In the first instalment of a new series, we reflect on projects made inside, including work by Gideon Mendel, Jerome Ming and Stefanie Moshammer

Due to worldwide regulations to stay at home during the coronavirus pandemic, many photographers are now making work from isolation, adapting their usual creative processes to make the most of their time indoors.

However, for many photographers, creating work at home is not a novel experience. From unpacking archival photographs, to working with materials found in their grandparent’s house and experimenting with energy drinks, the artists featured here regard confinement as an opportunity rather than limitation.

Oobanken by Jerome Ming

Jerome Ming has travelled the world. He was born in London and grew up in Zambia and Malawi, before returning to the UK to study photography. This was followed by a 20-year-career of covering stories all over Asia, as well as living in Singapore, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Myanmar and China. His most recent photobook, Oobanken, draws on this experience of constant relocation. But despite being based on his lifetime of jet-setting, the series was made entirely within a compound in Yangon, Myanmar, where the photographer lived in 2014.

As if confined in an enclave, Ming’s images combine fragments of personal history, of memory and imagination, building a narrative out of construction and performances. “I’m always living in a different environment, but the consistency is that I’m the one making the work, and I’m making it with a certain idea and central themes,” he says, in an interview with BJP. “Although my work might not look similar, I’m still feeding off the same premise in a way, which often tends to be a little about this dislocation.”

Cornelius de Bill Baboul: Thirsty, then boosted

What happens when you put a white flower in a vase of coloured water? It’s an experiment some of us might remember from our childhood, when we magically transformed a bunch of flowers with a dash of food colouring. But the results are a little more frightening in Cornelius de Bill Baboul’s experiment, in which flowers suck the colour out of sugary energy drinks. “I think they look a little bit like dancers,” he says, in an interview with BJP-online. “Like kids on ecstasy in a techno club celebrating the end of the world”.

When the French artist first encountered the brightly-coloured drinks he was equally attracted to and amused by them, because they reminded him of engine coolant. He’d buy a bottle, taste it, then display it on a windowsill in his studio, “it was just a funny object to have,” he says. Then one day the photographer was sent some flowers, and recalling his own childhood experiments, he put one of the stems in a drink. To his delight, the flower lapped up the sugary fuel, making the start of his series — Thirsty, then boosted.

