On 20 April 2011, Guy Martin was seriously injured in a mortar attack while covering the conflict in Libya. Two fellow photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, were killed, and it was a year before Martin could walk again. It was another six months before he wanted to take pictures again. By the end of 2012 he had moved to Istanbul to start a new photographic project but his experience had fundamentally changed him. Though he had been enjoying a burgeoning career in photojournalism, shooting conflict in Egypt, Libya, Ramallah and Georgia for The Wall Street Journal, Time, The Guardian, The Sunday Times, Der Speigel and many more, he decided to take a step back.

“To not learn from that event in April 2011, I couldn’t do that to myself,” he says. “I couldn’t justify it to my family, I couldn’t be put in that same situation again. The starting point was to take control of my photography, to use my photography instead of letting it use me. I come back to this thought again and again – until that point my relationship with photography was wrong. I think perhaps photography was using me, and I thought for a long time about how that perhaps applies to many young men and women…And I get very angry, because I had to learn the hard way.”

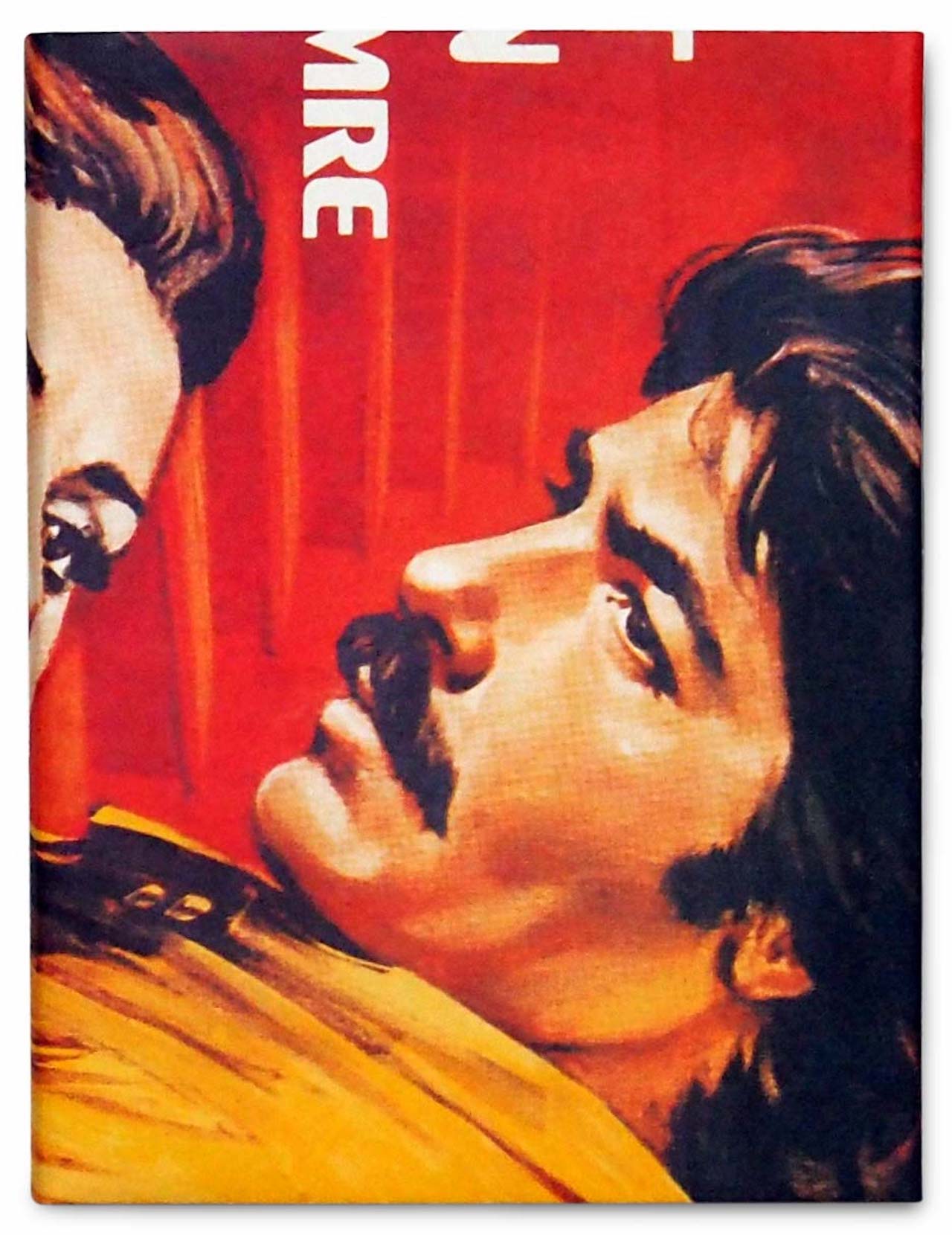

Instead he started to investigate Turkish soap operas, lavish productions exported throughout the Arab-speaking world. Turkey in 2012 was “this model of democracy and secular leadership in a Muslim world on fire”, he says, at the peak of its accession talks with the European Union, and highly influential in the Arab world; for Martin, the soaps reflected some of its power and glamour.

