This article was published in issue #7893 of British Journal of Photography. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.

Few people associate the golden era of studio photography with the small and recently troubled West African country of Mali, a place that, over the last decade, has made headlines for anything but. Nonetheless, Black Shade Projects, a new exhibition platform founded by curator Myriem Baadi, is about to establish a forgotten generation of Malian photographers into the history of the medium.

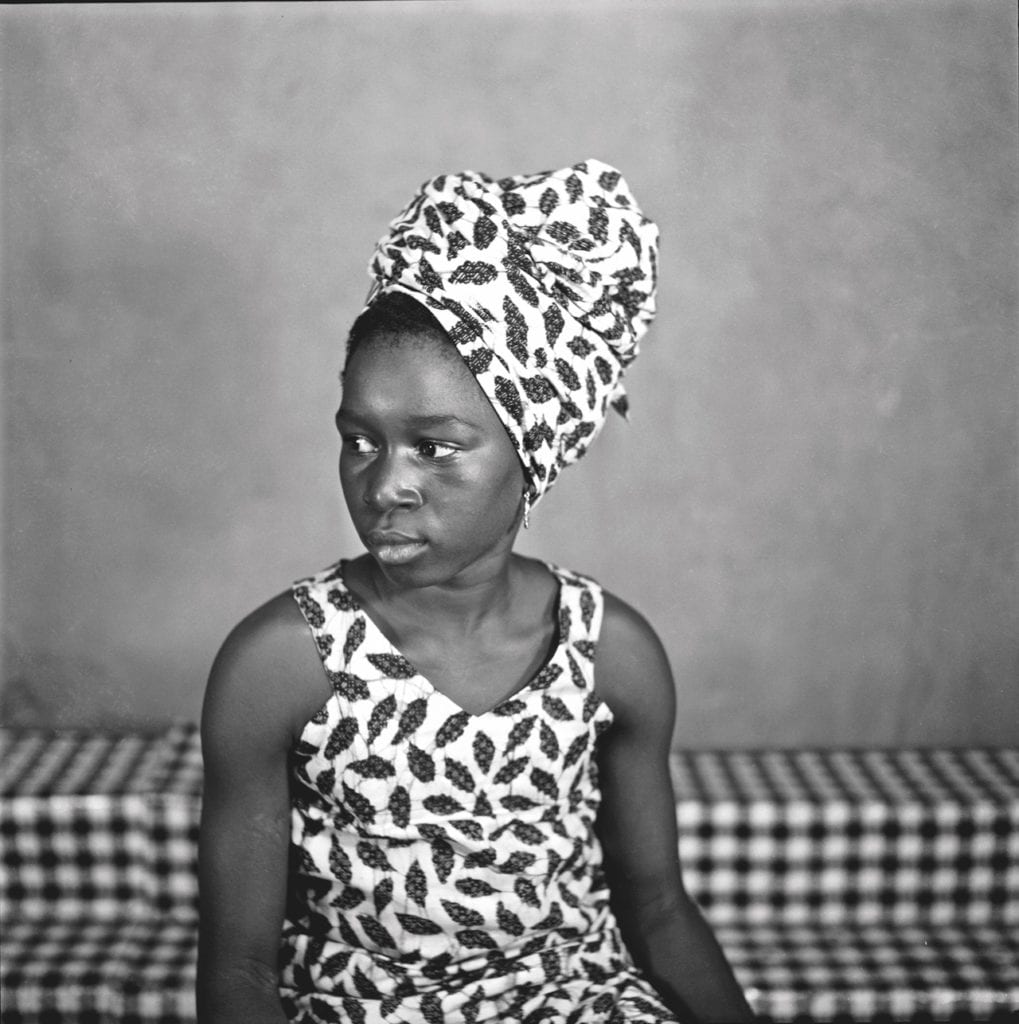

Without a physical space, and being careful not to align the initiative with the term ‘gallery’, the Black Shade Projects initiative first launched in autumn 2019 as a pop-up at Ozwald Boateng’s Savile Row tailors in London. The initial exhibition showed works by little-known Malian artist Youssouf Sogodogo. Titled Hairstyles of Mali (Les Tresses du Mali) and dating back to the 1980s, the series explored the shared culture and craft of female hair braiding.

Images from Hairstyles of Mali will also be on show in Morocco as part of Black Shade Projects’ first group exhibition. Opening on 19 February and showing at the Jnane Tamsna boutique hotel in the Palmeraie area of Marrakech, over the course of the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, and supported by the inaugural edition of AFR Eculture, the second exhibition will focus primarily on the more unsung work of African photographers Adama Kouyaté and Abdourahmane Sakaly. They are beautiful to behold, but there’s also a hard political edge to these portraits, the show’s curator, Lisa Anderson, suggests. “There are underlying tensions between sub-Saharan Africa and North, or Arabic, Africa. This show will make people confront these tensions, and explore where we’re at in that conversation. It’s an opportunity to face that challenge and get a sense of the resistance.”

