“You tell a story differently when someone is listening,” reflects Susan Meiselas – the Magnum photographer who has chronicled some of recent history’s most complex upheavals and events in remarkable depth. From her coverage of the 1978 Nicaraguan revolution and human rights issues across Latin America, to her exploration of the Kurdish diaspora, past and present.

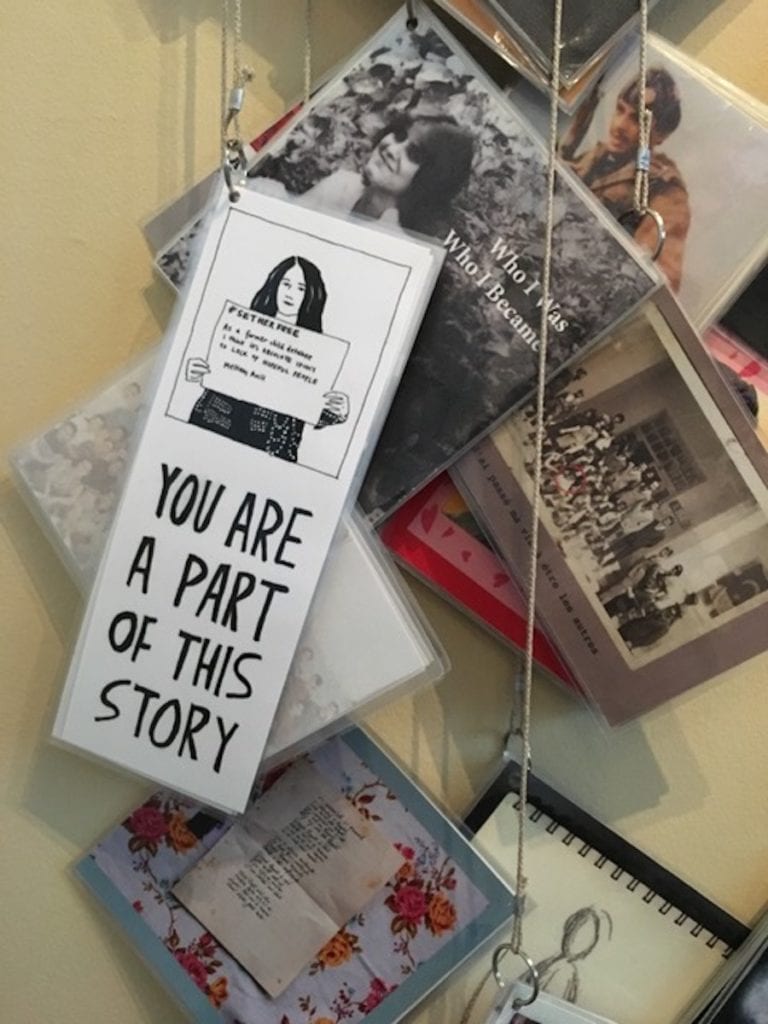

It is a grey Saturday morning in March and a small group of ‘listeners’ have collected in the cafe of The Photographers’ Gallery, London, to participate in a weekend-long storytelling workshop. The purpose of the event, led by Meiselas, is to uncover, and record, the stories of Kurds living in the capital – the London-based chapter of an ongoing project to gather memories from members of the Kurdish diaspora. Each exchange will potentially be translated into a physical booklet and affixed to a borderless map, displaying the stories and memories of nearly 100 contributors from the Middle East to Europe. The workshop coincides with the opening of a group exhibition featuring the four projects shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2019. Meiselas has been shortlisted for her retrospective exhibition Mediations, which featured four decades of work including a selection of her Kurdistan work.

But, as the morning progresses, no one arrives. Meiselas is undeterred. Throughout her career, the photographer has worked in tandem with history. A fixed and directive idea rarely dictates her work, rather it shifts and evolves as she delves deeper. In 1991, Meiselas arrived in Kurdistan. As was the case in Latin America, where she had spent over a decade before, it was the terrible significance of the events playing out that compelled her to go. “There was the same urgency and necessity to witness,” she explains in On the Frontline, published by Thames and Hudson, 2017. “Again the calling had to do with the fact that something horrific had happened, and again the concept of the project evolved in the field.”