“Finding something that explained Turkey so well – or the way it exported its image – was amazing,” he says. “Turkey was at this wonderful, colourful peak. And the viewing figures for the soap operas are insane. They’re the most-watched soaps in the world, bigger even than the Mexican and Brazilian telenovelas because the Muslim population from Bosnia to Indonesia is massive.”

Put in touch with a soap director by a PhD researcher, he was given free rein on set, allowed to stay all day and shoot exactly what he pleased. “It was great, I wanted to leave the house in the morning,” he says. “I could go onto a set, shoot all day and come back and not be afraid to fail, not have to impress any picture editors or anything like that. It was purely for me….I don’t think I’ve ever had that much creative freedom.”

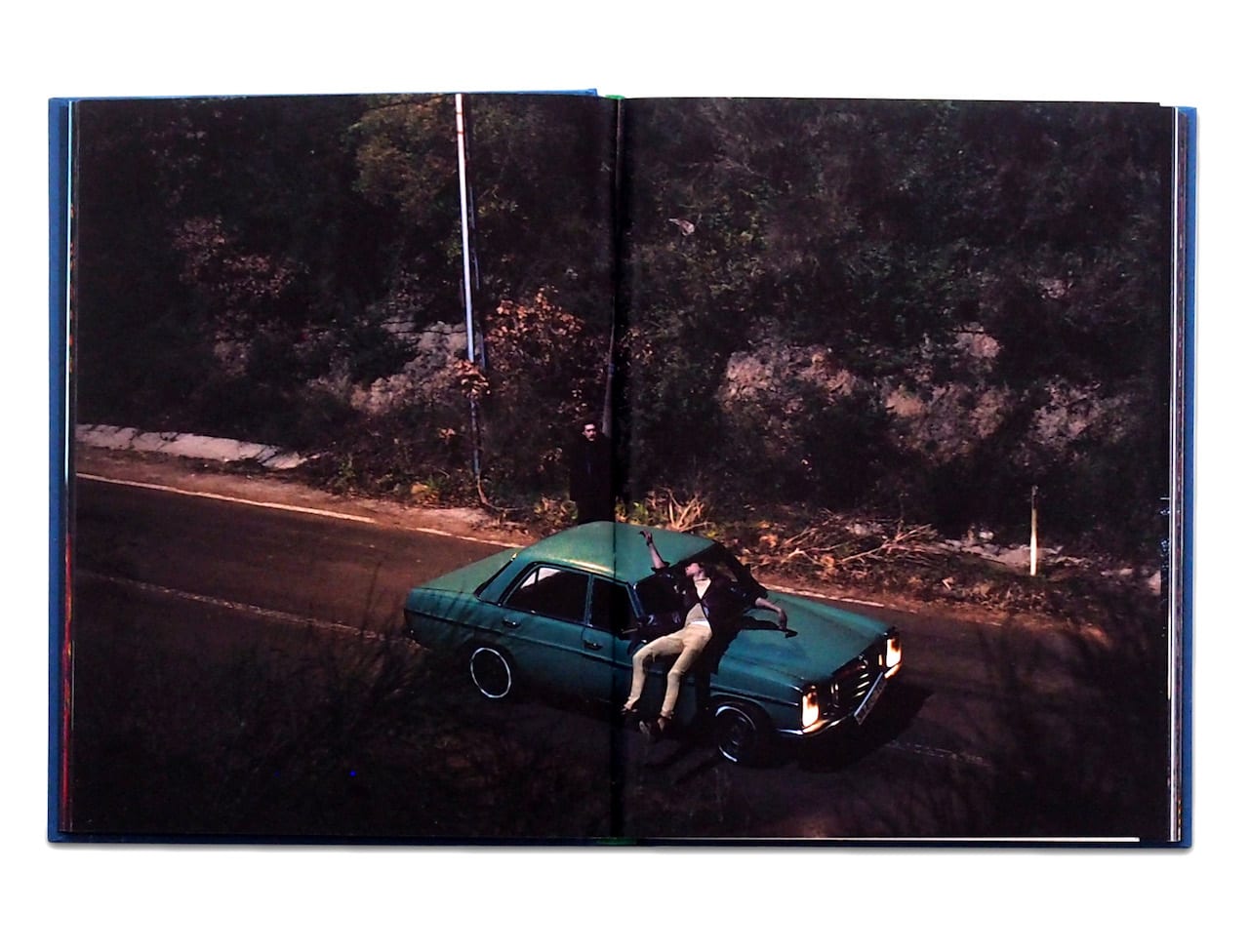

Still, as Martin points out, he’s always had his own style. Even when covering the social unrest and conflict he sought out the quiet moments, and before long in Turkey, he found himself setting parameters. First, he decided not to show cameras or wires, or any other indication that what he was shooting was a fiction. And second, he decided to shoot two or three seconds before the director shouted “Action!”, and after he or she shouted “Cut!”

“So in my own way, I was exploring that grey area between documentary and fiction,” he says. “They weren’t acting, they were out of character, so they were in a genuine moment – and I was like ‘OK! I’m not asking you to wait here, I’m not asking you for a portrait’. It was my way of shooting documentary photography.”

Time went on and Martin says he would have been perfectly happy with this story, which would have been “nice and hopefully well-received”. But then fate and events intervened. On 28 May 2013 protests broke out in Taksim Gezi Park, initially against an urban development plan for the park but soon expanding to include encroachments on secularism, police brutality, a wave of privatisations, and protests for freedom of the press and freedom of expression and assembly.

Martin couldn’t believe it, and initially didn’t want to get involved. Eventually curiosity won out but, keen to avoid being sucked back into hard news, he started shooting in a radically different way. “I was adding multiple flash guns to my camera,” he says. “It felt bizarre, this kind of contraption, but I knew I was not going to photograph in the same way as I had done before. Maybe subliminally I was inspired by all the soap opera stuff – being in control of the light, working slowly. I guess I was photographing as if I was a director.”

