If you wanted to become a professional photographer in the Soviet Union, says Victor Kochetov, you only had two options. Either you could work at an atelier producing pictures for books or postcards, or you could work for the press – and both meant conforming to the ideological pressure of the state. Kochetov chose the first option, and through the 1960s he worked as a commercial photographer in Kharkiv, Ukraine, photographing events such as weddings and funerals, and providing images for books on travel.

“In the USSR, there was no such term as ‘art photography’, at least not in Kharkiv,” he says. “There were some photography clubs at factories or big institutions, but it was mostly typical amateur photography. Everyone was just taking pictures of their children, wives, cats and sunsets.”

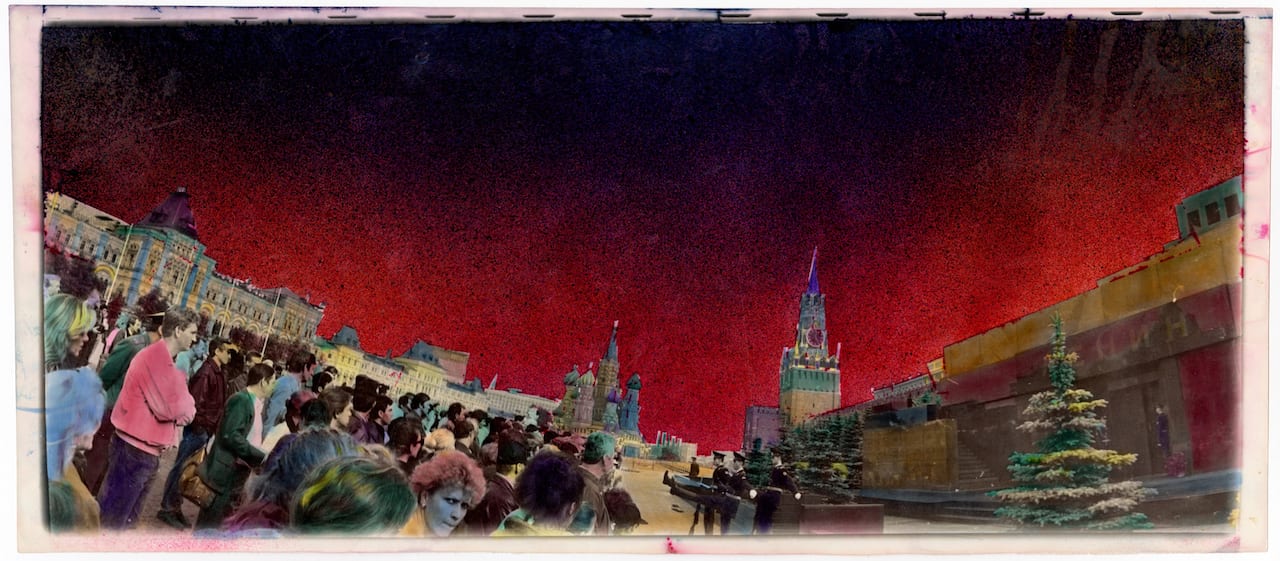

But Kharkiv has an interesting photographic history. In the 1970s it was the birthplace of The Vremya (“Time”) Group, which was set up by Evegniy Pavlov, Yuriy Rupin and Boris Mikhailov, and included members such as Oleh Malevaniy, Oleksandr Suprun, Oleksandr Sitnychenko, Gennadiy Tubalev, and Anatoliy Makiyenko. These artists rejected the aesthetic criteria imposed by the state, which would usually have meant that they were censored and persecuted. But for 15 Soviet years, The Vremya Group managed to secretly create, exhibit, and preserve their work in Kharkiv.

“They were part of a very small circle that affected everyone who got in touch with it,” says Kochetov, who met Boris Mikhailov, Jury Rupin and Olexander Suprun in the mid-1970s. He says he owes much of his career to these artists, because they encouraged him to make fine art and make pictures for himself. “Mikhailov’s style of shooting – presenting two photographs on one sheet using writing on top – it was something that turned our work over,” he says. “It was unique. My discussions with Rupin and Mikhailov and their positive response to our work was the only stimulation and purpose for us to continue along this artistic route.”

