Katrin Koenning’s documentary projects are fluid in process and poetic in aesthetic. She often works on several series at once, and, similar to how she found her way into photography, lets intuition and circumstance guide her practice.

Raised in Bochum, Germany, Koenning moved to Australiain 2003, completing a BA in Photography in Brisbane before relocating to Melbourne, where she now lives, works, and teaches. Koenning has won multiple awards, including Australian Photobook of the Year and the Daylight Photo Award, as well as receiving numerous nominations for prestigious prizes such as MACK’s First Book Award, and more recently the Greenpeace Photography Award.

Many of Koenning’s projects –Lake Mountain and The Crossing – are driven by the anger she feels towards governmental policies that prioritise short-term profits over sustainable decisions for the environment and future generations. One of her most recent bodies of work, Swell, seeks to highlight this current state of urgency, not through the expected tropes of disaster imagery, but by focusing on a number of small ecosystems in Australia.

As Swell goes on show at Monash Gallery of Art in Melbourne, BJP-online speaks to Koenning sabout what drives her photography, the importance of letting go, and her advice for young photographers.

–

BJP-online: How did you get into photography?

Katrin Koenning: Photography rushed into my life with great force and tenderness when my oldest friend Tobias, who I’d grown up with, died in a plane crash above Iceland just weeks after we graduated from high school in 1998. He wanted to be a pilot, but his passion was photography. Inheriting his old Minolta, I left for Iceland to be closer to the loss. I worked there through the depths of winter, for three months, in remote greenhouses. All the pictures came out blank because I had no idea what I was doing, but the very act of walking in snow,and the silence with the camera in my hand or against my body, mostly in the night, made me feel okay.

Losing Tobias taught me to attribute everything an urgency; that things are always transitory, never permanent. It made everything matter. It also positioned photography as something that has to be intimately connected to who you are.

Back in Germany I pursued broadcast and written journalism for a bit, and interned for the photo department at Zeche Zollern, an industrial museum in a former coal mine in Dortmund, where I learned how to use a darkroom. I was given my own key and spent entire weekends in there, on my own, falling in love.

Swell is an ongoing project – what it is about and why did you start it?