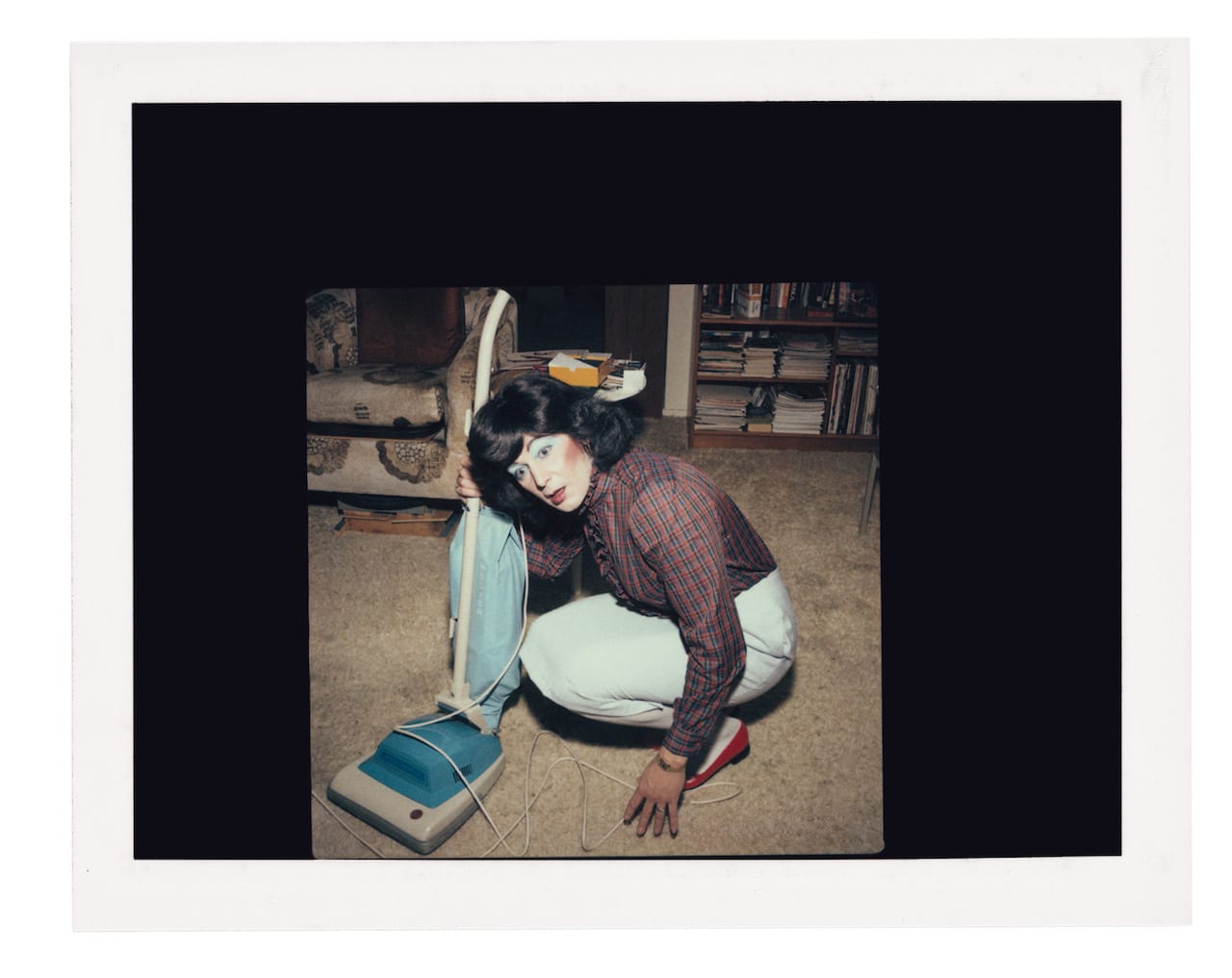

Stefanie Moshammer: because, Grandmother said it’s okay

The photographs that comprise Stefanie Moshammer’s dynamic project are not what one would expect. A series depicting a Grandma and Grandpa and their house in a sleepy Upper Austrian village evokes images of dated interiors, replete with trinkets and memorabilia. But, Moshammer does something different.

Working in her grandparent’s home, the photographer wanted to abstain from showing aging in a sad way. Assuming whimsical poses and sporting colourful costumes, it is clear that the project is not just about the lives of her Grandma and Grandpa. “It is a mix of different subjects and layers, which come together to create my point of view,” she says.

Over the years, the photographer has observed her perception shift and change: “I have seen things that I did not see before.” In that respect, the work also exists as a reflection of Moshammer’s life. “This is a place that has never changed,” she reflects, “it is me who is changing and that is why I feel differently”.

April Dawn Alison’s private portraits

April Dawn Alison was the female persona of Alan Schaefer – a commercial photographer who lived his life as a man in Oakland, San Francisco. After his death in 2008, an estate liquidator was hired to sell the belongings left in Schaefer’s home. In the process, he discovered 9,200 Polaroids made by, and of, Alison.

Several years after Schaefer’s death, the images were sold to a local painter who donated the archive to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Over a decade after Alison’s death, a selection of the archive was published in a book by MACK, and exhibited in a solo show at SFMOMA.

Made over the course of around 30 years, the images range from moody black-and-white stills to dynamic, colourful and humorous self-portraits — a long-term exploration of a non-public self, made entirely in the artist’s private home. “It is a way of seeing yourself as you believe yourself to be, or as you may not be in the world yet,” reflects curator Erin O’Toole, in an interview with BJP-online.

