In 2015, after two years of documenting the Ukranian Revolution, “I just wanted emptiness and silence,” says Maxim Dondyuk. “I decided to concentrate on a project where there wouldn’t be any people.”

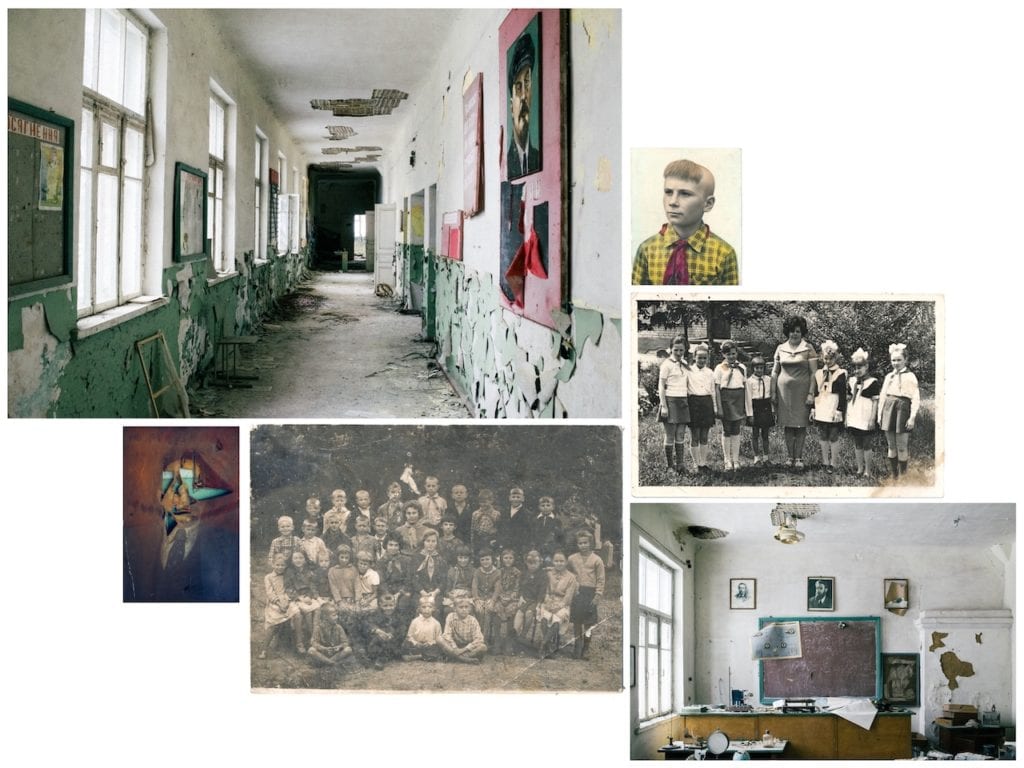

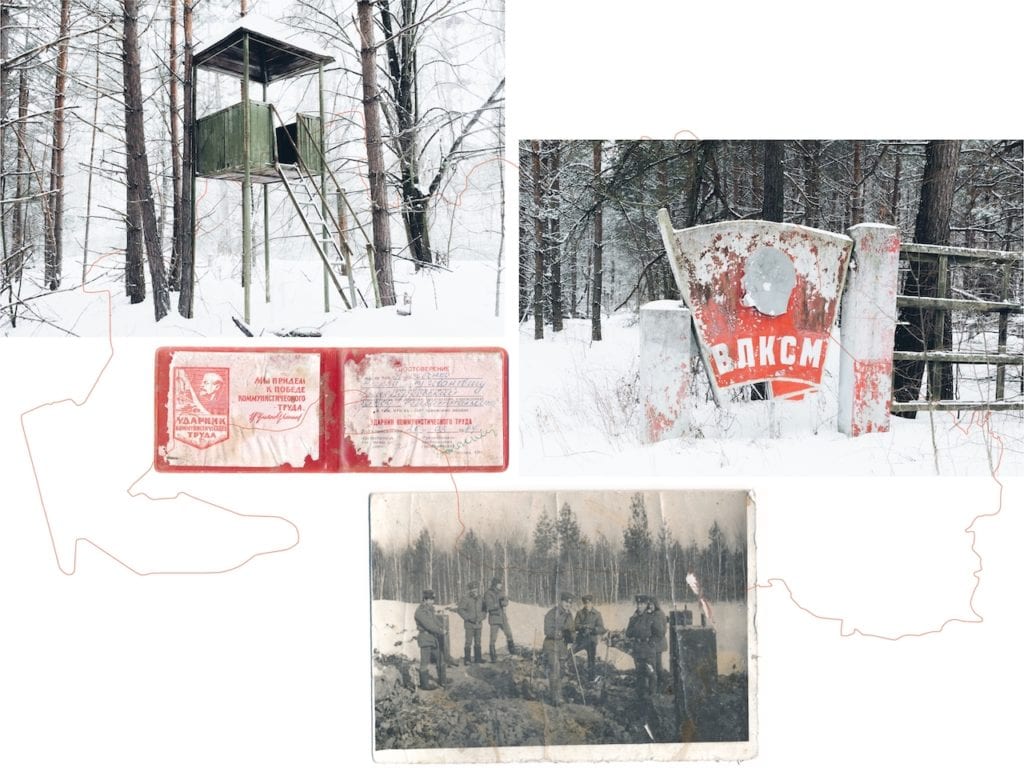

The photographer had visited Pripyat, the Ukranian “ghost city” ravaged by Chernobyl’s nuclear disaster of 1986, as a photojournalist ten years prior, but in 2016, he decided to return to photograph the landscape as a representation of a bygone era. Accompanied by a guide, Dondyuk embarked on long winter walks through the exclusion zone, photographing derelict structures engulfed in moss and nettles, left abandoned within the woodlands of the region’s vast snowy landscapes.