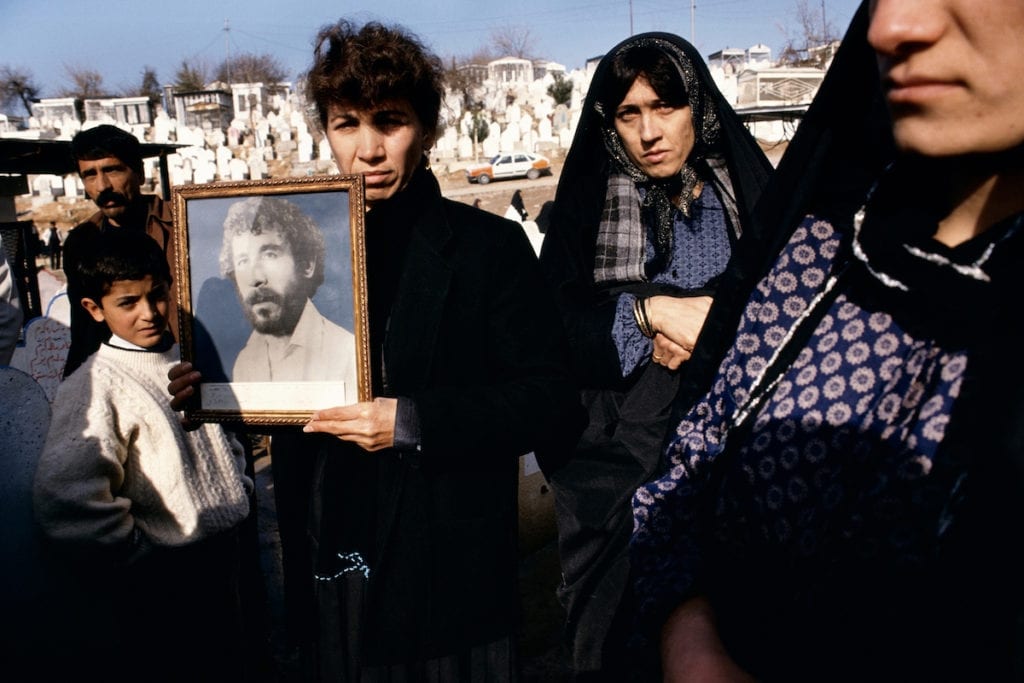

Meiselas captured the devastation and death wrought by the genocidal Anfal campaign perpetrated by Saddam Hussein – from the exhumation of mass graves to the ravaged ruins of villages abandoned by Kurdish refugees fleeing to Turkey and Iran. “I had not seen any visual representation of what had happened at that time,” she explains. This compelled Meiselas to go further – to excavate the fragmented history of a group perpetually denied their identity. “In Central America, I was capturing the protagonists in the streets making history,” she says. “I could not photograph in the present, what had happened in the Kurdish past, so that led me to begin a search for the work of image makers who had come before me.”

Meiselas embarked on six years of research into the photographic history of the region. She collaborated with the Kurdish community, along with drawing on a network of scholars and researchers. “[…] making my own images became less of a focus than reproducing the photographs I was gathering with the community,” she says. “I was repatriating the pictures I found in western archives and they began to contribute photographs from their own family collections.” The resulting book, Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History, which spans 100 years, exists as an archive of sorts – a space to collate the fragmented history of a community endlessly denied one.

Back at The Photographer’s Gallery, as the workshop progresses, participants slowly emerge. Despite the storytelling set-up, the process is far from linear. “It is not looking for stories to select,” says Meiselas, “but responding to what people offer and bring with them and feel ready to share publicly. I like to suggest that it’s a story that you would want to tell your child or a total stranger.” The exchanges are often long and meandering. The challenge for a listener becomes how to select the most significant strand and help translate it into a printed text. “The role [of the listener] is critical, to hear and help shape a story for others to read,” she explains.

