As this suggests, Killip was scrupulous when he was shooting too, avoiding people who didn’t like to be photographed, or who didn’t want to be shown working, however informally, because they were collecting the dole [unemployment benefit]. And while he might not have known every individual he shot, Killip points out he spent years getting to know the area, living in Newcastle for 26 years (from 1975, when he won a two-year fellowship from Northern Arts to photograph North East England, until 1991, when he started teaching at Harvard).

He says he stayed because he liked it, and that he might never have left had the Harvard job not come along – but he was also inspired by the Magnum photographer Josef Koudelka, who came to visit him early on and “talked about the importance of being in one place, to get under the surface of things”. He was also interested in how differently Paul Strand and Manuel Alvarez Bravo photographed Mexico, he says, despite Strand’s sympathetic, card-carrying Communist credentials.

“Strand beautifies poverty and simplifies the Mexican people into ‘the poor Mexicans, but isn’t this wonderful visually’,” he says. “But Alvarez Bravo was Mexican, his pictures are very complicated because he was able to accept ambiguities and contradictions, which Strand couldn’t…I think because I lived in Newcastle for so long I was able to accept ambiguities and not worry about them, just accept them and show them. I wanted to be there and be more accepting.”

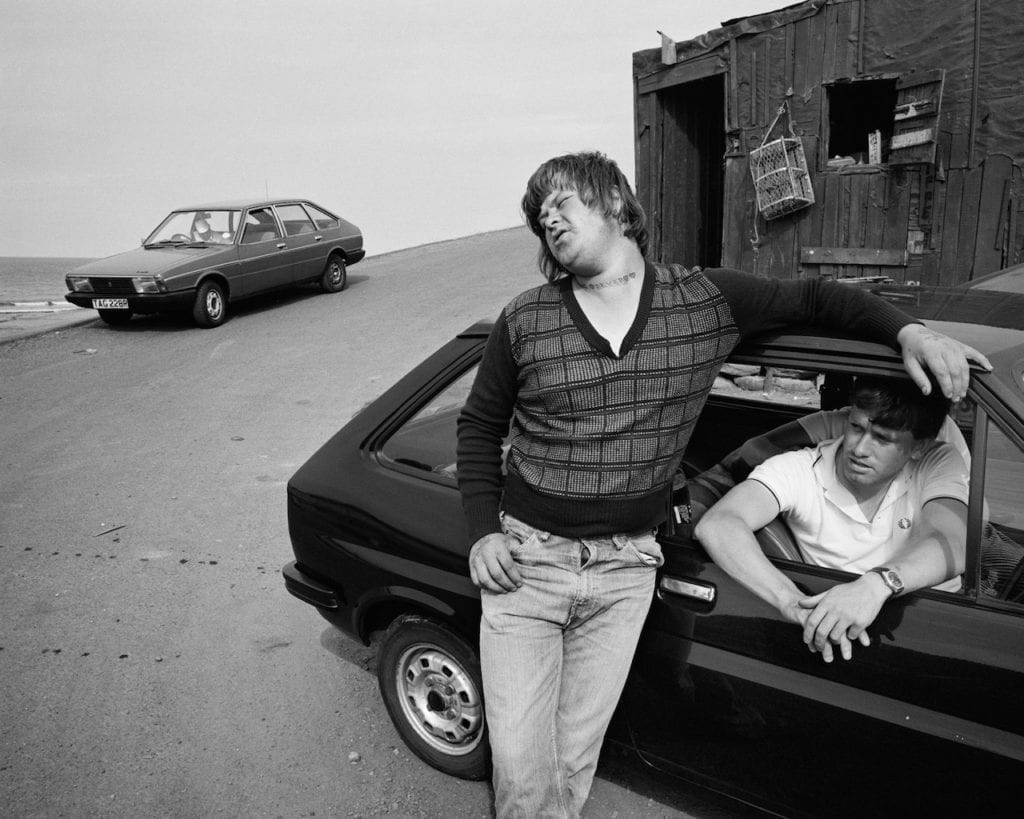

Famously, it took Killip years to get access to the Seacoal beach – the first time he went was in 1976, but he got chased away by the people there. Persisting, he finally got his chance in 1983, and moved into a caravan in the seacoalers’ camp for a year. At the end of the Seacoal book, Killip thanks all the main players in it – Rosie, Brian, Nini, Alison, Helen and Trevor; one of the things he likes about the book, he says, is the fact that the same faces recur. “The same people re-emerge in different situations, you see them eating or laughing or sad or happy,” he explains. “You get a fuller picture, you understand them in a less simplistic way.”

He’s finishing teaching at Harvard at the end of the year, though, and has been working on printing his archive while he still has his studio – he’s made exhibitions from his work on punks and shipbuilding, he says, just to know they’re ready if anyone wants them. I ask if he’d like to start shooting again, and if the increasingly polarised contemporary Britain reminds him of the place he once shot; he says that they’re radically different political moments, as the time and place he photographed recedes into history.

“I don’t think the Left is as strong as it was when I was photographing,” he says. “The weakening of the trade union movements made a big difference in terms of political awareness. When I was photographing in Newcastle there was a lot of political awareness among everyone, and there was a lot of awareness of struggle and strikes and all sorts. The industries were shipbuilding, steel-making and coal mining, and they were enormously influential in terms of people’s political awareness.

“At that time there was the Consett Steel Works, when that closed [in 1980] what replaced it was a crisp factory, and it was women on short term contracts, not working more than 16 hours a week, who became the wage earners. It was completely depoliticised, and that made a big difference to the town. That happened a lot in the industrial North. Things changed.”

Now Then: Chris Killip and the Making of In Flagrante is on view until 13 August at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center. www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/chris_killip/ www.chriskillip.com

Now Then: Chris Killip and the Making of In Flagrante