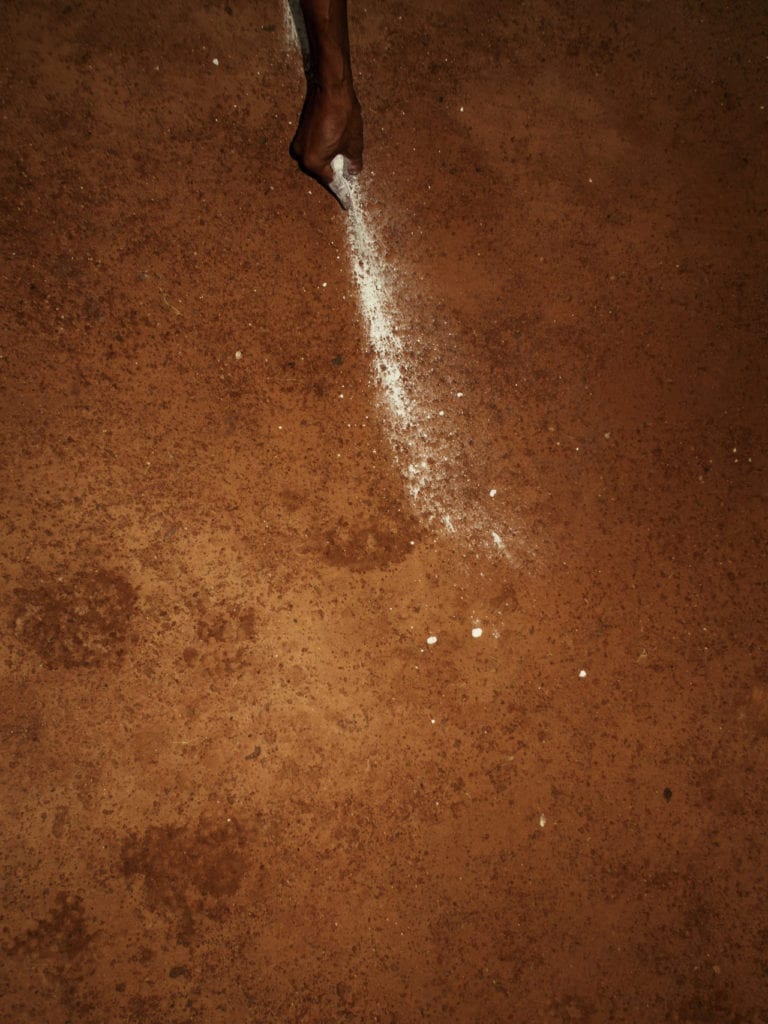

In 2015, communities and organisations across Australia were struggling to put a stop to the country’s largest coal project — Adani’s Carmichael Coal Mine – and the government responded by limiting conservational philanthropy and even considered repealing laws in order to restrict green activism. Today, this political climate of vested interest continues and Australia is always at risk of losing further precious eco-systems, all in the name of ‘economic growth’.