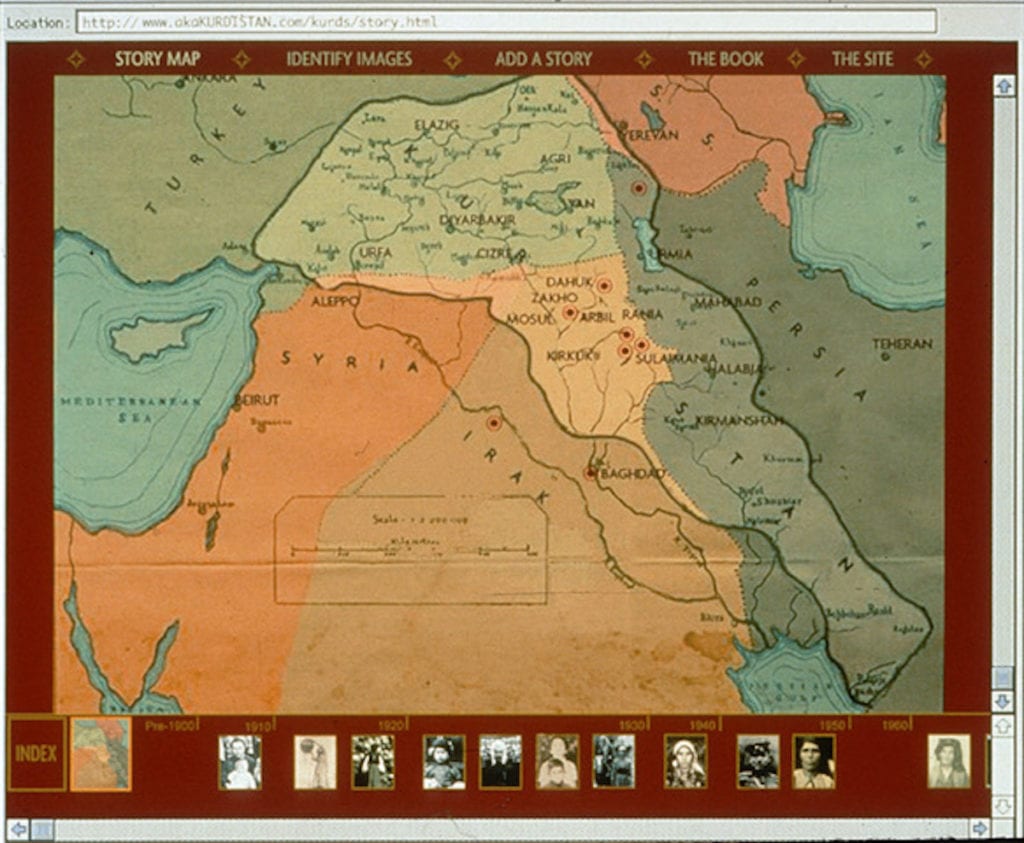

Originally, the workshops developed in tandem with akaKurdistan – a web-based extension of the book Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History. Founded by Meiselas in 1998, the platform provided a home for unidentified photographs unearthed during research and a place where people could contribute new stories. Meiselas also began to collect memories and photographs from the Kurdish community living in exile in each location that the exhibition was installed, in a new venue. It traveled throughout Europe for eight years.

Today the process feel unique. So much of human interaction takes place in the digital realm that the opportunity for such exchanges is rare. In the following interview, Meiselas discusses the workshops’ significance and the wider Kurdistan project of which they are part.

–

How did you translate such a multi-faceted project (the book, the website, the map, etc) into an exhibition? What elements did you want to draw out?

The first venue for the Kurdistan show was at the Menil Collection in Houston, just before the book was published, as part of FotoFest in 1996. I wanted the artefacts to be individually framed as I saw them as survivors, each one carrying a distinct story of who was in the photograph or who had taken or preserved it. The installation drew on the structure of the book, through the focus on geography and chronology. There wasn’t a website at that time.

The website grew out of the show traveling for the next eight years throughout Europe. It was hosted by diverse cultural spaces, such as the Netherlands Foto Museum in Rotterdam or the Museum of Ethnology in Frankfurt. I began to collect site-specific stories from the Kurdish community living in exile, who came to the museums with their own photographs and stories. We included their photographs on the walls, and then the museums scanned and uploaded them onto akaKURDISTAN—no one had a smartphone at that time. Seeing those contributions inspired others to participate.

