“They had this amazing enthusiasm; a very creative enthusiasm,” says Peter Kennard, the well-known photomontage specialist and early member of the radical collective Half Moon Photography Workshop. “Camerawork contained all the different debates that were going on in photography at the time, but it was practical as well. The whole thing was about democratising photography.”

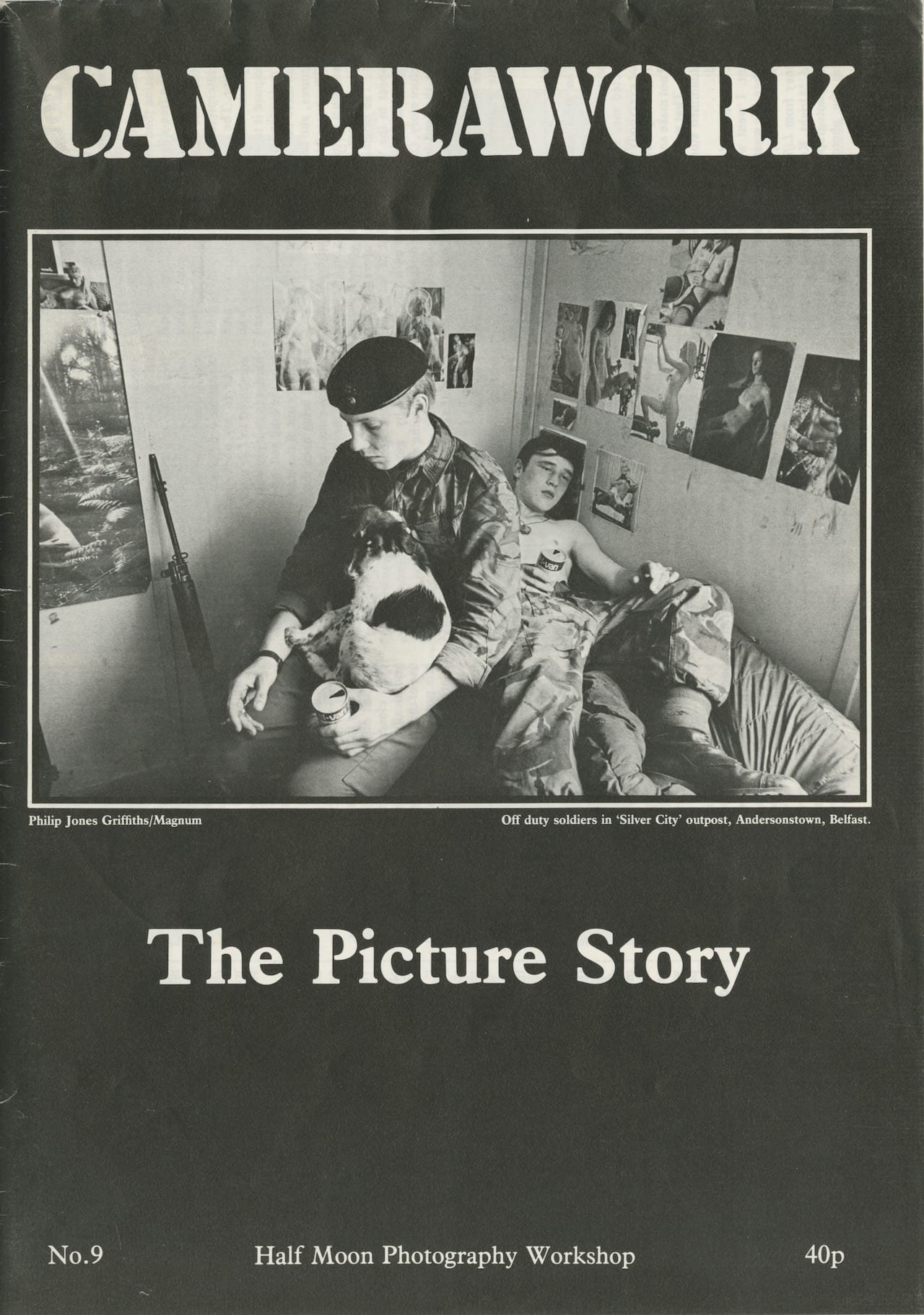

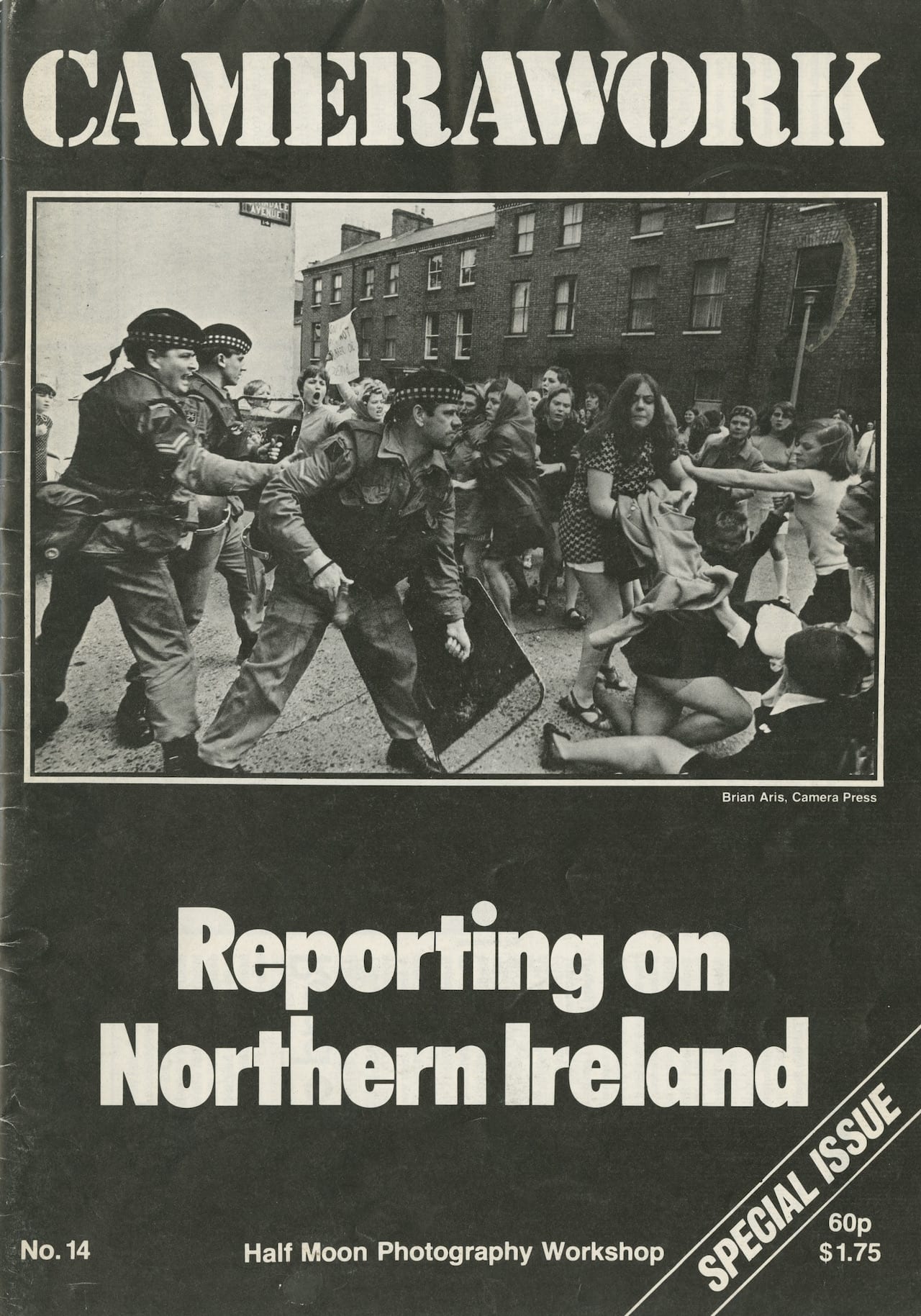

Radical Visions, a new exhibition at Four Corners in East London, reveals the lesser-known history of Camerawork magazine and its creators, the Half Moon Photography Workshop. The exhibition coincides with the launch of the Four Corners Archive, which has made all 32 issues of the magazine freely available to view online.

