Felix Hoffman, the chief curator at C/O Berlin, moved to Berlin in 1997. As a young art history student, Hoffman recalls pinning a schedule to the inside of his apartment door during breaks in his studies. The schedule detailed the different club nights happening over the forthcoming week. “It reminded me where to go on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday,” he remembers. “This was a time when clubs only opened once a week or every second week — it was a secret system, and it was an important experience for me when I was younger.”

No Photos on the Dancefloor! Berlin 1989-Today, a new exhibition opening at C/O Berlin, is curated by Hoffman and guest curator Heiko Hoffmann, and charts the evolution of the Berlin club scene over the past 30 years — beginning with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and ending today, in a city threatened by rising rents and rapid gentrification. Comprising photography, film, and archival material, the multi-layered show endeavors to explore the many facets that comprise Berlin club culture — from its social and historical significance to the intimate experiences of individual club-goers. “I would not have co-curated this exhibition if I had not had this personal experience as a young student in Berlin,” says Hoffman.

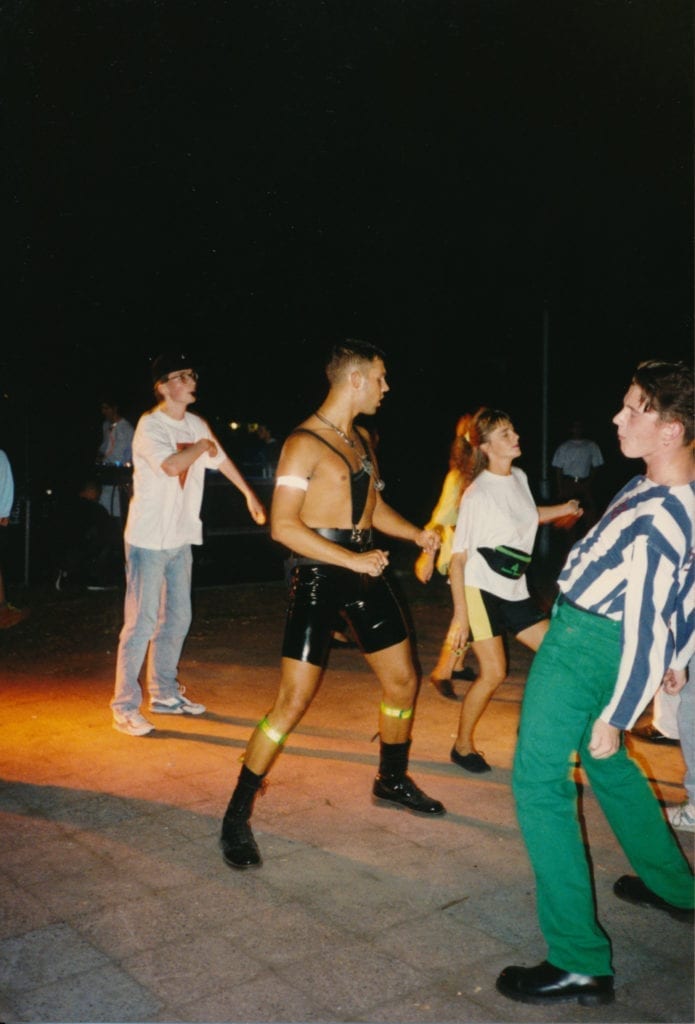

In 1989, the fall of the Berlin wall precipitated what is regarded by many as one of the last major youth culture movements in Europe to date. The end of this physical and ideological divide gave rise to a surge of creativity, which manifested itself in the empty and abandoned spaces on the fringes of former East Berlin. A new kind of club culture rapidly emerged, forming in opposition to the strictures of post-War Berlin and characterised by transience, openness, and the new electronic music around which it formed. A sense of community and inclusivity were central; financial success was irrelevant — the majority of spaces remained open for just one or two days each week, allowing the people behind them to attend other nights. “People would just enter a space,” explains Felix, “they brought in music, they brought in TV screens, perhaps the work of young artists employing new media. This is something that cannot happen when everything is fixed, and rents are high.”

Ufo, Planet, Tresor, E-Werk, the first incarnation of WMF, and Elektro emerged as the legendary party spaces of early to mid-1990s Berlin, paving the way for a new wave of clubs in the early 2000s: Berghain, Bar 25, and Watergate. “We were entertaining the possibility of putting together a show about `East German photography,” says Hoffman. “But, then we thought about how the energy of the club culture system has been so important for Berlin over the past 30 years — it was this kind of special feeling that has evolved, and which should be visible in the exhibition.”

