Brexit and the election of Donald Trump have brought national borders back into question after a period in which seemed that budget airlines and freedom of movement might make those red lines in the atlas less relevant. Sensing these geopolitical shockwaves, many photographers have produced photographic dispatches from contested regions where national and ethnic allegiances are once again coming to the fore.

But Jens Olof Lasthein, a Swedish-born photographer brought up in Denmark, has spent much of his career travelling around the European hinterlands, where international boundaries have been shifting for centuries. His new book, Meanwhile Across the Mountain, published by Max Ström, is a stunning survey of the Caucasus – the part of southeastern Europe that used to belong to the Soviet Union, but is now a collection of sovereign states and breakaway regions such as South Ossetia, Dagestan and Chechnya.

Lasthein’s photographs from these mountainous countries were taken over six years of repeated visits. The 90 beguiling images in this book are testament to his affection for the dramatic and misunderstood territory where history always seems to be in flux. “I don’t speak the Caucasian languages and my Russian is limited so there’s a great deal I don’t understand,” he says. “Even so, I feel it’s right to tell my story. The Caucasus has a very special place in my heart; I have always been made to feel at home there.”

Unty, Dagestan, 2015. From the book Meanwhile Across the Mountain © Jens Olof Lasthein

“More likely it serves the same need as going to the zoo: fascination of another world; unfathomable, unreachable and slightly titillating, beyond control. Naturally my view is also a Western one as I grew up and live in the West. But this view was challenged early on in my life, when I started travelling beyond the Iron Curtain, and got the intriguing feeling of both being at home and a stranger at the same time. This contradictory feeling has prevailed and proved to be a very good working condition.”

But Jens Olof Lasthein, a Swedish-born photographer brought up in Denmark, has spent much of his career travelling around the European hinterlands, where international boundaries have been shifting for centuries. His new book, Meanwhile Across the Mountain, published by Max Ström, is a stunning survey of the Caucasus – the part of southeastern Europe that used to belong to the Soviet Union, but is now a collection of sovereign states and breakaway regions such as South Ossetia, Dagestan and Chechnya.

Lasthein’s photographs from these mountainous countries were taken over six years of repeated visits. The 90 beguiling images in this book are testament to his affection for the dramatic and misunderstood territory where history always seems to be in flux. “I don’t speak the Caucasian languages and my Russian is limited so there’s a great deal I don’t understand,” he says. “Even so, I feel it’s right to tell my story. The Caucasus has a very special place in my heart; I have always been made to feel at home there.”

“More likely it serves the same need as going to the zoo: fascination of another world; unfathomable, unreachable and slightly titillating, beyond control. Naturally my view is also a Western one as I grew up and live in the West. But this view was challenged early on in my life, when I started travelling beyond the Iron Curtain, and got the intriguing feeling of both being at home and a stranger at the same time. This contradictory feeling has prevailed and proved to be a very good working condition.”

In the febrile new international era that Trump has instigated – and his shifting relationship with an old foe in Moscow – this corner of the world is once again taking on strategic importance. The accompanying crisis in what constitutes news, and whether we can trust the reporters and photographers who interpret these geopolitical issues, might seem debilitating to those working in the field, but Lasthein is confident that his craft still retains the ability to see through the fog of disinformation.

“I don’t suffer from the delusion that my story is the one and only true story,” he says. “An important factor for judging the quality of documentary photography is honesty: have the photographers been honest to their own experiences of the people they’ve met and their reality? It is not necessary or even desirable to simply transmit the voice of ‘the other’ but one needs to try to listen carefully and understand something beyond oneself to be able to shape it into a credible picture.

“My conception of the world is that it is full of contradictions and cannot be easily understood; that’s the adventure and joy of it. And that’s the reason we need different angles and approaches to get closer to some kind of truth.”