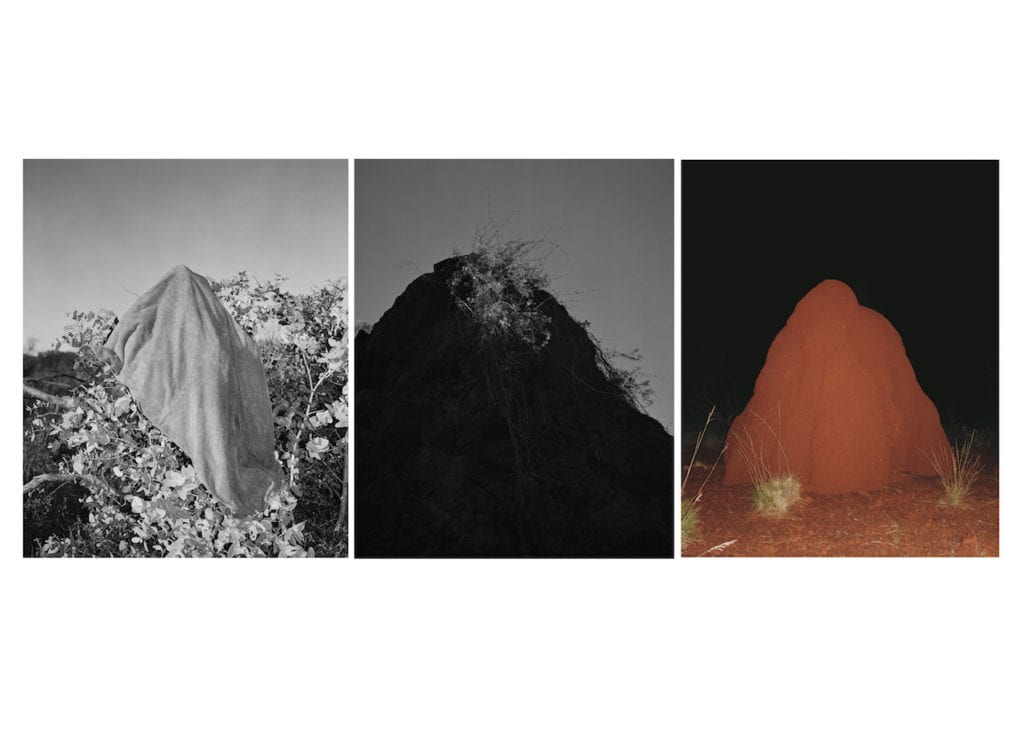

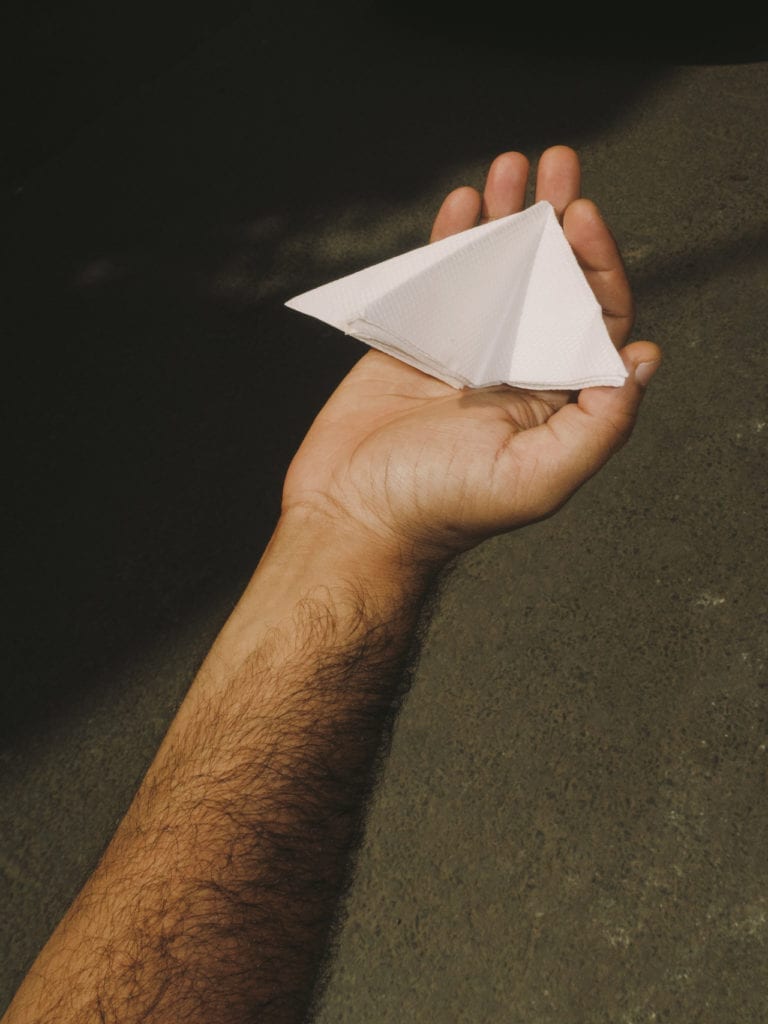

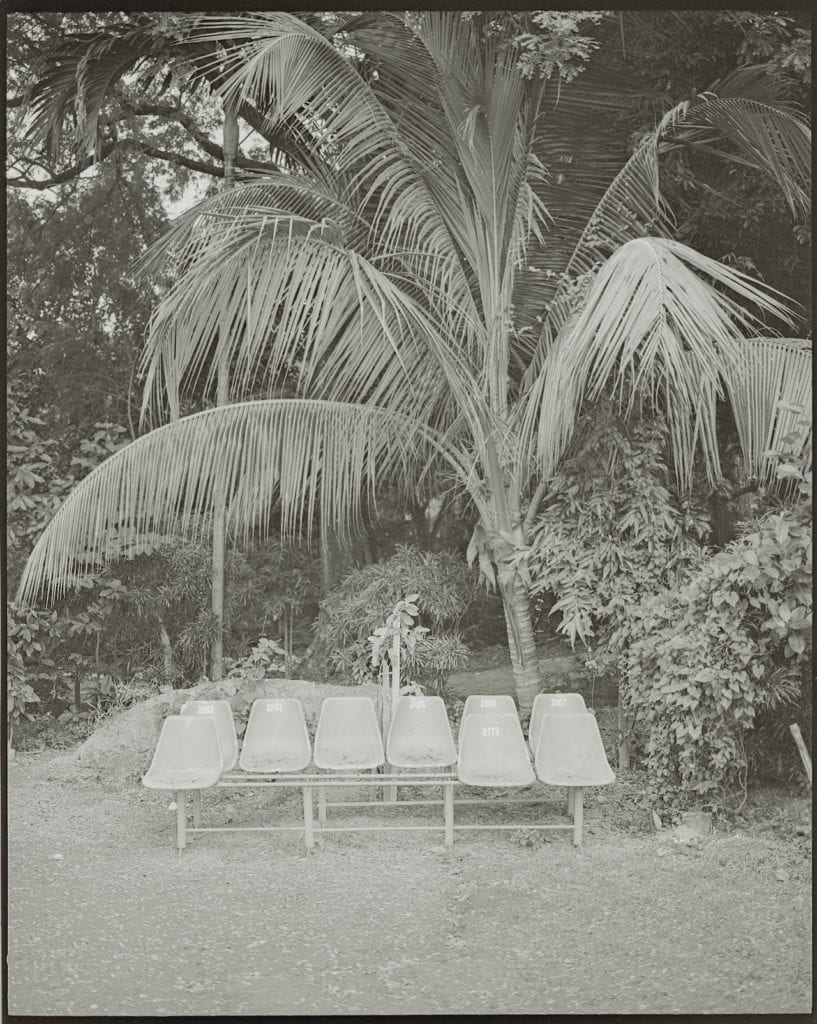

Swell is born out of anger at policies that elevate short-term profit above the need to make sustainable decisions and safeguard our future. Avoiding expected tropes of disaster-capitalism, and rather focusing on a number of mini-ecologies across Australia, the work seeks to present counter-narratives and positive ecological imaginaries to highlight our state of collective urgency. It creates a space in which things are connected, rather than apart. Swell is a work in progress; a personal narrative about nature hanging in the balance.

It is interesting how you overlap photographs. Are these pairings intentional or intuitive?

They’re intentional – they’re meant to extend the reading of the work and enter into an intimate dialogue within certain clusters of images. The work is about interconnectivity, this idea that things are connected and never in isolation. Many of the pairings suggest this, be that through content or through visual or aesthetic elements.

Your visual style is quite distinctive – how did you develop this?

I’m not sure if I have a good answer to this question – I don’t think I set out to develop a certain style. Perhaps the way a language falls is with intuition. You always try to find the right way to approach something and to translate it as best as you can, to do the story or idea justice. With time, intuition becomes a crucial part of one’s visual sensibility.

Experimenting is crucial to photographic development. Through letting go, you stumble on new ideas, or things that trip you up, and in that small peripheral moment, when you trip up and you’re mid-air, something unforeseen can emerge, and from this emergence can come growth.