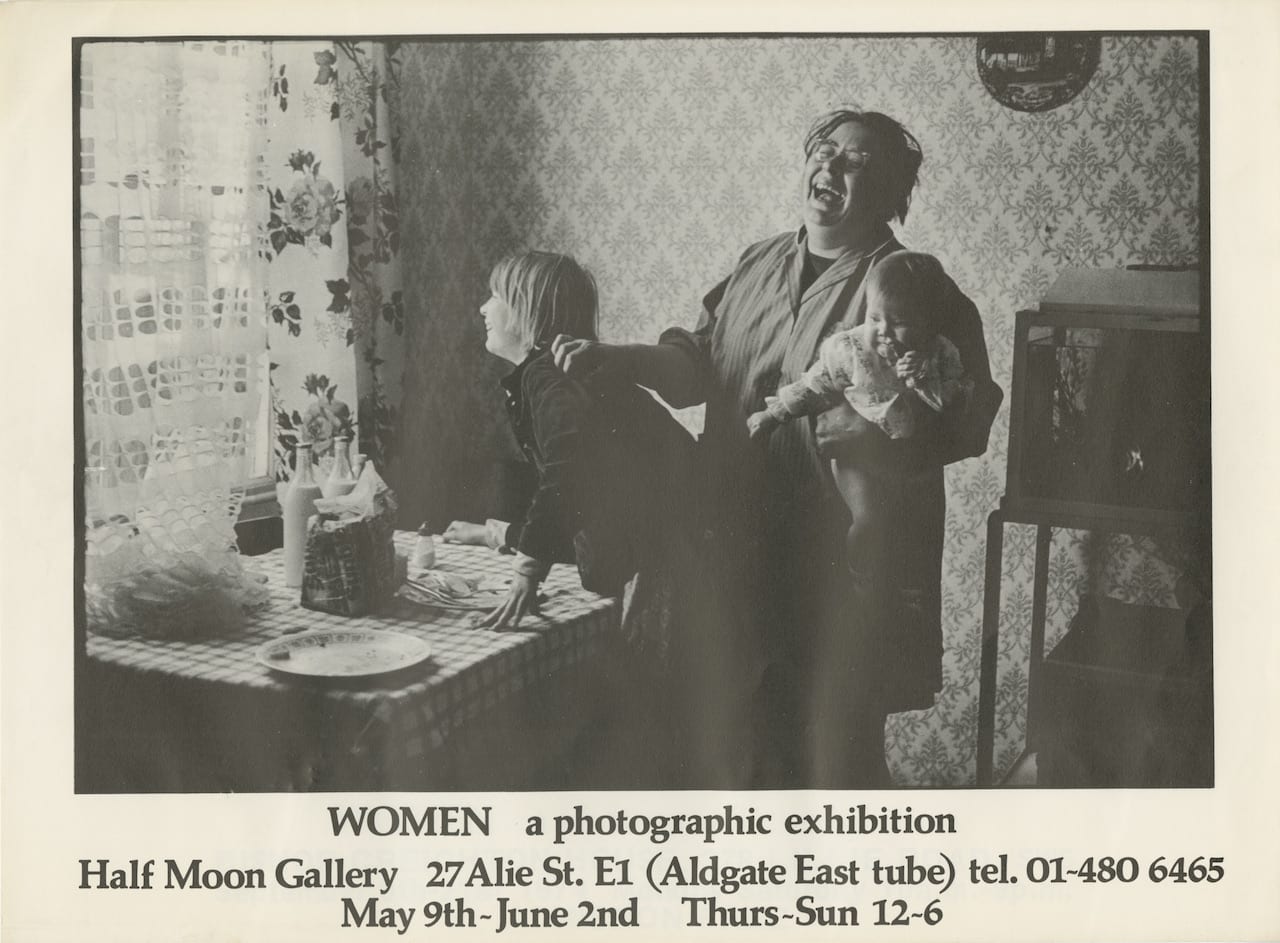

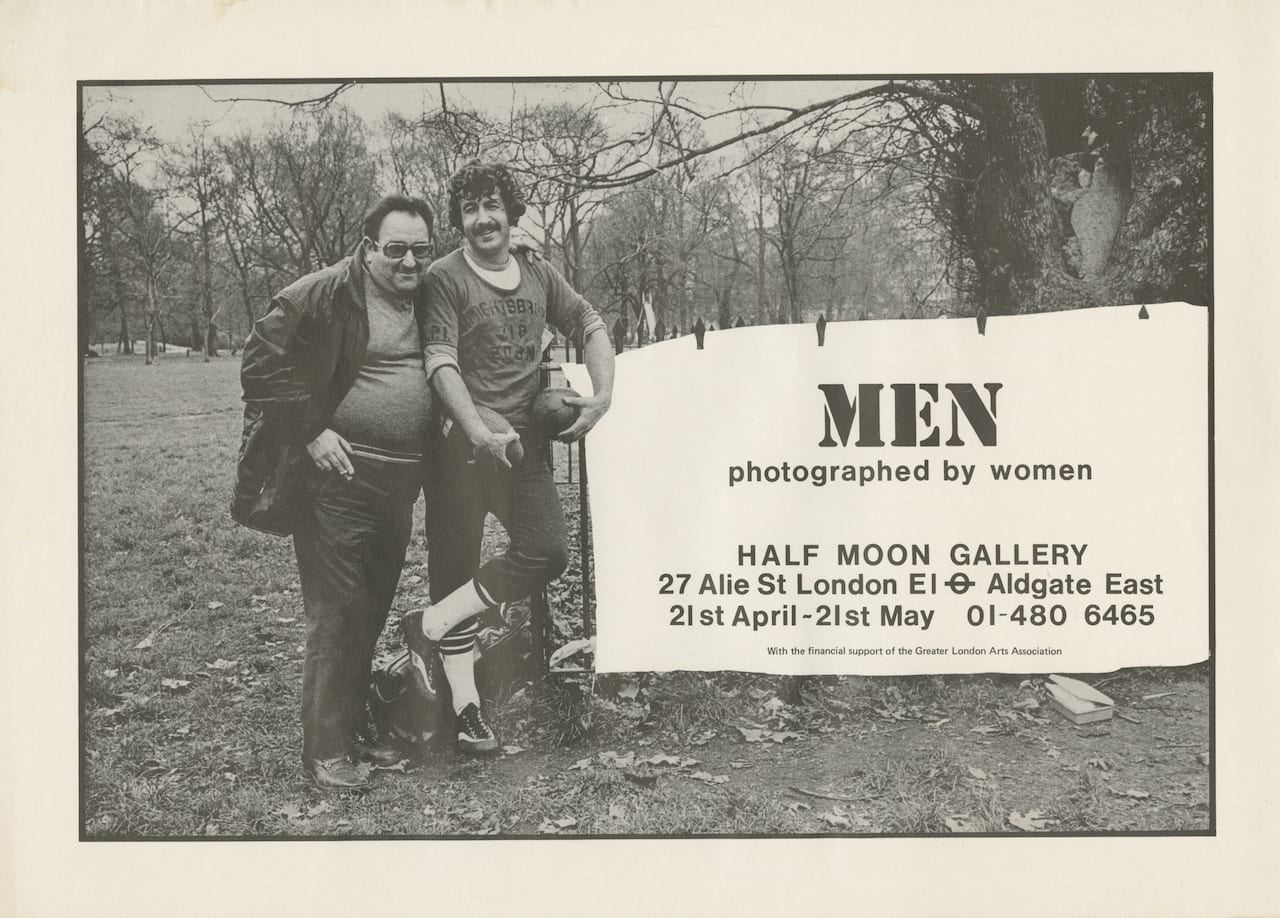

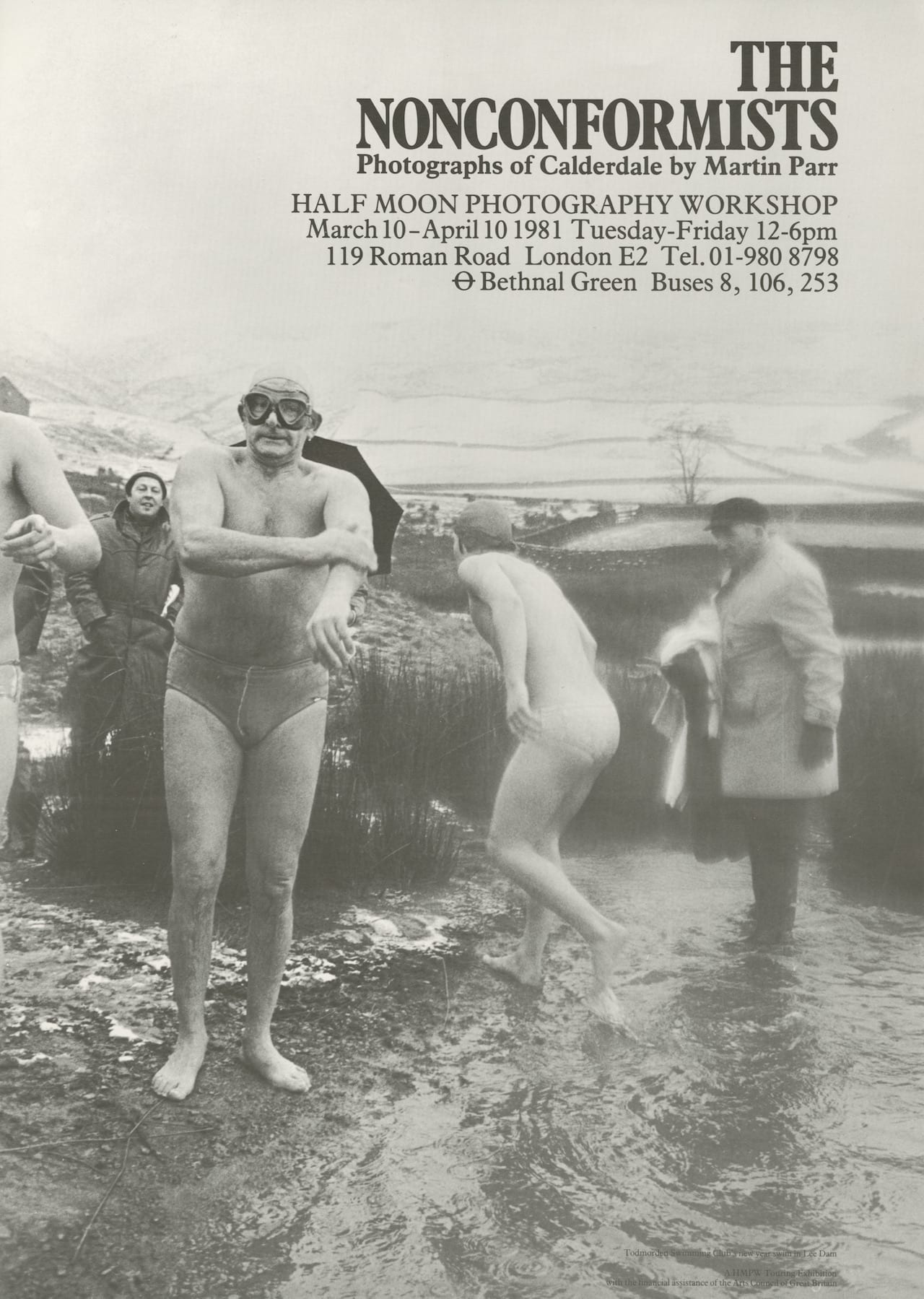

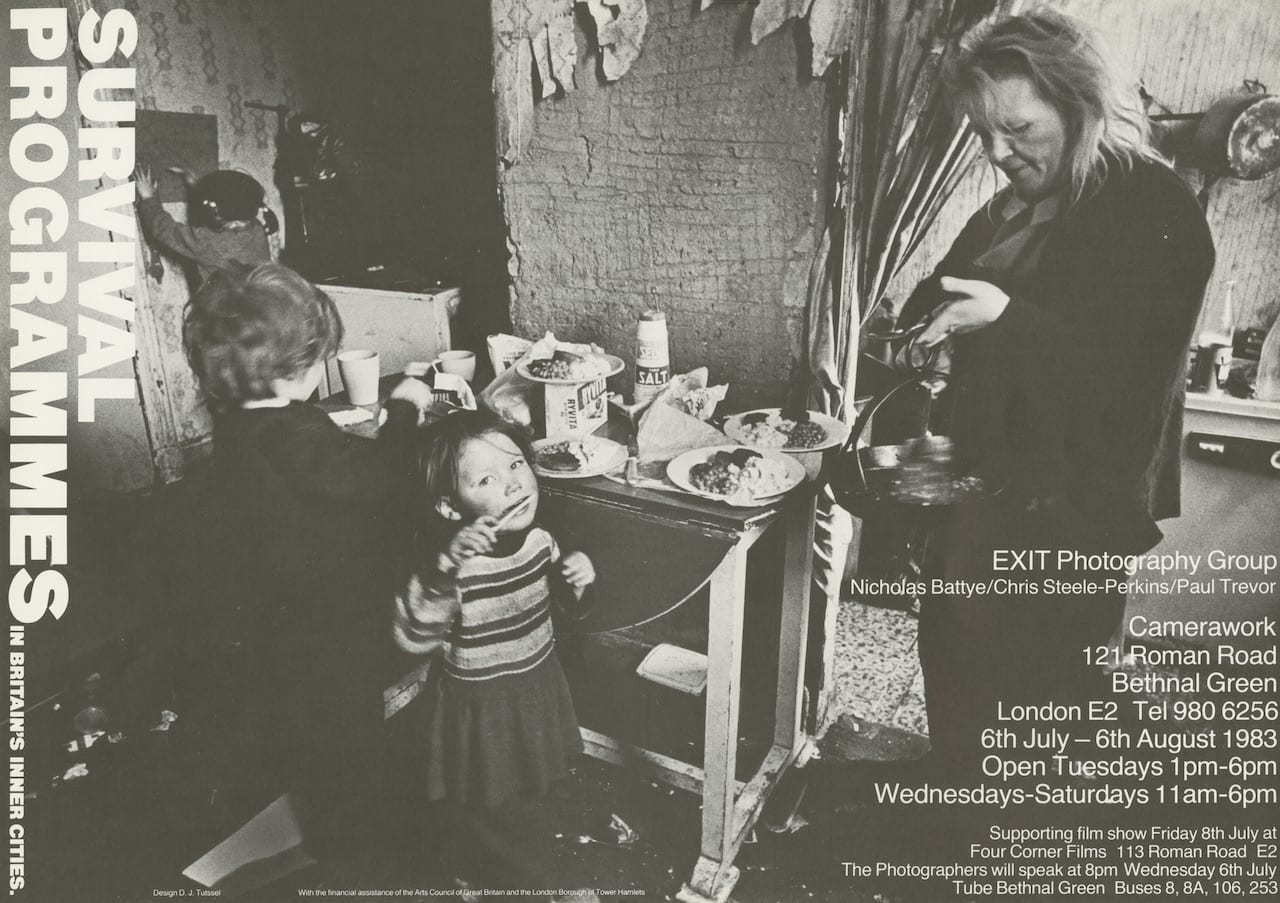

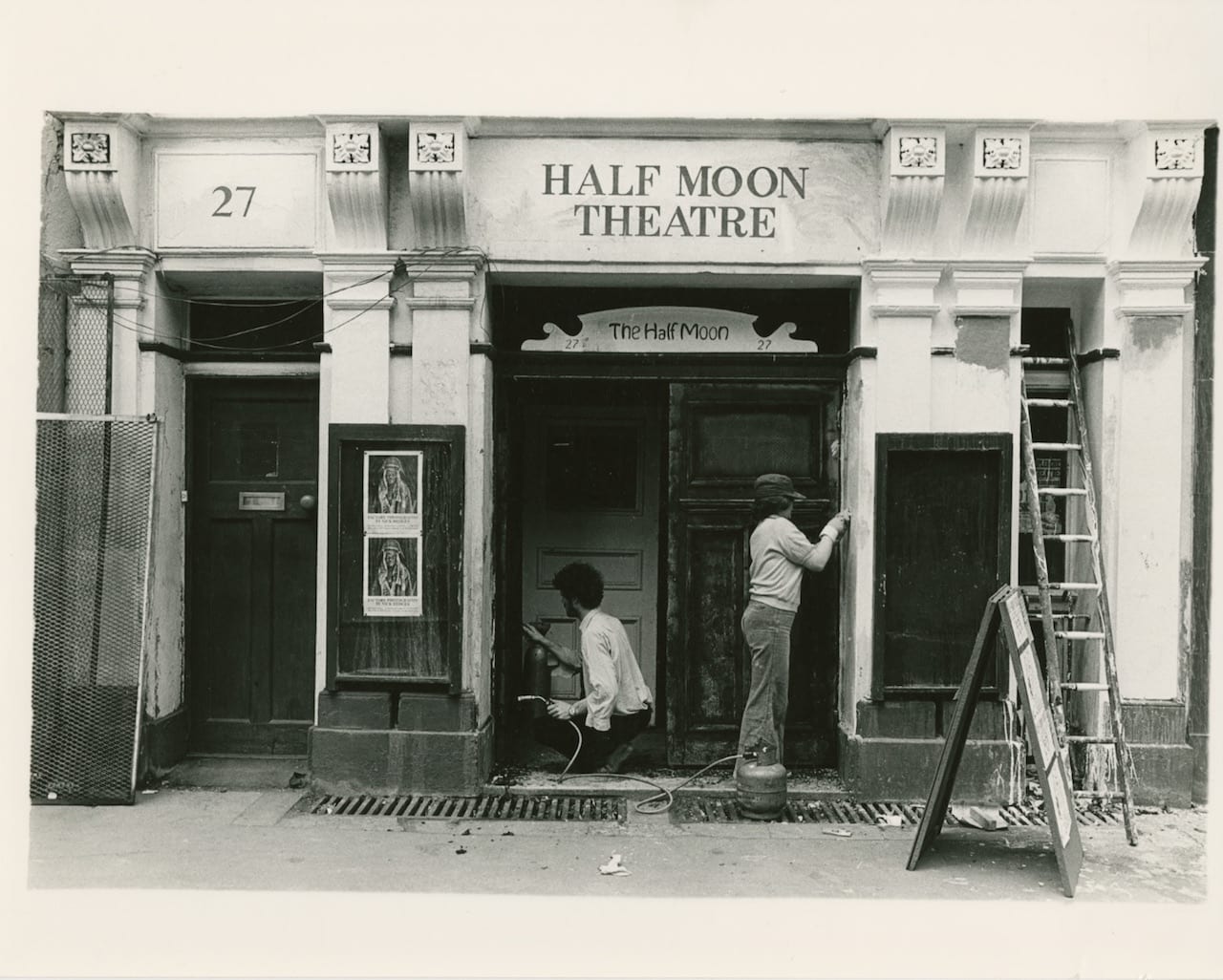

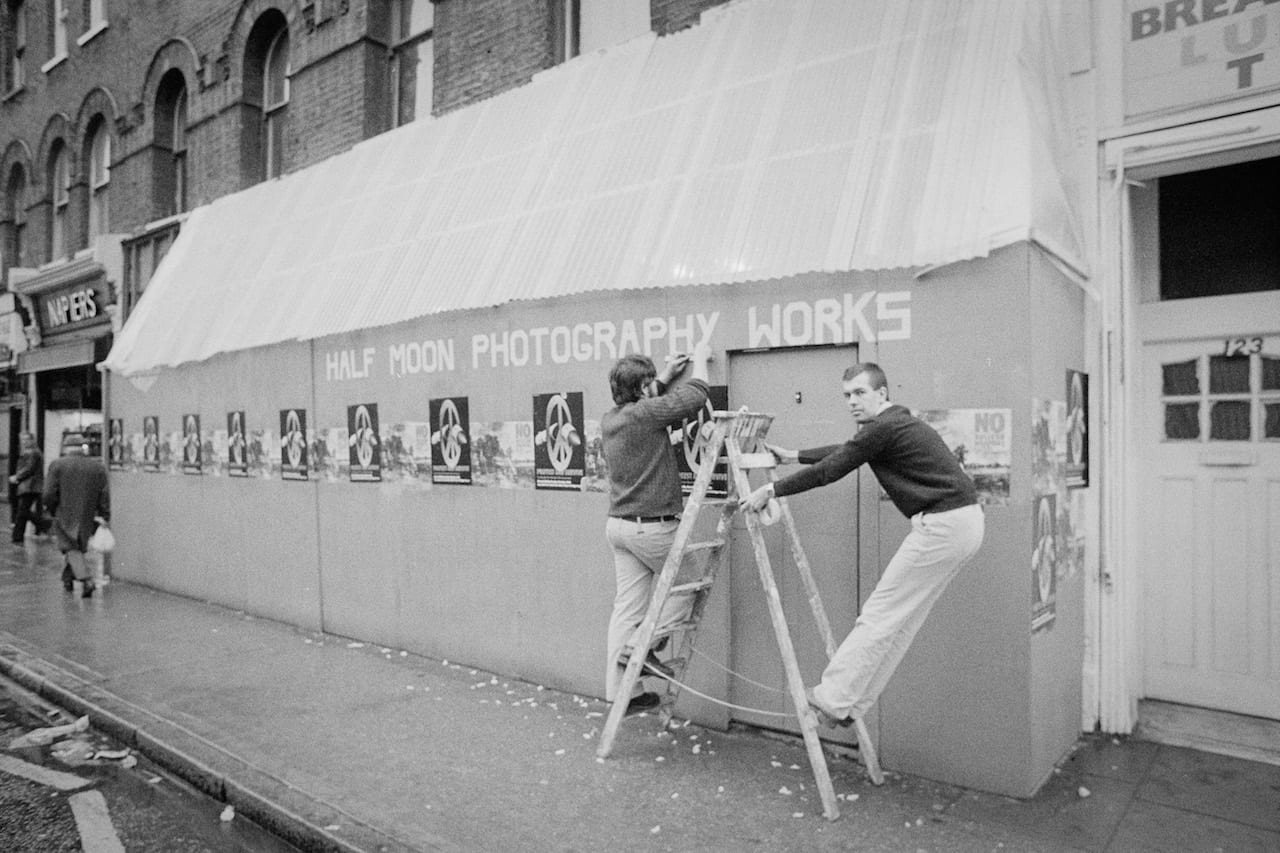

Born in 1972 as Half Moon Gallery, and running a gallery space of the same name, the collective pioneered debates on the politics of photographic representation in Britain. Becoming the Half Moon Photography Workshop in October 1975, it founded Camerawork in 1976 and moved to a new gallery on Roman Road in 1977 – the space now used by Four Corners. The collective took the name of its respected magazine in 1981.

