It is estimated that 7% of the prison population in the UK has a learning disability, compared to around 2.2% of the general population. A study by Prison Reform Trust in 2008 found that people with learning disabilities are seven times more likely to come into contact with the police, five times more likely to be subject to control and restraint, and three times more likely to suffer from anxiety or depression, and spend time in solitary confinement.

These numbers are estimates rather than straight statistics because there is often no system in place to screen, identify, and record whether a prisoner has a learning disability. In a research paper from 2005, psychologist John Rack estimated that around 20% of prisoners have some form of “hidden disability” which affects their performance in education and work settings. It’s worryingly disproportionate, and it begs the question – if prisons don’t have systems in place to even identify these people, how can they begin to give them the support they need to survive in a prison environment?

“It was really shocking. I had no idea that people with learning disabilities got sent to prison before I started this project,” says Polly Braden, who for the last two years has been investigating what happens to the people who “slip through the net”, whose disabilities aren’t “bad enough” to get help.

Four years ago, while working on Great Interactions, a book about people with learning disabilities, Braden met a man who was in danger of running into trouble with the police. People with learning disabilities can struggle to understand, and to be understood by others, so it’s all too easy for them to get into trouble, says Braden. “It made me wonder what happens to people who get lost in this system.”

Working with arts organisation Multistory and writer Sally Williams, Braden met with KeyRing, a charity that supports ex-offenders with learning disabilities. They ran workshops in several support groups, explaining the project and how people could be involved. “It took a long time to find the right people,” says Braden. “Consent was a major issue, because people are telling very sensitive stories.”

They had meetings at a prison with the plan to run workshops, but after three they were unable to get further access due to “security reasons”. “There are lots of gatekeepers, that’s true for most photography projects, but prisons used to be places where journalists, given the right amount of time, were allowed in,” says Braden. “If they aren’t prepared to let journalists and photographers in to tell stories, then you’ve got to worry.”

