“MY FRIENDS!” writes Çağdaş Erdoğan from the Silivri Prison, Istanbul on 21 September, in a handwritten letter translated by a curator contact and circulated by his publisher Akina Books. “I salute all of you with my heart. Regardless of the illogical times we have been having, I hope you are well. Don’t worry about me. I’m doing well despite the physical and psychological negativities I experienced since the last two weeks.”

Erdoğan was taken into custody at the start of September and officially arrested on 13 September, when he was put into pretrial arrest on accusations of membership to a terrorist organisation. In his letter, Erdoğan discusses the reason he was initially apprehended, and discusses some of the reasons he has been given for the terrorism charges.

“My friends, I’d like to mention the ‘candid camera’ you all know of by now, on the second day of Eid on 2nd of September in Yoğurtçu Park where I had gone to have a break,” he writes. “I was taken into custody in the park because I was taking pictures of an ‘invisible’ building which belongs to the state. Nevertheless, I was not able to see any building, only birds and trees when I was taking pictures.

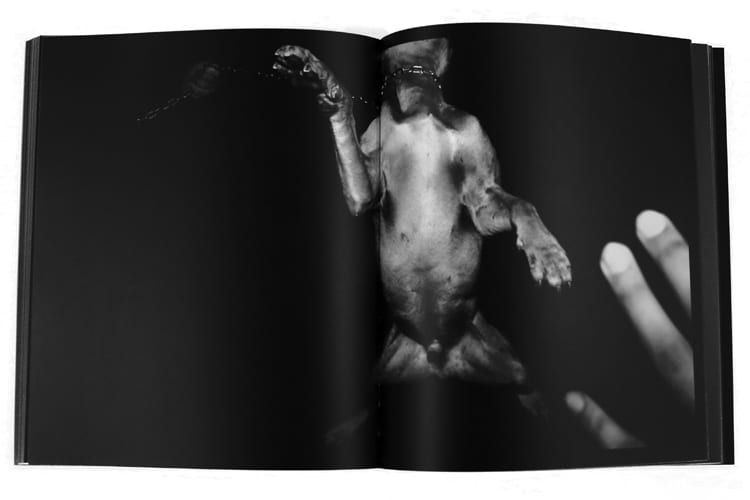

“I learnt the actual reason of why I was taken into custody when they took me to the police station. The pictures I have been taking for international newspapers and magazines constitute a crime. The pictures, which have been published primarily on The New York Times, The Guardian and BBC, are treated as in scope of ‘’conducting activities in the name of a terrorist organisation’’. Moreover, the prosecutor presented my photos of dog fights that are in my book Control, as evidence of charges on ‘PKK membership’!

“I have been aware that I could get charged by compelling accusations. And this is what happened. After the quarantine and detention room that took 13 days, I got detained with a jet-fast courthouse decision. I have been accused officially that I was ‘a suspect of a terrorist group member’’; like The New York Times, The Guardian, BBC and other terrorist groups?”

“Turkey, which is ranked 155th out of 180 countries in Reporters Sans Frontiers’ 2017 World Press Freedom Index, is now the world’s biggest prison for professional journalists, with more than 100 detained,” RSF states. “More than 150 media outlets have been closed without reference to the courts. They have been closed by decrees issued under the state of emergency. Media pluralism has been reduced to a handful of low-circulation newspapers.”

According to the Stockholm Center for Freedom, as of 26 September there were 256 journalists in jail in the country, of whom only 25 had been convicted. A further 135 journalists were wanted by the Turkish authorities. Back in May this year, French photographer Mathias Depardon hit the headlines after being detained by the police in Turkey for a month.

Despite this gloomy backdrop to his current predicament, Erdoğan’s letter remains optimistic, ending on a positive note. “My friends, my dears!” he ends. “Believe me I’m more hopeful than I have ever been. I keep my belief that there will come the days when we hug each other without any wars when these insane days are over. You should keep your belief as well.

“Whenever you feel suffocated, remember Berkin, Nuh Köklü, Hrant, Taybet İnan. Hold on to each other better. Don’t forget that this country belongs to us, not to the ones who want to kill us! With the hope that we will see each other again on a sunny spring day…”

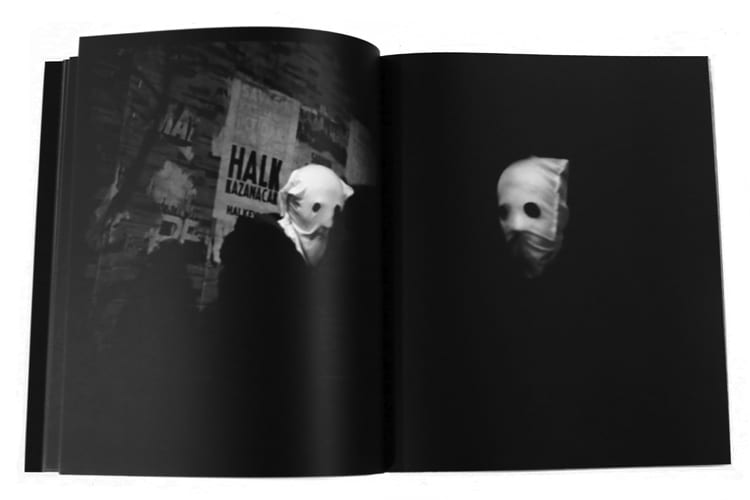

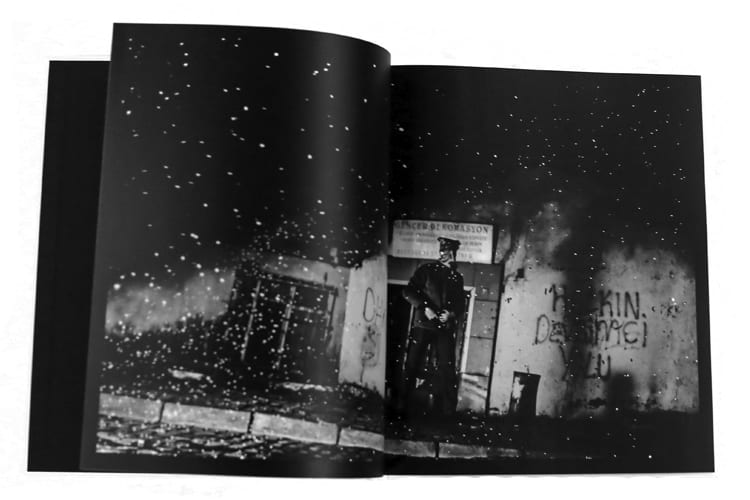

Erdoğan works as a photojournalist, but also makes personal projects in which he often portrays hidden aspects of life in Turkey, such as nightlife, the lives of LGBT communities, and resistance movements. Earlier this year, he published his first monograph with Akina Books – Control, which was shot in Istanbul from 2015-17. He was one of BJP‘s Ones to Watch earlier this year.