“I have still never seen the first work I made as a photographer,” says Sabelo Mlangeni, who started his career as a delivery boy for a local photographer in his hometown, Driefontein, four hours’ drive east of Johannesburg. The photographer he worked for had been asked to shoot a wedding but, unable to attend herself, asked Mlangeni to cover it – sending him off with a camera round his neck and a crash course in photography. After the wedding the newlyweds quickly picked out the images they wanted – so quickly, Mlangeni never got to see them.

Still, the experience of looking for a good photograph, and working with people from within a community, got him hooked, and in 2001 Mlangeni moved to Johannesburg and joined the Market Photo Workshop. Set up by renowned documentary photographer David Goldblatt in 1989, this well-respected organisation supported young black photographers during apartheid South Africa.

It was an excellent start in photography, but arriving in Johannesburg, Mlangeni felt alienated. “I couldn’t understand what people were saying,” he says, describing the struggle to communicate with people in English, which he was still learning at the time. To avoid speaking, he channelled his feelings into photographs of the buildings and architecture, which lead to his first, and ongoing, series Big City.

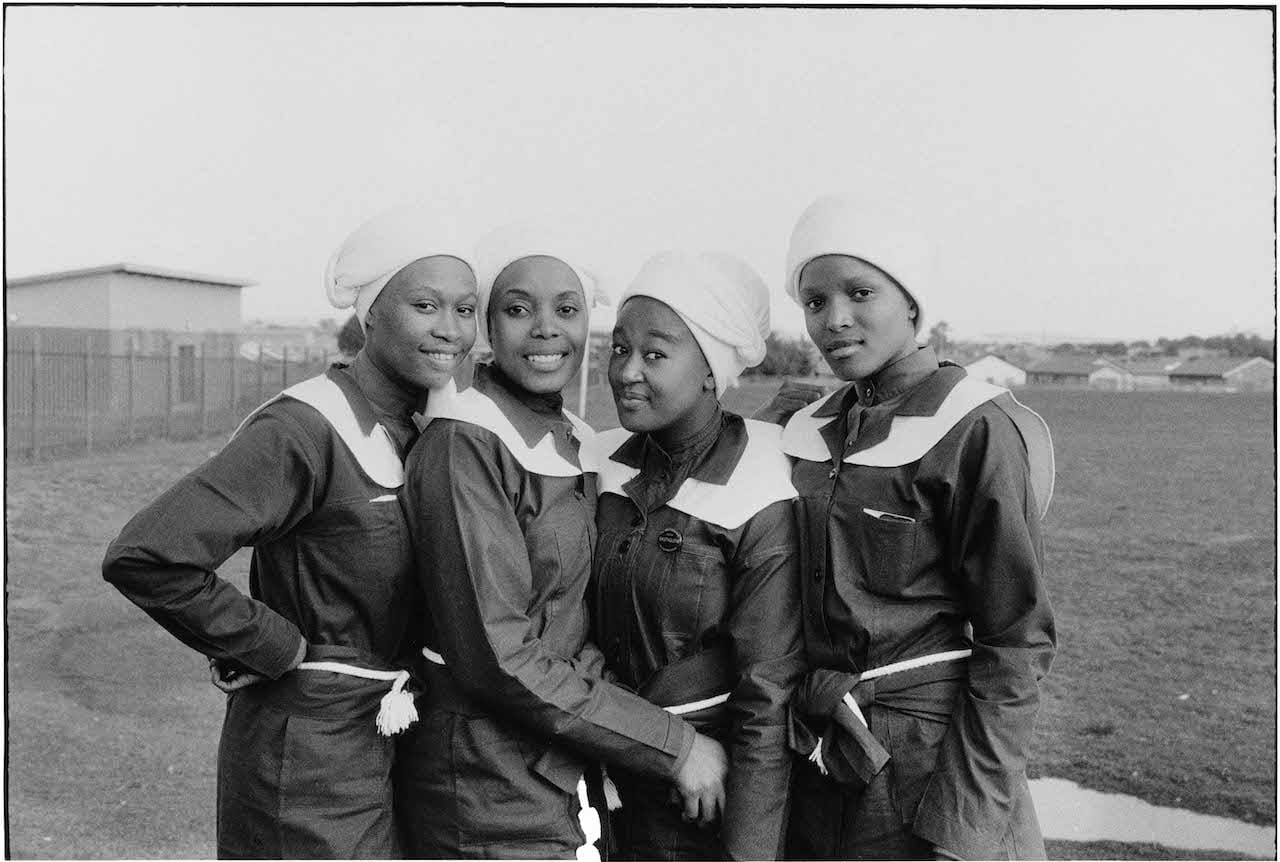

As he became more comfortable with the language, Mlangeni began to search for stories about everyday life. Struck by how clean Johannesburg’s streets were each morning, compared to how they were at the end of each day, he set out to find out who was sweeping them.

