It is 1668 in Älvdalen, a small parish town in the narrow valleys of rural Sweden surrounded by thick forests. A 12-year-old girl named Gertrud was accused by a local child of walking on the waters of the river Österdalälv that runs through the valley. Along with 19 other women and one man, Gertrud was trialed and executed for practicing witchcraft. So began the brutal history of the Swedish witch trials, which triggered similar hearings across Europe, and, most infamously, in Salem, Massachusetts.

But Älvdalen is a mysterious town for other reasons too. Its native language is Elfdalian, a north Germanic dialect derived from the Viking’s Old Norse. Over time, the speaking pool has dwindled due to the government enforcing Swedish as the nation’s official language. Today, less than half of the town’s population – which is just over 7,000 – can speak the native tongue. How Elfdalian ever existed, and how it was preserved and isolated to a small trading town, remains a mystery.

For three years, photographer Maja Daniels lived in an isolated cabin on the banks of Älvdalen’s river, built by Daniels’ grandparents, who are from the village and both speak fluent Elfdalian. Though Daniels was raised in Uppsala in southern Sweden, she would regularly visit her grandparents in the school holidays. “Älvdalen is part of what I call home,” she says.

There, she created her latest body of work, Elf Dalia. The photobook combines her own photographs with archival images by Tenn Lars Persson, a photographer and inventor who lived in Älvdalen’s community during the late-1800s to early-1900s.

Initially, Daniels – who studied sociology and film in London before moving to photography – approached the project from a sociological angle. “I’m not interested in sociology as a way of producing knowledge or giving straight answers,” she says, “I use photography as a tool to make connections between questions about our lives, the way with live, and society.”.

Part of the reason why Daniels moved to Älvdalen was to teach at a centre for asylum seekers, but she was also interested in how the community were trying to revive the old language in its younger population.

Up until 1950, as a way to standardise the language, it was forbidden to speak anything other than Swedish in schools across the country. Daniels’ grandfather only learned to speak Swedish when he was seven-years-old; growing up he was teased and made to feel ashamed for speaking Elfdalian. Now, in a bid to revive this repressed language, a grant has been introduced as an incentive for young people to learn the language.

“The reason that I am so interested in Elfdalian isn’t just because my grandparents speak it. It’s also a personal mystery to me,” says Daniels, “what is it that makes one language die but another prevail?”

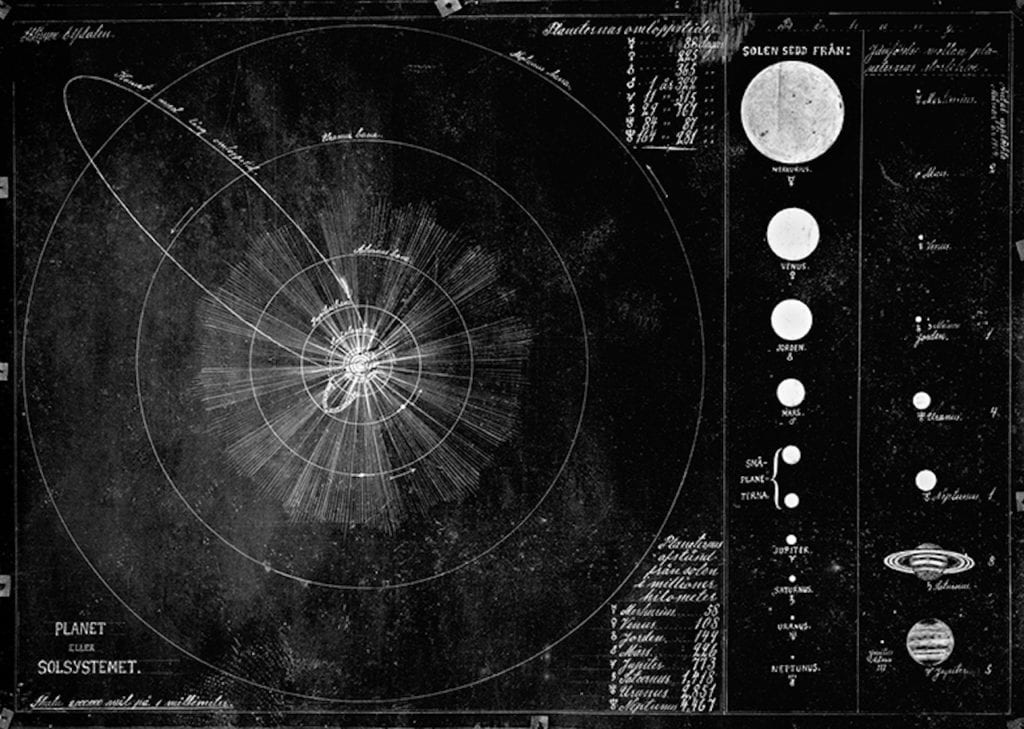

With time, Daniels’ project became more obscure. Connections were beginning to appear between Elfdalian and the region’s dark history of witchcraft and the occult. These connections were confirmed when Daniels discovered the photographic archive of Lars Persson, a local inventor and scientist who was interested in alchemy, herbalism, astronomy, and the occult.