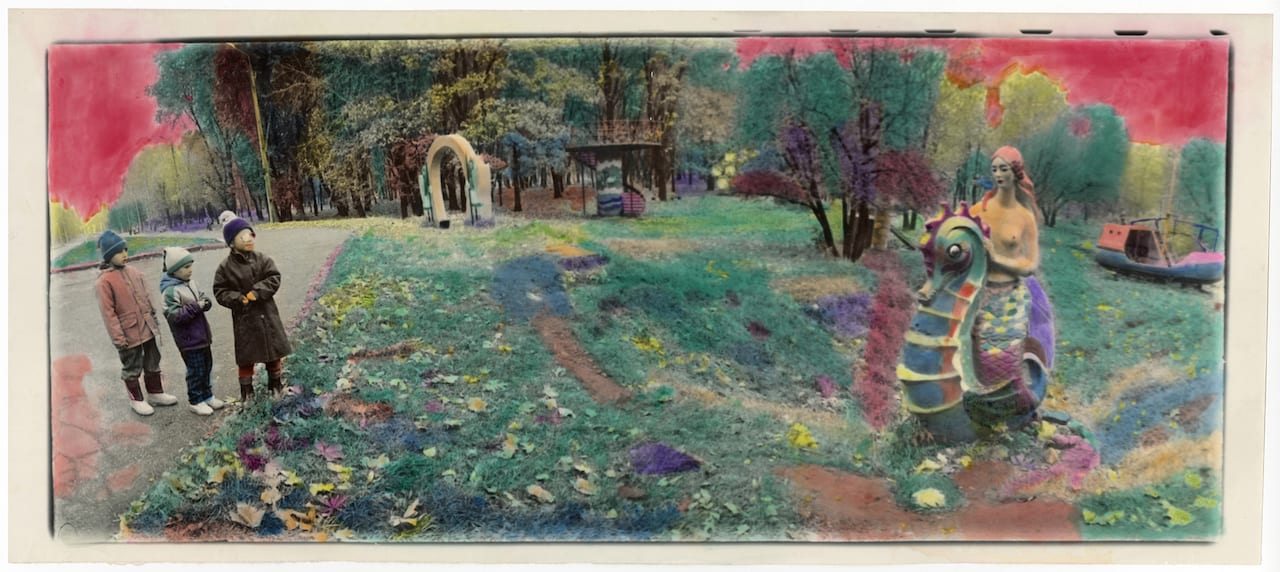

On 26 May 1972, when Victor was 25 years old, his son Sergey was born. “Our collaboration began right after he started to sit on the potty,” says Kochetov. “He became my best model.” When Sergey was old enough to take pictures himself, they started to work collaboratively, and later helped each other by filling in for their odd jobs. Now their collaborative book KOCHETOV has been published by MOKSOP (Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography), gathering together images they made from 1970 right up to the year 2000.

The publication is part of a project launched by MOKSOP to collect, exhibit and publish work by established and upcoming Ukrainian photographers – other upcoming releases include a book by Jury Rupin, and another by Sergey Solonsky, who worked with Mikhailov as part of the socially-oriented Fast Reaction Group in the 1990s. Later this year MOKSOP plans to publish photobooks by two younger Ukrainian artists – Vladyslav Krasnoshchok’s documentation of life in an emergency hospital in Kharkiv, and Sergey Melnitchenko’s project on young bodybuilders from southern Ukraine.

