Seven years ago, Harit Srikhao, then just a schoolboy, spent the night at a friend’s house as violent clashes broke out between protestors and the military in Thailand. He cursed the protestors and watched them being beaten on the news with some satisfaction. In the following days and weeks, he participated in clean-ups on the streets with his family.

It took years for Srikhao to question what had happened that night, and the chain of events which had culminated in the violence. He now tries to represent the law and politics of his country through photography, and hopes that his series Whitewash will help other people in Thailand start to ask the same questions. BJP spoke to Srikhao shortly after he was shortlisted for the undergraduate series section of this year’s Breakthrough Awards – at a time when Whitewash has come under fire in exhibitions back home.

Harit Srikhao: 2010 was a time when political demonstrations were continually breaking out. On the evening of the 28 April, there was a clash between protesters and troops that prevented me from going home from school. As a result, it made me hesitantly take a long, fearful walk to my friend’s house. It was the safest place I could get to that riotous night. It felt like a bad dream, however to stay at a friend’s house without parents was like an amazing summer for us back then. After that, I shot my first series, Red Dream (2012), by returning to photograph the routes that I got lost in on the night of the military crackdown.

BJP: What inspired you to create Whitewash?

HS: In 2013 – 2014, there was a demonstration organised by the political pressure group, the PDRC [People’s Democratic Reform Committee] that paved the way for the Royal Thai Armed Forces to launch a coup d’état on 22 May 2014 – the 13th coup d’état in Thailand. This provoked me to ask questions and become more curious about politics. I researched my country’s history and found all the stories I used to know and believe were one-sided. It changed my political views and made me see differently forever. Thus, the beginning of this work was to painfully question myself: “For four years, why have I been unaware of hundreds of people’s death caused since the military crackdown in 2010?”

BJP: Do you think these photographs can help to shape the narrative about the political situation in Thailand?

HS: In Thailand, the artworks supported by the government are total propaganda, especially photographs. Instead of representing democratic and scientific thoughts, those photographs work in a ritualistic way and have become icons in themselves. This phenomenon can be seen through portraits of the crown appearing all around the country. Thus, most art in Thailand still concurs with the authoritarians’ ideas, instead of posing a question to find the truth. As a result, I expect that my work would be one of a minor historical record from a grassroots view, striking back against the fabricated tales of the government. In the future, if people come to investigate this period of time, they will know there were a few people talking differently from the government.

HS: Thailand has suffered from propaganda for a long time. There is no doubt that Thais would not listen to what foreigners say about the situation in the country. My hope is for change from a new generation in the world of a borderless internet. This generation, unaffected by the notion of a nation state, would realise the truth – that there is no angel or evil in this world. We all are Human.

BJP: Did you at all feel in danger whilst taking the photographs?

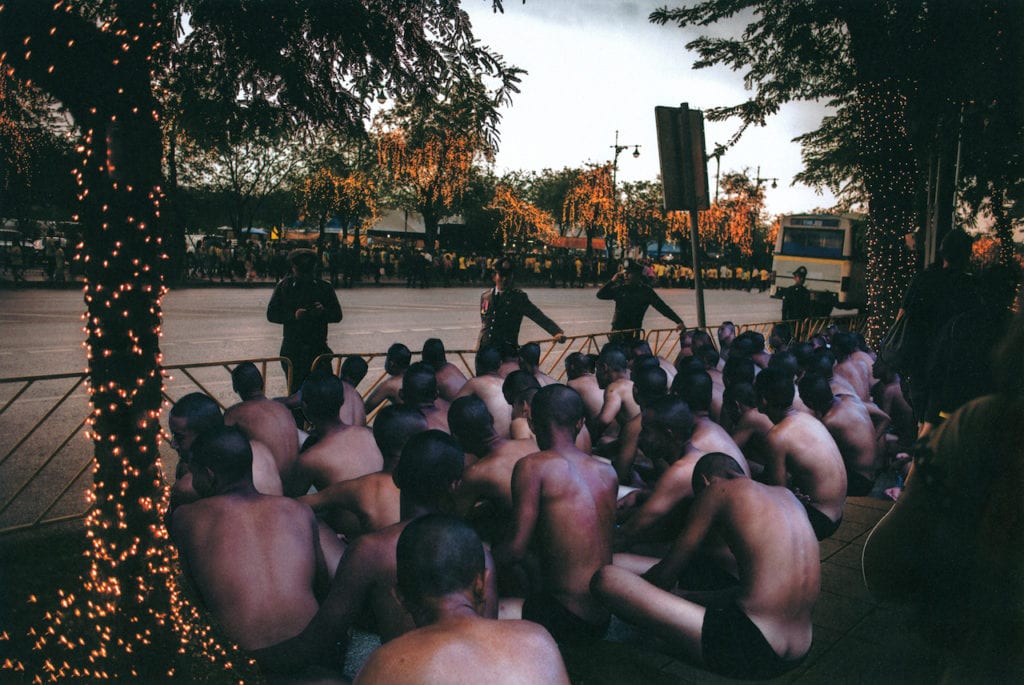

HS: Although the subjects being photographed in my work were on the opposite side to me, for example, cadets, scouts, government officers or even politically naive young men, they were really nice to me. Moreover, I could feel lots of energy breaking out in their bodies. Unfortunately, they were oblivious as to the use of that power and energy in some ways. However, I do still have hope that one day these people will become aware of the power inside of them and creatively use it to make a worthwhile change.