Persson worked through the late-1800s and early-1900s, building telescopes to photograph the moon, and experimenting with glass-plate photographs by etching straight into the emulsion. He was also the founder of the Älvdalen local heritage foundation, for which he collected stories based on folklore and myths from residents of the village.

“He was a wizard of his time,” says Daniels, “there was something that he captured about Älvdalen that I had also felt. His work evokes a sense of wonder and mystery. Those elements of questioning, and the connection with the unknown, is what attracted me to making work in Älvdalen too.”

In her research, Daniels discovered links between the region’s infamous witch trials and its native language. The Christian church was built in Älvdalen in the late-1500s, but when the priest arrived from Stockholm, Sweden’s capital, he had problems communicating with his parish because he could not understand the language of the people he was preaching to.

Daniels discovered that it was also widely believed that only children could spot witches. Local historians suspect that these children, who would stand outside the church and point to those that had been with Satan, were colluding with the priests. In fact, Daniels found documents in which the priest from Älvdalen reports back to Stockholm stating “how impossible these people are”.

“For me, this is a story of resistance and strength,” she says. “The state was trying to control smaller communities by sending out priests from the capital, to make sure the people were orderly and went to church.” Rolling out a national language was also a way for the State to maintain control over isolated villages.

But, Daniels points out, Elf Dalia is not actually about Älvdalen. “It is a fictional place,” she says, a “play-on-word”. “This is not supposed to be a documentation of a language or a specific community. It is about my own personal engagement and research. It is timeless and unbound.”