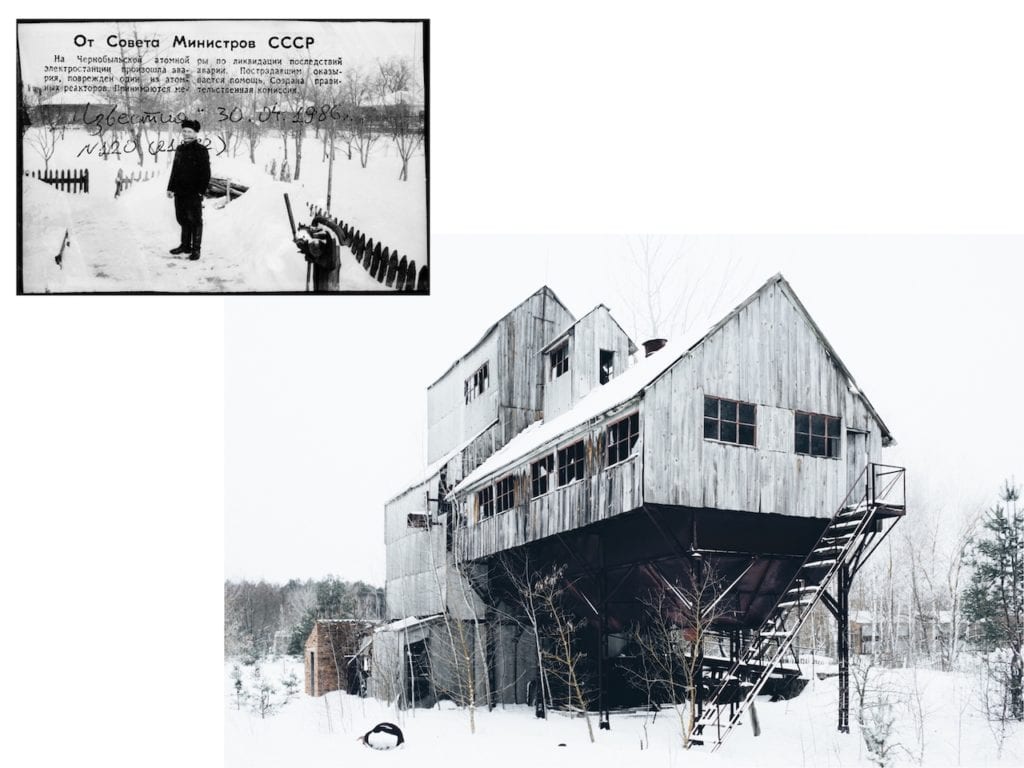

Wandering through one of the thousands of evacuated homes, the photographer discovered piles of postcards, letters, and photographs, hidden beneath 30 years of debris. The Ukranian government considers anything left behind as “radioactive trash”, and forbids visitors from removing them from the exclusion zone. But, Dondyuk couldn’t bear to leave the artefacts he found to decay, so over the next two years, he continued to return, disguising himself as a landscape photographer, smuggling the photographs out of the exclusion zone, and rebuilding the lost archives of the families and individuals who once called the region their home.

Now, the images, films, letters, maps and articles are presented in a virtual gallery, alongside Dondyuk’s own documentation of the landscape as it is now. Here, the photographer shares his story, the process, and future intentions for the project.

How did this project come together, from when you first visited Chernobyl, to the production of this virtual gallery?

After the Ukrainian Revolution of 2013-2014, a year of war in Eastern Ukraine, I just wanted emptiness and silence, so I decided to concentrate on a project where there wouldn’t be any people. At the beginning of 2016, I went to the Chernobyl exclusion zone, where I started visual contemplation and exploration of the abandoned territory.

At the time, I had no clue how everything would turn out, and what this project would become. During my first visit, I went into a partly-destroyed house, and I noticed several postcards and letters laying on the floor. I studied them carefully, and left everything where it was. But, the thought of how people had left behind such priceless memories, and why Ukrainian institutions didn’t bother to collect these visual artifacts, stuck with me.

Having no idea what was waiting for me and on what scale, I dedicated the following two years to the exploration of abandoned houses in Chernobyl, where I searched for visual artifacts of the past — old films, photographs, letters, and postcards. After that it took me several months to restore and scan everything that was found, and around a year to put it together into the website.

Was it difficult to gain access to this material?