This led to a series called Invisible Women, 2006, which shows the women who sweep Johannesburg in the dead of the night – addressing some of the challenges they may face, working in the dark in one of the most dangerous cities in the world. After winning the first Africa Mediaworks Photography Prize this year, Mlangeni chose to show images from this series in London.

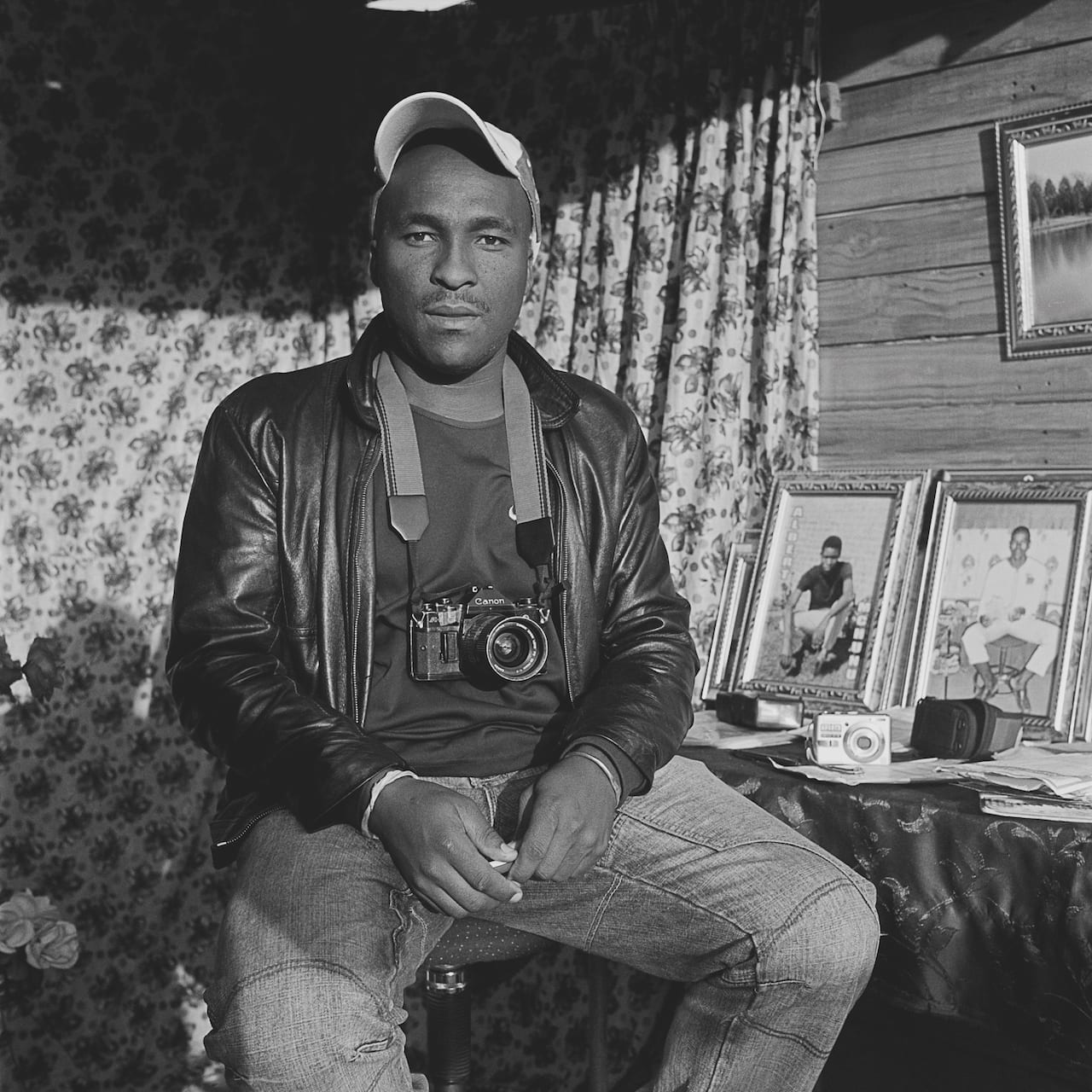

Mlangeni’s projects can take a long time; he tends to dip in and out of them, and return to the same places with a fresh eye and clearer understanding of the images he wants to make. But mostly, time is important because he values having a relationship with his subjects.

