In a new book, A Voice Above the Linn, Lawrence tells the story of Jim Taggart and his sprawling gardens, nestled amid a remote valley on the western coast of Scotland

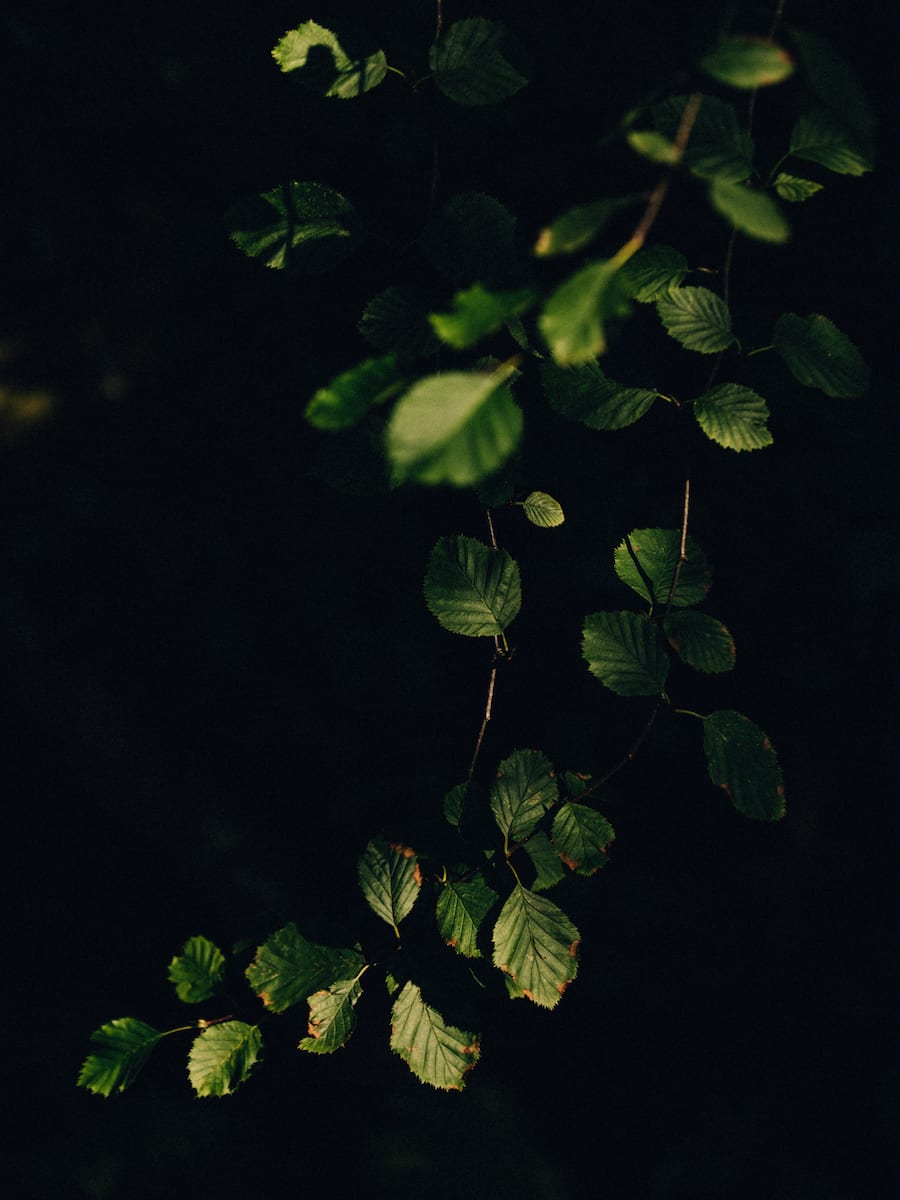

A heavy haze coats the vast mountains of western Scotland. The deep waters of Loch Long and Gare Loch spread out beneath them. The sky is clear, and the air is light; stillness and silence prevail. And then, hidden on the far southwest edge of the Rosneath peninsula, an ecological miracle emerges. Tangles of plants punctuated by lofty trees extend their canopies outwards over vast expanses of greenery studded with brilliant flowers; a contemporary Arcadia; a lost wilderness; a green jewel; a place where nature runs wild; this is Linn Botanic Gardens.

A narrow rock valley shelters the botanic gardens, and the swift North Atlantic Current warms them. The combination is magical, creating a subtropical microclimate, which allows for almost 4000 plant species – many endangered and drawn from across the globe – to flourish, undisturbed. Species from China, Peru, and the Himalayas; ferns, bamboo, magnolias, rhododendrons, and several champion trees. As Dr Ian Edwards, of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, described it, “Linn is the most biodiverse place in Scotland”. And, amid the three acres of verdant vegetation, which creeps across steep rocky terrain and a network of paths, sits a Victorian villa: majestic with its gabled roofs and stone walls consumed by climbing plants. Built in 1860, Linn villa existed before the botanic gardens that now surround it: a rambling plan of winding wooden staircases; high-ceilinged, light-flooded rooms; narrow corridors and ornate stained glass.

“When we arrived, it was a peaceful day,” remembers Robbie Lawrence, who first travelled to the gardens, with the illustrator Emma Tudor-Bloch, in 2016. “Low-hanging mist over the loch; late winter, early spring; this beautiful west light. The place just felt magical. It is incredibly dense: a cliffside full of shrubs and trees. And, as you make your way through the garden, you discover a huge dilapidated house, which is astounding when you first see it. And then there was Jim,” continues Lawrence, describing his first encounter with Dr Jim Taggart, owner of the gardens.