BJP: Should the photographs make people question the reality they see around them?

HS: [In my work] I believe in an ability and a possibility to deal with the truth, or even to construct alternative truths. I’m not talking about running away from the reality, I’m talking about looking at the truth in a different way. Personally, the truth is always subjective.

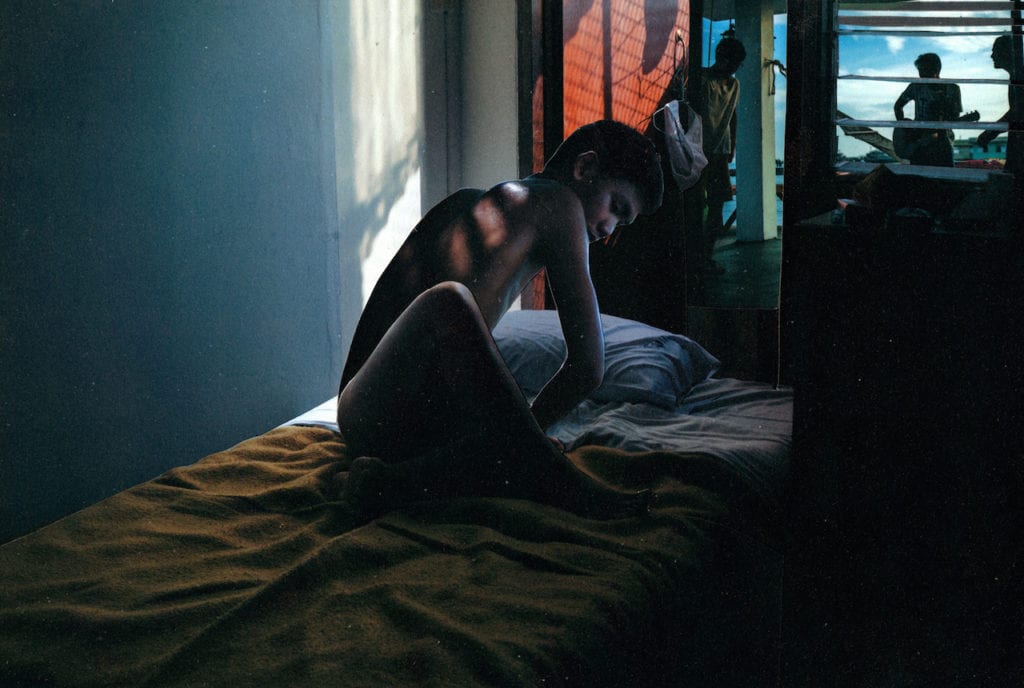

HS: For me, “whitewash” refers to the act of suppressing all guilt in the name of historical purification, and the suppression of memories, bodies, desires and dreams of people in the nation. Also, the propaganda which distorts facts in order to determine ultimate control over the lives of the people.

BJP: How do you make your images?

HS: I started with a documentary approach, returning to the places where I was experiencing the uprising in 2010 and photographing them. Then, I edited those photos through collage techniques. I felt this reflected how I wanted to talk about a surgery, cutting the paper. I chose to use a paper cutter instead of using Photoshop as it left scratches and clues that I needed.

After I finished cutting them, I started to experiment with other techniques, in order to put the effect into them. Then, I chose some proper methods that provided visuals that were interesting enough to provide a thematic motif for this work.

BJP: The visual elements have an ethereal effect. Does this make the photographs more distant?

HS: I want my work to have dreamy atmospheres, like a world which falls into a trance, like it is being hypnotised.

HS: The military crackdown on 19 May 2010 ended up in dozens of people’s deaths, the highest numbers in the modern history of Thailand. A few days after that, groups of the middle class who supported the government – including my family and I – joined a ‘Big Cleaning Day’ activity arranged by the authorities. The purpose was gathering people and letting them clean the area. I still remember an atmosphere of that day clearly – the street was full of celebrities, singers, and pressmen, they all were having fun, giving out snacks and laughing as if they were in a celebration. I didn’t think anything of it at that time, as I didn’t know what had really happened there. However, that day now makes my hair stand on end, because I only realised the truth four years later.

BJP: What has been your experience of showing the work in Thailand?

HS: I exhibited this work from June-July at Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Gallery VER in Bangkok, but, just a few days after the opening, soldiers entered the gallery and removed some of the photographs.

BJP: Is politics still a very private matter in Thailand? Something not publicly discussed?

HS: Let’s say that you are able to talk about politics in public, but if you talk ‘bluntly’, you would be arrested; moreover, your friends and family would also be menaced.

https://www.haritsrikhao.com/ Harit Srikhao is publishing a book of this project with Akina Books, which will launch at the Unseen Amsterdam in September https://akinabooks.com