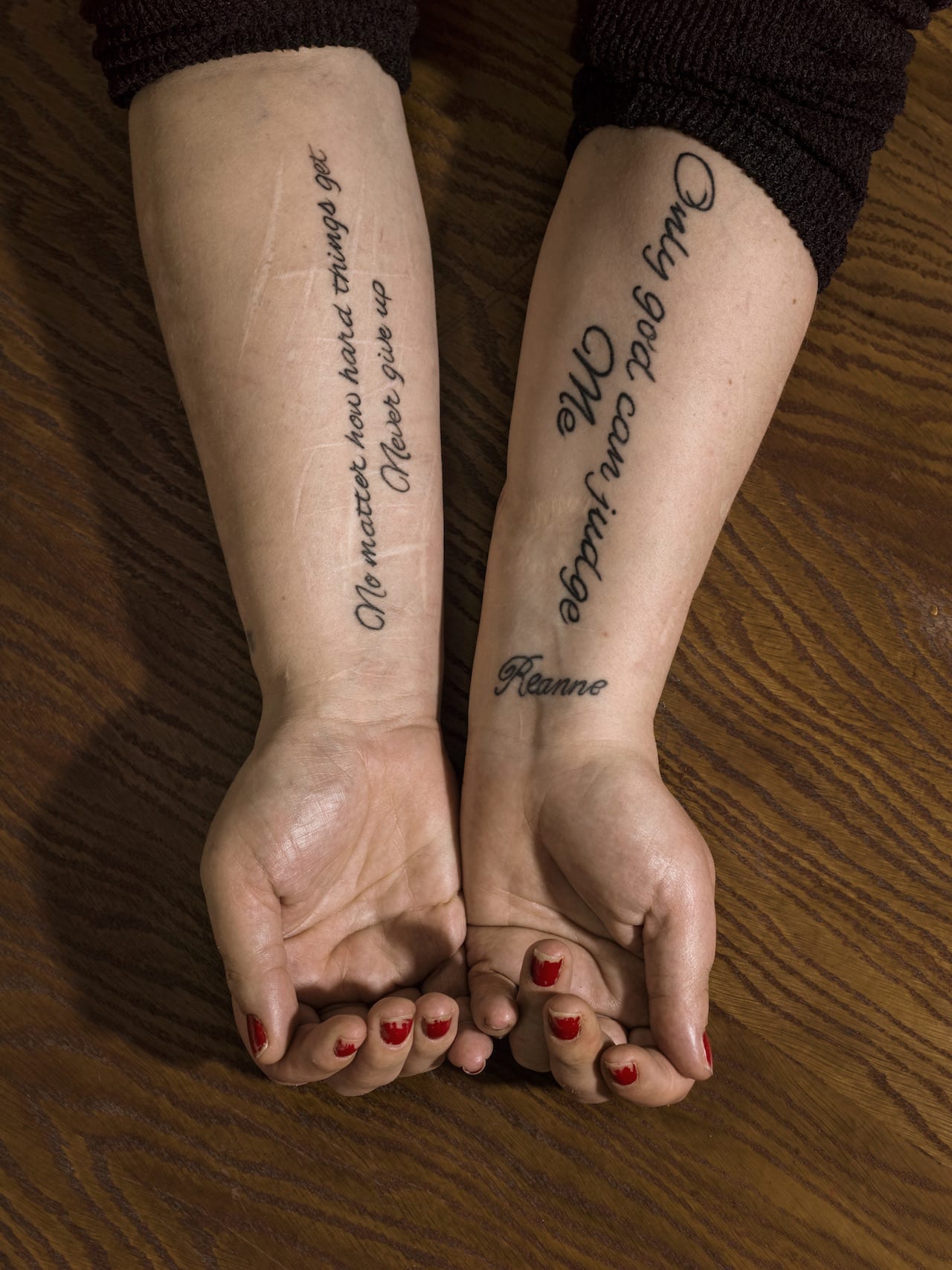

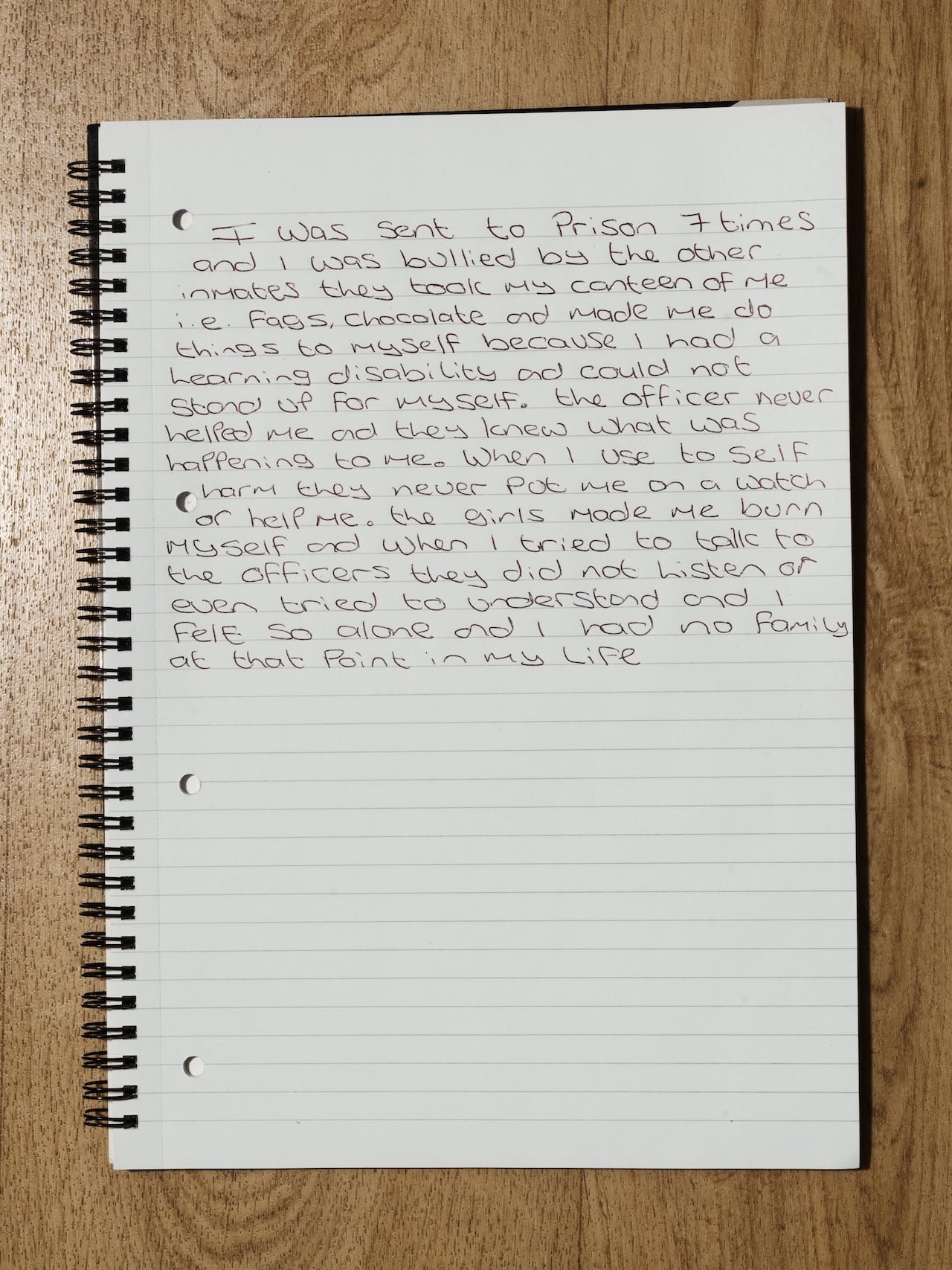

The resulting book, Out of the Shadows, tells the story of ten adults who have been in contact with the criminal justice system. Their experiences vary. Rodney, 49, spent 30 years of his life locked up for various crimes, including setting fire to his parent’s kitchen. Lindsey, 41, served a two and a half year sentence for burglary after escaping her manipulative pimp and becoming homeless for six or seven months. John, then 19, spent time in a detention centre after being coerced by local teenagers into prank-calling the police about a bomb threat.

While most of the subjects are now in rehabilitation, some, like Roy, are still locked up in institutions. Roy is a 50-year-old patient at a secure hospital for people with learning disabilities. He was physically and sexually abused for most of his childhood by his father, and then, after his father’s death, at a children’s home. As a cry of help, Roy set fire to a mattress, which was interpreted as a criminal act. Roy found comfort in the rigid and organised system the youth treatment centre so once released, he set another fire. In 1998 Roy was was convicted of arson, and from then on he disappeared into the prison system. Over 20 years he was transferred to 20 different prisons.

Braden recalls meeting with Roy at the hospital, where they were made to sit in a separate room, because there was “trouble” in the main building. She could hear men shouting in the corridors, keys jangling, intense banging, “it was really stressful,” she says. Roy was tense with his hands clenched into fists, and drew a picture of men smashing their heads against walls. “That’s not normal for an institution,” says Braden. “It felt like no one was listening. The whole atmosphere felt so wrong.”

Braden’s photographs accompany each of the subject’s stories. Three are first person accounts, and the rest are told by journalist Sally Williams. Braden sat in on Williams’ interviews, but also spoke with each of the subjects herself. “In a way I wasn’t trying to make a beautiful photography book, I wanted to tell stories,” Braden reflects.