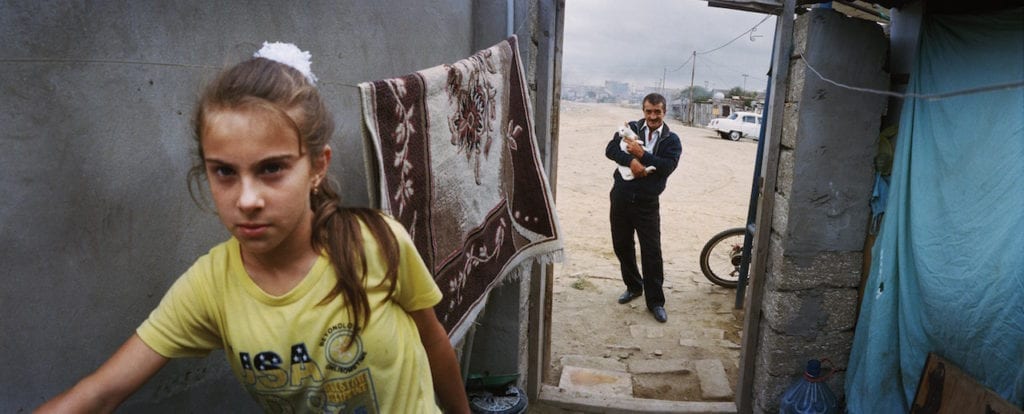

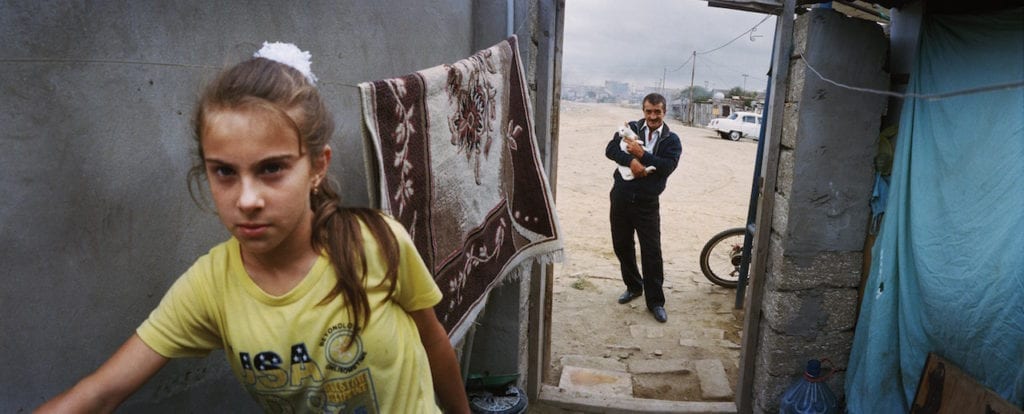

Pirallahi, Azerbaijan, 2014. From the book Meanwhile Across the Mountain © Jens Olof Lasthein

“When I found the panoramic camera in 1992, it was like finding my eyes,” he says. “Over the years I’ve tried to put it aside several times but it keeps coming back to me and now I’ve surrendered to it. The ultra-wide angle allows me to be in the middle of a situation and still get all of it into the frame.

“I enjoy the possibility of combining several actions in one frame, as well as being able to show both the action itself and a wider view of the stage where it takes place. The camera has many technical limitations, such as the curved lines deriving from the panning lens, but I’ve come to love them.”

After several decades in which the people of the Caucasus were seemingly united under Soviet hegemony, they are now jostling for newfound statehood with ethnic and religious differences once again marking friend from foe. Lasthein makes no attempt to intervene in these rivalries or mark out his photographs with too many signifiers of territorial dispute, but his opening texts give context to the territorial morass that often keeps these Caucasian people suspicious of their near neighbours, despite much shared cultural heritage.

Moody, atmospheric and replete with human curiosity, Meanwhile Across the Mountain is a personal account of a new world order manifesting itself only a few hours’ flight away from the UK.

lasthein.se Meanwhile Across the Mountain is published by Max Ström, priced £30. maxstrom.se This article was first published BJP’s July print issue, which can be bought via thebjpshop.com

Grozny, Chechnya, 2011. From the book Meanwhile Across the Mountain © Jens Olof Lasthein

Stepanakert, Nagorno-Karabakh 2014. From the book Meanwhile Across the Mountain © Jens Olof Lasthein

Ureki, Georgia, 2013. From the book Meanwhile Across the Mountain © Jens Olof Lasthein

Urus-Martan, Chechnya, 2011. From the book Meanwhile Across the Mountain © Jens Olof Lasthein

“I don’t suffer from the delusion that my story is the one and only true story,” he says. “An important factor for judging the quality of documentary photography is honesty: have the photographers been honest to their own experiences of the people they’ve met and their reality? It is not necessary or even desirable to simply transmit the voice of ‘the other’ but one needs to try to listen carefully and understand something beyond oneself to be able to shape it into a credible picture.

“My conception of the world is that it is full of contradictions and cannot be easily understood; that’s the adventure and joy of it. And that’s the reason we need different angles and approaches to get closer to some kind of truth.”

“When I found the panoramic camera in 1992, it was like finding my eyes,” he says. “Over the years I’ve tried to put it aside several times but it keeps coming back to me and now I’ve surrendered to it. The ultra-wide angle allows me to be in the middle of a situation and still get all of it into the frame.

“I enjoy the possibility of combining several actions in one frame, as well as being able to show both the action itself and a wider view of the stage where it takes place. The camera has many technical limitations, such as the curved lines deriving from the panning lens, but I’ve come to love them.”

After several decades in which the people of the Caucasus were seemingly united under Soviet hegemony, they are now jostling for newfound statehood with ethnic and religious differences once again marking friend from foe. Lasthein makes no attempt to intervene in these rivalries or mark out his photographs with too many signifiers of territorial dispute, but his opening texts give context to the territorial morass that often keeps these Caucasian people suspicious of their near neighbours, despite much shared cultural heritage.

Moody, atmospheric and replete with human curiosity, Meanwhile Across the Mountain is a personal account of a new world order manifesting itself only a few hours’ flight away from the UK.

lasthein.se Meanwhile Across the Mountain is published by Max Ström, priced £30. maxstrom.se This article was first published BJP’s July print issue, which can be bought via thebjpshop.com