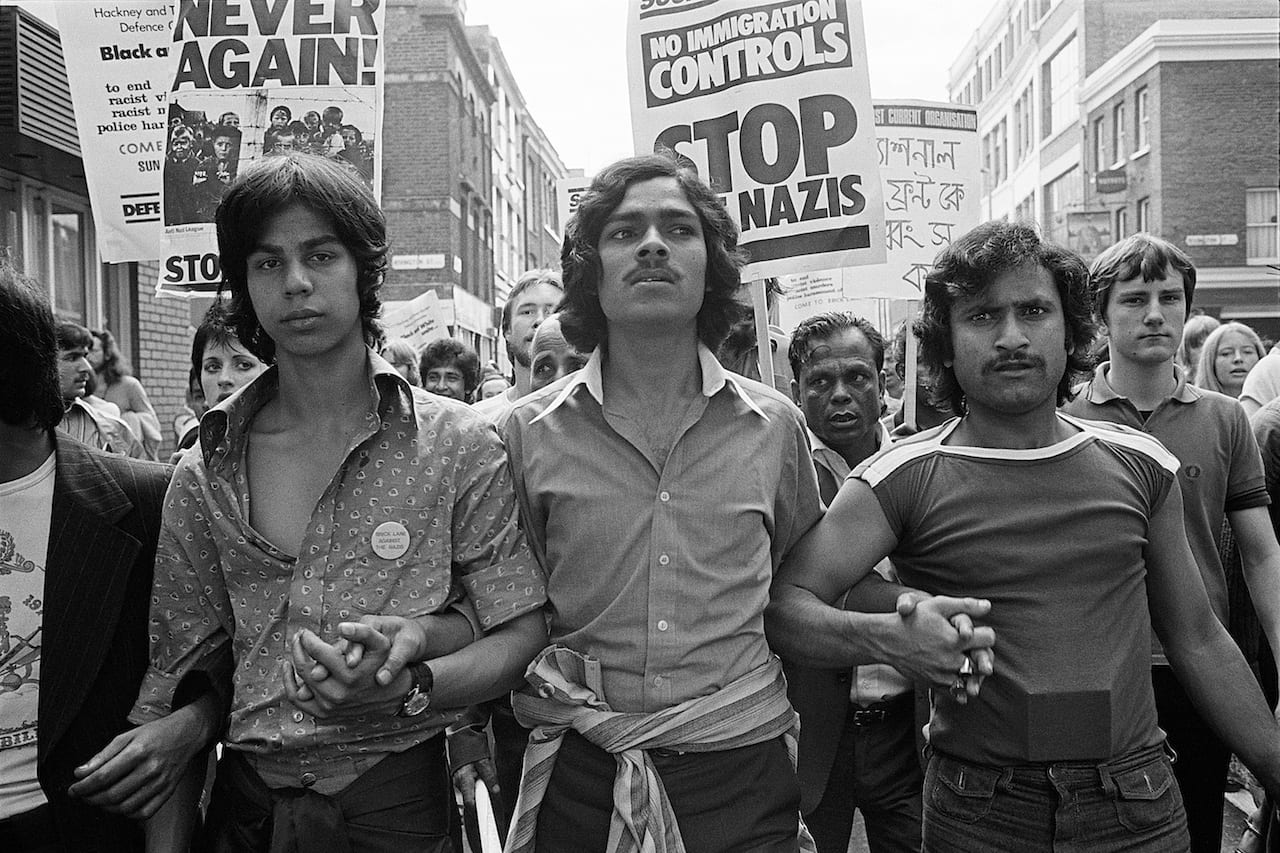

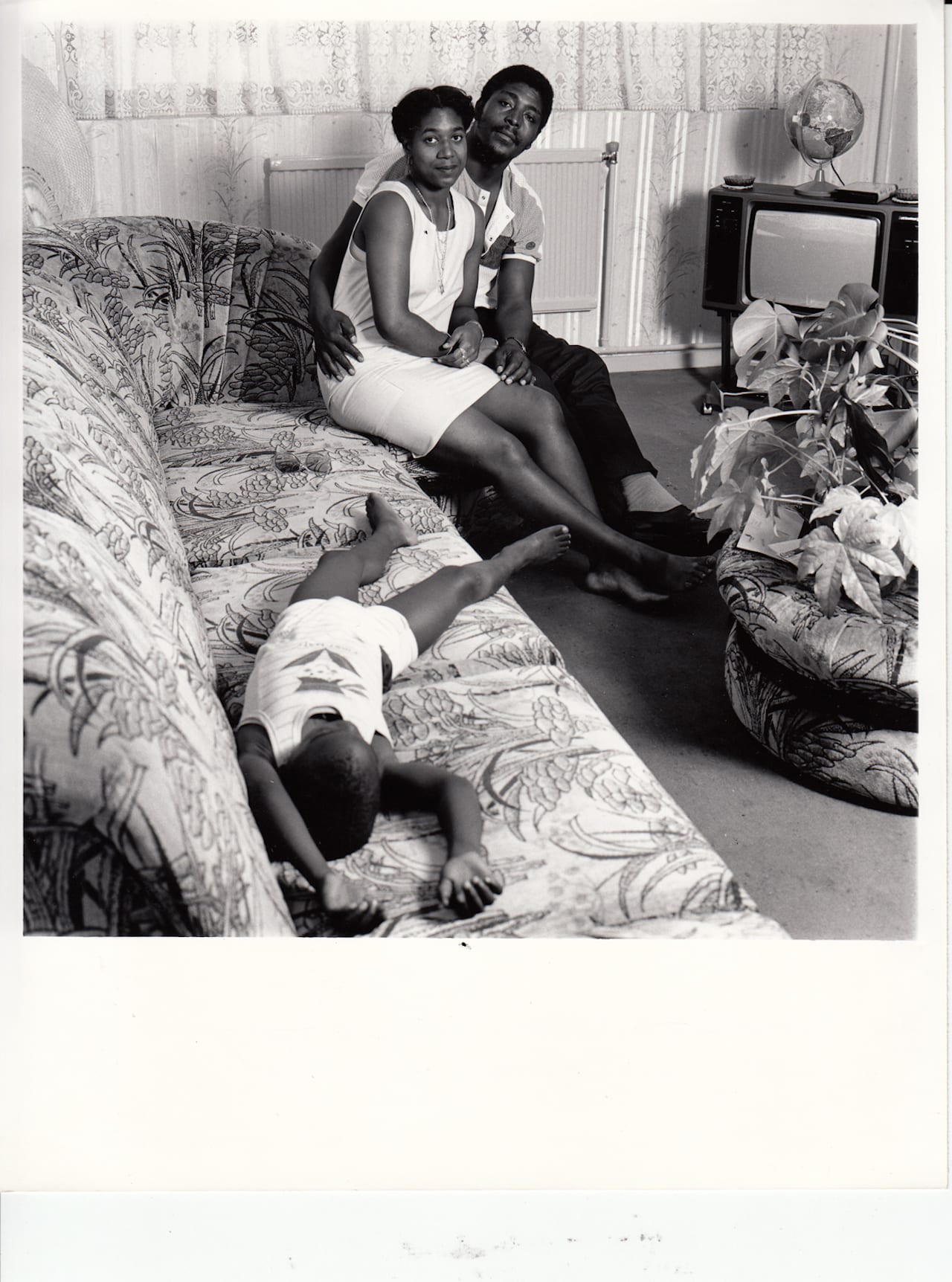

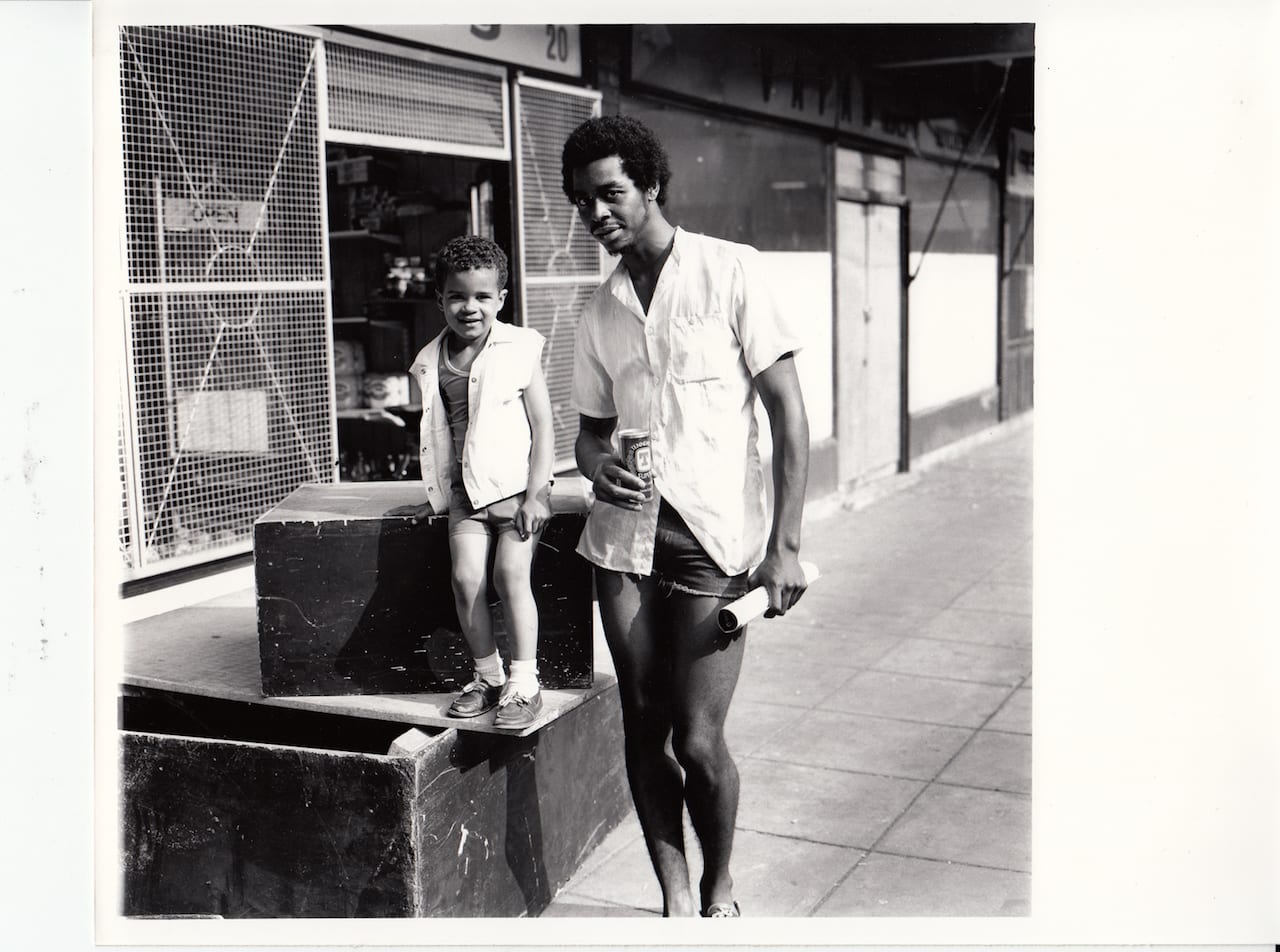

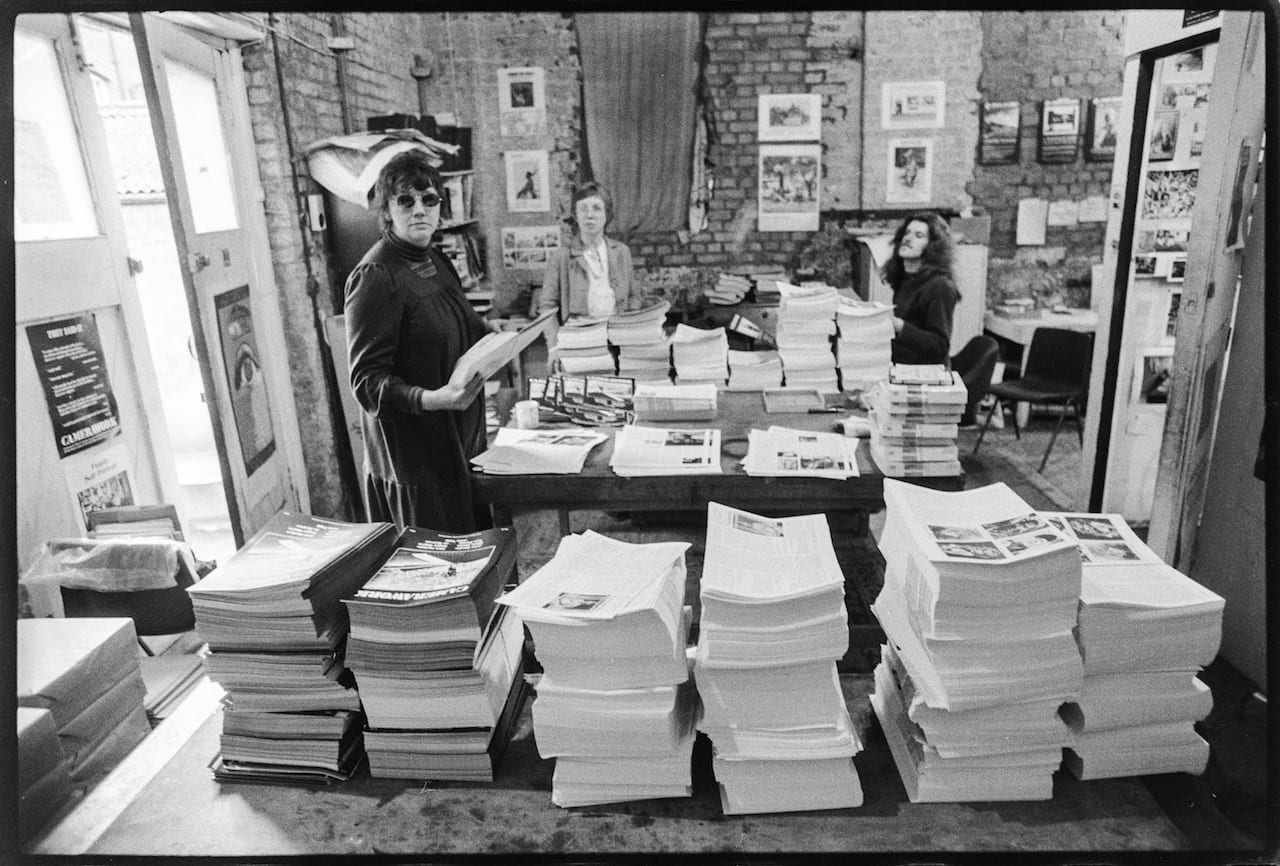

Whether it was running as Half Moon or Camerawork, the collective’s aim was the same – to demystify the process of photography, and to use it as a tool for social change and political activism. The first issue of Camerawork was themed The Politics of Photography, and used stark black-and-white litho print on a broadsheet format (sheets of A2 paper folded to A3, then to A4). It was pulled together over an all-night session fuelled by bagels and coffee at Half Moon’s first studio in Chalk Farm, and sold for 20p per copy.

