“The thing is we are living in a fast-forward media world right now,” says Jan Grarup. “So what is considered a sexy conflict now is completely irrelevant in two days’ time, because something else will have come up. We are eating these conflicts, we’re only chewing these conflicts when they’re sexy, when the media thinks they can make a headline for a couple of days. Then they’re just forgotten. I get really frustrated about that.

“There are more than 20 forgotten conflicts around the world right now, and many of them could be stopped quite effectively if we – and by we I mean the West and the UN Security Council – took on the responsibility,” adds the Danish photographer, who has visited both well-known areas of conflict such as Iraq and Iran, and overlooked regions including Darfur, the Central African Republic and Somalia.

In fact he’s been photographing conflict since the 1990s, witnessing the devastation of the Rwandan genocide first-hand early on in his career. It’s an experience that never left him, and which led to him being diagnosed with PTSD, but he’s determined not to look away – instead resolving to help other people appreciate the severity of these conflicts, and their own culpability.

“I do believe that with the wealth and the ability to build the societies we have [in the West] comes a real responsibility,” he says. “In order for us to live in the society that we want, with free trade agreements or fewer wars, we have a responsibility. If you look at the African continent again with all the former colonies, how the countries are all mixed up, or even in Syria and the Middle East where countries have been affected [by Western intervention], we have a responsibility.”