He also sought out a certain type of person because, by now familiar with Turkey and Istanbul, he knew the protesters were a very particular type. “They were overwhelmingly middle-class, secular, wealthy Western Istabulis – these beautiful girls protesting, wearing nail varnish, taking selfies, doing a perfectly good job of getting the news out themselves,” he said.

“Seeing that made me question my role again, made me think I couldn’t make this look like all the stereotypes of protests in the Middle East…I didn’t want to make these protesters look like every other protestor, I wanted to be absolutely specific about the time and the place and the type of people that were doing that,” he continues. “It was important because I was acknowledging my role and acknowledging the importance of their role in the revolution, the use of the screen and the phone.”

In fact some of the protesters were even actors and actresses he recognised from the soaps – and by September, when the protests died down, he had started to notice uncanny visual correspondences between the two stories too. Urged on by his fellow photographers Anastasia Taylor-Lind and Ivor Prickett – friends from the documentary photography course at the University of Newport, which he graduated in 2006 – he decided to combine them.

“They said to me ‘That picture of the guy on the grass looks so similar to that soap actress, you have to put them together’,” he says. “There wasn’t any massive grand scheme at that stage, other than to be a little bit weirded out and shocked that images that I’d taken on set were so similar to images that I’d taken during a time of violent social unrest. Because it wasn’t intentional – I didn’t conceptualise it in that way, I just reacted to these things – when I put them together I was shocked.”

So began The Parallel State, an epic four-year project including both documentary shots from the street and photographs taken on-set. A picture of Turkish life including its dreams as well as its realities, it shows how those fantasies are inspired by real events – and how in turn, they influence them. It shows, in fact “that grey area between documentary and fiction” that Martin originally sought out on set.

The title comes from a term coined by American historian Robert Paxton to describe organisations which exercise soft power, which promote the prevailing political and social ideology. It is also used by Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, to mean something like the opposite, however – the power of those acting against him and his rule. Either way, it speaks of an influence, of the power that happens before force.