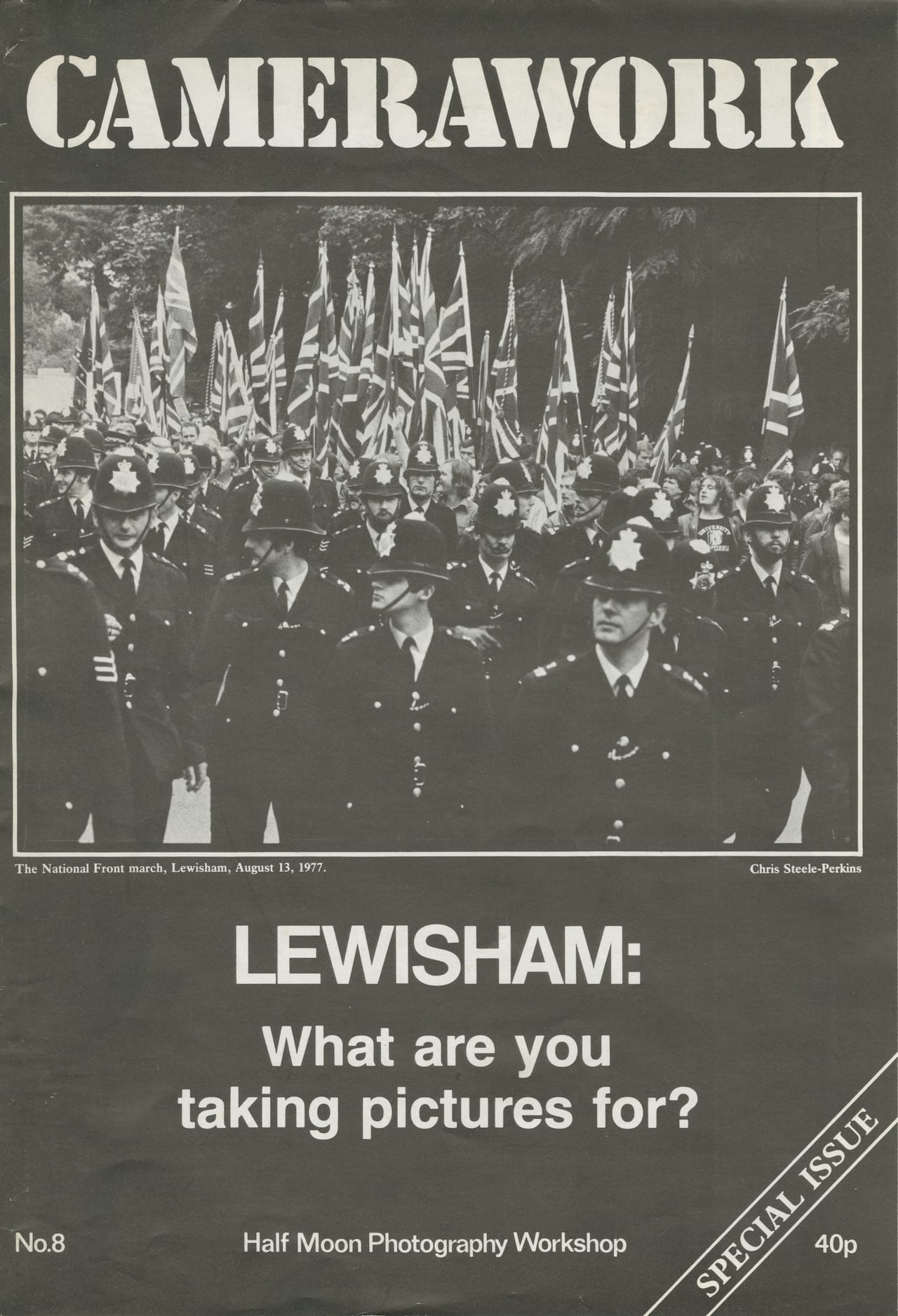

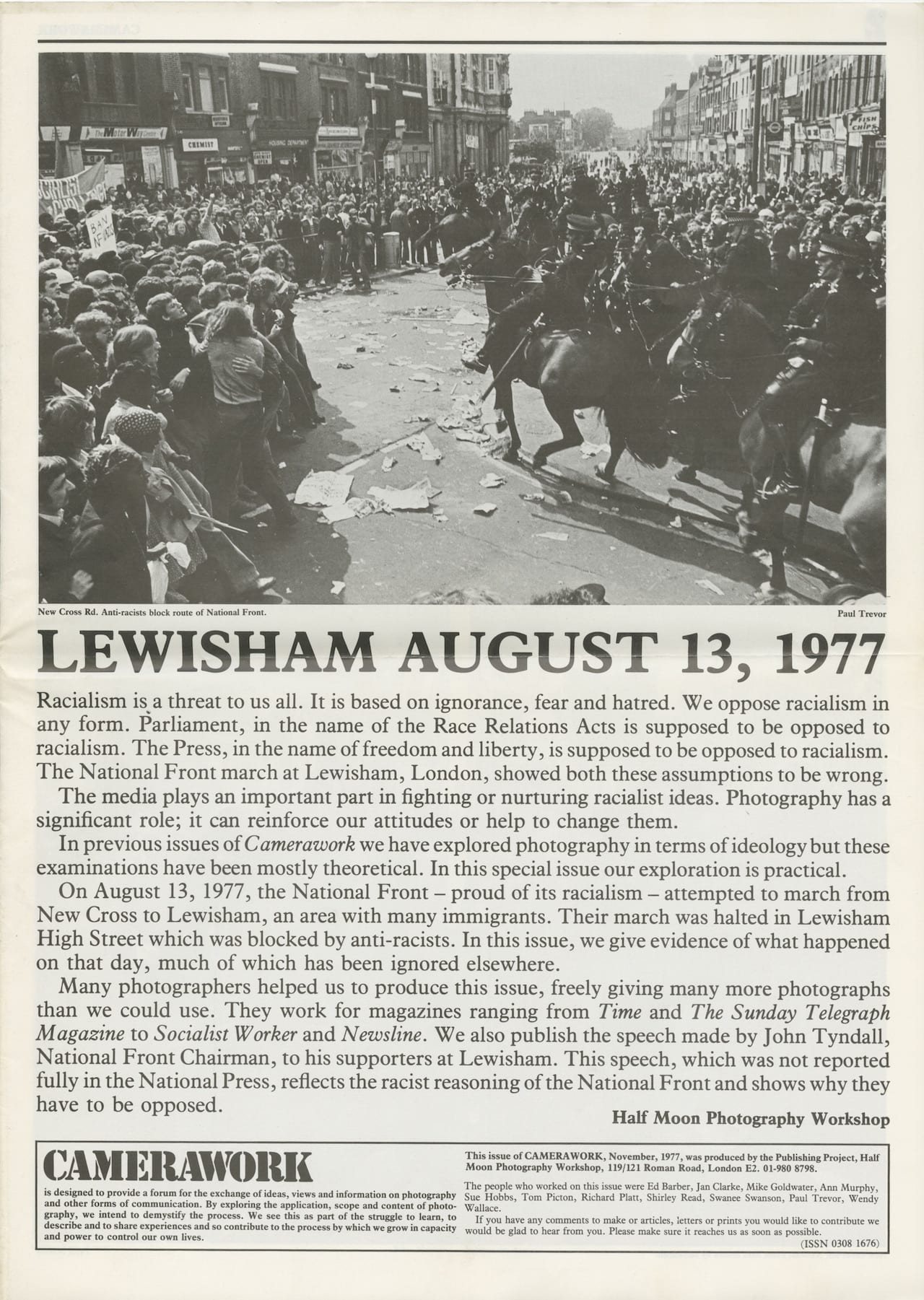

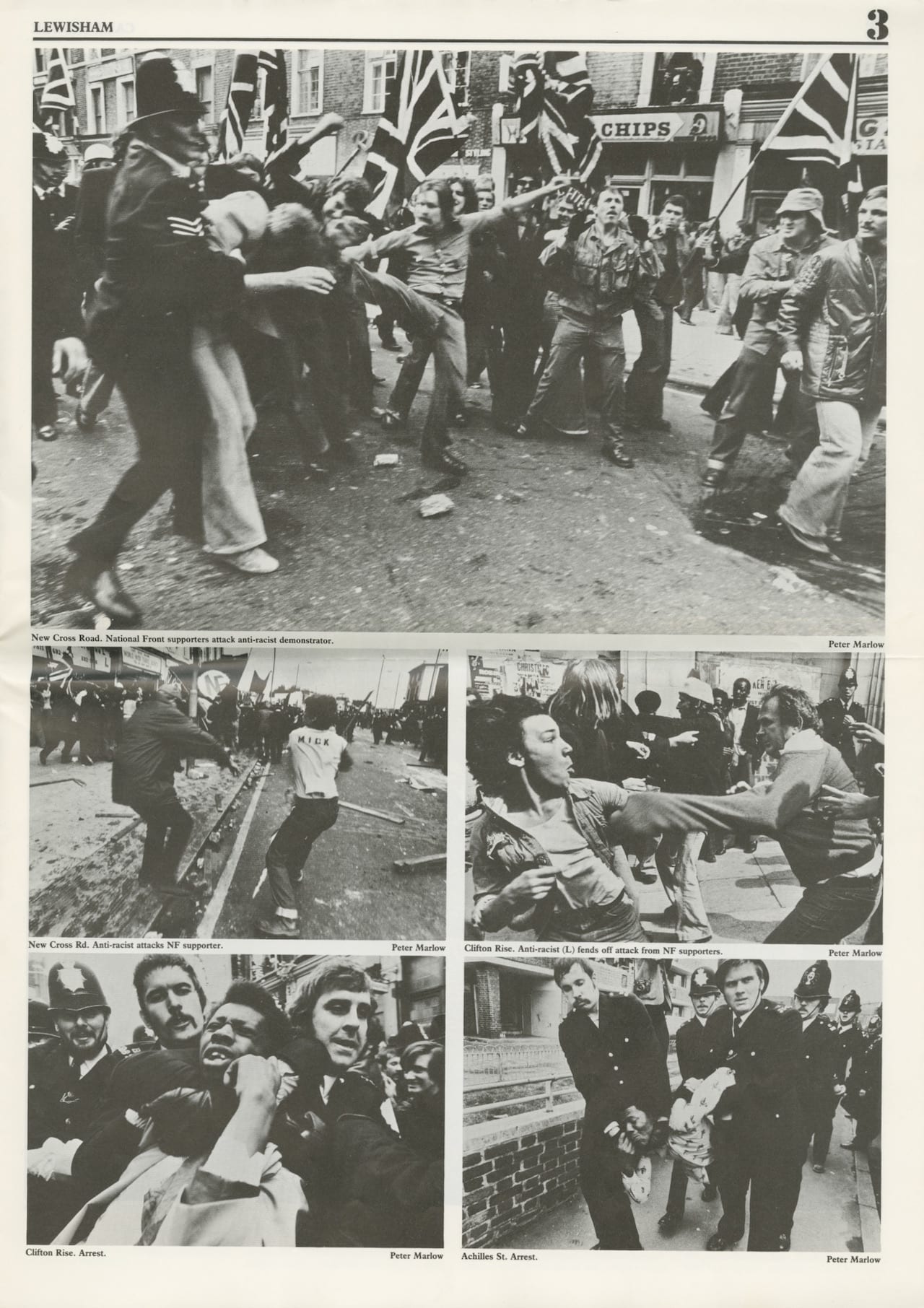

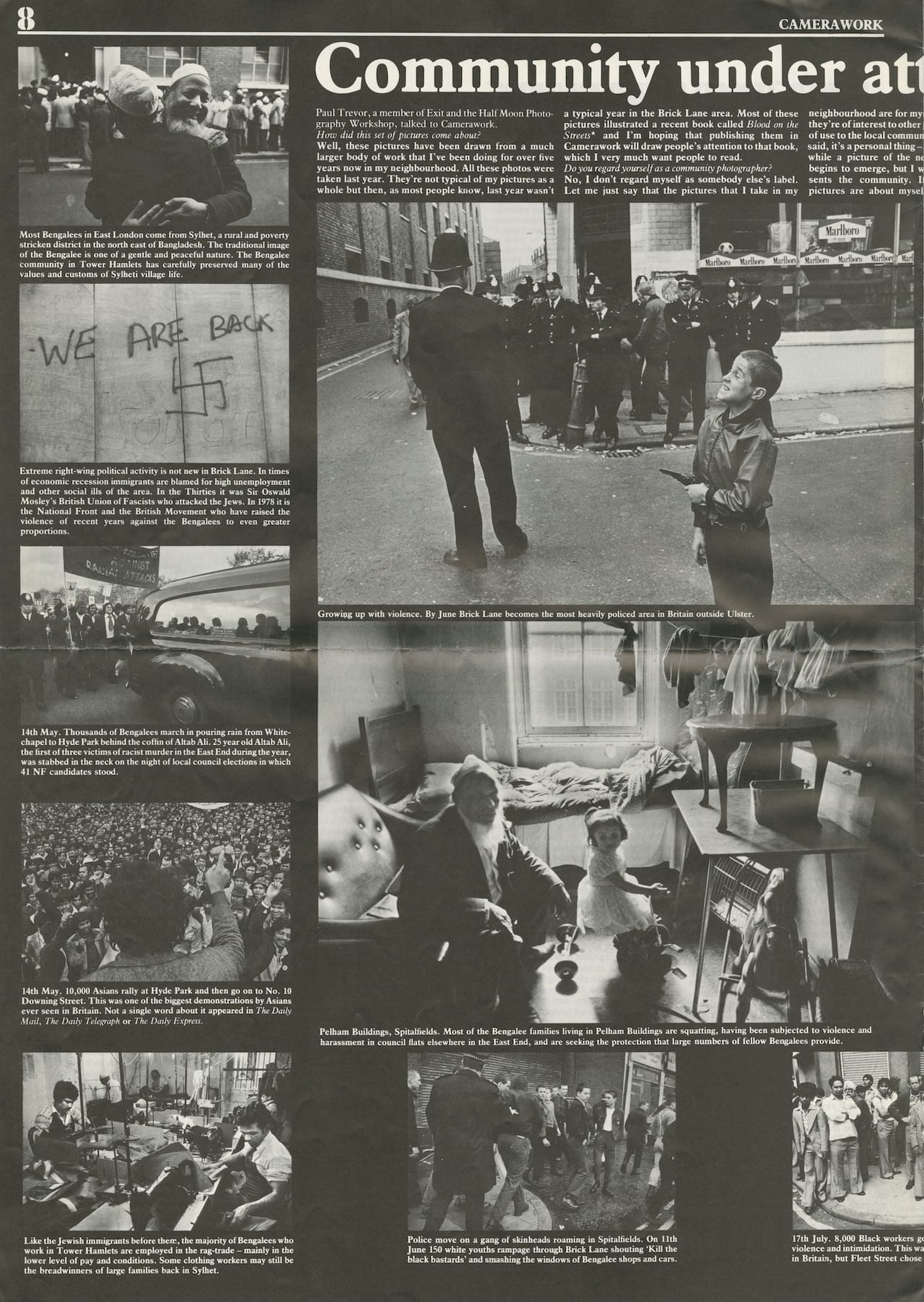

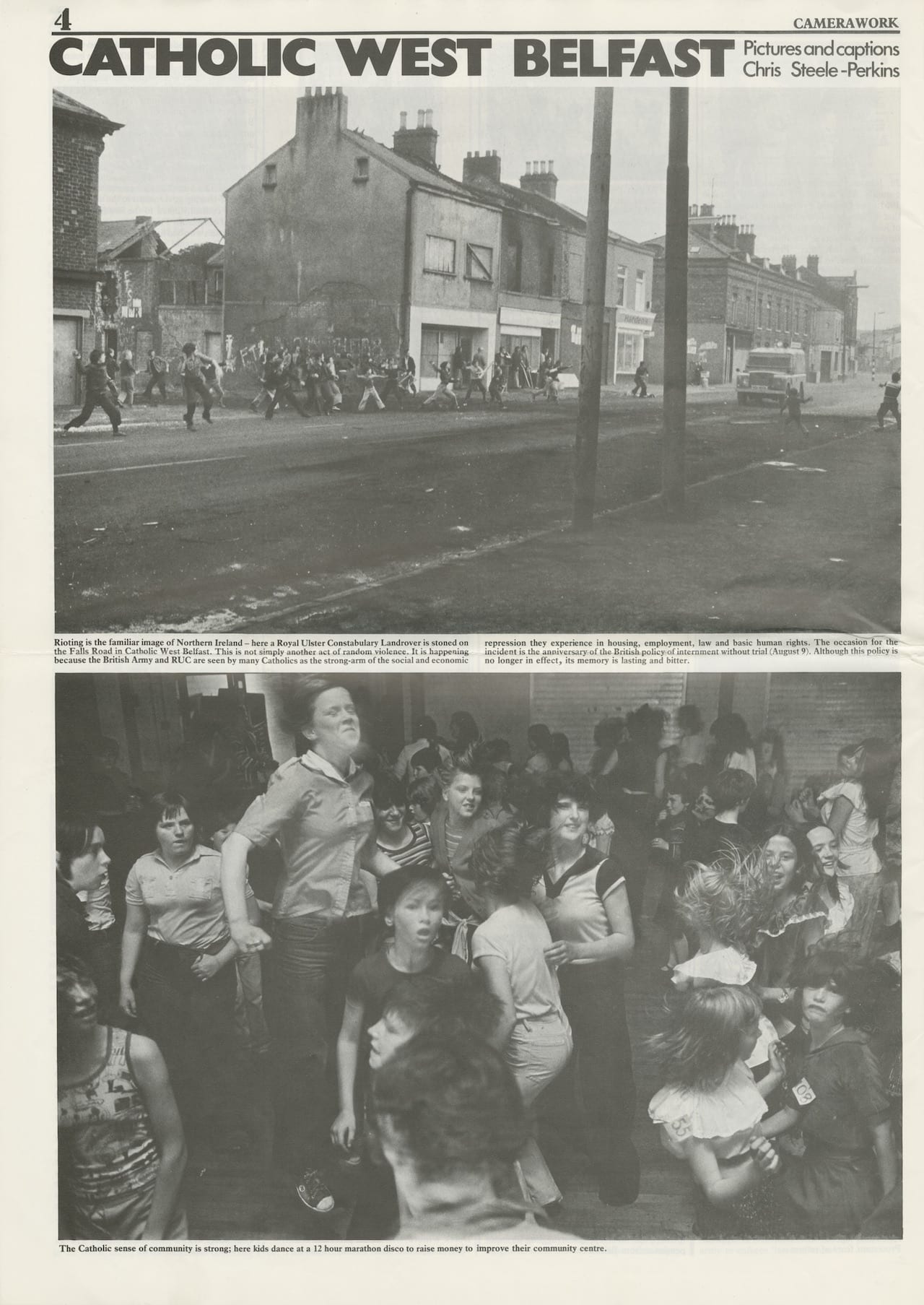

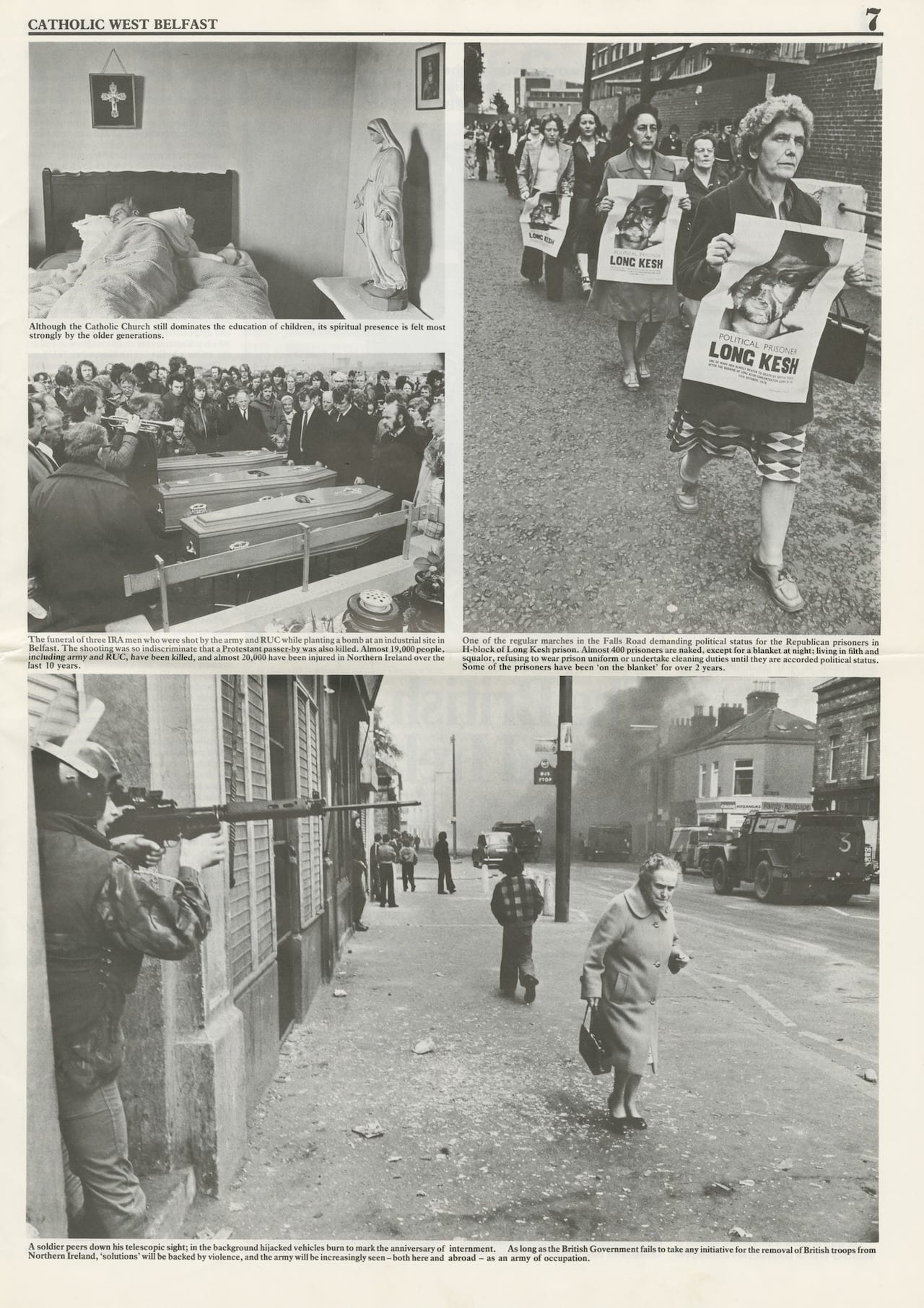

Each issue of the magazine was themed, and used photography as a gateway to discussing important political events. This included an issue on the Battle of Lewisham in 1977, in which anti-fascist protesters fought the far-right National Front, and another on the Troubles in Northern Ireland, which proved to be highly contentious during a time of severe press censorship, sparking the attention of the Home Office.

“All the theoretical ideas led to methods of making photographs that were primarily concerned with communicating the subject in the strongest and most accessible way,” says Kennard. “Theory and practice were intertwined, one fed the other.”

Among the collective’s early practitioners were Paul Trevor, Mike Goldwater, Janet Goldberger and Tony Bock, who were later joined by key figures like Ed Barber, Shirley Read, and Jenny Matthews, who introduced Kennard to the group in 1976.

Trained as a painter, Kennard made the move to photography in 1968 following the anti-Vietnam War protests, in the search of a new form of expression that could bring art and politics together. In 1976, he held his first exhibition, Document on Chile, at Half Moon Photography Workshop, which was then based in Alie Street, East London.

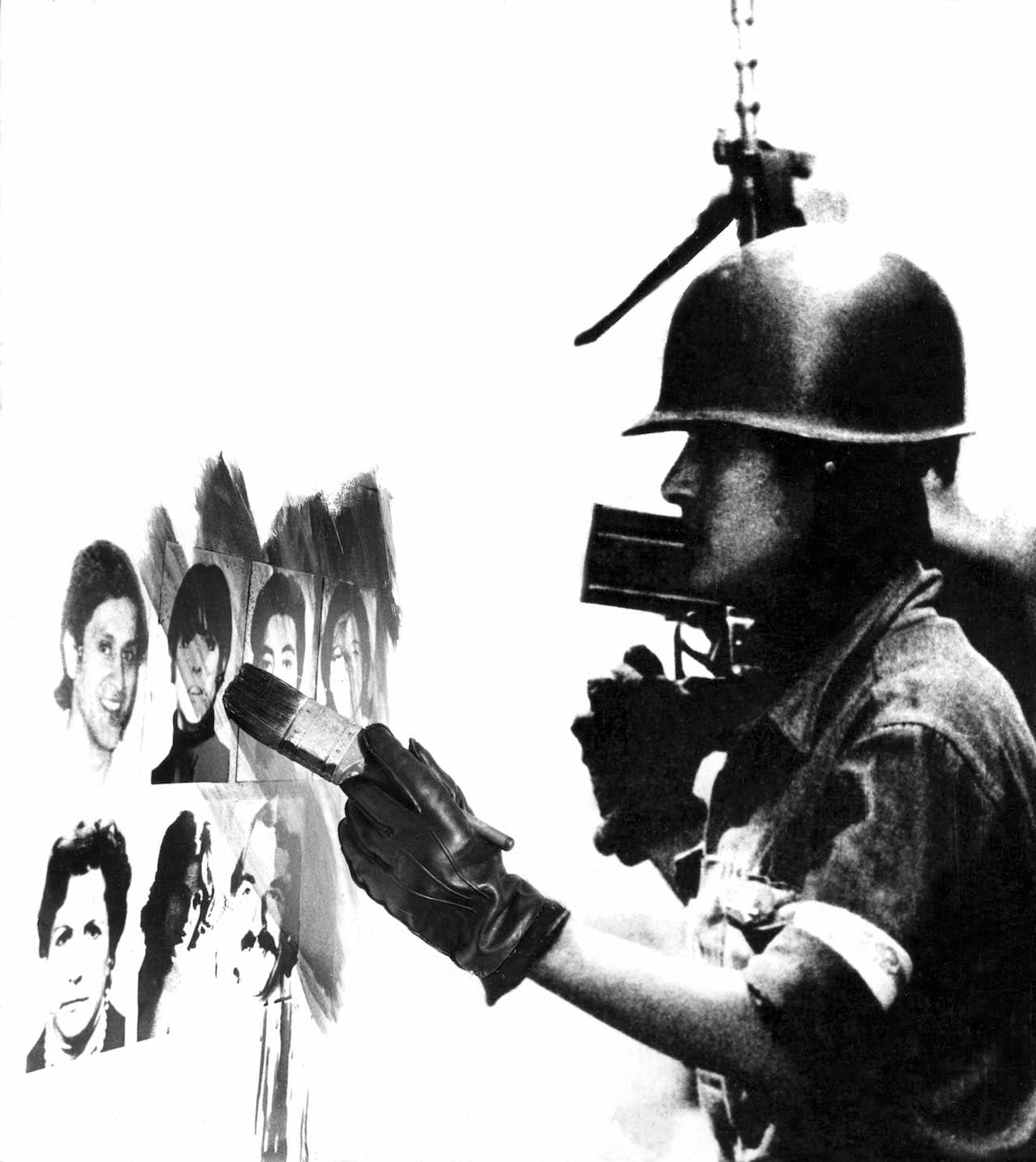