Ukrainian authorities do not allow people to take anything away from the exclusion zone, because they perceive it as radioactive trash, but I couldn’t watch a huge part of history disappear.

No-one can enter the Chernobyl exclusion zone without prior approval from authorities, and a guide to accompany you everywhere. In the two years I visited Chernobyl, I pretended to be a landscape photographer, and sometimes my friend Dima, who was assisting me, distracted our guide so I could collect the photographs and hide them in my camera bag. We had to hide everything within our car as we passed through the checkpoint to leave. I wasn’t afraid to be arrested or fined — I was more afraid they would burn everything like trash.

Eventually I became tired of working as a smuggler, of the anxiety each time my car was checked, and the project was becoming difficult financially. In 2018, I decided to publish my work in The New York Times to draw attention to my project, with the hope that the authorities would understand what I was trying to achieve, and help me continue with permission. But my fears became true. Today, I cannot proceed with the work, even if I were to cover all the expenses myself. I hope that eventually I will be able to break this censorship, and return to Chernobyl in search of more historical artifacts.

What kinds of images were you looking to smuggle back? Which ones caught your eye?

Time mercilessly destroys everything in its path. I wanted to collect and save as much as possible. Sometimes there was nothing but trash in houses, but often they were filled with artifacts. Nothing was laid out clean on a table or on a shelf. They were scattered on the floor, beneath broken furniture, or buried under a thick layer of mud. I felt like an archaeologist, rifling through heaps of garbage in search of lost memories.

By creating an ID system for each house and family, I marked every house on a map using a GPS tracker. In small villages with around 100 houses I tried to explore every house, but in bigger villages I had to rely on intuition, as time and capacity of what I could carry was limited.

Could you pick out a particular image, or series of images, and tell us the story is behind it?