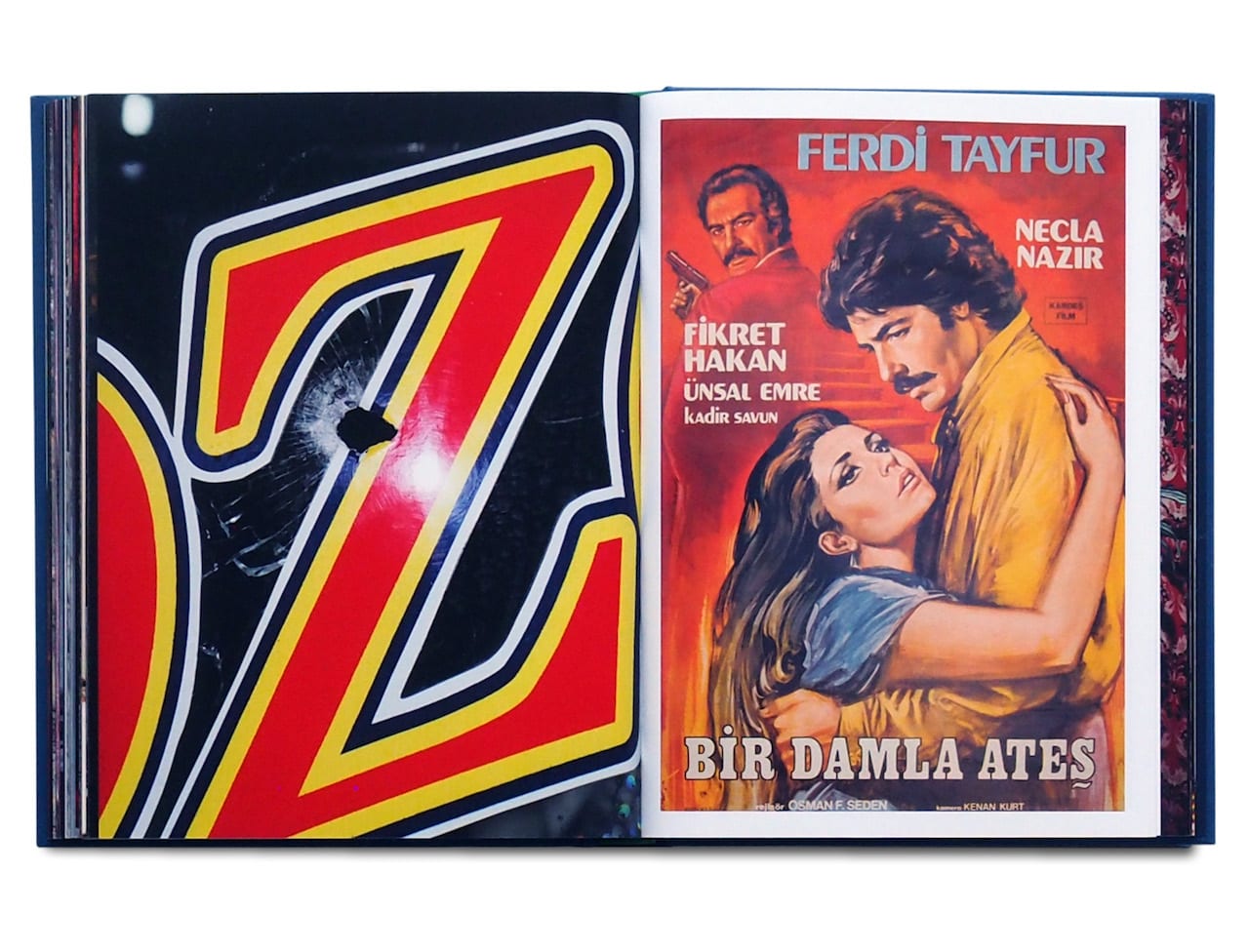

Many of the soap opera storylines involve love, “a poor village girl who moves to Istanbul and falls in love with this white Turk, Western-looking, apparently the ultimate man to fall in love with because he’s wealthy and looks European” but others deal with darker topics – secret plots in the Turkish military police, plans to execute the President. And if some of them seem hammy or far-fetched, by the end of 2016 all too many had come true.

