David Goldblatt: Seven decades of Johannesburg

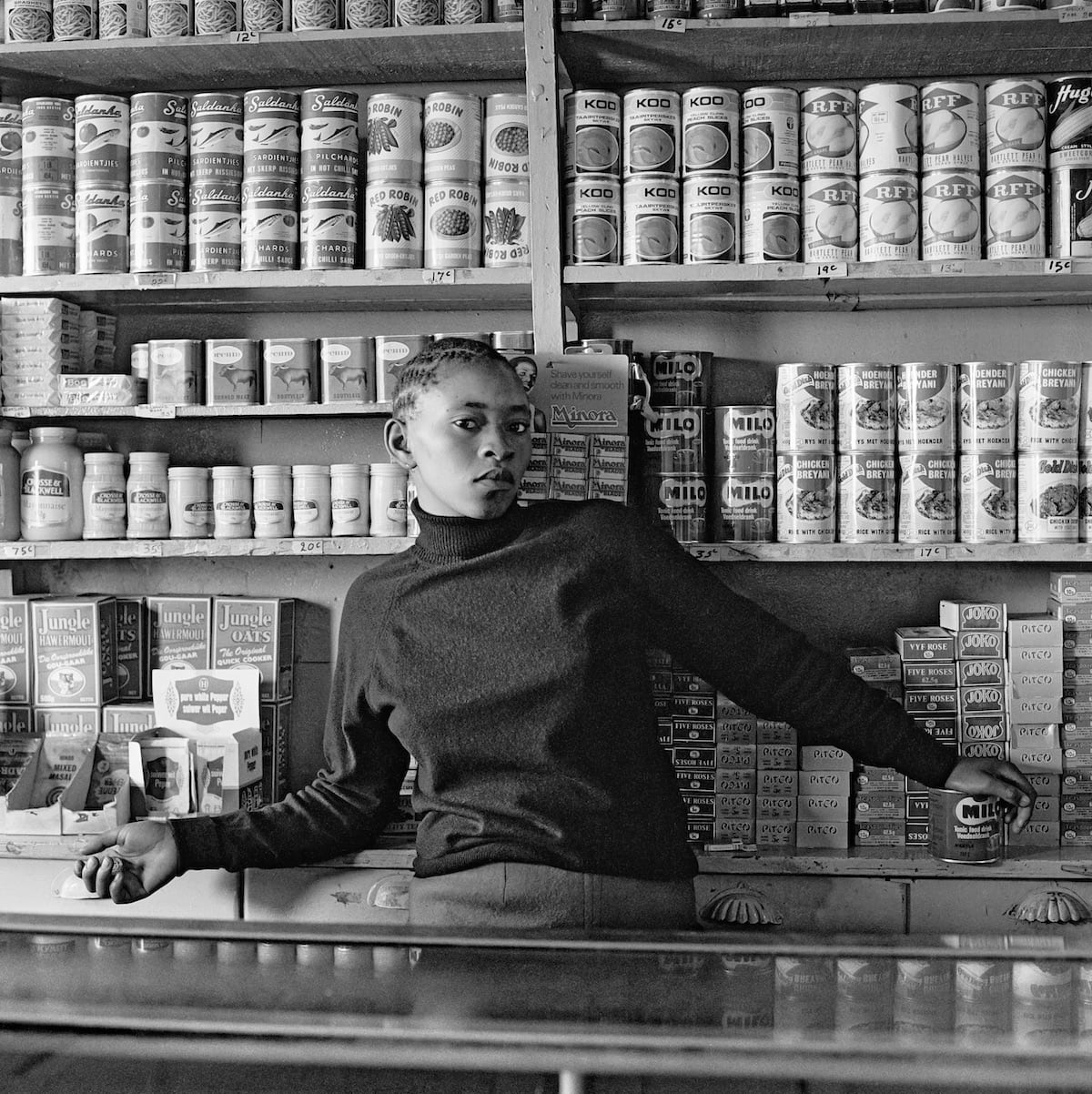

Shop assistant. Orlando West. 1972 © David Goldblatt, courtesy Goodman Gallery.

Source: Soweto

Young men with dompas (identity documents that every African had to carry), White City, Jabavu, Soweto, Johannesburg, November 1972 © David Goldblatt, courtesy David Goldblatt and Goodman Gallery Johannesburg and Cape Town. Shown in the exhibition David Goldblatt at Centre Pompidou, 21 February-13 May 2018

Source:Pedestrian Railway Bridge, Leeu Gamka, Western Cape, 30 August 2016 Pedestrian bridge over the Cape Town-Johannesburg railway line built as prescribed under the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act n° 49 of 1953. The notices separating two racial streams were removed in about 1992, but the bridge, serving a population of about 1500 people, remains © David Goldblatt, courtesy David Goldblatt and Goodman Gallery Johannesburg and Cape Town. Shown in the exhibition David Goldblatt at Centre Pompidou, 21 February-13 May 2018

Source:© 2022 - 1854 MEDIA LTD