“I had learned that the best way to make meaningful photographs, as a photographer starting out, would be to document what I knew best, what I loved,” says Emma Hardy, describing the beginnings of her photographic career. “Hence my family.” Images of home and family have always been a compelling theme in documentary photography, from Sally Mann’s poetic black-and-white images of her children to Richard Billingham’s pathos-filled portrait of his parents from the series Ray’s a Laugh. There is the seductive sense of a lid being lifted, or a magnifying glass held over a subject as relatable as it is specific; photographs of families, like families themselves, can take so many different forms and provoke so many different emotions.

This is the impetus behind British Journal of Photography’s new collaboration with Lucasfilm, Star Wars Families, a new commission that will see 10 photographers each create a narrative family portrait of 10 different families across five continents. The project will explore these families’ unique dynamics through the lens of Star Wars, and the impact that film and fandom have had across the generations. British Journal of Photography spoke with three photographers known for their projects about family to find out what makes an impactful family photograph, as well as the challenges and emotions their work provoked along the way.

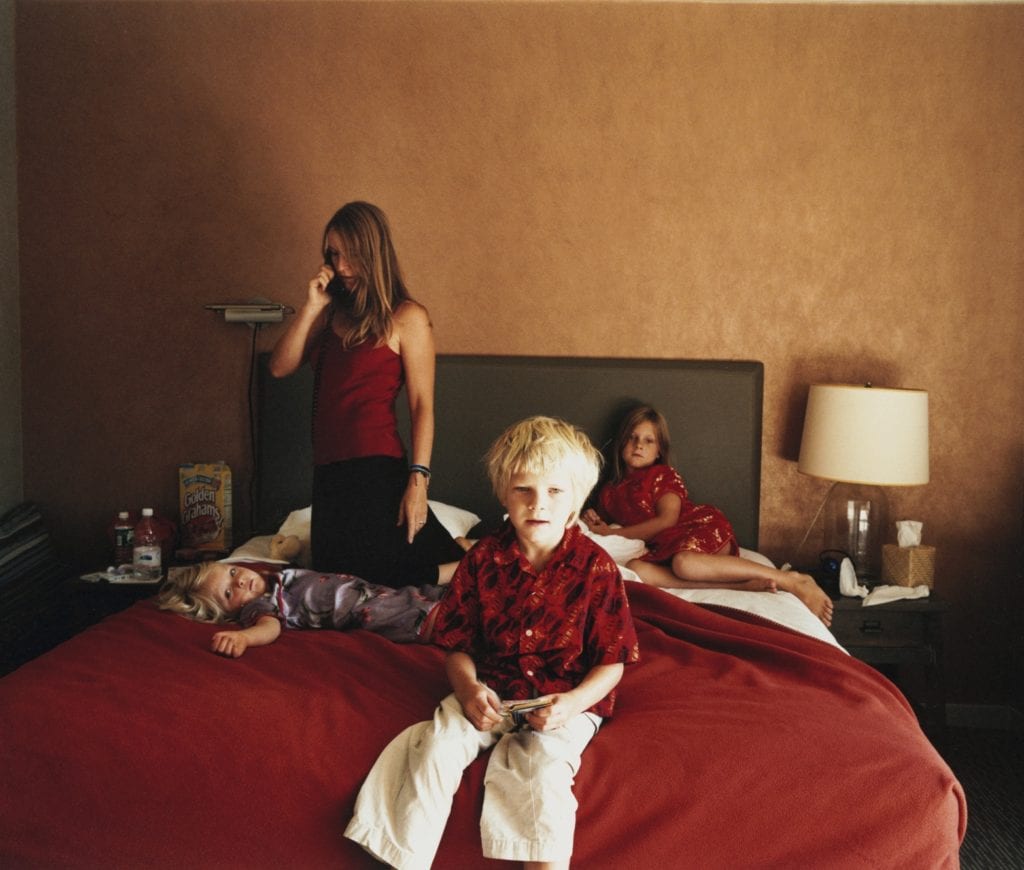

Hardy’s project Homework is a tender record of her family — particularly her mother and her children — made over the course of more than a decade. The images are deeply evocative in their use of light and rich tonality, even when depicting something as banal as a child watching television. In another image, the family are seen sprawled across a bed, Hardy herself included, constructing a photograph that is charged by the various relationships it depicts: the children meet our gaze, but Hardy does not.

Hannah Altman’s Indoor Voices is a series of constructed portraits of herself and her mother. In every image we see the pair sharing intimate spaces, often physically close. The tenderness and spontaneity of their relationship are palpable even within the context of a staged scene. Sadie Catt employs documentary photography to trace her lineage across the Atlantic Ocean to Canada, where half of her family still live. The starting point for the work was her mother’s poor mental health. “My intention was to help us understand each other, and what was happening in our lives at the time, while also providing us with something else to focus on — an outlet of sorts,” Catt describes. The project was a means to learn about her family line, and how it reflected back on the photographer herself.

