Each year, British Journal of Photography presents its Ones To Watch – a group of emerging image-makers, chosen from hundreds of nominations by international experts. Collectively, they provide a window into where photography is heading, in the eyes of the curators, editors, agents, festival producers and photographers we invited to nominate. Throughout September, BJP-online is sharing their profiles, originally published in issue #7898 of the magazine.

“Certain places seem to exist mainly because someone has written about them,” writes Joan Didion in Sojourns – one of the chapters in her 1979 book of essays, The White Album. “A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest,” she continues, “remembers it obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his image.”

The passage reflects Neha Hirve’s practice, which she references to her work – work, which spans far-flung places, but also those closer to home. “With all my subjects, I am trying to create a story around the place. I am trying to turn the place into a metaphor.”

Every place that populates her work feels allegorical: Hirve tells the story, but it also represents something more – it makes a point, it asks a question, it symbolises something else. Wild hunt follows the storm chasers of Tornado Alley, US. But it also invites us to consider what compels them to hunt vast funnels of wind swirling across middle-America. Her project Full shade/half sun documents Auroville: a utopian-city built-in 1968 on barren land, near Pondicherry City, India. Hirve photographs the bizarre landscapes, but in doing so considers how they perpetuate the myths surrounding the city and the inhabitants who it houses.

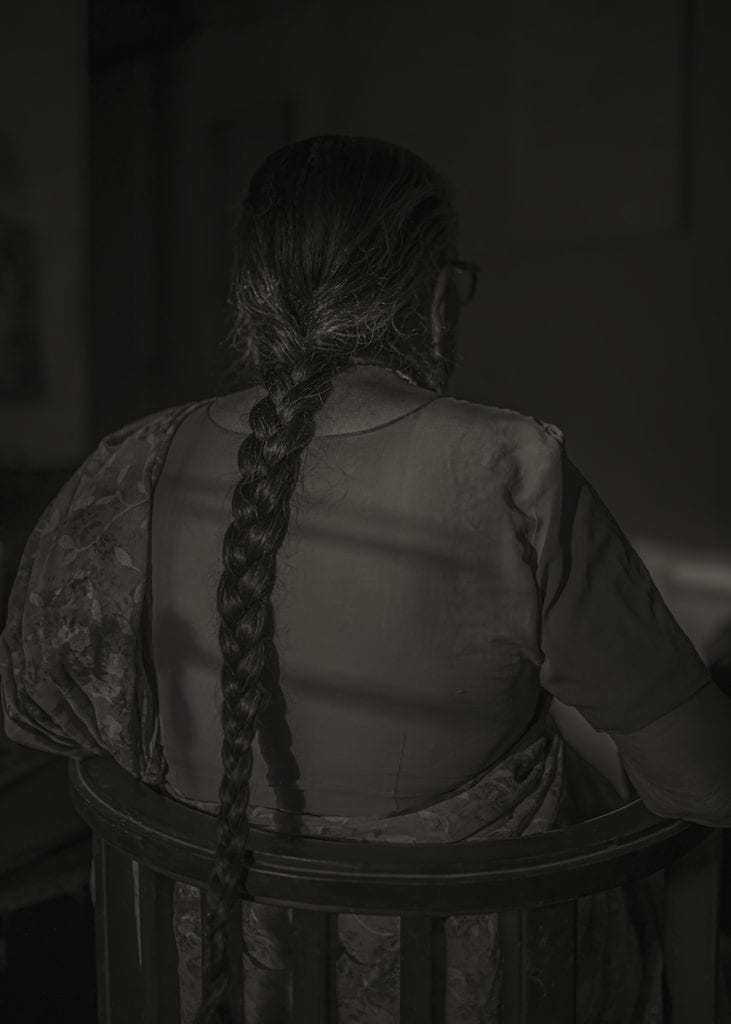

The subjects of Hirve’s work are real, yet they feel otherworldly – an effect engendered by the blend of documentary and magical realism, which she combines to make work. “Little moments and narratives, which offer a window into something mysterious or fantastical compel me,” she says. In a light that is leaving, for instance, which depicts a group of eco-activists in Hambach Forest, a golden glow elevates the forest and its protectors to another realm. Among ancient woodland, ravaged by nearby mines, a mysterious and desolate world emerges. And, in both your memories are birds, Hirve conjures a magical space from the confines of her grandparents’ home in Pune, India, during lockdown: birds glide and the sky deepens from blue to a dusky purple. Despite the unease from which it was born, a lightness runs through the work, life and moments of colour amid the vacuousness of isolation.

Hirve’s entry into photography was slow and reflective. She received her grandfather’s old camera aged 11, yet it was only a decade later that she developed that first roll of film. Hirve initially studied film, but not long after turned her focus to photography and began to experiment with simple reportage during her MA in Photojournalism at Mittuniversitetet, Sweden.

“Little moments and narratives, which offer a window into something mysterious or fantastical compel me”

“Neha Hirve invites us into worlds where we can balance between being spectators and participants,” says the independent editor, curator and artist Rebecca Simons. “Her documentary-based work goes beyond the presentation of situations and facts, allowing us to engage in off-moments with her and the communities she represents. Hirve communicates through still and moving images, metaphors and myths. Intriguing tension and mystery prevail in the work. Through them, we can enter a time capsule, a vacuum, or sometimes, literally, the silence before the storm. It is an excellent example of contemporary documentary photography, which succeeds in turning us into active viewers instead of passive consumers.”

During an artist residency in Riga last October, Hirve frequented a forest just outside the city with myriad mystical associations. “I started experimenting with Kirlian photography,” she says, “which allows you to photograph the auras of living things.” Kirlian photography reveals the conjectural energy field or aura surrounding an object, but the meaning of that aura is contested. Scientists attribute aura-variations to water and voltage, while aficionados believe they reflect the physical and emotional states of the object in question. The experiment sparked the beginning of a new project: to explore photography’s dual role in providing pseudo-scientific evidence of something while also amplifying the fiction surrounding it.

Hirve explores the present, but also draws heavily on the past, delving into archives for many of her projects: “I pull photographs from the archives of a place to see how the narrative has evolved over history,” she explains. This method is characteristic of a photographer who favours a slow and considered approach over the impulsive. Hirve has also never been able to pursue photography full-time. “It is liberating in a lot of ways – I work slower, I can go at my own pace, I can take my time-researching projects.” The result is something deeply considered: beautiful and challenging at once.

This article was originally published in Issue #7898 of British Journal of Photography: The Talent Issue.