Kennard’s work was accompanied by the writing of Ric Sissons, and focused on the history of Chile and the 1973 Pinochet coup. With help from Amnesty International, Kennard was able to obtain photographs of prisoners who had mysteriously disappeared, which he used in a photomontage showing a soldier painting over their faces. The image was then used by Amnesty in a fundraising poster, and also published in Camerawork.

The exhibition was Kennard’s first “laminated show”, an idea which Ed Barber came up with as a solution to protect the photographs from a leaking roof in the Alie Street gallery. They ended up touring these laminated photographs across the country, packing the A1 sheets into travelling boxes that would be pinned up in town halls, youth clubs, and at one point a launderette.

It was an effective way to get the work of young socially-conscious photographers in front of a general audience, nationwide, and at a very low cost, says Kennard. “It devalued the photographs as objects, but it meant they could be sent and pinned up anywhere. They never seemed to get stolen or vandalised, even when they were put in places that weren’t invigilated.”

Kennard’s photomontages were often seen as posters on the street, on placards in protests, or in support of groups like the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. For Issue 19 of Camerawork, he put together a four page spread based on E.P. Thompson’s essay, The State of the Nation. It included his well-known appropriation of John Constable’s 1821 painting, The Hay Wain, with cruise missiles pasted into the landscape as a protest against the deployment of the missiles in Britain.

In 1977 Half Moon Photography Workshop moved to Roman Road, Bethnal Green, East London, and in 1981 the organisation took the name Camerawork – the same as its renowned magazine. But the intentions behind it began to change later in the 1980s, along with the concerns of many artists and photographers, moving away from social struggle and towards more academic debates about representation and popular culture.

“There was a lot of debate about how theoretical the magazine should be. There were people who were interested in the documentary stuff, and other people who were into the semiotics and theoretical side rather than communicating to a general audience,” says Kennard. Eventually, with a lack of funding and loss of organisational direction, the magazine folded after issue 32 in 1985.

Over the near-decade it ran, Camerawork made a profound impact on the debates in photography in the UK, and brought a breadth of political photojournalism to audiences across the nation. Even so, its influence remains under-appreciated – something that Four Corners hopes to change through its new digital archive and corresponding exhibition.

Radical Visions: The Early History of Four Corners and Camerawork 1972-1987 is open till 22 September at Four Corners in Bethnal Green, East London. https://fourcornersfilm.co.uk/

The full digital archive can be accessed at www.fourcornersarchive.org