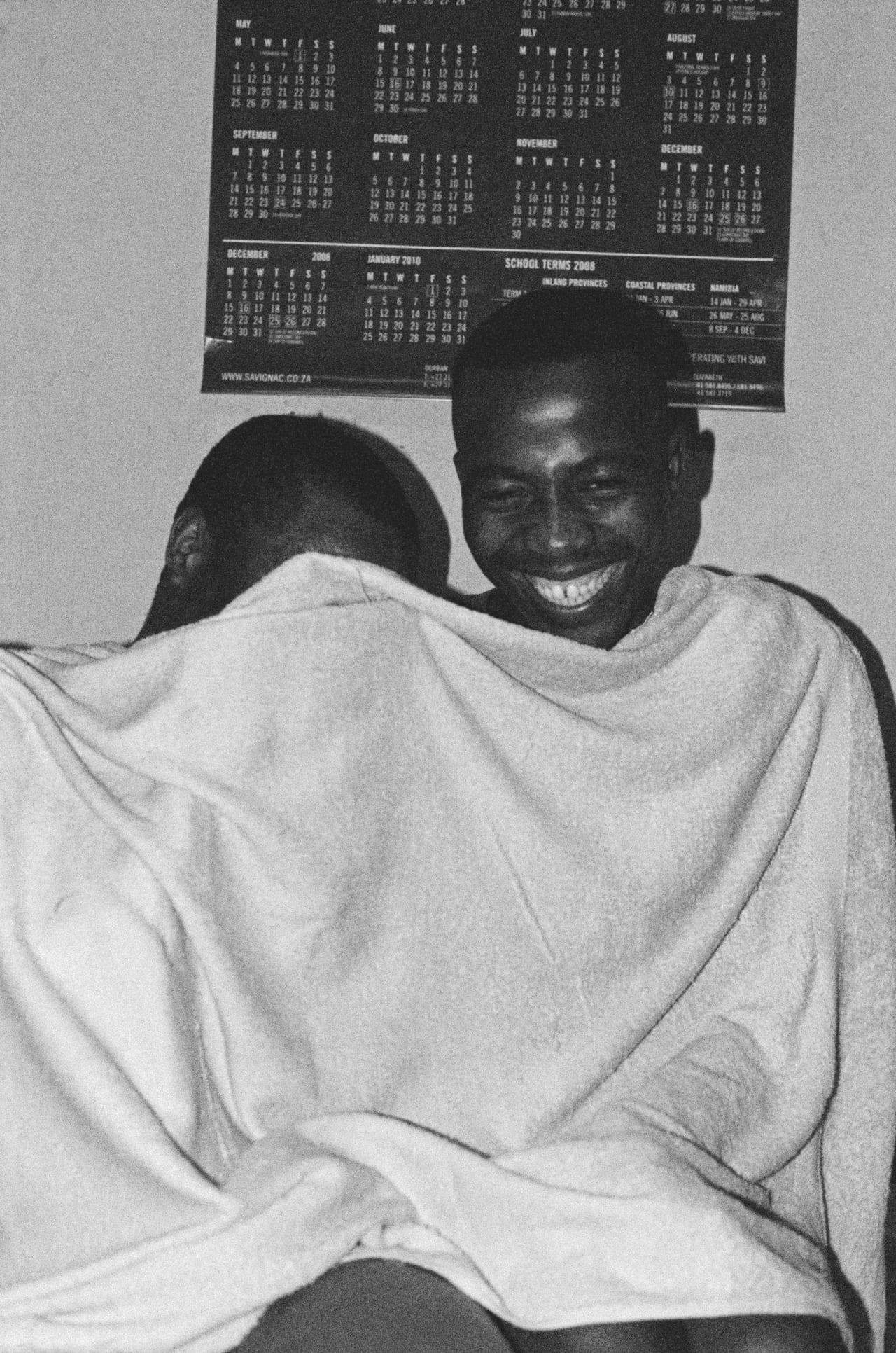

For Men Only, a project completed in 2009, Mlangeni spent almost two years photographing outside a men-only hostel in Johannesburg, before he was allowed to go inside. It’s intended mostly for migrant workers, and having got access he lived there for several weeks, sharing the tenants’ daily routines and photographing them in this transitional space, in which they often face violence, sexual abuse, and illegal trafficking.