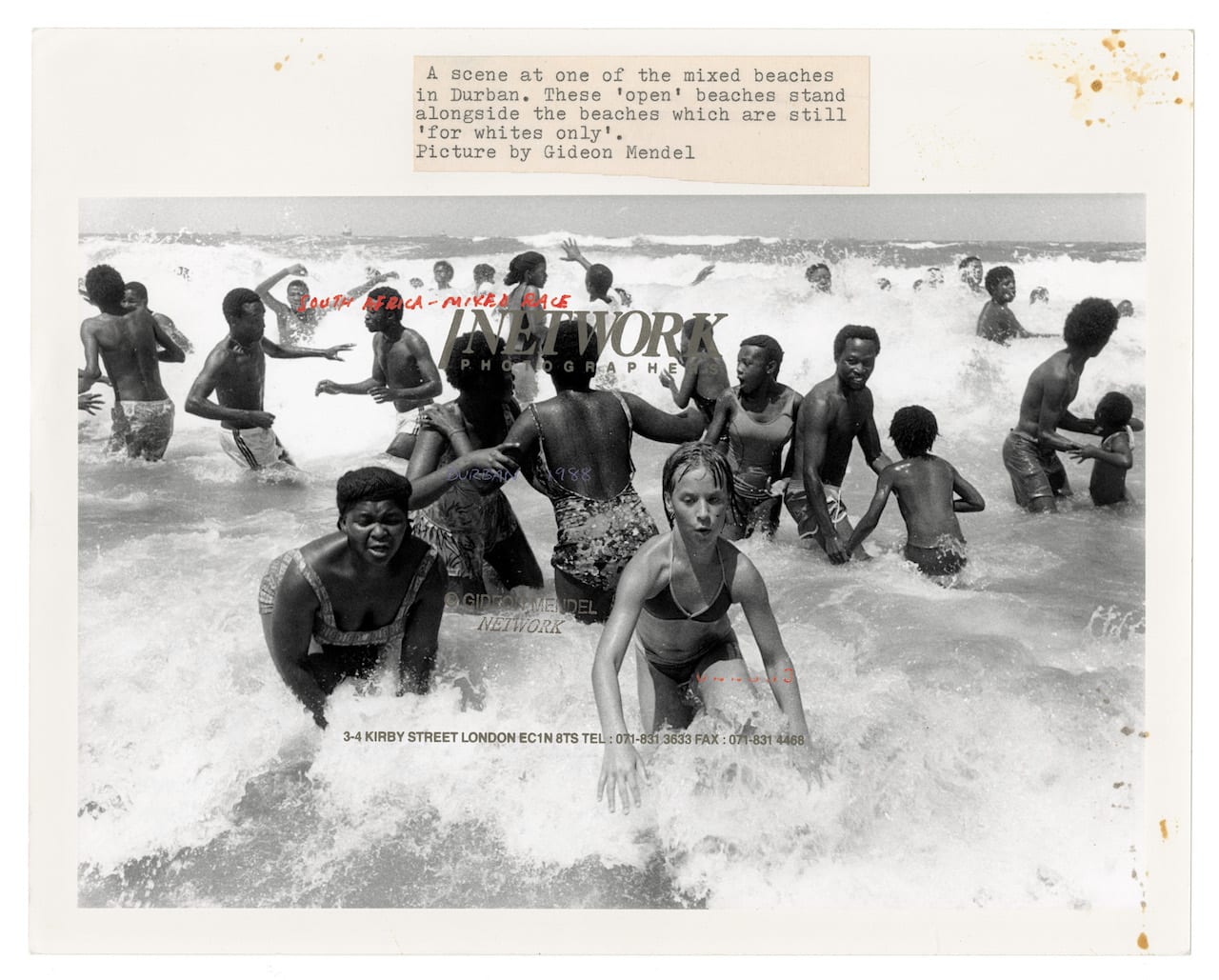

Gideon Mendel: Freedom or Death

When Gideon Mendel left South Africa in 1990, three years before the official end of Apartheid, he left a huge archive of transparencies and negatives in his friend’s garage. In 2016, 25 years later, Mendel learned that the top inch of one of the boxes had been water-damaged. Thinking there could be something interesting in this forgotten work, he decided to revisit the memories, and what he found were “radioactively charged” images from his archive of a tumultuous time in recent South African history.

These images, many seen for the first time, were presented in Mendel’s latest photobook, Freedom or Death. Split into three parts, each section is categorised by a different form of “intervention”. The first section presents the series of water-damaged negatives, which speak about the fragility and malleability of memory. The second section is a collaboration with Argentinian artist Marcelo Brodsky, who writes and draws on Mendel’s photographs to enhance their historical narrative. The final section is derived from press prints made during Mendel’s time as a news photographer. Mendel digitally merged the front and reverse of the prints, creating a superimposed combination of image, text, and markings.

Through this attempt to re-engage with these documents of history, Mendel was also able to re-engage with his own memories. “I’ve come to realise that to some extent I was packing away those traumas within myself, like how I packed away the boxes,” he says, in an interview with BJP-online. “Unpacking it has been an important process for me.”