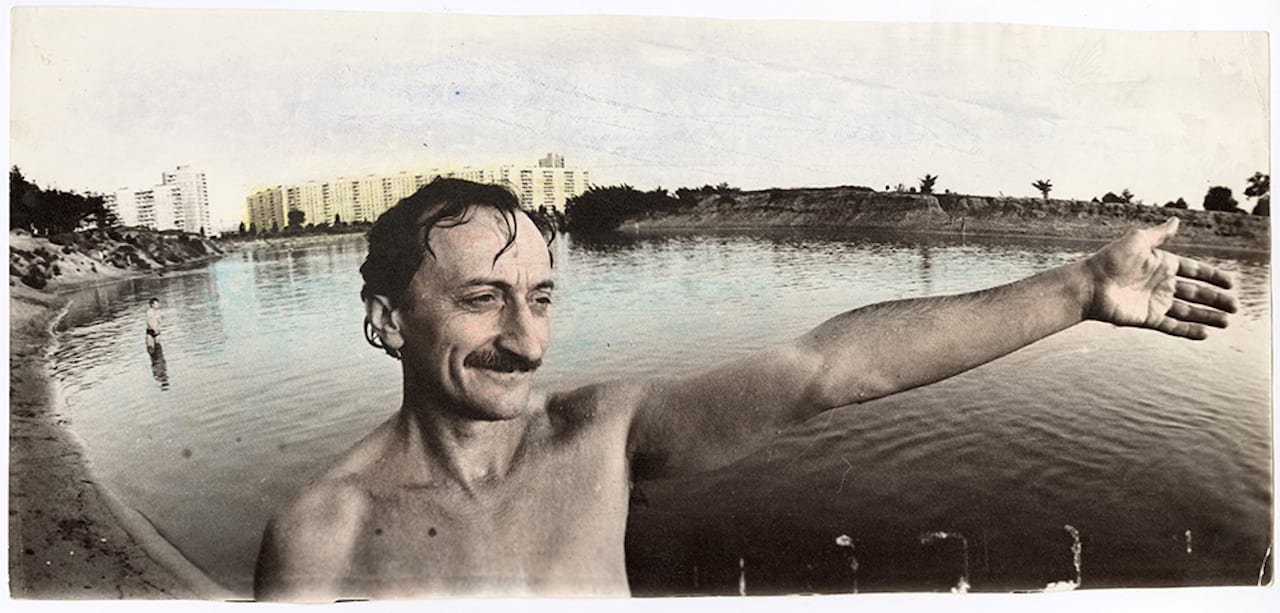

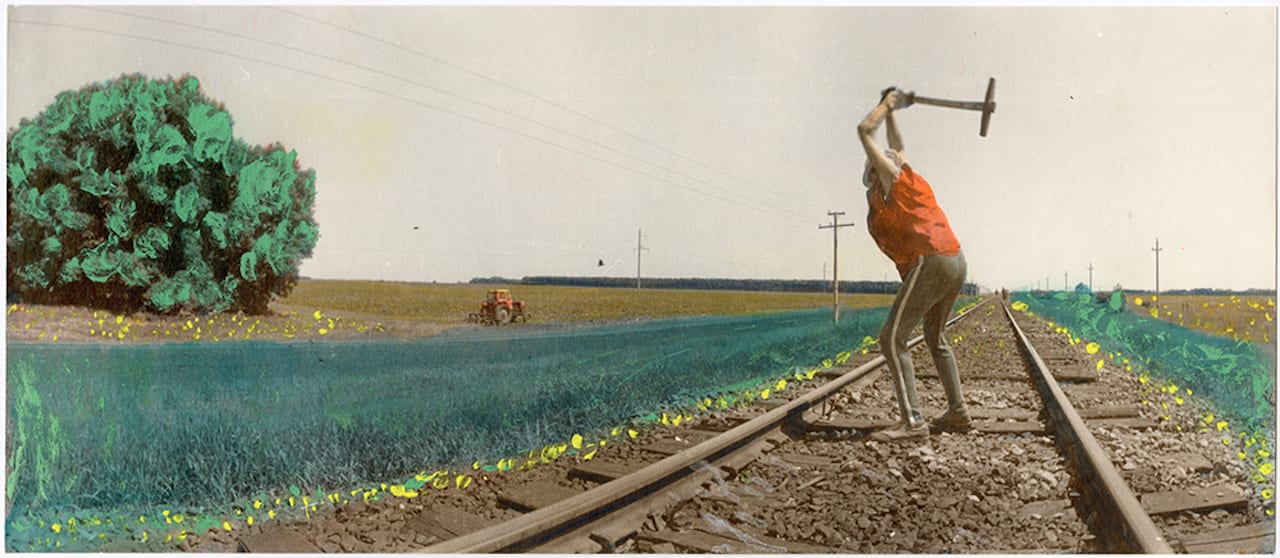

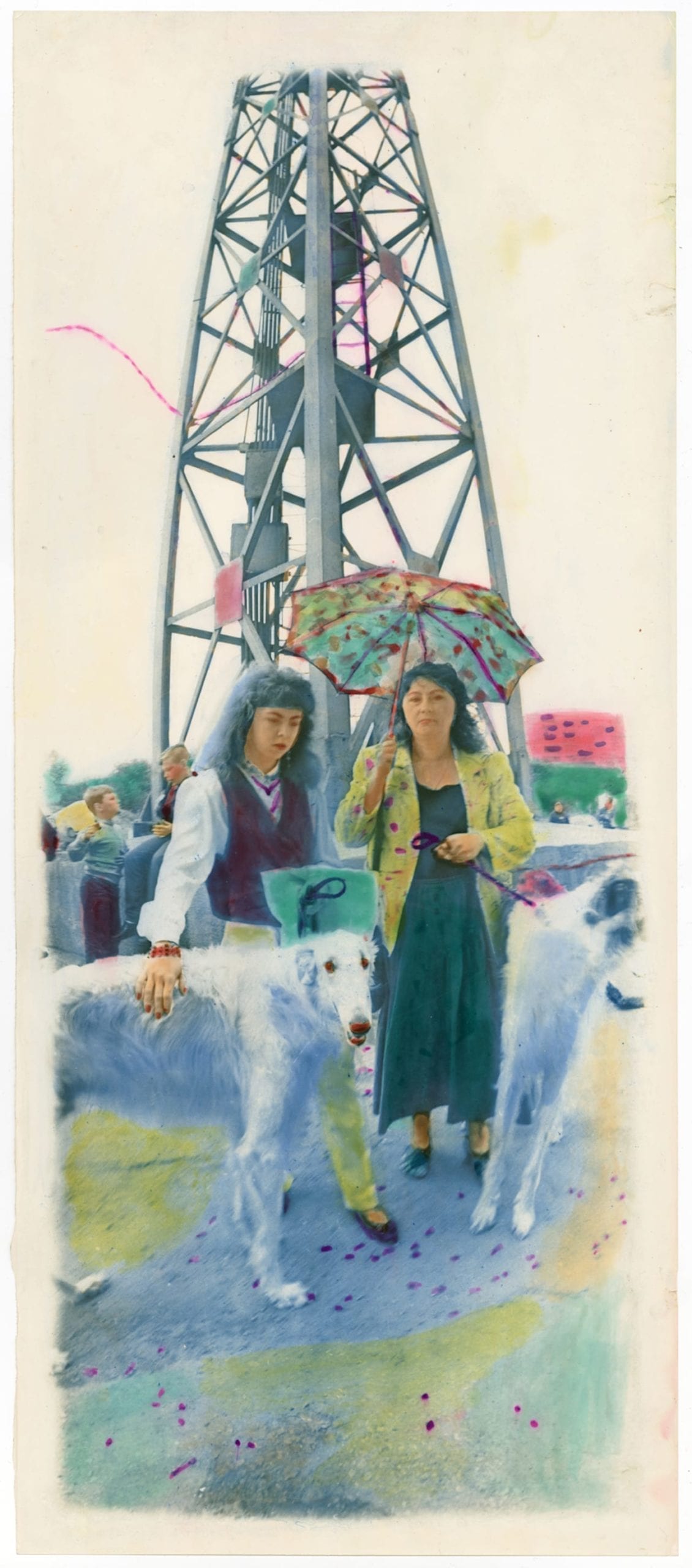

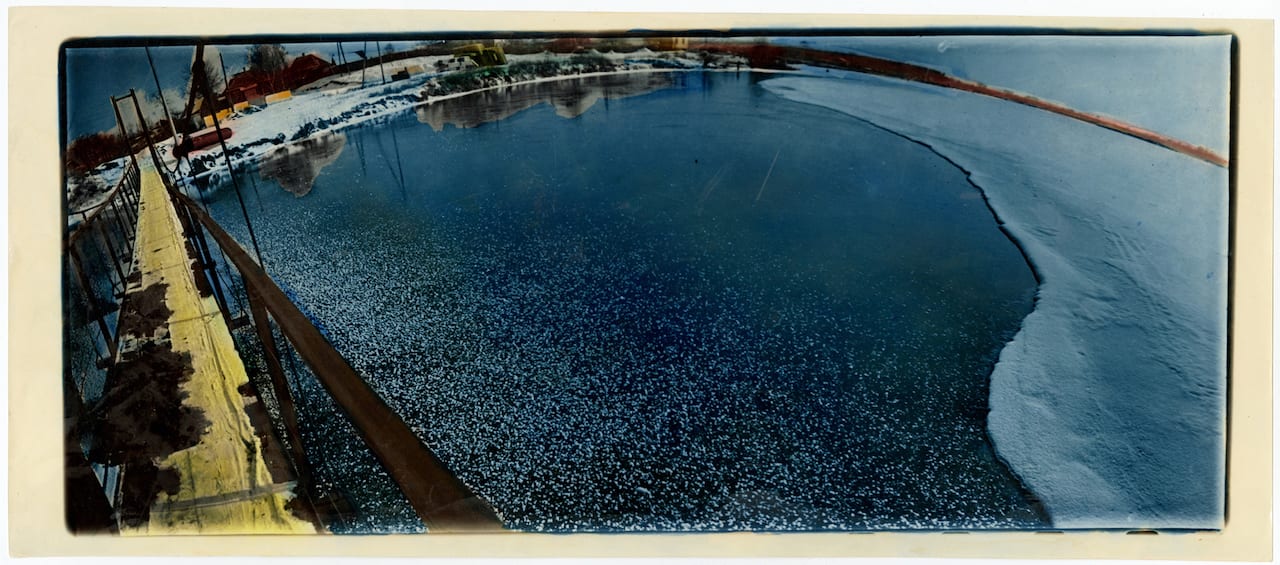

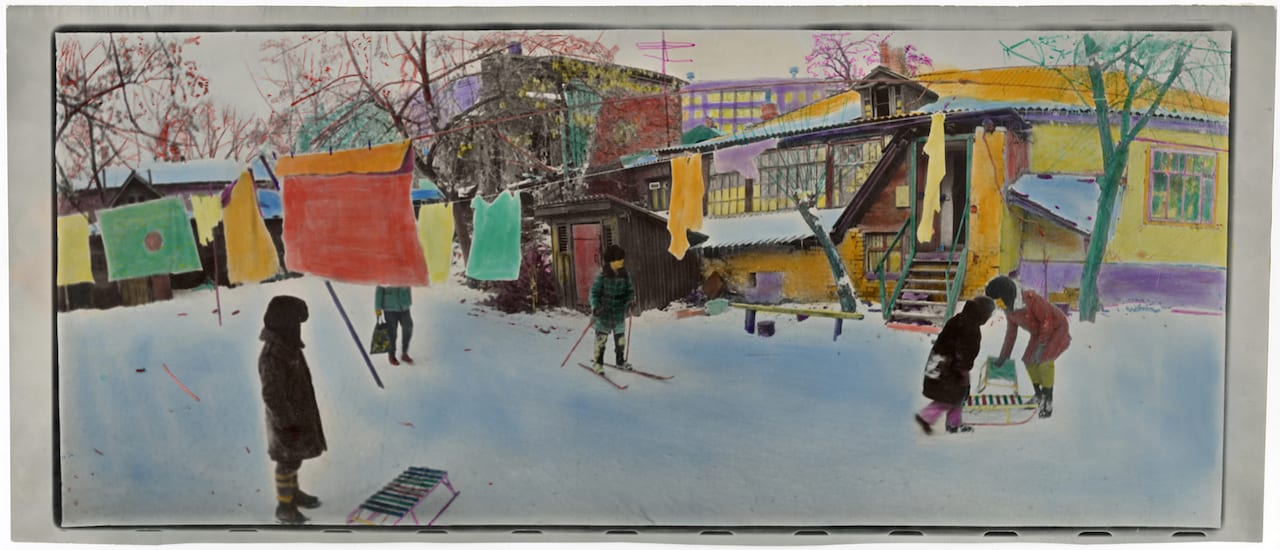

