This article was published in issue #7890 of British Journal of Photography. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.

After living in Europe for several years, Andres Gonzalez returned to the US in 2012, intending to develop a project about the experience of coming home and re-immersing himself in American culture. “When my partner [photographer Carolyn Drake] and I were living abroad during the Bush era,” he remembers, “it wasn’t a popular time to be an American. There was a lot of negativity. I really wanted to do something celebratory and forward-thinking about the US.”

Two weeks after his return, those sentiments came to an abrupt halt when a mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut left 20 six- and seven-year-olds dead, alongside six adults. “That coloured everything I was thinking about this country,” says Gonzalez. “The emotions from that day deeply embedded themselves and lingered for a long time. I began reading a lot about this type of violence, which led me to texts about masculinity and American mythology – writers like Richard Slotkin, but also thinkers such as Elaine Scarry, whose writings on the relationship between pain and language informed the way I thought about expressions of suffering.”

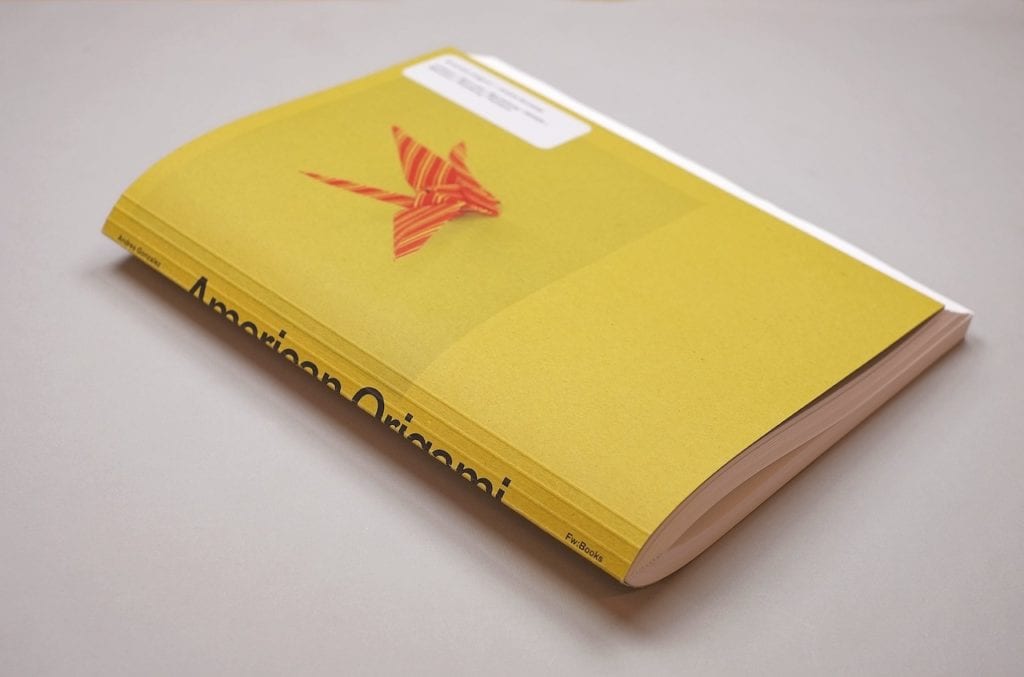

Heartache transformed into outrage and an urgent sense of purpose when proposals for universal background checks for gun sales failed in the US Congress a few months later. “I was absolutely appalled by our government. This pulled me deeper into the research, and it evolved from there,” he says. The resulting project, American Origami, reflects six years of research on the epidemic of mass shootings in American schools, beginning with the massacre at Columbine High School in 1999 and continuing with six of the deadliest school shootings that followed: Red Lake High, Virginia Tech, Northern Illinois University, Sandy Hook Elementary, Umpqua Community College, and Marjory Stoneman Douglas High.

These tragedies viscerally stir emotions of every type: sadness, fear, frustration, anger. That said, Gonzalez explains, “I knew that I wanted to present this work in a way where the viewer would engage with thought before emotions, or that emotions wouldn’t overwhelm the reading of the work.”

American Origami weaves together interviews, forensic documents, archival photographs, and press materials, as well as Gonzalez’s own photographs and texts, in order to “illuminate patterns hidden within this type of violence, to present a counterpoint to the conventional narratives from corporate media, private interests, and political messaging”. And while it is impossible to strip these events of their emotional potency, the book’s content is deliberately selected and sequenced to provoke thought and reflection rather than stoking those feelings often sparked by the sensationalistic images that dominate coverage of these events.

After months of research, in the autumn of 2013, Gonzalez made his first trip for the project to Northern Illinois University, the site of a 2008 shooting where five people were killed and 16 injured. “I hadn’t read too much specifically about Northern Illinois because I wanted to experience the physical place with fresh eyes,” he explains.