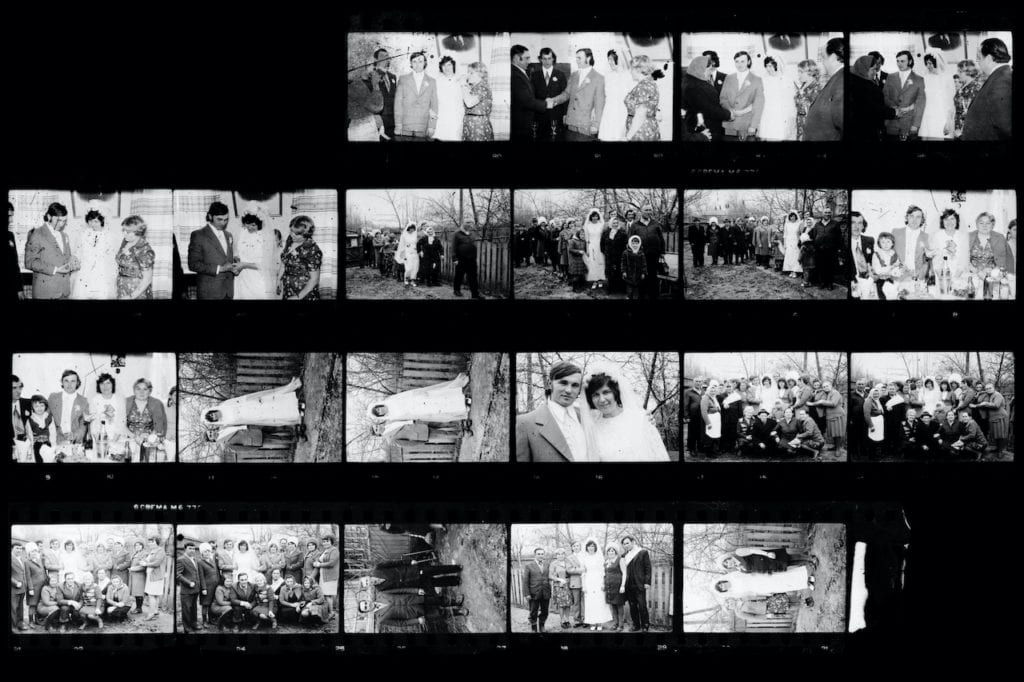

Each story is unique, but I’d like to talk about one of the houses, where a photographer lived. I believe he worked at the Dovzhenko Film Studios in Kyiv. His photo archive contains not only family photographs, like the other houses, but film reels and shots from photographing parades. I think a third of my archive is photographs and films by this man.

I found his house by accident in 2016, and was amazed by his huge archive. I wasn’t able to take everything with me then, as there was too much material and not enough time. I also didn’t use a GPS tracker back then, so I spent the next two years looking for this house. Even though I knew the village well, I couldn’t find it.

In 2018, on my last day in Chernobyl, I found the house. My friend Dima and I spent several hours rifling through heaps of trash and mud, trying to pick up pieces of the past. All the films and photographs were damaged, and some of them weren’t possible to save, but the majority of files were okay. I’m thinking of creating a separate story about the photographer’s family in the future.

You also took your own images of Chernobyl. Did the imagery you found inform your own image-making?

Finding the artifacts did not influence the visual language of my own images. Everything began with my photographs, and flight from the commotion of war. It was a departure from society, and immersion into my thoughts during long winter walks over abandoned territories, where nature gradually erased traces of human life.

When I entered the houses, I was entering the past. Photographs, letters, interiors, personal belongings — these all created an atmosphere of the past in the present. This time-crossing explores memory, territory, atomic energy, and nature. Sometimes, when I was there all alone, I had the feeling that I was in the future, and only from these little bits of history do I know that a terrible truth destroyed an entire civilization.

Why did you decide to show this work online? What are the benefits of showing it in this way?

I don’t think an online gallery is the best way to show this kind of project — I consider it more as a presentation. I finished the work during Covid-19, and following the example of other galleries and museums I decided to show it virtually. I envisage the final presentation as a physical exhibition and book.

In the future, if I have sufficient funding, I plan to create a website with an interactive map and digital archive of all the found materials. Part of them will be publicly available, and the private part will only be available only to the relatives of whom the materials originally belonged to. People will be able to go on an online journey through Chernobyl’s exclusion zone, and families who used to live there will be able to see how their house or village looks years after the disaster, and discover an archive of photographs and letters by their relatives.

Discover the virtual gallery here