Sakaly and Kouyaté were close contemporaries of fellow countrymen Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta, both Malian artists who have gone on to enjoy considerably more recognition from the global art market. But Sakaly and Kouyaté, Baadi says on a phone call from Marrakech, deserve comparable respect. Each photographer is a “treasure of history,” says Anderson. “Their images are time capsules; ways of uncovering personal histories that are at once familiar and then, at the exact same time, so foreign. They’re so ripe for modern exploration.”

The works of Sakaly and Kouyaté will be exhibited in close comparison to that of the more renowned Keïta’s work, shown at the same time in the entrepreneurial chaos of the souks. Titled Untitled: Seydou Keïta, and organised in collaboration with Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden and the Contemporary African Art Collection, the show will see large-scale photographic prints of Keïta’s work pasted on the walls of the Marrakech medina.

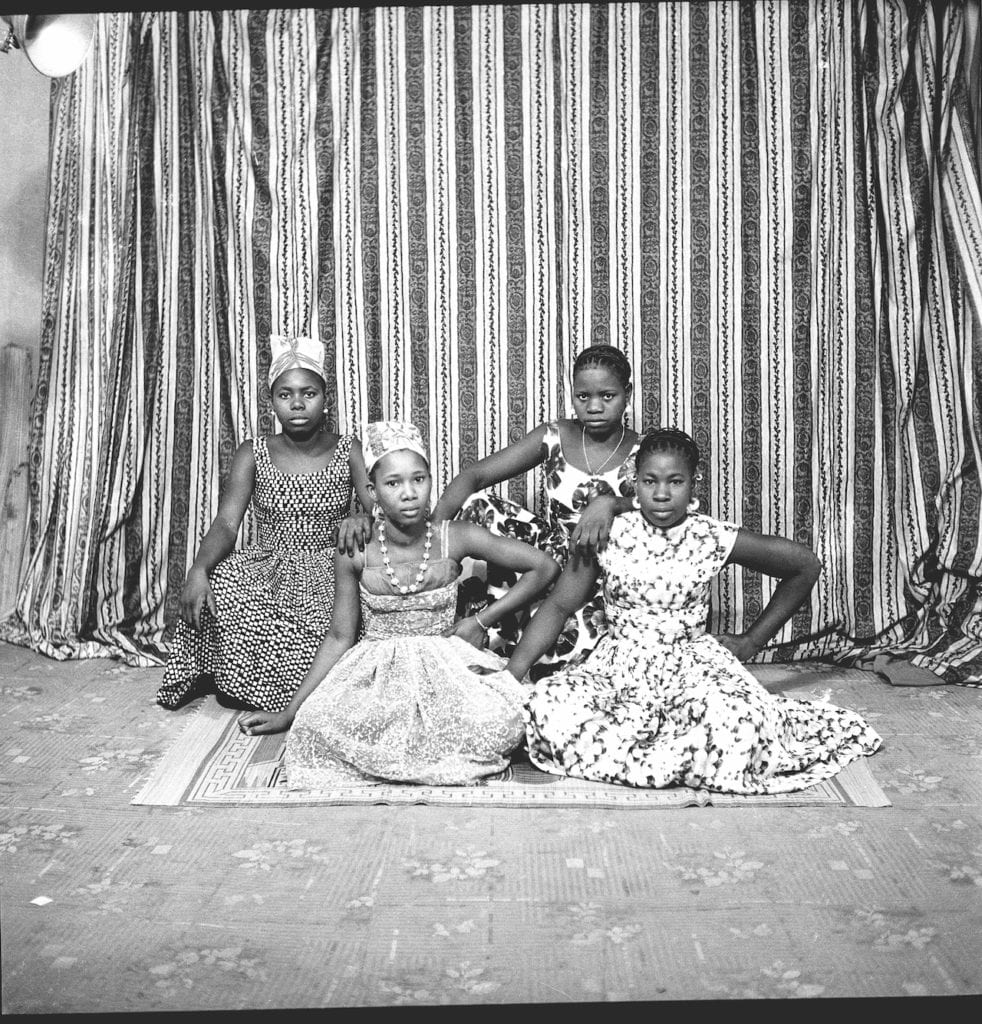

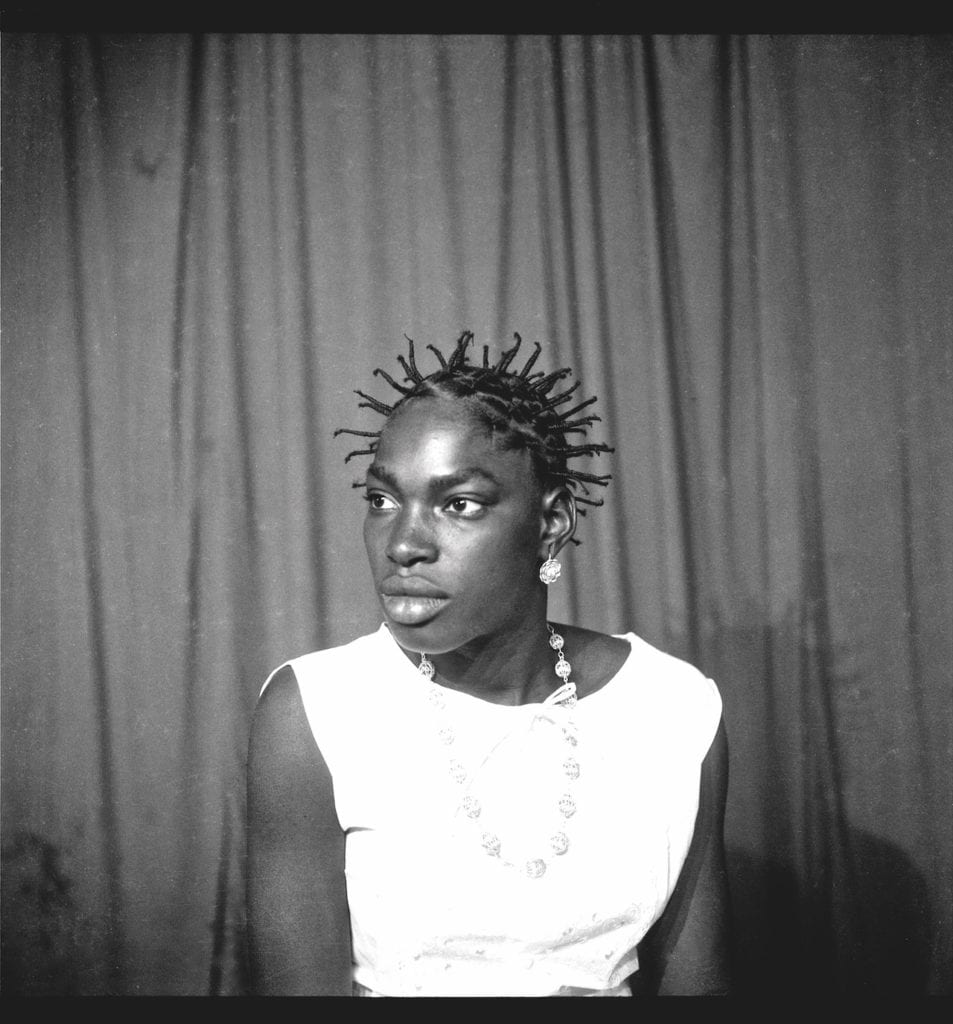

Keïta is perhaps best-known for his images of Malian families from the 1940s to the early 1960s, while Sidibé explored the raucous dancehalls of Bamako in the years after independence. In comparison, Sakaly and Kouyaté are significant in today’s climes for their sustained focus on the sole female subject. Their portraits offer contemporary viewers an education in how the black female gaze – and the black female body – were represented in hitherto undiscovered photographic cultures beyond Europe and North America.

