Few countries have experienced as rapid a transformation as Japan during the 20th century. Once a closed country with extremely limited interaction with the outside world, it opened its borders to become a pioneer in many fields – including photobooks. Now a new compendium, The Japanese Photobook, 1912-1990, brings together some of the most important publications, a mammoth endeavour that took editor Manfred Heiting six years.

“It is in photobooks we saw the 20th century unfolding,” he says. “This is not a selection ‘best of’ or ‘the most valuable’ of photo books. It is intended to show the development of the Japanese photobooks and publishing, how it relates to the cultural development of the country, how it captured its most important historic events – and including all the book details – and differences in publishing.”

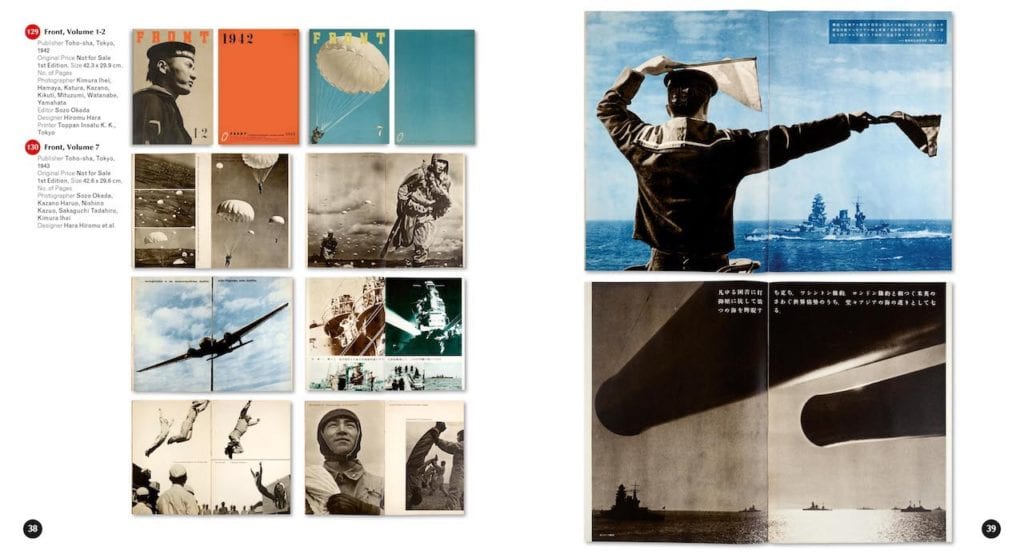

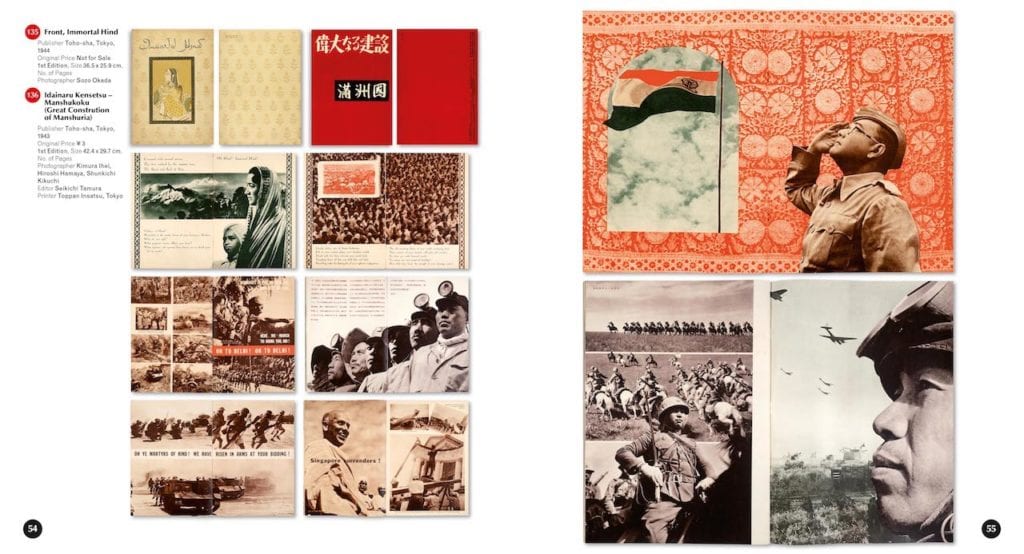

Together the photobooks depict how Japan adopted and adapted external influences into its daily life, but also the ongoing influence of Japanese culture. First used extensively by the military and brought into the public sphere with the photobook showing the funeral of the Meiji Emperor in 1912, Japanese photobooks have been a source of photographic inspiration around the world, particularly in the mid-20th century.

