On 04 April 2019, the number of deaths from coronavirus, COVID-19, in Italy surpassed any other death toll worldwide. A significant portion of these belong to Bergamo, a city in the heart of the Lombardy region, where there have been 10,000 confirmed cases and more than 2000 deaths; the actual numbers are likely much higher. The hospitals are heaving while the streets are empty; by many accounts, a sense of loss and mourning hangs over the province.

Freelancing in the field, filmmaker Francesca Tosarelli, who was born in neighbouring Emilia-Romagna and who lives in Turin, two hours from Bergamo, worked closely with Red Cross volunteers who were visiting individuals suspected of having COVID-19. In her footage, which was aired on Channel 4, arte, and Al Jazeera, Tosarelli captures the acutely ill as they struggle in the confines of their homes, unable to be admitted to the hospitals, which are already overwhelmed.

“One of the fundamental aspects of democracy is press freedom. I am a journalist and filmmaker and I have a duty to consider how to ethically document the crisis”

She also documented the ICU of a hospital in Ponte San Pietro, a comune near Bergamo, where the 300 beds are occupied by those suffering from COVID-19; there is no room for others who may require treatment. Nurses and doctors in hazmat suits, their names emblazoned across the backs alongside smiling faces, flowers, and hearts, rush around; meanwhile, an old stereo blares out music. Some are hopeful, others are broken by ceaseless death and illness.

Below, Tosarelli, who continues to cover the pandemic, discusses the ethics of being a visual journalist in the context of a pandemic, and her experience of documenting the impact of COVID-19 on the ground.

—

How do you navigate the ethics of documenting a crisis where the best course of action is to stay home — what is the importance of photographing it versus the risk it may bring to subjects?

One of the fundamental aspects of democracy is press freedom. I am a journalist and filmmaker and I have a duty to consider how to ethically document the crisis. A month ago, in Italy, the only imagery circulating was that which depicted empty streets and people wearing masks. I felt part of the story was missing, and I took the time to examine how to cover it safely with the necessary protective gear, and to understand what would be the right time and location. The concern is always how you do it — the process — and how you tell the story.

What was your experience of documenting the pandemic, particularly in such a highly-affected region?

I had no prior experience of covering a pandemic. However, I have experience of working in conflict zones and hostile environments — I have worked for years in Iraq, other Middle Eastern countries, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. I have also done hostile training, which helped, but covering a pandemic is something different. The pandemic affects us all — our loved ones, our families, our behaviour, and our actions have direct consequences on other people.

Through a few phone calls, and during the first day on location, I was trained by Red Cross volunteers — they taught me the protocol to follow in such circumstances: the type of protective gear to wear and to how to employ it; how to dress and undress; how to sanitise the cameras and the surfaces; the length of time it is safe to stay close to a patient who is suspected of having COVID-19 in a closed area, and when it is time to go.

However, my approach also mirrored that which I had taken previously, in that I practised strong journalism, followed strict safety protocols, and showed empathy and respect for my subjects.

How were you received by the people you were documenting?