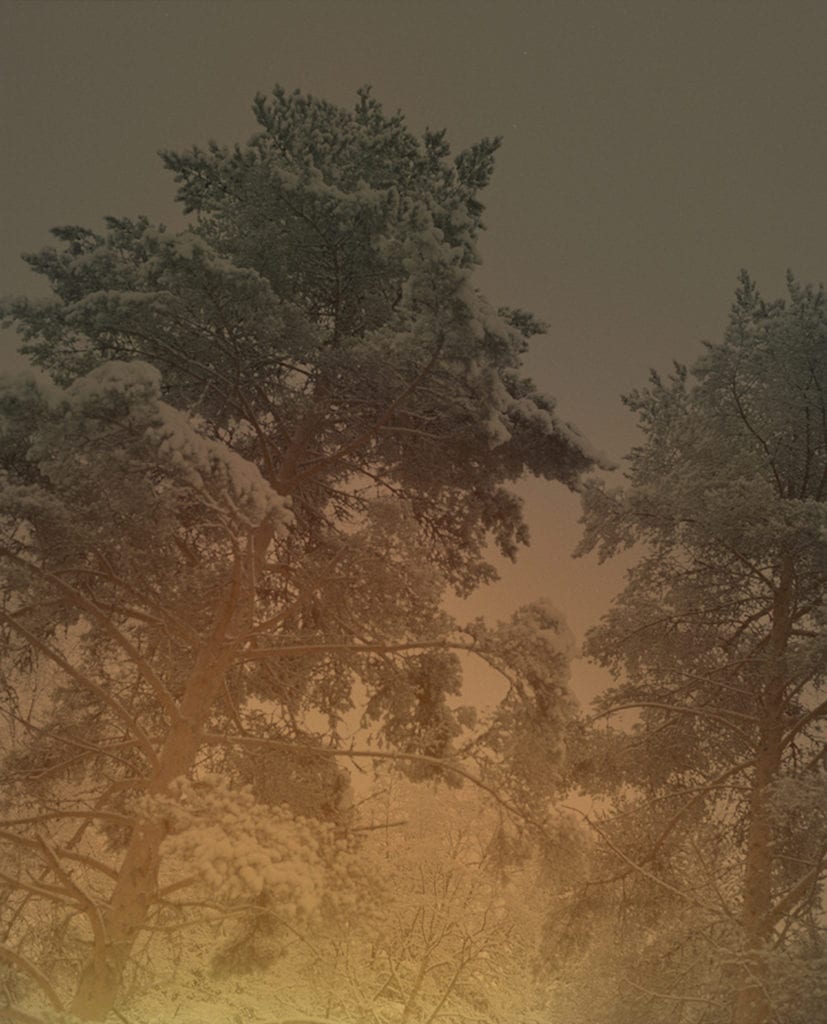

The book begins with several pages of woodland shots, guiding us into a dialogue between Daniels and Persson. Daniels cannot speak Elfdalian, so the muteness of their mutual medium is important. “Photography expresses so much, but doesn’t risk giving too much magic away.”

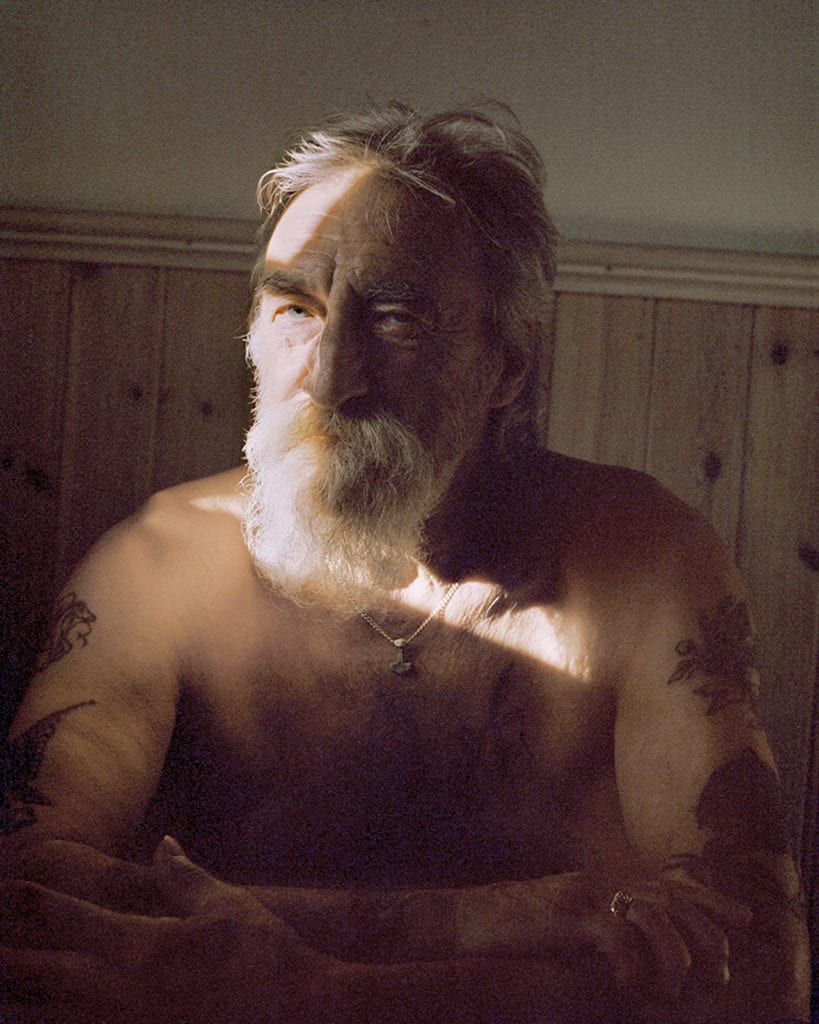

From portraits of Älvdalen’s current residents, to Persson’s sketches of astronomical observations, though they were made a century apart, performativity, darkness, and experimentation bonds the photographs together. The book includes a commissioned piece of lyrical prose by Swedish author Andrea Lundgren. Inspired by the images, its lines are short and repetitive, hypnotizing like a spell, intended to embody the voice of the forest.

In her own photographs, Daniels plays with light, over and under-exposing her film to “reveal them to the elements,” and to “draw a parallel between the fragility of the actual negative and a language that is at the brink of disappearing.”

Still, although Elf Dalia is based on these parallels and connections that are drawn between the mysteries that shroud the region, it does not offer any answers. “Because I wasn’t looking for them,” says Daniels. “I’m not trying to solve a problem here, I’m trying to engage with a feeling.” Afterall, the thrill of a mystery is sometimes more exciting than finding the answer.

Elf Dalia by Maja Daniels is published by MACK, available to purchase for £30.

www.majadaniels.com

www.mackbooks.co.uk