“A pattern emerged over and over again. These tragedies explode in prosaic spaces, but at the end of the day, they are erased and silenced from the landscape”

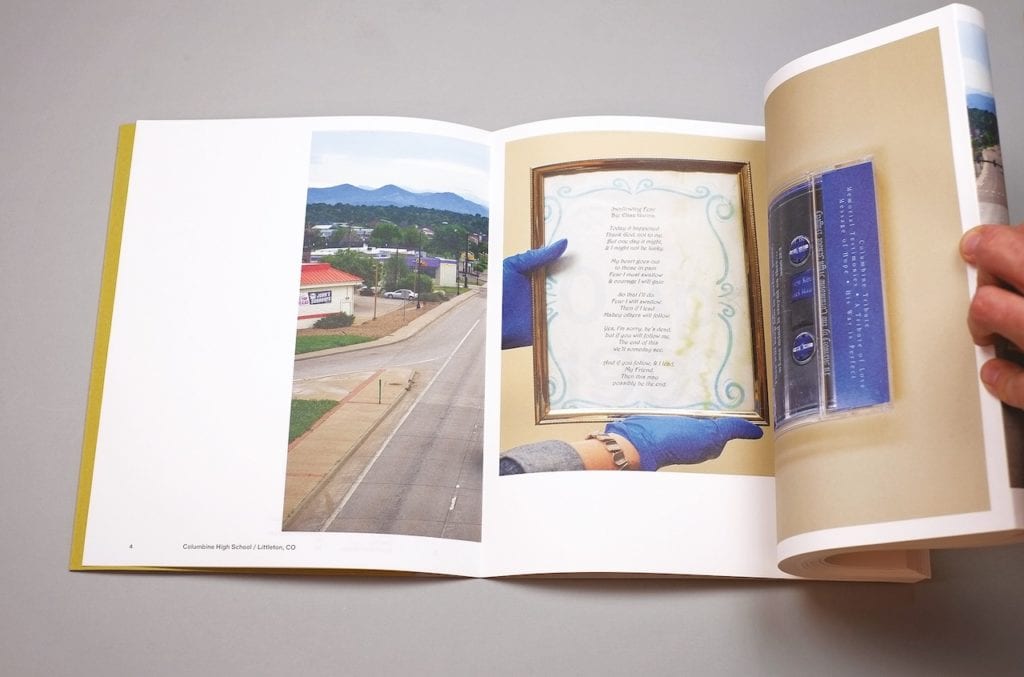

Gonzalez went on to photograph and visit the six other schools examined in American Origami, walking through both the campuses and surrounding neighbourhoods. His landscapes, almost always devoid of people, oscillate between serene and haunting. Pictures of the schools often punctuate chapters in the book, reminding us that these acts of violence are now inextricably linked to the way America’s young people experience educational institutions. As he visited these communities, he remembers, “A pattern emerged over and over again. These tragedies explode in prosaic spaces, but at the end of the day, they are erased and silenced from the landscape. And that is one of the reasons I wanted my landscape photographs to be quiet.”

Similar attempts to bury painful memories also appeared in the ways that communities dealt with the objects both collected from the sites of the shootings and sent to the associated cities, schools, or individuals. During that initial visit to Northern Illinois, the school’s librarian showed Gonzalez a seemingly endless catalogue of mementos preserved from the shooting. “I had known these items were saved, but I had no sense of the massive scale,” he recalls. “As I continued travelling to different sites and visiting their archives, libraries, or museums, I started to notice certain patterns, foremost being the pattern of preservation itself – the irony being how hidden these collections remain. There seemed to be a profound conflict between remembering and forgetting.”

Handwritten notes, photographs, artwork, flowers, religious keepsakes, stuffed animals, and origami cranes appeared in many of the collections – the latter ultimately inspiring the project’s name. Derived from the story of Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, which tells of a sick child who tried to fold 1000 cranes based on the Japanese belief that if she did, she would be granted one wish, origami cranes have become a universal symbol of hope and healing in response to disaster and suffering.

These artefacts speak about American grief rituals and human reactions in the face of such unthinkable trauma. “I didn’t know at the outset that these objects would end up becoming a focus of the project,” recounts Gonzalez. “Through the lens of these artefacts, I was able to look more deeply at some of the stories within the larger narrative and speak about something other than the tragedies themselves, a broader reflection on how we respond to and absorb violence.”

Gonzalez also integrated interviews (paired with subtle black-and-white portraits of the speakers) throughout the book to illustrate the lingering effects of these events in the aftermath. He struggled to arrange interviews as the majority of the people he approached declined to speak with him, many fatigued by the aggressive tactics used by the media. “A lot of these survivors, or parents, or friends who lost friends just want to move on; they don’t want to dwell on it. I was continuously seen as just another reporter trying to get the scoop. It took me a few years until I had something to share with people to demonstrate otherwise.”

The book does incorporate some stories from survivors, but it also includes other community members who share their recollections of the event and its long-term consequences. These interviews were carefully selected “because I didn’t want the same story told over and over again, or for it to feel like a series of war stories,” says Gonzalez. “I wanted to share the interviews along with the collection of artefacts in part to highlight the conflict between collective grief and individual experience. An engaged viewer will start to piece these various layers together to show the breadth of how these tragedies affect communities and individuals.”