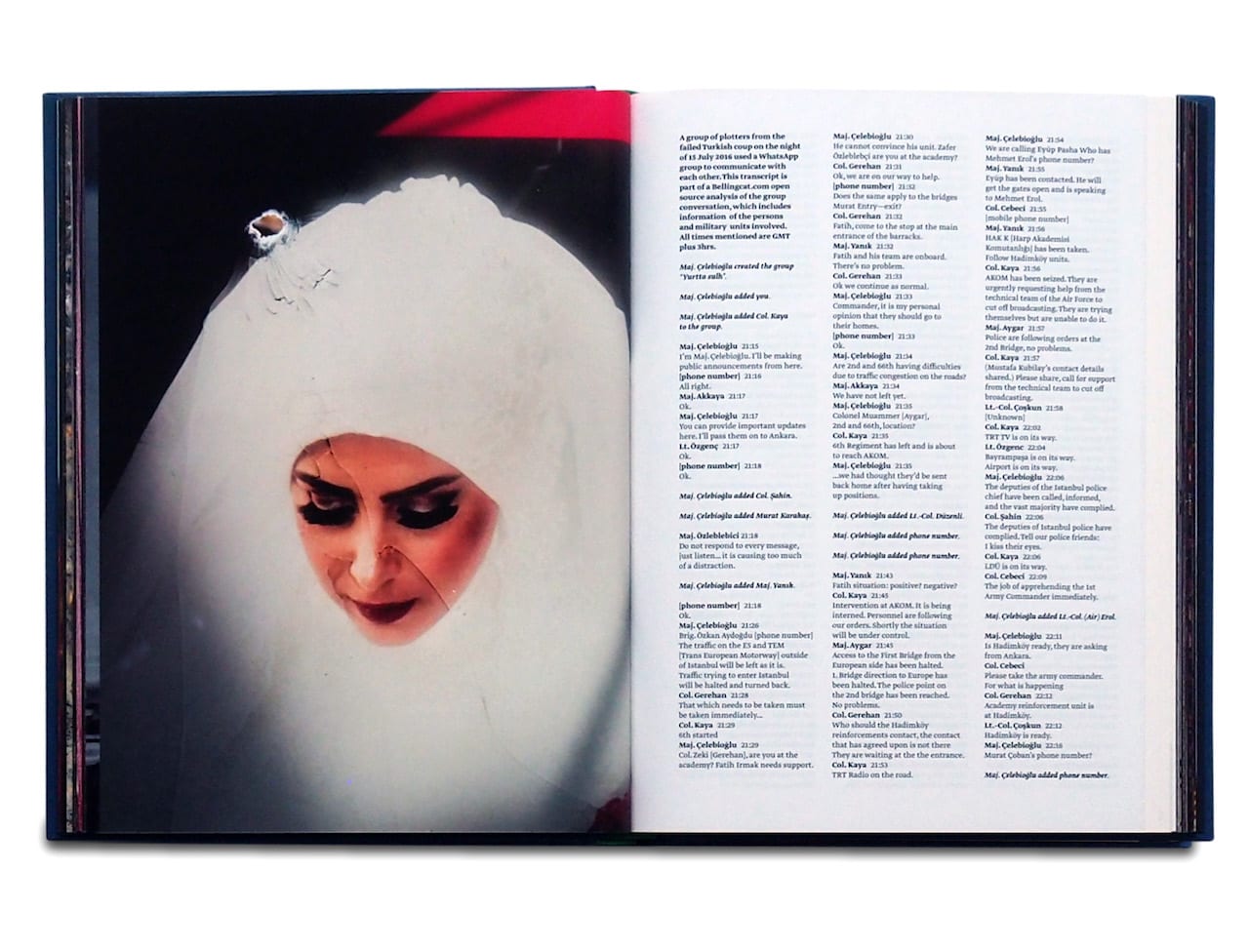

In October 2015 Ankara was bombed, in November 2015 Turkey shot down a Russian plane, in March 2016 Ankara was bombed again, in July 2016 an attempted coup took place in Istanbul. By starting to shoot soft power at the end of 2012, Martin had started to shoot the news before it had even happened – and before current affairs in Turkey became “these Bond movie plots, these crazy Hollywood scripts that you would think couldn’t possibly ever happen”.

And he was also acutely aware of the immediate impact of media on those being recorded or filmed, and the sense of performance it adds to everyday life. He had seen protestors in Benhgazi, Libya unfurl a bed sheet so that they could watch the news and see if they were on it; like many photojournalists, he’d noticed how peoples’ behaviour changed once he arrived. Added to that, he says, he’d seen how protesters use camera-phones and social media to show themselves.

“Turkey is a vibrant, modern, cosmopolitan country, with some of the fastest 5G and 4G networks in the world,” he says. “Everybody has a smart phone, everybody has a connection to a screen, to acknowledge that, to put it in the work, was really important to me. And….what I’d experienced in Libya, when a group of Western photographers or film-makers or a crew from Al Jazeera arrived, I’d seen again in Istanbul. People changed their behaviour because I was near, and I found that a very powerful thing to acknowledge.