In between the portraits are photographs of drawings, notes and objects that help to narrate each individual’s life. Clocks kept cropping up, because for many people with learning disabilities, the idea of time – like figuring out how long it takes to get from A to B – can be challenging, explains Braden. This makes certain aspects of prison life tricky, such as understanding how long it takes for items like cigarettes and toiletries to be delivered from the prison canteen, or knowing that the food you order in the morning won’t be ready until lunchtime at midday.

Braden says that the project was frustrating and emotional, but also uplifting. There are lots of people, like Lindsey, who have found ways to cope and are integrating themselves back into society thanks to organisations such as KeyRing, which work hard to make life better for people in her predicament. Even so, if the estimates are correct and 7% of the UK’s prison population has a learning disability, then according to latest government statistics, today, there could be almost 6000 people in prison who are still struggling.

“It’s something that needs serious uncovering,” Braden says. “It’s not that people with learning disabilities shouldn’t go to prison, it’s just that the numbers are totally disproportionate.” Major concerns include whether a person with learning disabilities can get a fair trial, and if found guilty, whether they will be given the necessary support in prison.

The fault seems to occur at several points in the long chain of people and organisations involved. Cuts to funding for youth services is one problem, as is the lack of education for the police, and the staff inside the institutions. “Prisons seriously need to be sorted out,” says Braden, “the ministers need to step up, and look inside.”

But really, the biggest problem is society’s attitude towards people with learning disabilities. Every person’s story in Out of the Shadows is different, but the one collective experience they all have is the discrimination and hate that they have faced in their lives. “We need to be able to say, ‘That persons different, and that’s okay’,” says Braden.

www.pollybraden.com Out of the Shadows is a collaboration between Polly Braden, Sally Williams and Multistory, a community arts organisation based in Sandwell. It is published by Dewi Lewis and available to purchase for £20. www.multistory.org.uk