After years of researching and amassing materials, Gonzalez made his first book dummy of American Origami in 2017. “I put it together in a way where the newspaper clippings were the focal point, interspersing them between the landscapes,” he recalls. “The artefacts were presented mostly as a collection of small thumbnails that were hard to see as individual entities. I included all of them so I could show the huge amount of material.”

Although Gonzalez liked this early design (which was shortlisted for the 2018 Mack First Book Award), the way people interacted with the book frustrated him. “As I watched people looking at it, they would just skip right over the newspaper clips. They would be so overwhelmed by all the layers of information, they wouldn’t engage with the texts at all. The book primarily became a visual experience. And I knew I didn’t want that. That’s when I reached out to Hans.”

Gonzalez turned to acclaimed Dutch designer, Hans Gremmen, for his advice on how to proceed. “I had known Hans’ work for a long time. I love how he uses texts and organises different layers of information in some of his books.” Gremmen remembers when he received that first PDF of American Origami. “I was immediately triggered by the whole project. And from that moment on, we kept talking and simply started working together.”

“There is this level of transparency with the paper. In some cases, you almost see through to the next page, like a ghost image. It isn’t treating the photography as sacred. It’s more like something you would print out from your home printer”

Communicating via email and Skype between Amsterdam and the San Francisco Bay Area, Gremmen and Gonzalez each weighed in on every facet of the publication, from editing and sequencing to the materials used. Their collaboration yielded a new edit of American Origami presented in an unconventional book form and published this autumn by Gremmen’s imprint, Fw:Books, and the non-profit Light Work.

“The main design problem was clear to me,” Gremmen explains. “It was balancing the various layers you see in the book. All of Andres’ material took up 400 pages in my first InDesign file. Two hundred pages were landscapes, interviews, and transcripts of the US presidents’ speeches from the press conferences that followed. And the other 200 were the artefacts. I realised that if we treated them in exactly the same way, they would neutralise one another, rather than making each other stronger. I knew I needed to look for a way to create these two parallel worlds in the book.”

Gremmen’s ultimate solution creates a book within a book by using an unconventional binding. A typical publication remains at the bindery for three to four days; with its unconventional binding, American Origami took two to three weeks to complete. “As soon as Hans came up with the binding, it just opened up the work,” Gonzalez recalls. “His design concept presented this exterior book of landscapes but then, right underneath the surface, you’d discover all this grief in these saved artefacts, and that added to the meaning of the work. Just as these items are hidden from public view in the basements of museums and libraries, they are hidden here, in the interior of the book. Unless you are looking for them, you wouldn’t know they exist.”

Working simultaneously on two InDesign files – representing the ‘exterior’ and ‘interior’ books – the duo edited the landscapes separately from the artefacts. Gremmen explains, “We knew we made two good edits. And though there were several deliberate anchor points throughout the book, when we integrated the two parts, we just wanted to see how things would land. In a way, it was organised chance. In a book where there were so many focuses, it felt very nice to let go in a few places.” Gonzalez continues. “I also love that the book references origami in the way that it folds into itself. As you unfold it, it starts to reveal some of its materiality.”

A viewer needs to flip through American Origami to understand the brilliance of this approach that marries form and content. The simple appearance belies the complexity of its production. It evokes a plain Manila folder, labelled in the upper corner and packed with sheets of paper overflowing from the top edge. Of the paper stock used, Gremmen explains, “There is this level of transparency with the paper. In some cases, you almost see through to the next page, like a ghost image. It isn’t treating the photography as sacred. It’s more like something you would print out from your home printer.”

The front cover features an image of a single paper crane. On the back cover, 145 stars represent the number of deaths from these seven shootings. A reference to both the American flag and the CIA Memorial Wall (a memorial for agents whose identities and deaths remain classified, who are remembered with a single star), Gremmen wanted to illustrate and emphasise the number of people who perished rather than allowing the total count to become another statistic.

A report from Media Matters for America found that major news coverage of the deadliest mass shooting in modern American history – the 2017 Las Vegas shooting – lasted one week. And this fleeting coverage tends to be true in the majority of mass shootings. The news breaks, victim stories emerge, the perpetrator and their motives are discussed, and a flood of thoughts and prayers clog the arteries of all media outlets. However, the overwhelming grief, confusion, and anger indelibly mark the affected communities.

And this is what American Origami shines a light on. Peter Read, the father of Mary Read, killed during the Virginia Tech shooting, poignantly articulates the enduring impact of these tragedies. “It’s this hole that’s ripped into the fabric of her family, her friendships, her community; and it’s a hole shaped like Mary, in every way you can imagine, and it goes on, forward in time indefinitely. And everything has to rearrange itself around that emptiness.”

American Origami by Andres Gonzalez is published by Fw:Books/Light Work.