“I remember in Cairo people asking specifically if I was with Al Jazeera or not. If I was with a pro-government crowd, they were vehemently anti-Al Jazeera and believed I was a spy, but if I went with a younger, more social media engaged or anti Murbarack crowds, I’d be accepted and welcomed as ‘You’re here to help us, to tell our story’.”

As the project progressed, Martin also started to photograph the spectacular nature of contemporary political rallies, shooting the “telegenic” Kurdish leader Selahattin Demirtas or the female supporters who watch Erdogan “like he’s a rock star…like they’re at the front row of the Foo Fighters”. “I was looking at the crowd,” he says. “There was an element of the film star, the red carpet.”

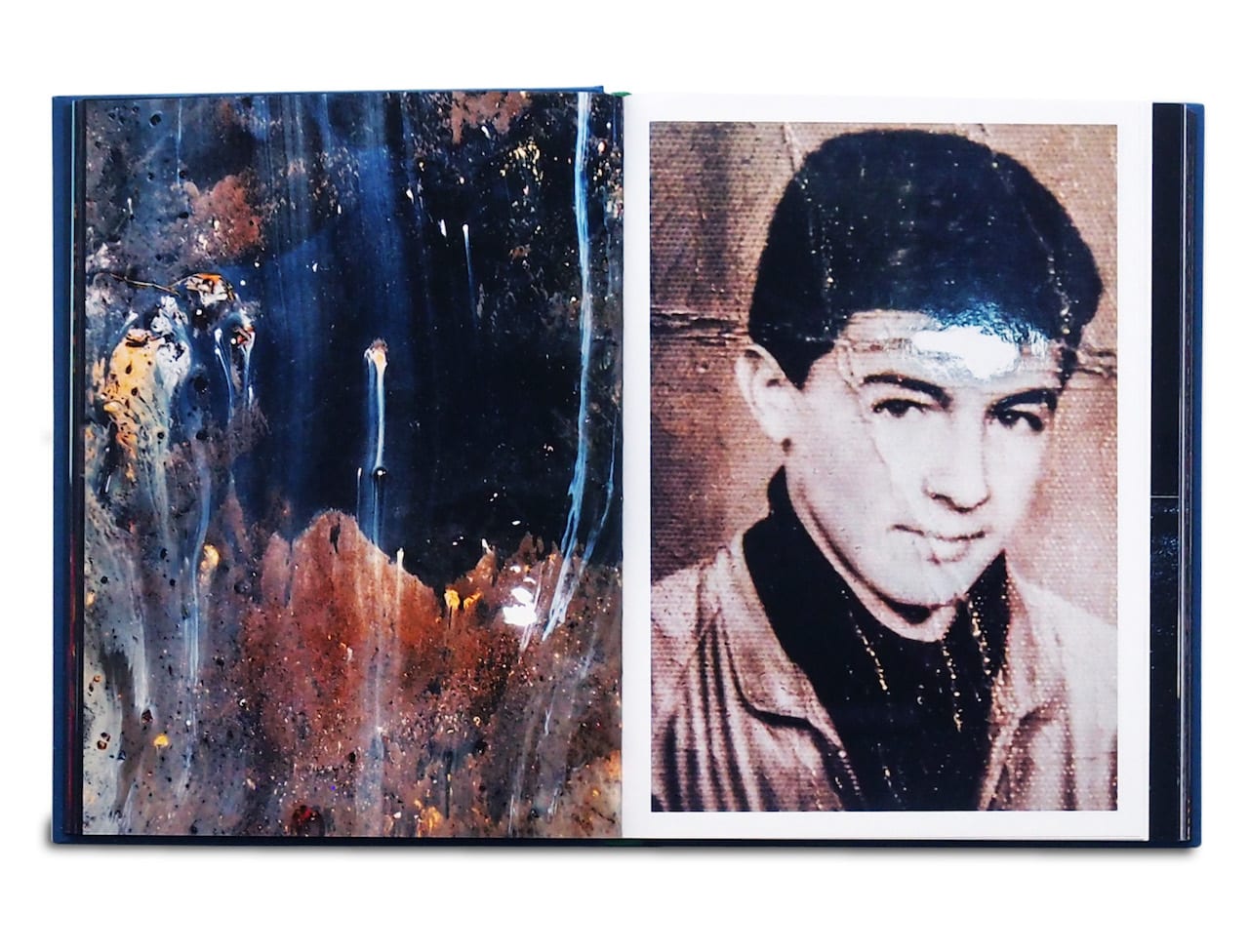

The result is a complex, multilayered project in which nothing is quite what it seems, and even the simplest image evokes a story. A seemingly-innocuous shot of a white Renault suggests the white Renault Toros used by Turkish death squads in the 1990s, for example – which were referenced by Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu in 2015. A hand reaching into towards a caged bird suggests Berkin Elvan, a 15 year old boy hit in the head by a tear gas canister in the 2013 protests, who is known as the “songbird who lost his wings” and immortalised in graffiti in Istanbul.