“When I walked out of that place, I was completely broken,” says Mlangeni. “You know people for years, and become part of their community, but there comes a time where you have to close the body of work. Moving on after building this relationship, I find this very difficult.”

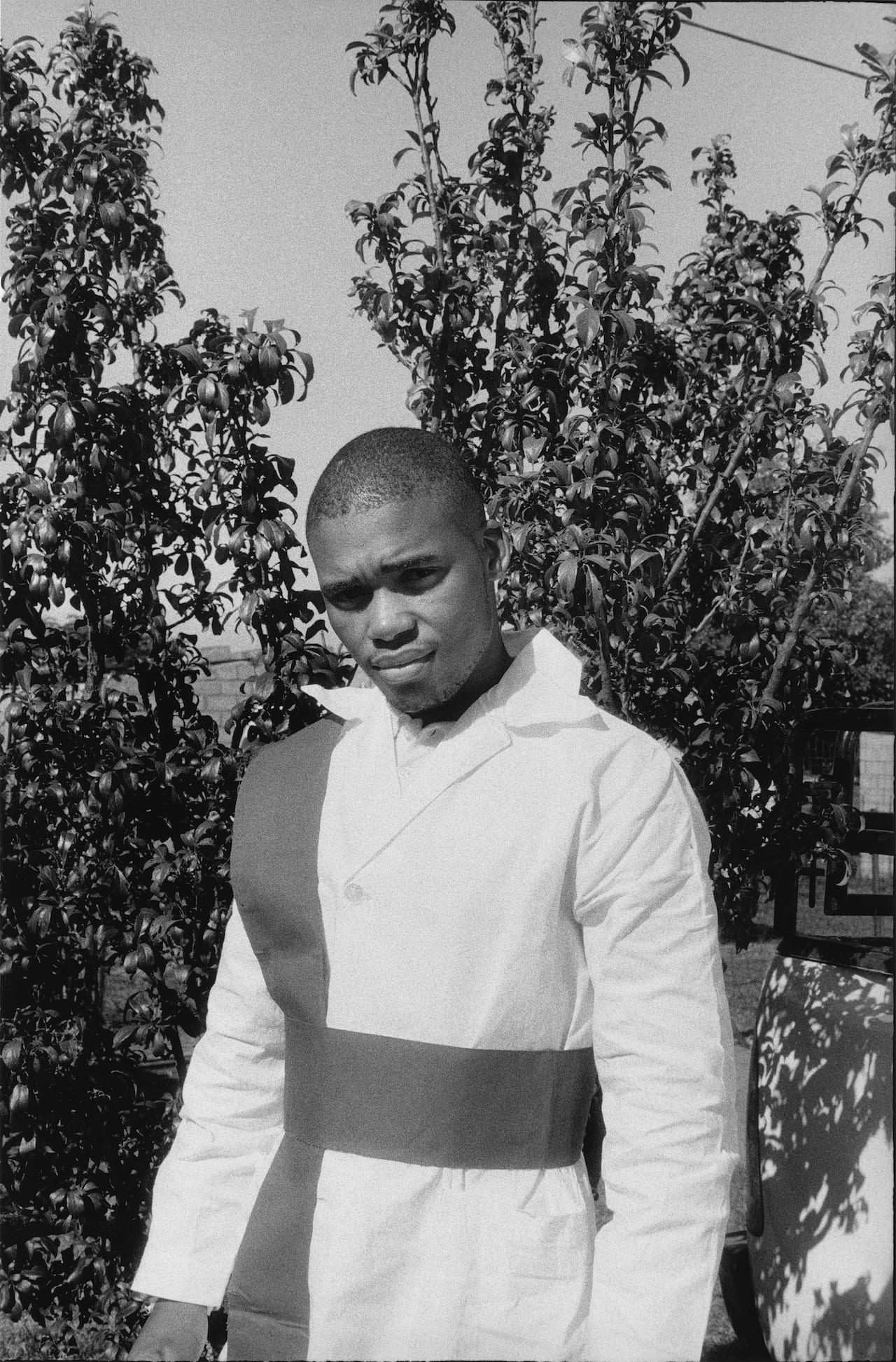

More recently Mlangeni decided to try something different and, also keen to get away from the urban chaos of Johannesburg, started travelling to small towns on the outskirts of the city. His more recent projects consider the shift that has taken place in these towns since the end of apartheid in 1994.