Other elements on exhibit now at The Photographers’ Gallery were added when the International Center for Photography did my first survey show in 2008. The four-channel projection seemed important to help viewers relate to the process I had become immersed in. It was drawn from my book introduction and was designed by Jeroen de Vries.

The StoryMap is now another transformation to integrate the stories from the original website to expand the exhibition.

Collaboration is central to your work – opening up what could potentially otherwise be subjective and straight-forward documentary projects. Why is it important to use photography as a platform for exchange?

Collaboration has always been very important to me personally over the course of my practice as a photographer. I began thinking about the participation of the ‘subject’ in my first project– 44 Irving Street – and again, bringing voices to counterbalance my images in their representation, with Carnival Strippers. Each time the dialogue with the camera opens up more questions that lead me to consider alternative ways of inclusion.

How did you develop the idea of extending the Kurdistan project through the Storymap?

akaKurdistan was originally founded as an expansion of the book in 1998. It functioned as a borderless space to contribute to the collective memory for the Kurds who have no national archive or secure homeland. Initially unidentified photographs found during research for the book and images were uploaded by me or submitted online to an ‘unknown image archive’ section. This was along with an open ongoing invitation for contributions to share new stories by sending short texts to complement images.

At first a map of the proposed homeland for the Kurds from 1985 was printed on canvas and a group of stories that had been sent to the site were hanging as physical booklets connected by hooks to the places that seeded those memories to be held and read by visitors.

When the exhibit went to Istanbul, the map of Kurdistan was censored and I was told that it could not be shown. So I shifted the strategy and chose to paint a borderless map on the wall, from the Kurdish region to Europe where the diaspora now lives. This is what I call the ‘Storymap’ now which is endlessly evolving.

Are there any particularly memorable exchanges that you have had during these workshops?

One of the remarkable stories that we heard in Barcelona was from David who is Catalan and Mukaddes who is Turkish. They accidentally met in a Yezidi refugee camp, where Mukaddes offered to translate for David so he could better connect to people there. After that encounter, they kept in touch. A few months later Mukaddes lost her job as a school teacher due to growing political tensions. David suggested she visit him and got a visa for her to leave. Within a few more months, they married!

Another very poignant exchange for me was with a recent refugee to Frankfurt who was from the border of Turkey and Syria. At first, Bilal did not want to talk at all. He just kept obsessively looking at his cell phone. Finally, I asked to see his screen and he showed me pictures of his destroyed home town. Slowly the story of his flight unfolded. He was carrying his memory and family album alone with only a cell phone to connect him.

I read that initially much of the material was sent by contributors. What is different about hearing the stories of people in person?

Working with someone in person you can draw out details of their story or experience, more fluidly, their thinking than just corresponding by email. Originally I sat for hours in people’s homes or backyards looking with them at their family albums. Receiving uploaded images from strangers is totally different, and yet a kind of relationship linked us. The workshop is again an intimate setting and creating the little booklets together makes it special and placing it on the map makes it an even more meaningful gesture.

Why do you think it is powerful to present the stories, memories, and experiences of individuals in these physical booklets, particularly in the digital age?

Seeing the stories in physical form and holding the booklets invites the attention of the viewer in a way that reading on a screen or phone does not do as well. We are too often overwhelmed by digital demands and oversaturated with social media.

What do these personal narratives contribute to the history, and contemporary understanding, of Kurdistan that more official histories do not?

Most official histories are only one perspective, they often don’t include the daily lives of those most impacted by dramatic events. We need to hear those voices.

Do you think there will be an endpoint to this project, or will it continue to evolve and expand?

I don’t think about end points. I only wonder how relevant their past history will be to those who have lived it or those who are discovering it for the first time. I hope to continue gathering and perhaps expand the Storymap to a space where the surrounding walls will be full of stories from around the world which would best express the reality of the Kurdish diaspora today.

What do you want viewers to take away from the Storymap and the Kurdistan project more broadly?

A deeper appreciation of the experience of the Kurds and others who have had to flee their homelands who face unpredictable conditions with no safe return.

Susan Meiselas is nominated for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2019, which is on show at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, until 02 June 2019. The winner will be announced on 16 May 2019.