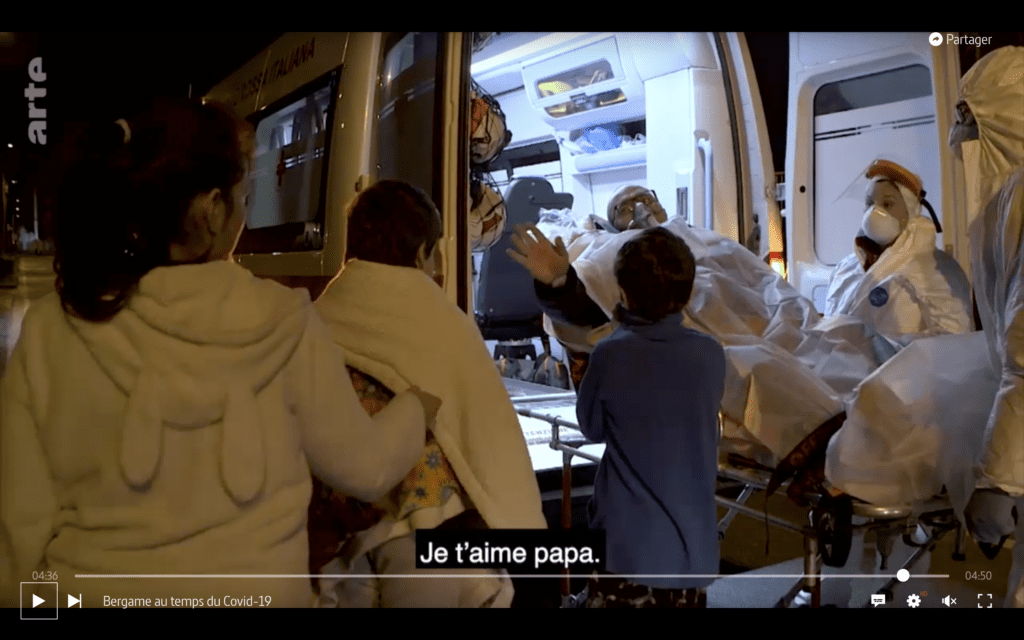

I was embedded with the Red Cross, along with photojournalist Fabio Bucciarelli, during their missions, we followed the ambulance. When we arrived at the patient’s home we were introduced by volunteers to the family members. That is a delicate moment because the situation can be dramatic for the patient and there are only a few minutes to explain everything: who you are, what you do, why you are there, and to explain and fill in the consent form.

It is a matter of empathy. The people I met immediately understood the importance of documenting the situation and welcomed us warmly. I spoke with them — they urgently wanted to communicate their stories to the rest of the world, which was still two weeks behind Italy. Many of them thanked us for what we were doing, and we have stayed in touch, communicating regularly.

That is the strongest motivation a journalist can receive – knowing that your message is useful.

“When we arrived at the patient’s home we were introduced by volunteers to the family members. That is a delicate moment because the situation can be dramatic for the patient and there are only a few minutes to explain everything”

What can photography and film contribute to our understanding of the pandemic, both now, and in posterity? How do you document something that is, by its very nature, invisible?

You document it through the stories of real people. Not only patients and relatives at home, nurses and doctors in hospitals, and exhausted funeral parlours, but also by visualising the consequences that the pandemic has on lives — showing how the virus has different consequences depending on one’s social class; exposing what it means to have public health for all or private health for a select group of the wealthy; documenting people without homes who have no place to go during a lockdown; emphasising how migrants without rights are forced to live during the emergency in even more dire conditions; and recording the unfolding economic crisis and the ensuing poverty, which millions are falling into.

What advice would you give to other filmmakers and photographers documenting the pandemic?

There are so many ways to document the pandemic depending on personal choices. If you want to be on the front line, it would be helpful to have some prior experience of working in hostile and distressing environments.

The best approach is to document what is close to home — securing strong access, working through the security protocol, remembering that if you have any contact with patients suffering from COVID-19, even while wearing protective gear, that you must self-isolate for 14 days in order to protect your contacts and those around you.

Do you think that coverage of the pandemic in the Western world, in countries like Italy, will contrast to coverage of developing countries, such as Africa?

My hope is that every place and every newsroom on earth will put freelance visual journalists in a position to practice good journalism and coverage of COVID-19 in a safe way. However, I know that it will not be like this. Unfortunately, we live in a world where not everyone is in the same position — I am not sure that my Congolese colleague will have the same health care insurance as my colleagues in the UK.

As a visual journalist, what do you feel that you can contribute to this moment? What is your responsibility?

My responsibility is to grasp the correct protocol of how to cover the crisis: to have all the protective equipment and respect the rules during and after shooting; and to act with sensitivity, empathy, and respect for people.

I will continue to document the situation through a character-based documentary film, which is an effective way of creating empathy and conveying important messages – putting people in the shoes of others to compel them to understand what is happening elsewhere.