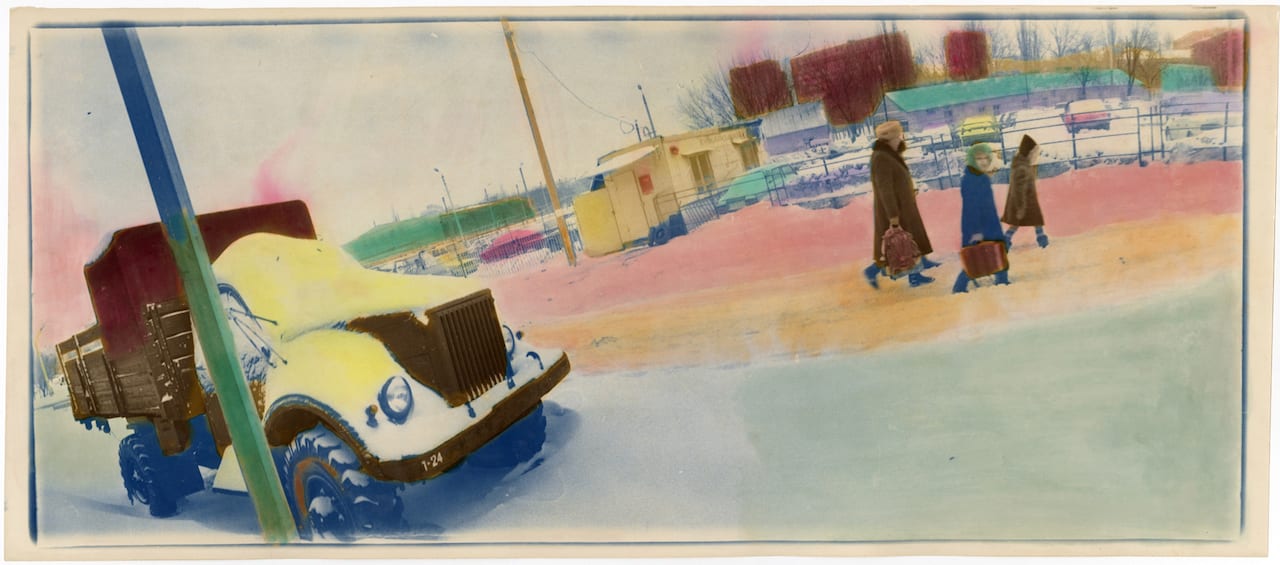

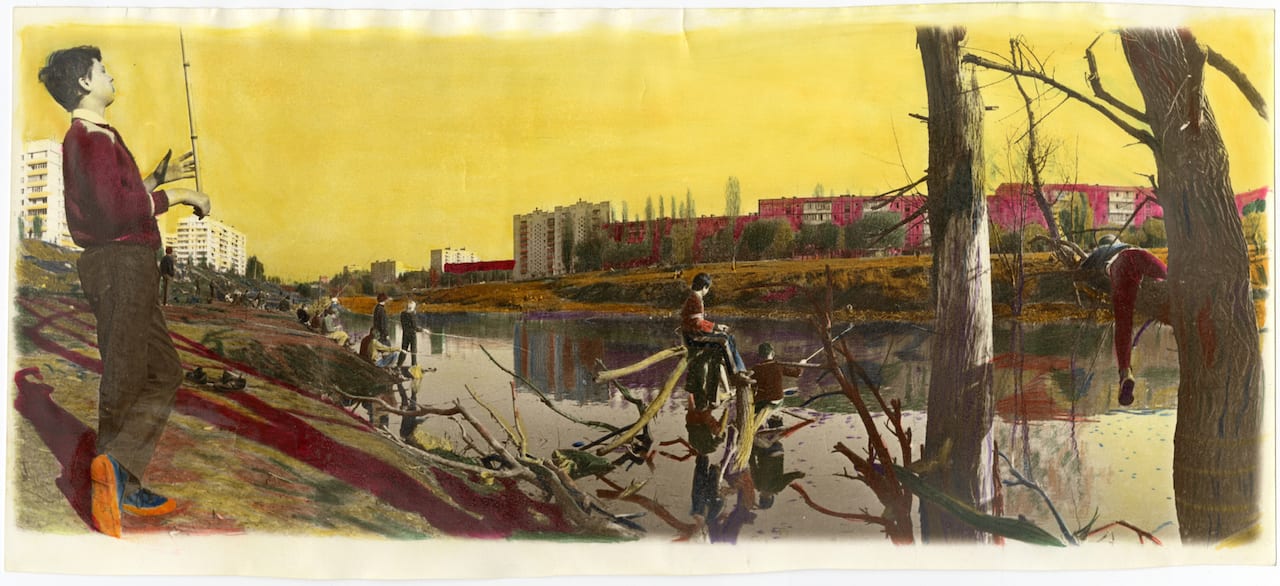

But MOKSOP chose to make KOCHETOV its first publication because its hand-tinted images are “so visually strong that it is able to amuse even a demanding contemporary viewer” – and, adds Sergiy Lebedynskyy, founder of MOKSOP, it represents a photographic history that is largely unknown to the broad public. Victor says there was no real reason why he and Sergey started to paint their photographs, or work with a panoramic camera, other that it looked more interesting. But in doing so, they were inspired by Boris Mikhailov’s hand-coloured series from the late 1970s, Luriki.