“I hope to posit the show within the broader conversation of the portrayal of black women in contemporary art,” says Anderson, who is also the founder of art platform Black British Art. “I’m a feminist, and I love my black sisters, so the opportunity to try and reframe the way we understand the image of the African woman through time was too good to pass up. It’s powerful for me, as a woman of the diaspora, to look at these images and explore the power dynamic that existed between men and women – but manifested itself in very different ways to what we’re accustomed to.”

Sakaly and Kouyaté’s images of the female sitter are distinct in their usage of gesture, clothing, hair and accessories, and, most importantly, perspective – “the agency and power present in the female gaze,” Baadi says of the images. The portraits were taken in the years after Mali gained independence in June 1960 – “a time of immense change, hope, freedom and modernity which resulted in a blossoming language of personal expression, of stylised visual identity,” Baadi says. “Each subject embodies a unique set of experiences and aspirations, the possibilities of which are channelled through their eyes.” She adds: “For many and obvious reasons, these stories have been told by non-Africans, and I think it’s very important for them to be told from within.”

“We’re raised here,” says Anderson, who is of African-Jamaican descent, of growing up in Britain. “We’re fed a certain visual diet. We’re given a few of what the 1960s looked like, and what the 80s looked like. Unbeknownst to us, a whole world of experiences were happening across the globe that we have no idea of. We know about the UK in the 60s and 80s, but what was going on in West Africa at this time? To look at these photographs, and to feel the vibrancy, the confidence, the excitement, the freedom of these people, is a magical thing. It transforms your sense of history, and your place in it.”

Black Shade Projects x AFR Eculture is at Jnane Tamsna, Marrakech, from 19 to 23 February 2020.