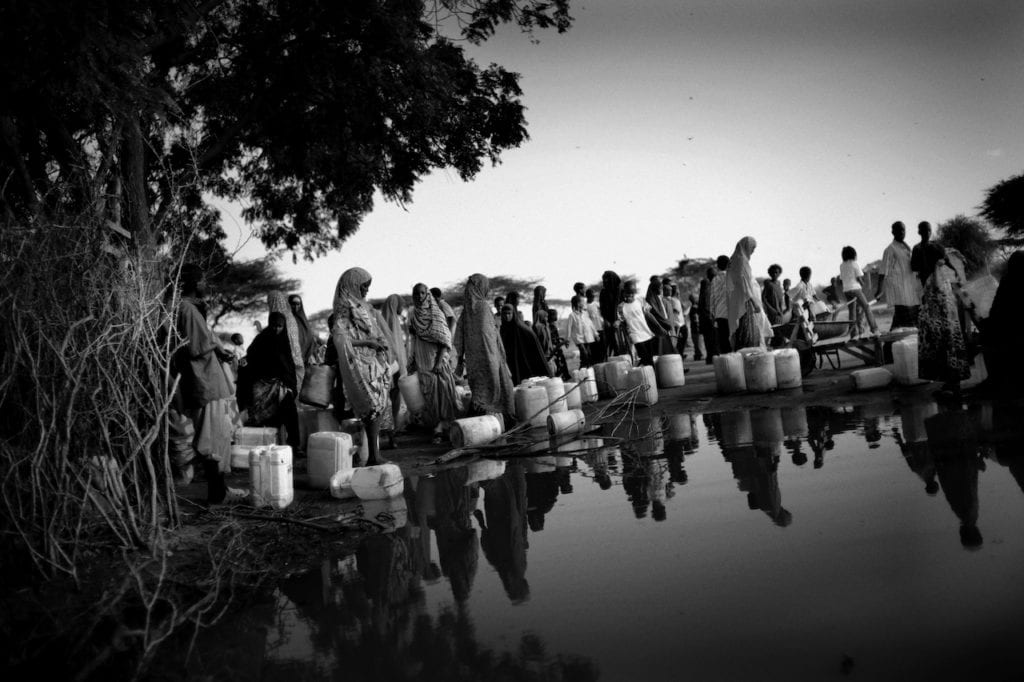

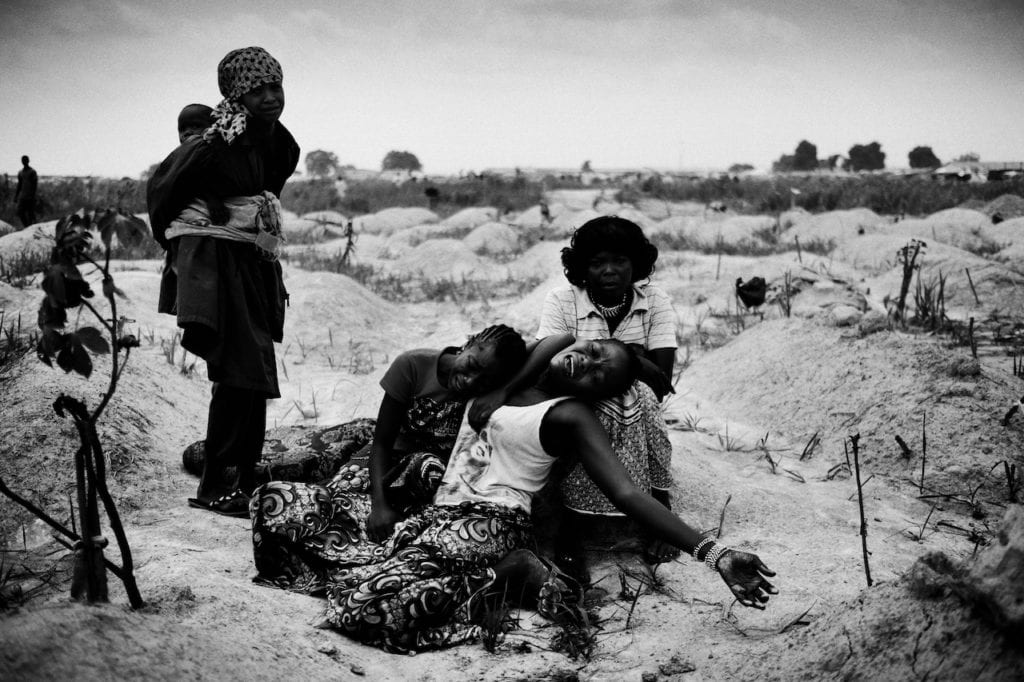

The images are shot in stark black-and-white, another choice which Grarup hopes will command attention from an audience often keen to look away. “Black and white distinguishes itself from the fast-forward news picture which means that people will come at it with another perspective and another eye. So they will say, ‘Why is this different?’ They will stop and think and take it further into their consideration,” he says.

“Some of the people that I admire the most photography-wise are people like Eugene Smith and Sebastiao Salgado, because they also have this ability to use the aesthetics and see things from a different perspective in a serious story.”

Building these perspectives takes time, and Grarup avoids being airlifted in and out of stories. He worked in Sudan over six years and in Somalia for four; in the past ten months, he has visited Mosul eight times, and plans to return before the year is out. “I would get people to trust me just by spending time,” he says. “From my point of view, there are three things which are really important in terms of photojournalism.

“First is dedicating the time it needs for people to get used to you. Second, it’s to have an honest and solid interest in these people and their lives, being there for a reason which is that you want to know about them. Third, once people realise that you really want to know more about their lives, they will let you in. It’s different from fast-forward news. You cannot go shoot in Syria for four days. It takes four days just to get acquainted with a place, before you can start working.

In doing so, he says, he’s able to find stories beyond the headlines – often ones that present a more hopeful perspective, even in the midst of disaster. “I spent four years on and off in Somalia, I covered the conflict with the Al-Shabaab militias and the radical Islamism and the warlords and the radical Muslims invading the country. But I also covered a story about young girls who were defying all this and playing basketball,” he explains.

“They were becoming a symbol of a young generation of women growing up in Somalia with a lot of pride but also redefining a gender equality issue. People just love those stories: there were so many people and so many women around the world who reacted to that story, asking how they could support it or be involved.

“Children have the most amazing ability to adapt and adjust and survive in any conflict in the world and I am blown away by it constantly,” he continues. “I have met children who have been assaulted in Central Africa by militias. Three days later they’re able to smile because they’ve found something to play with. How on earth is this possible?

“The last picture in the book is this boy swinging on an electric wire just outside of Mosul as the fighting is still going on. I’m in my flat jacket and my helmet; what he sees is an electric wire that’s fallen down and he thinks here is a great swing, let’s go play on it. It’s amazing.”

“There’s a reason that so many Syrians started to flood into Europe and it’s because the neighbouring countries there are full up with refugees,” he says. “It’s beyond what Turkey or Jordan or Lebanon can actually take. Every fourth person in Lebanon is a refugee. Can you imagine that in a European country?

“There was a report from the UN stating that by 2050 there will be more than 50 million climate-related refugees trying to leave Africa. Not war-related, just climate-related. Maybe we should start looking into that now before it’s too late, because these 50 million people will at some point try to get here. Maybe we should try to get involved not just when there is conflict, but in helping the entire global situation and deal with it beforehand.

“I’m not saying that we should just open up our borders and let in refugees endlessly. I’m saying we need to find and plan for solutions which go longer term and we need that now. Maybe we should start stabilising the Northern part of Africa. If you could stabilise that many more people would stay there before leaving. Most of the people I meet just want to go home, most of them just want to stay behind. But they can’t.”

It’s a message that’s arguably more important than ever right now, as migrant numbers build but Western political attitudes towards them harden. But for Grarup, it’s not just a question of taking pity on the people he photographs. It’s also a question of considering what we in the West could learn from them.

“I meet people with more empathy and more care towards one another in war situations or in conflict around the world than I have ever experienced in Europe,” he says. “People want to share the little they have with me because I have talked to them and shown an interest in them.”

And Then There Was Silence by Jan Grarup is published by BookLab, RRP £45