You can also develop a language by trial and error. You make many shit pictures, and some good ones too, and you sit down with them and see what’s going on and how you got there and what went wrong and why. Most importantly, you observe how they may function as a group. It takes a kind of obsession too; you won’t’ be able to build anything by sitting idly on your bum. Hybridity is important to my work and method – again this idea that nothing is finite but that everything is always in motion. Everything has fluidity and is connected rather than apart.

Who, or what, are your artistic inspirations?

In photography, some of my very first loves were Nan Goldin, Mary-Ellen Mark, Koudelka, Sternfeld, Trent Parke, Robert Frank. The first photobook I ever bought was Storylines by Frank.

My grandmother Marga was my earliest inspiration beyond doubt; she was a painter. I’d watch her for hours, day in day out, making the canvas into her world. She taught me so many things, and her worlds were always a little bit strange. She was magic to me. The other early inspiration came from my grandfather, who had an art gallery. I remember so many nights there, as a young girl at the openings, surrounded by paintings and sculptures, in total wonder.

But mostly inspiration comes from life; from lived experience and emotional truths. It also comes while walking, or from a stone on the street, my friends, some bizarre newspaper headline, a scent, or words you hear on a tram. And then of course there are music, books, and films.

Many of your projects seem to shift between reality and fiction. Where does this interest come from?