“We can all relate to belonging to some sort of community, experiencing relationships and feeling curious, or impacted by our heritage,” says Catt, reflecting on the appeal of family photography. “I think working with the concept of family within photography enables work to be both personal and universal.” For her, the family narrative was a central theme of a project that also eventually explored the Canadian town of Woodstock: its agricultural background, the cultural roles people were expected to adopt there, and the conflict between the place being deemed ‘The Friendly City’ alongside its demographic problems with crime and poor mental health. Her own family became a prism through which to explore these issues, as well as a starting point for introductions: her cousins led her to other Woodstock locals, in a network that opened out from this family nexus.

For Hardy, Homework was also “a very specific witness of some of the moments in my children’s earlier years that I’m grateful to have captured on film.” Her lens reverently records small moments that may otherwise be lost to time. For Altman, too, time is a crucial aspect of the work. “I think the series really benefits from having time to breathe,” she says, describing the process of making around six images with her mother per year. “I am still learning so much about [Indoor Voices] as it continues.” Photographing the family can be incredibly fertile ground, producing new yields as the years unfold. “At the very best, it’s a combination of intent, heart, response and reward,” notes Hardy.

Inevitably, work that addresses the family points to the person behind the lens, and the role they play within the family constellation. Photographers making work about their own families cannot avoid including themselves, even if the camera doesn’t depict them directly. “I did a fair bit of growing up [in Woodstock], both as a young woman and a photographer,” says Catt. “I think the gradual transformation of this body of work reflects that.” Catt’s vision of her maternal line ends with her, the photographer, visiting a town under heavy snow for the first time.

Hardy watched through her lens as her mother grew older and her children grew up, moving away from the home they’d all grown up in; the images bear witness to this process, reflecting the emotional and psychological states of the photographer herself. “It’s as much a document of my own life and its emotional content as it is an exercise in pinning down fleeting moments in the lives of my family,” says Hardy. For each of these three photographers, there is a strong element of discovery or searching within the work, both of self and of shared blood. For Catt, this latter point took on the most literal sense. “I spent time with people, strangers to me, who had known my grandmother; I never had the opportunity to meet her myself,” she says. Woodstock was a very genuine means of encountering facets of her family that were previously unknown. “Making this work has been hugely enriching,” she says.

Just as the family dynamic is imprinted in the photographs, the presence of the camera itself can have a profound effect on the family dynamic, changing the nature of the relationships it purports to depict. Altman found that her project informed her interactions with her mother as they collaborated over the years. “This work has really deepened our relationship,” she says. “I think the arranged nature of the project is an aid in that because it blurs the lines of our lives inside and outside of the frame. I think that thin veil of composure allows us to more freely explore stories and process our own narratives.” The proximity that Hannah records — the hands interlinked, the bodies pressed together, light dappling itself across both of their faces — is suggestive of the creation of an internal space of learning, available to only the two of them. “I’ve grown to appreciate that the only thing directly influencing the project in the frame is time passing outside of the frame,” the photographer explains.

Hardy, too, found her depiction of her mother altered the timbre of their interactions, at least for a time. “In the moments of photographing her, I became somewhat removed, more objective, more able to distance myself from the labyrinth of emotions that surround our relationship,” she describes. “There is a different psychological charge to the pictures I’ve made with her compared to our relationship without a camera between us.” What the photographs show, then, is a braided record of truth and the transformation of relationships — the camera inextricable from the emotions and bonds it documents.

Making work about families, whether your own or others, requires delicacy, something that Altman, Catt, and Hardy were conscious of as they approached their respective projects. “The most important thing to consider when making work around families is the impact that the making and potential sharing of that work will have on anyone involved,” says Catt. “It’s something that should be approached with sensitivity, commitment and a large amount of ethical consideration.” In her case, dealing with subjects such as mental health, this ethical aspect received particular emphasis. “I still debate how much to share,” she says. “By focusing your camera on people you are making them vulnerable so, as the photographer, you are responsible for their wellbeing.” After all, documenting the family has implications that reach far beyond the naive record-making of smiling pictures in family albums. It is a way of exploring one of the cornerstones of any person’s existence, and of navigating one of the most formative group relationships a person can experience. “It is so crucial to take the familial and the intimate seriously, as artworks with profound meaning and applications,” agrees Altman.

The lessons learned from pursuing projects about one’s own family can be applied outwards and to the rest of one’s photographic work. Hardy finds that her family pictures have informed the rest of her image-making, whether that be other personal projects, editorial portraits, or even commercial shoots. “They are a cornerstone for the way I approach all my work,” she says. “I hold the same charged sincerity as I photograph others: attempting to find humour, intimacy, quirkiness, or a reflection of that which is often missed or overlooked.” Photographers commissioned for Star Wars Families will be tasked with making a record of one specific family during a very short period of time, and the lessons learned by these three women in their own photographic work are instructive. “My advice would be that you must be clear and concise with people about what you are looking to explore, or any intentions you have for the work you are making,” says Catt, “continually checking in with your subjects, and their feelings or concerns around the project.”

This empathetic quality is something that Catt, Altman and Hardy all share, and could be regarded as a hallmark of successful family documentation. “Photographing immediate or close family is an intimate responsibility and is best handled with benevolence and courtesy. I think the same applies to photographing someone else’s family,” Hardy agrees. “To me, the most important photographic principles are honesty and tenderness,” she goes on. “Honesty with yourself and tenderness with your subjects. Staying close to your heart, and as close to the truth as the camera allows, is the best advice I can give.”