Luriki was an underground method of hand-colouring black-and-white photographs which, in an interview published in Beyond Memory: Soviet Nonconformist Photography and Photo-related Works of Art in 2004, Mikhailov referred to as “Eastern idiocy,” and the “backwardness of Soviet Technology” – explaining that it was used only because he, and others, couldn’t get hold of colour film. But, as Mikhailov also later points out, the technique revealed an irony and humour in the ordinary, creating images that “made people smile”. “The main point of Luriki was ‘making the beautiful even more beautiful’ with the help of old-fashioned, lagging technology,” he said.

Officially the hand-coloured images were considered bad taste and kitsch, and most exhibitions during Soviet times didn’t accept them. Even so, it was popular. “It was of high demand,” says Kochetov, “which is why Kharkiv became the centre of production of luriki for the whole of the USSR in the Brezhnev times [1964-1982].

“There was no particular idea or vision behind it, we just worked on the picture until we liked the result,” he adds. “But one could analyse particular images, and the usage of certain colours. If pink is used on ‘masculine’ images – and most Soviet propaganda images do look masculine – it may provoke an opposite effect. Or blue, the colour of dead body, is very heavy and disturbing.”

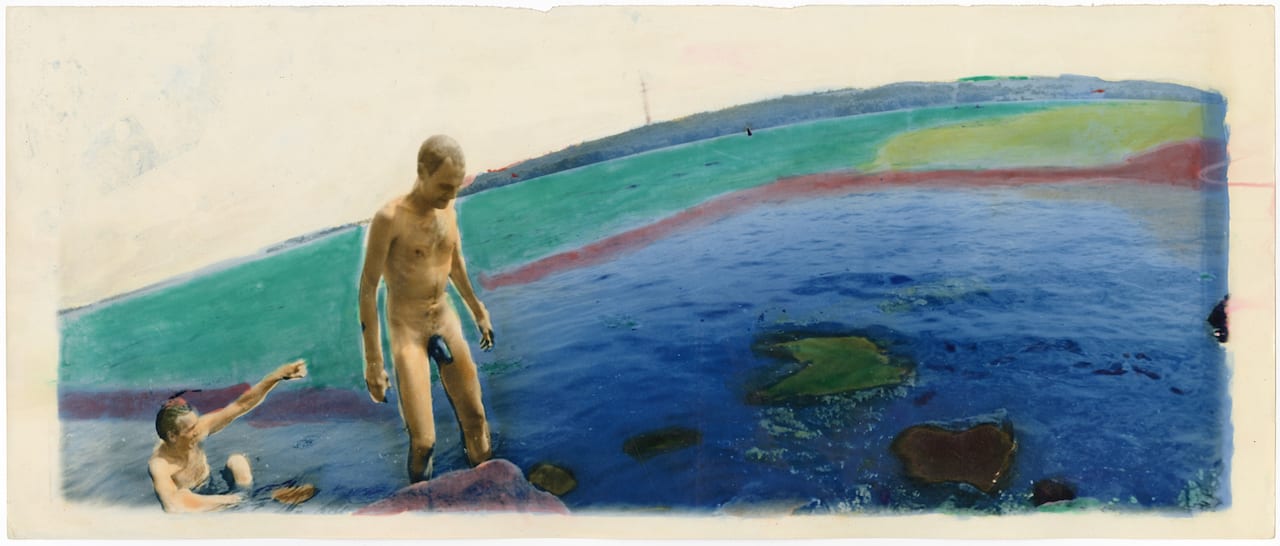

The publication KOCHETOV contains a lot of nudity, something which was also not encouraged by the Soviets. Nude photography and references to sex in general were taboo, says Kochetov, and could not be shown in Soviet times – any images including nudity, including lightly pornographic shots, were confiscated by authorities and destroyed. “The ideological pressure was pushing all photographers to self-censorship, nobody would try to show such pictures in public,” he says. “Every single exhibition or photography show was checked by the state prior to it’s opening.”

This censorship could be what led to the popular belief that “there is no sex in the USSR,” a phrase blurted out by a Russian actress during a live TV show aired in America. But though sex wasn’t discussed it certainly happened – Kochetov recalls having unlimited access to condoms at state pharmacies, for example, sold for 4 kopeks (around 0.05 pence) a pop. So while the images in KOCHETOV were difficult to show at the time, and may appear surreal at first glance now, for Kochetov, they’re mostly a record of everyday life. “All of these photographs were included because they were part of our life,” he says. “We are glad to finally show them in a book.”

KOCHETOV is published by MOKSOP, priced €50 www.moksop.org/en/product/kochetov/