This complexity is the project’s strength but it’s also made it hard to boil down, says Martin, who finished the bulk of the photography in summer 2016 after the failed coup. He carried it around in a shoe box for months; taking it to Paris Photo he won several publishing offers, but decided to work with the designer Stuart Smith, who runs the publisher GOST. “I think he liked the fact that I wasn’t coming to him with a book dummy, I was more ‘Help me! I know there’s something in here, do you?’ says Martin. “And he did, he responded.”

For him, what’s essential is to avoid making neat conclusions. “Acknowledging the complexity of the times we are living in are essential to this work,” he says. “And to the work I would hope to make in future.”

When it came to the images, he was forced to find the core shots he could use to tell the story, he says; putting them into sequential order didn’t work so – appropriately – he decided to treat it like a storyboard. “I started off with this wide aerial image of Istanbul, then the next picture I’ve zoomed in on this Owellian landscape of teargas canisters going off in a grey car park. “It’s an image I shot three years prior,” he says. “I treated it like a movie.

“So then it was a question of how I tied it together,” he continues. “One image shows the Bosphorus at night, lovely blacks and purples shot on set, the next picture is very similar, showing the same kind of house also on a TV set, but with a mounted CCTV camera trained on it. The pictures taken were three years apart but they’re so different – in one Istanbul is so sexy and beautiful and brilliant, now it feels to me so much more sinister and foreboding.

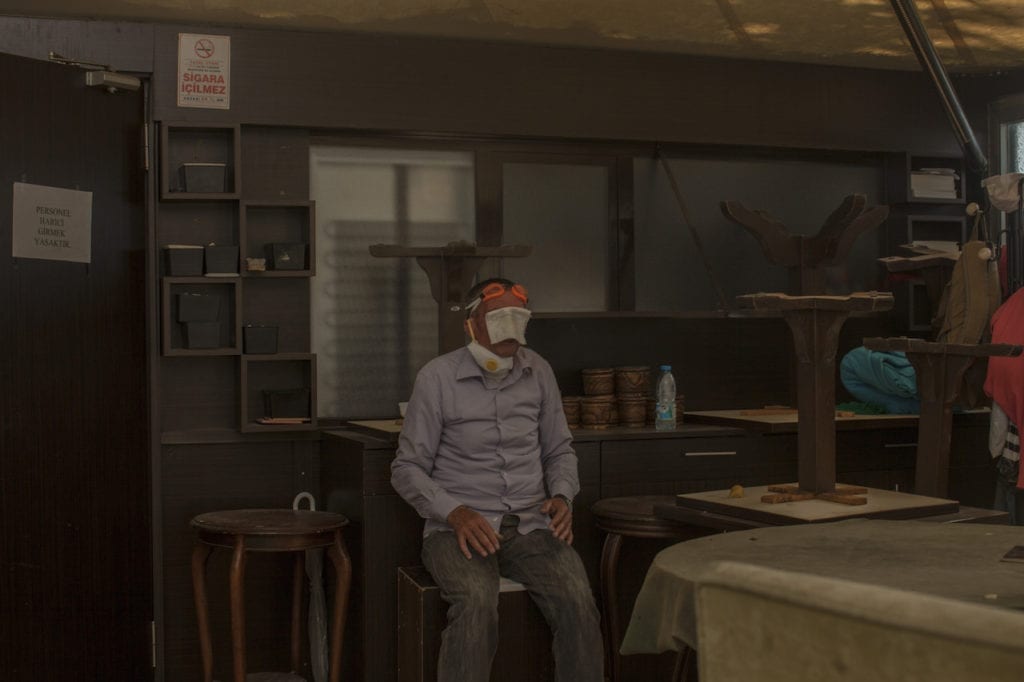

“Another is a picture of a man sitting down in a chair in a cafe with a white handkerchief over his face to stop the effects of tear gas; next one is this woman sitting down, she’s on a TV set but also has the same expression. There is this duality of images, but they were also storyboarded out.”

And, he adds, his series now feels uncannily relevant in the West. “It just so happens that now, where I’m from in the West, it has metaphors and bigger issues that we are seeing coming out in our politics,” he says. “And that’s very scary for me, that the things I’ve seen in Turkey might be like a microcosm.