In his younger years, Taggart, an arresting octogenarian with a furrowed face framed by tangled grey hair when Lawrence met him, studied botany in Glasgow before reading theology at Oxford, after which he entertained becoming a priest. Instead, in 1971, he purchased Linn villa and embarked upon transforming its steep and rocky gardens. Taggart already possessed an extensive plant collection, and he worked hard reorganising the space to accommodate it. He cut down trees and hedges to allow for more light; removed decades’ worth of debris from the Meikle Burn gully, expanding plantings down the garden’s steep banks; and built water features to prevent flooding. He also grew his collection, sourcing exotic species from all over the world. In 1999 the Linn was officially named a botanic garden given its array of plants, many endangered, and Taggart’s son, Jamie, committed to cataloguing the collection.

At their pinnacle, the gardens housed over 8000 taxa carefully arranged around a winding one-kilometre long path. Walking up towards the Linn through the glen, steep slopes ooze flowering rhododendrons, exotic climbers and the delicate, spider-like buds of Chinese Epimedium; a towering Schefflera fengii tree from southwestern China looks on. Above the glen, in the northeast corner, sits a bamboo garden that once contained 40 varieties of the plant. Meanwhile, an exotic wood – with a delicate Australian snowdrop tree and ornamental Japanese Katsura – occupies the northwest side. Nearer the house lies a New Zealand alpine lawn and a spiky bed of cabbage palms, yuccas and grasses, giving way to a lily pond and rockery below. Water is present throughout. Flowing from a waterfall at the garden’s peak, the Meikle Burn cuts through the land; several man-made ponds and a fountain also feature.

Having first heard about the gardens from his sister, it was four years before Lawrence visited them. But, when he finally did, he knew he had discovered something special. “Without even introducing himself, Jim began telling us about the gardens and took us around them,” remembers Lawrence. However, a tragic story soon emerged. His son Jamie, a part-time firefighter and botanist, who took over the gardens in 1999, had travelled extensively, researching and sourcing new species for the grounds. In 2013, on one such trip to a northern, mountainous region of Vietnam, Jamie disappeared. He remained missing for several years until his body was discovered at the bottom of one of the mountain’s higher passes. “Jim lived in a perpetual state of mourning for his son,” Lawrence continues, “and the garden became an emblem for Jamie, who had been part of designing and developing it.” Small tributes sit throughout: a portrait above the fireplace; wild greenhouse experiments, which Jamie started; a pile of rocks alongside the waterfall.

The tragedy was significant. However, it is not the focus of Lawrence’s work. Instead, the intense relationship between nature and man, which he observed at the Linn, compelled him, and he watched and photographed Taggart amid the rich surroundings he had given his life to cultivating. Here was a man at one with nature; devoted to a garden he had built and nurtured. “He lived for the garden,” says Lawrence, “it energised him. When he was in it he was far more lively and lucid than when he was inside; it was therapeutic.” The images bear witness to this connection. With his wild beard and brooding face, carved with age, Jim blends into his surroundings; an ancient tree among those spread across the property.

Over the next four years, Lawrence returned to the Linn along with Tudor-Bloch whenever he was in Scotland. He captured the garden and its owner through the seasons, gradually building an evocative portrait of the place. The visits were much the same: Lawrence and Tudor-Bloch accompanied Jim while he wandered the garden, and then they would move inside for tea. “He would tell us stories about his life,” remembers Lawrence, “swinging from decade to decade.” Lawrence’s photographs capture the vast vistas, heavy with mist. They hone in on more intimate details too: beads of water pepper an overturned leaf; a brilliant-red flower bud glows. Images of the house’s interior also feature, as do delicate arrangements of twigs and leaves, positioned by Tudor-Bloch and given to her by Jim. The photographs are “anthropomorphic”: “Every image is a portrait of Jim. It could be a flowerbed of snowdrops or a pile of books, it’s how you represent someone through different things.”

Lawrence had always planned to make a book of the project, however, it wasn’t scheduled for this year. The pandemic changed that, and A Voice Above the Linn, published by Stanley/Barker, collates images he made during his many visits: a record of the gardens and their owner. Many of the photographs were shot during Lawrence’s first visit, which resonated with him profoundly. And several of the later stills were taken on his last trip, when he discovered that Jim had died. “I didn’t know because we wouldn’t plan our visits; he didn’t have a mobile phone or anything,” says Lawrence. “So we just wandered in, and I was snapping as usual, but then realised something felt strange; the garden was completely overgrown.” Jim was gone; it was summer, and a warm light bathed the grounds and the mountains beyond them.

Lawrence spent the first UK lockdown collating the material he had of the gardens into an edit for the book. The result is a moving record of Taggart’s later years and the Linn Botanic Gardens, which he devoted to them. Physically, the publication is resonant of a garden journal: “I wanted it to be like one of the journals he kept in his shed, gathering dust; I wanted it to be accessible, not too highbrow.” And four poems, written by the esteemed poet John Burnside, segment it. A short film, of the gardens and the surrounding area, shot by Lawrence following Jim’s death accompanies the work, with Burnside reading excerpts of his poems over it. These respond to the images through poignant prose, and together, image, text and film evoke the atmosphere of the gardens. transporting readers to a magical place, the existence of which is now unclear as ownership of it moves into new hands.

A Voice Above the Linn is available via Stanley/Barker; a portion of the book’s sales will go towards The Friends of The Linn charity, which supports the upkeep of the garden. Lawrence has also released a limited edition of prints from the series here.