced technologies that museums use to authenticate artefacts. “Even though inaccuracies, scams and fake news have always existed,” she says, “I think that particularly interesting questions can emerge from a body of work about the fragility of historiography right now.”

—