“My project might hopefully be a warning – see what happens when you tell the media that they’re fake news, when you have supporters and media that just support you, that hang off your every word, and you say everyone else is wrong. I’ve seen what happens in that vacuum, and that’s very sobering for me.”

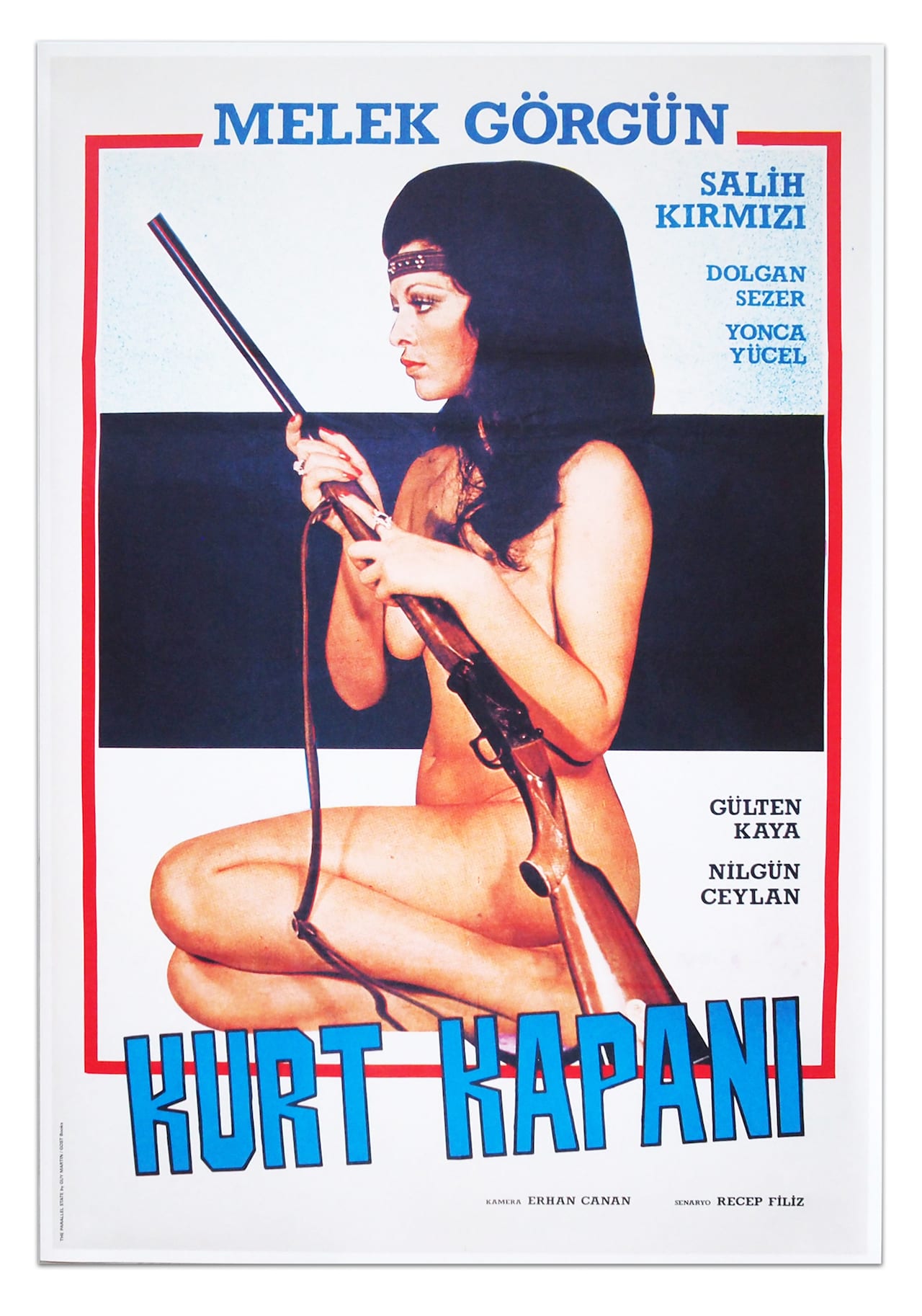

guy-martin.co.uk. The Parallel State by Guy Martin is published by GOST, priced £50. The book is also available in special editions featuring original Turkish film posters collected by the photographer. Visit the GOST website for more information www.gostbooks.com/product/the-parallel-state/ A slightly different version of this article was first published on bjp-online in January 2017.