“It’s changing completely. I had questions about what the change means for the community that lived there before 1994,” he says. “How do they now try to negotiate the space?”

The Ghost Towns (2009-2011) are images of “forgotten towns”, lost in the changing South African landscape. “Roads were cracking, shops were closing, the infrastructure was falling down; something ghostly was going on,” he says.

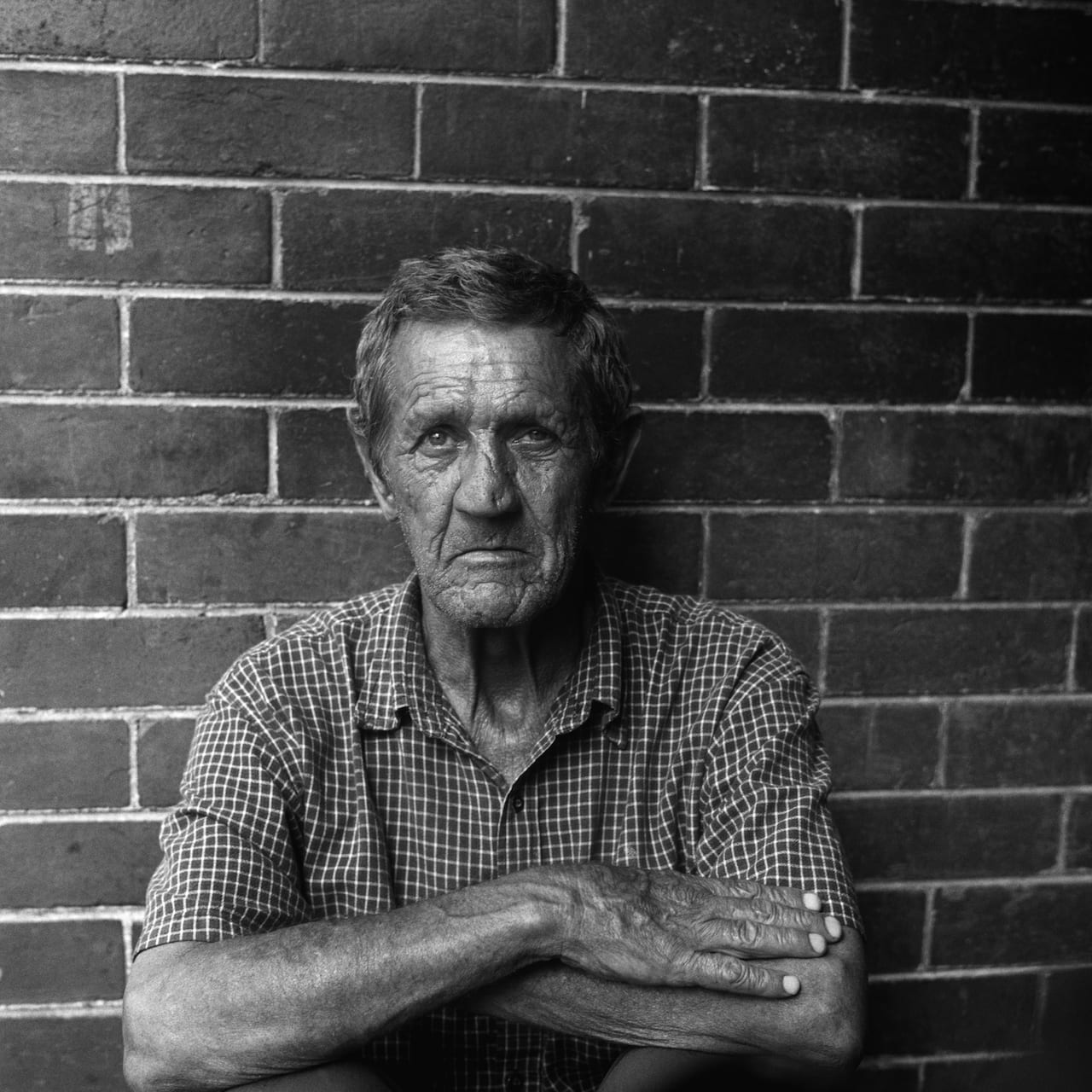

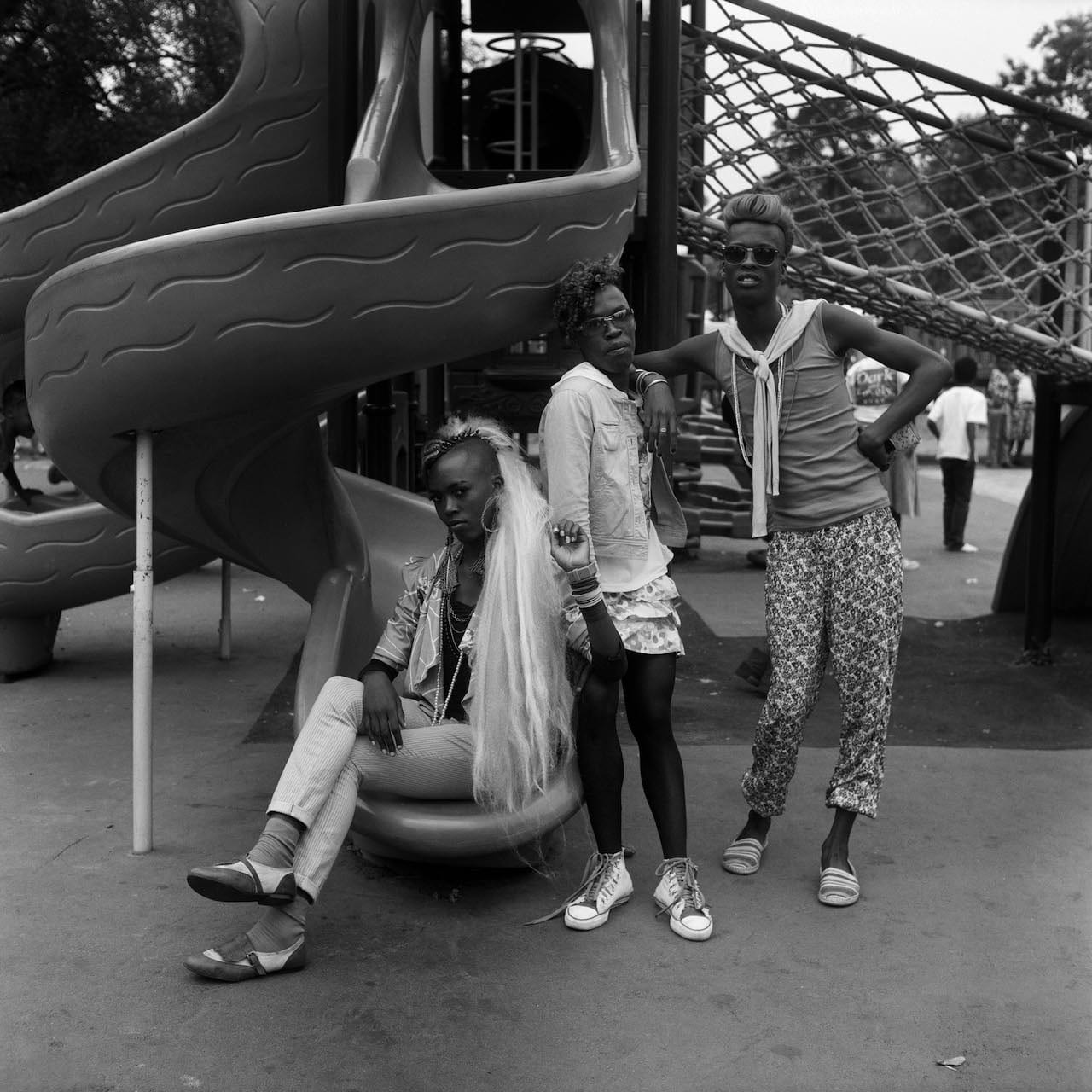

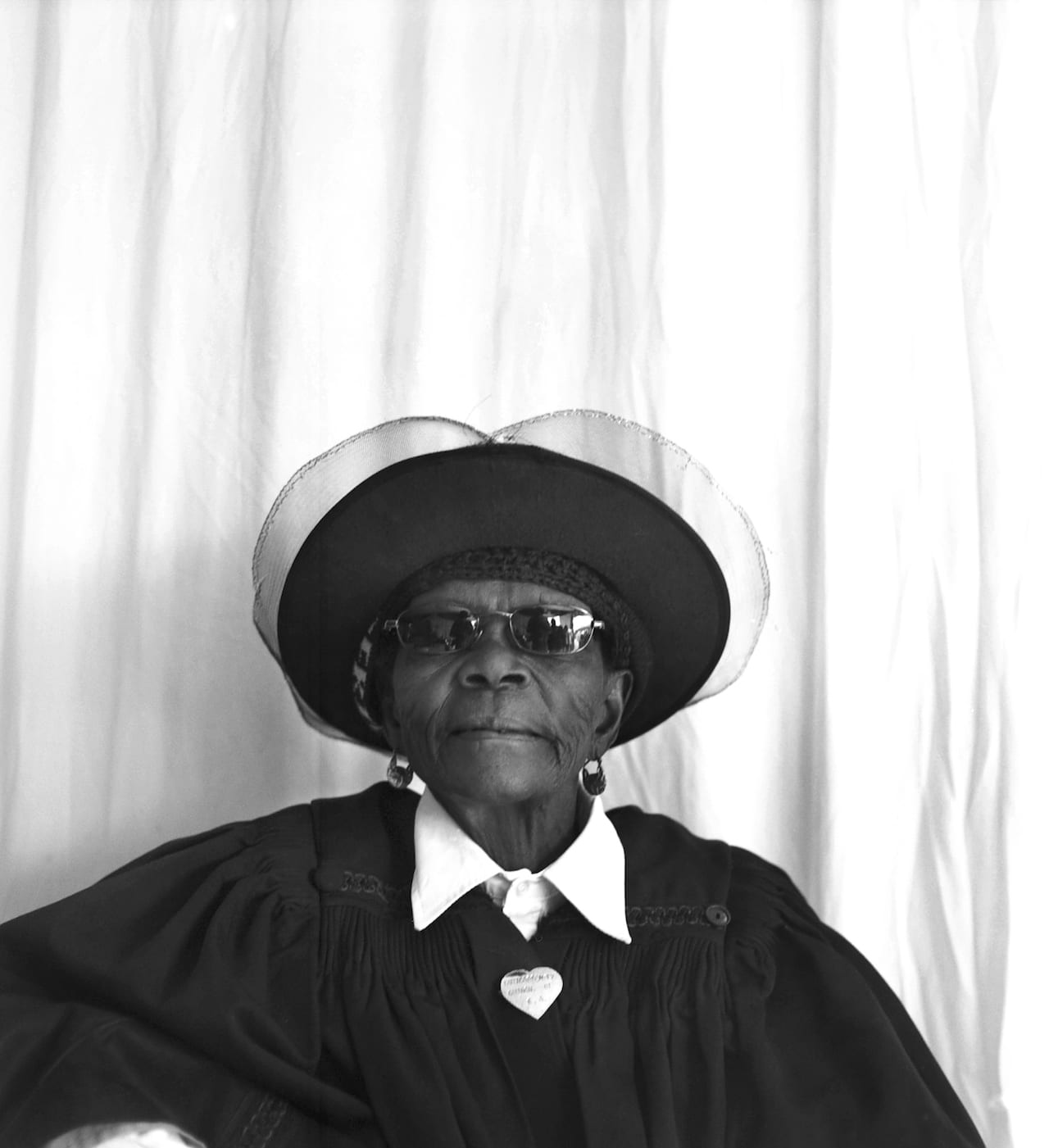

My Storie (2012) looks at a white community that lives in one of Johannesburg’s oldest suburbs, Bertrams, an area that has become increasingly poverty stricken, filled with derelict buildings, squatters, drug dealers and illegal immigrants. No Problem (2013), photographed during Mlangeni’s residency in the the suburb of Alexandra, visits one of the few urban areas in the country in which black Africans could own land during apartheid.

“The image tells the whole story,” he says, “I think they tell you about how these people feel about post-apartheid South Africa, within the spaces that they inhabit.”

Sabelo Mlangeni won the first Africa Mediaworks Photography Prize earlier this year, granting him an exhibition in London plus a £5000 award. The Africa Mediaworks Photography Prize is run in association with Nataal Media, The Guardian, and W8 Advisory https://amwphotoprize.com

Sabelo Mlangeni can be contacted via the Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town and Johannesburg https://stevenson.info