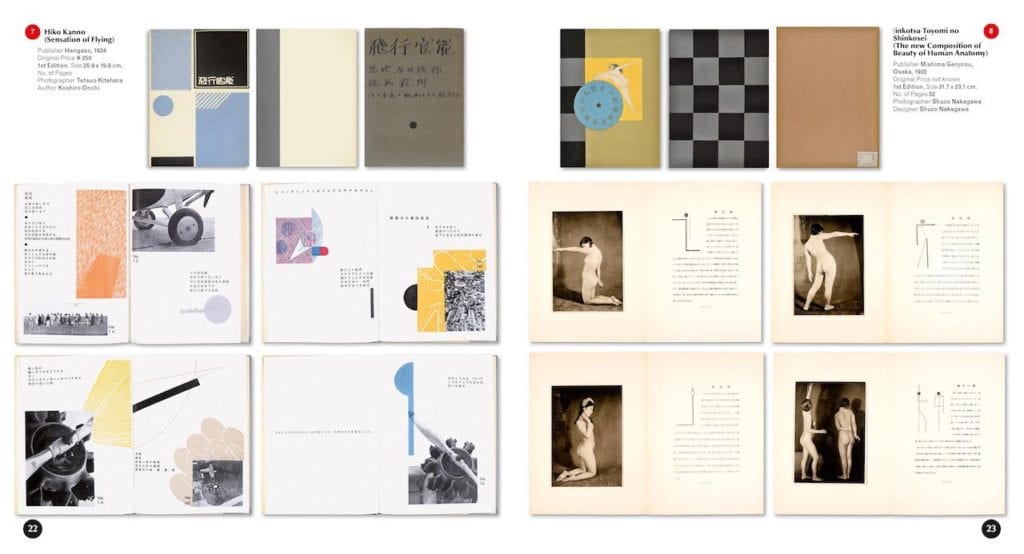

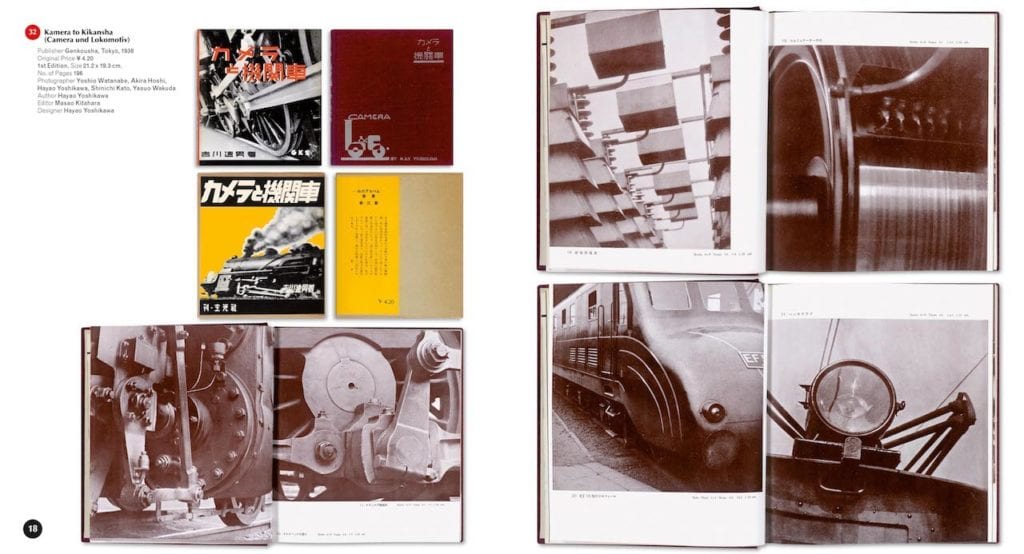

“Photography came late to Japan – and all ‘raw materials’ needed to be imported,” says Heiting. “When the few Japanese photographers and architects returned from studying at the Bauhaus, they brought those ideas home. These photographers adopted many ideas and started making some very interesting photobooks.”

As a key form of artistic expression in the region, Japanese photographers and publishers quickly used photobooks as a propaganda tool, and to document the changes in the country. When World War Two was over, the photobooks took on a different relevance as a means of social expression, depicting the mood and political situations in flux. An extended period of unrest provided fertile ground for young photographers to really experiment, while documenting what was going on in their country – particularly those involved with the Provoke magazine published on 1 November 1968, and 10 March and 10 August 1969.

“There was Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the American occupation, but also the uprising of students and farmers against the seizure of land for Narita Airport. It all unleashed the desire of the young generation to say that they had enough,” explains Heiting.

“The Provoke and protest publications are the most important Japanese contribution to photography and photobooks and photo magazines worldwide. The photobooks after the 1950s demonstrate a very unique Japanese identity to us.”

Unfortunately, Heiting sees the gradual demise of the artistic potential of the Japanese photobook starting with John Szarkowski’s exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1974. It was there that he told the show’s co-curator, Yamagishi Shoji, that “good photographs need to have a white border”. Ultimately, this led to a homogenisation: “That killed the uniqueness of Japanese photobooks. They all began to look like the ones in the West,” concludes Heiting.

The Japanese Photobook, 1912-1990, is published by Steidl, €125