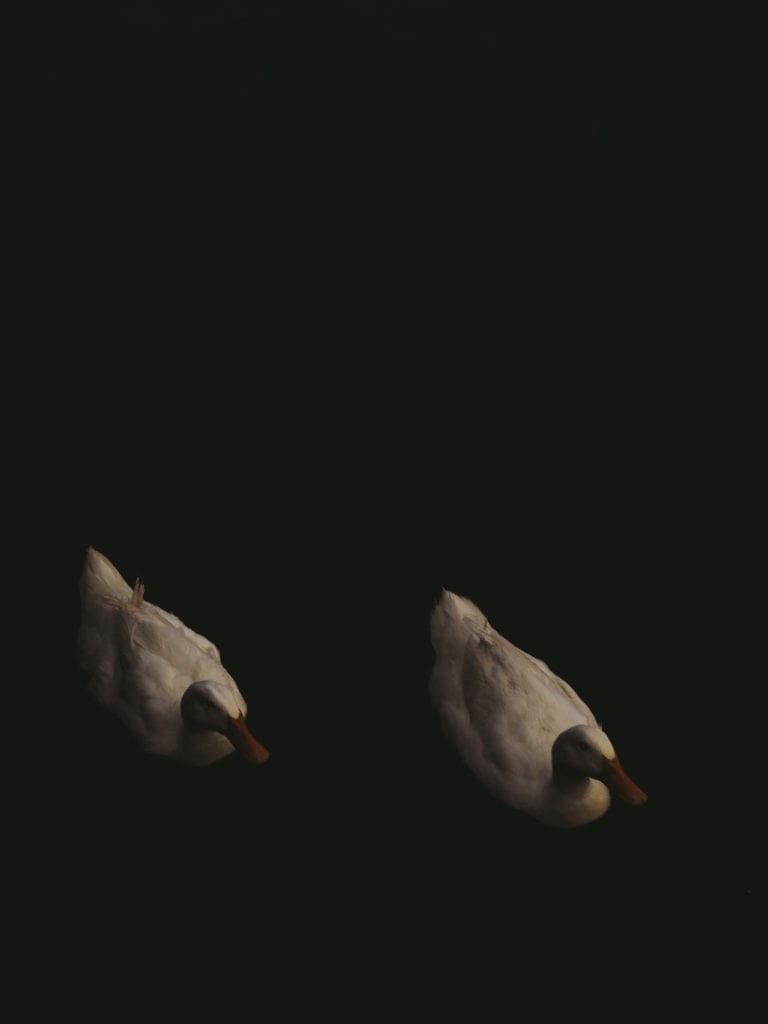

My method is very much a documentary – with poetic intentions. All my works are made in and with the world. For example, a light can hit a surface, let’s say a piece of rubbish on grass. If I position myself in a certain way to it, cutting out the glare of the light, the object is what it is; a piece of rubbish. If I position myself to it so that the light bounces into my teeny little camera and freaks it right out, the rubbish no longer looks like itself. It’s now a bundle of glow in the middle of grass. And while it appears as something different or abstract or fictitious, what it really is remains the same; a piece of rubbish met by the sun. It’s super real but it looks surreal.

This is the potency of shifting ways of seeing. I’m not really interested in talking about a fictive world – I’m interested in reality, and the fact that reality is so very strange and interesting and has a million different identities and appearances at any given point in time.

How do you make ends meet as a photographer, do you work on commissions to support your personal work?

The money thing is hard, you have to do lots of different things and be creative with it. I do a lot of teaching which I love so I feel very lucky in that way. And then my work is available as limited-edition prints, and of course I do commissions and assignments and I work with other artists to represent them and their practice, mostly musicians. I enjoy working to a brief because it is about problem-solving; you have to think on your feet, be quick, people-manage, do the maths, know your light, figure stuff out. It’s a space where a lot of energy floats around and I like that.

One of my dearest friends and I used to shoot weddings together while we were studying. We always felt that it was incredible access to someone’s life, culture and intimacies for a day. On a wedding day all the guards are down, you get to witness people feeling things. Doing it together was great because we always had each other, and if something went wrong for one of us, the other had it covered. We also learned a lot from seeing how we each saw separately, and together. I think students should go and shoot all the jobs they can get and not be snobby about doing certain events. These things are brilliant exercise and they only make you grow, improve, and see more profoundly.

What is the one piece of advice you would give to a young photographer?

Help others, be kind and rigorous, and mostly – burn.

–

Swell by Katrin Koenning will be on show at the Monash Gallery of Art in Melbourne, Australia until 12 May. A selection from her latest bodies of work will be on show at Peckham24 in London, from 17-19 May.

www.katrinkoenning.com

www.peckham24.com

www.mga.org.au