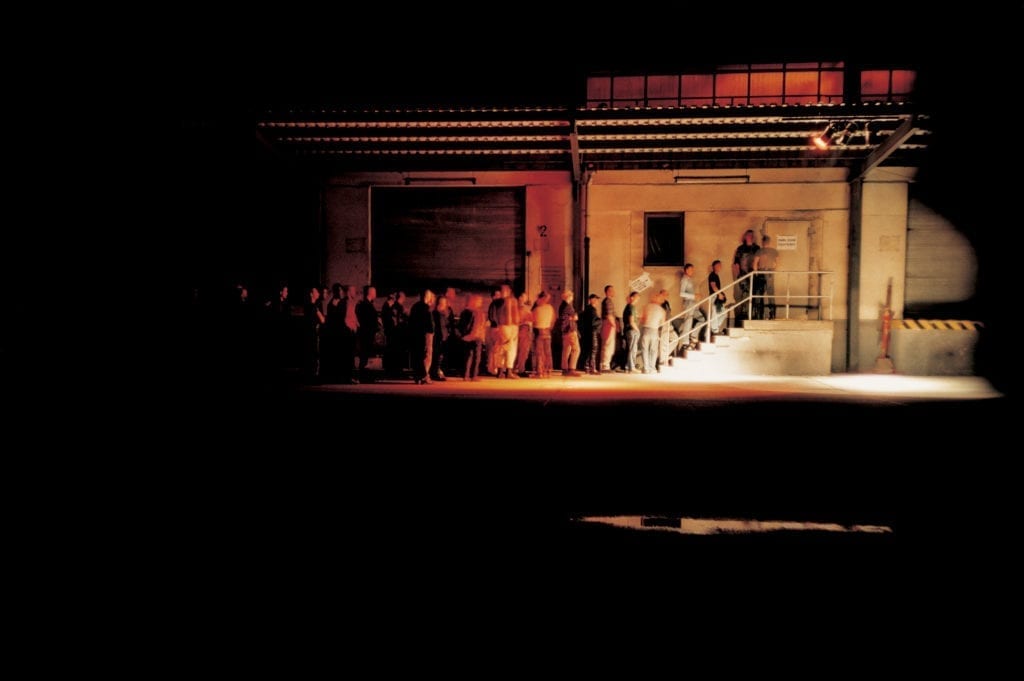

But, how to make visible three decades of a club culture that has fiercely resisted documentation? “No Photos on the Dance Floor!, refers to a particularity of the Berlin club scene: photography is banned in almost all the important clubs,” explains Heiko Hoffman, in the catalog that accompanies the exhibition. “This dates back before the days of smartphones with high-quality digital cameras.” Today, as party-goers enter Berghain or newer clubs like ://about blank, a large, circular sticker is applied to all phone cameras; the sanctity of the dance floor as a space for personal experimentation is protected. In an era of mass surveillance and the ubiquity of the smartphone, Berlin’s clubs have erected a protective “border” of sorts.

And it is this atmosphere that the exhibition endeavours to embody. Comprising a range of media by artists including notorious Berghain bouncer Sven Marquardt, and long-time manager of the former MARIA Club and Eimer Ben de Biel, the works on show depict three decades of club culture from a range of perspectives. “We really tried to find pictures that do not show the events on the dancefloor,” says Felix Hoffman, “that space should exist as an empty field, a void; something you cannot see, something that should remain a secret.”

One image by Wolfgang Tillmans depicts three friends slumped outside a nightclub in the bright morning light, while another captures the hazy silhouette of club-goers queuing to enter Snax Club. “What has always made my nightlife pictures different, I believe, is that they come from the perspective of a participant,” explained Tillmans in an interview originally published in Berghain: Art in the Club, which is featured in the exhibition catalog. “You change your point of view for a moment and think: I’d now like to translate that into a picture.”

Playing host to DJs, and audiovisual artists from Berlin’s club scene, by night, the exhibition space will transform. “It was very important for the gallery to become a club during the night,” says Felix, who hopes that experiencing the show in this way will encourage viewers to engage with the work in new ways. “One of the most important elements for me, as a curator, would be that some people begin to dance, rather than being frozen in front of the work,” he says.

No Photos on the Dance Floor! Berlin 1989-Today opens at C/O Berlin on 13 September and will run to 30 November 2019.